The Story of the Hero Mak˛ma

(MP3-7,7 MB 16' 04")

Once upon a time, at the town of Senna on the banks of the Zambesi, was born a child. He was not like other children, for he was very tall and strong; over his shoulder he carried a big sack, and in his hand an iron hammer. He could also speak like a grown man, but usually he was very silent.

One day his mother said to him: 'My child, by what name shall we know you?'

And he answered: 'Call all the head men of Senna here to the river's bank.' And his mother called the head men of the town, and when they had come he led them down to a deep black pool in the river where all the fierce crocodiles lived.

'O great men!' he said, while they all listened, 'which of you will leap into the pool and overcome the crocodiles?' But no one would come forward. So he turned and sprang into the water and disappeared.

The people held their breath, for they thought: 'Surely the boy is bewitched and throws away his life, for the crocodiles will eat him!' Then suddenly the ground trembled, and the pool, heaving and swirling, became red with blood, and presently the boy rising to the surface swam on shore.

But he was no longer just a boy! He was stronger than any man and very tall and handsome, so that the people shouted with gladness when they saw him.

'Now, O my people!' he cried, waving his hand, 'you know my nameŚI am Mak˛ma, "the Greater"; for have I not slain the crocodiles into the pool where none would venture?'

Then he said to his mother: 'Rest gently, my mother, for I go to make a home for myself and become a hero.' Then, entering his hut he took Nu-Úndo, his iron hammer, and throwing the sack over his shoulder, he went away.

Mak˛ma crossed the Zambesi, and for many moons he wandered towards the north and west until he came to a very hilly country where, one day, he met a huge giant making mountains.

'Greeting,' shouted Mak˛ma, 'you are you?'

'I am Chi-Úswa-mapýri, who makes the mountains,' answered the giant; 'and who are you?'

'I am Mak˛ma, which signifies "greater,"' answered he.

'Greater than who?' asked the giant.

'Greater than you!' answered Mak˛ma.

The giant gave a roar and rushed upon him. Mak˛ma said nothing, but swinging his great hammer, Nu-Úndo, he struck the giant upon the head.

He struck him so hard a blow that the giant shrank into quite a little man, who fell upon his knees saying: 'You are indeed greater than I, O Mak˛ma; take me with you to be your slave!' So Mak˛ma picked him up and dropped him into the sack that he carried upon his back.

He was greater than ever now, for all the giant's strength had gone into him; and he resumed his journey, carrying his burden with as little difficulty as an eagle might carry a hare.

Before long he came to a country broken up with huge stones and immense clods of earth. Looking over one of the heaps he saw a giant wrapped in dust dragging out the very earth and hurling it in handfuls on either side of him.

'Who are you,' cried Mak˛ma, 'that pulls up the earth in this way?'

'I am Chi-d¨bula-tÓka,' said he, 'and I am making the river-beds.'

'Do you know who I am?' said Mak˛ma. 'I am he that is called "greater"!'

'Greater than who?' thundered the giant.

'Greater than you!' answered Mak˛ma.

With a shout, Chi-d¨bula-tÓka seized a great clod of earth and launched it at Mak˛ma. But the hero had his sack held over his left arm and the stones and earth fell harmlessly upon it, and, tightly gripping his iron hammer, he rushed in and struck the giant to the ground. Chi-d¨bula-tÓka grovelled before him, all the while growing smaller and smaller; and when he had become a convenient size Mak˛ma picked him up and put him into the sack beside Chi-Úswa-mapýri.

He went on his way even greater than before, as all the river-maker's power had become his; and at last he came to a forest of bao-babs and thorn trees. He was astonished at their size, for every one was full grown and larger than any trees he had ever seen, and close by he saw Chi-gwýsa-mýti, the giant who was planting the forest.

Chi-gwýsa-mýti was taller than either of his brothers, but Mak˛ma was not afraid, and called out to him: 'Who are you, O Big One?'

'I,' said the giant, 'am Chi-gwýsa-mýti, and I am planting these bao-babs and thorns as food for my children the elephants.'

'Leave off!' shouted the hero, 'for I am Mak˛ma, and would like to exchange a blow with thee!'

The giant, plucking up a monster bao-bab by the roots, struck heavily at Mak˛ma; but the hero sprang aside, and as the weapon sank deep into the soft earth, whirled Nu-Úndo the hammer round his head and felled the giant with one blow.

So terrible was the stroke that Chi-gwýsa-mýti shrivelled up as the other giants had done; and when he had got back his breath he begged Mak˛ma to take him as his servant. 'For,' said he, 'it is honourable to serve a man so great as thou.'

Mak˛ma, after placing him in his sack, proceeded upon his journey, and travelling for many days he at last reached a country so barren and rocky that not a single living thing grew upon itŚeverywhere reigned grim desolation. And in the midst of this dead region he found a man eating fire.

'What are you doing?' demanded Mak˛ma.

'I am eating fire,' answered the man, laughing; 'and my name is Chi-ýdea-m˛to, for I am the flame-spirit, and can waste and destroy what I like.'

'You are wrong,' said Mak˛ma; 'for I am Mak˛ma, who is "greater" than youŚand you cannot destroy me!'

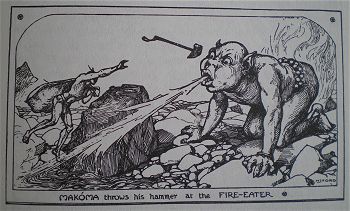

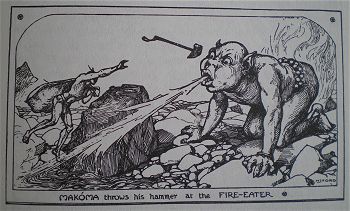

The fire-eater laughed again, and blew a flame at Mak˛ma. But the hero sprang behind a rockŚjust in time, for the ground upon which he had been standing was turned to molten glass, like an overbaked pot, by the heat of the flame-spirit's breath.

Then the hero flung his iron hammer at Chi-ýdea-m˛to, and, striking him, it knocked him helpless; so Mak˛ma placed him in the sack, Woro-n˛wu, with the other great men that he had overcome.

And now, truly, Mak˛ma was a very great hero; for he had the strength to make hills, the industry to lead rivers over dry wastes, foresight and wisdom in planting trees, and the power of producing fire when he wished.

Wandering on he arrived one day at a great plain, well watered and full of game; and in the very middle of it, close to a large river, was a grassy spot, very pleasant to make a home upon.

Mak˛ma was so delighted with the little meadow that he sat down under a large tree and removing the sack from his shoulder, took out all the giants and set them before him. 'My friends,' said he, 'I have travelled far and am weary. Is not this such a place as would suit a hero for his home? Let us then go, to-morrow, to bring in timber to make a kraal.'

So the next day Mak˛ma and the giants set out to get poles to build the kraal, leaving only Chi-Úswa-mapýri to look after the place and cook some venison which they had killed.

In the evening, when they returned, they found the giant helpless and tied to a tree by one enormous hair!

'How is it,' said Mak˛ma, astonished, 'that we find you thus bound and helpless?'

'O Chief,' answered Chi-Úswa-mapýri, 'at mid-day a man came out of the river; he was of immense stature, and his grey moustaches were of such length that I could not see where they ended! He demanded of me "Who is thy master?" And I answered: "Mak˛ma, the greatest of heroes." Then the man seized me, and pulling a hair from his moustache, tied me to this treeŚeven as you see me.'

Mak˛ma was very wroth, but he said nothing, and drawing his finger-nail across the hair (which was as thick and strong as palm rope) cut it, and set free the mountain-maker. The three following days exactly the same thing happened, only each time with a different one of the party; and on the fourth day Mak˛ma stayed in camp when the others went to cut poles, saying that he would see for himself what sort of man this was that lived in the river and whose moustaches were so long that they extended beyond men's sight.

So when the giants had gone he swept and tidied the camp and put some venison on the fire to roast. At midday, when the sun was right overhead, he heard a rumbling noise from the river, and looking up he saw the head and shoulders of an enormous man emerging from it. And behold! right down the river-bed and up the river-bed, till they faded into the blue distance, stretched the giant's grey moustaches!

'Who are you?' bellowed the giant, as soon as he was out of the water.

'I am he that is called Mak˛ma,' answered the hero; 'and, before I slay thee, tell me also what is thy name and what thou doest in the river?'

'My name is Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri,' said the giant. 'My home is in the river, for my moustache is the grey fever-mist that hangs above the water, and with which I bind all those that come unto me so that they die.'

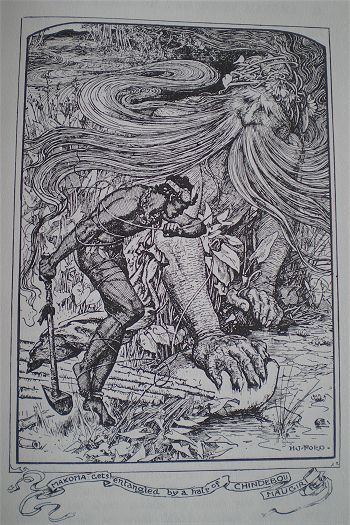

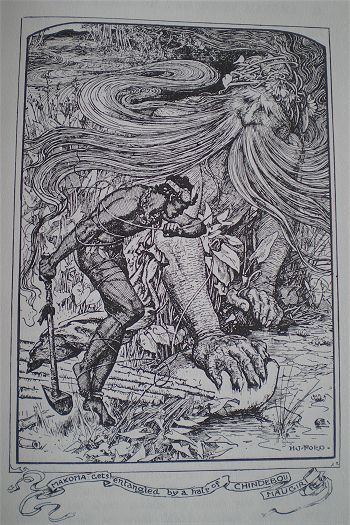

'You cannot bind me!' shouted Mak˛ma, rushing upon him and striking with his hammer. But the river giant was so slimy that the blow slid harmlessly off his green chest, and as Mak˛ma stumbled and tried to regain his balance, the giant swung one of his long hairs around him and tripped him up.

For a moment Mak˛ma was helpless, but remembering the power of the flame-spirit which had entered into him, he breathed a fiery breath upon the giant's hair and cut himself free.

As Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri leaned forward to seize him the hero flung his sack Woron˛wu over the giant's slippery head, and gripping his iron hammer, struck him again; this time the blow alighted upon the dry sack and Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri fell dead.

When the four giants returned at sunset with the poles, they rejoiced to find that Mak˛ma had overcome the fever-spirit, and they feasted on the roast venison till far into the night; but in the morning, when they awoke, Mak˛ma was already warming his hands to the fire, and his face was gloomy.

'In the darkness of the night, O my friends,' he said presently, 'the white spirits of my fathers came upon me and spoke, saying: "Get thee hence, Mak˛ma, for thou shalt have no rest until thou hast found and fought with SÓkatirýna, who had five heads, and is very great and strong; so take leave of thy friends, for thou must go alone."'

Then the giants were very sad, and bewailed the loss of their hero; but Mak˛ma comforted them, and gave back to each the gifts he had taken from them. Then bidding them 'Farewell,' he went on his way.

Mak˛ma travelled far towards the west; over rough mountains and water-logged morasses, fording deep rivers, and tramping for days across dry deserts where most men would have died, until at length he arrived at a hut standing near some large peaks, and inside the hut were two beautiful women.

'Greeting!' said the hero. 'Is this the country of SÓkatirýna of five heads, whom I am seeking?'

'We greet you, O Great One!' answered the women. 'We are the wives of SÓkatirýna; your search is at an end, for there stands he whom you seek!' And they pointed to what Mak˛ma had thought were two tall mountain peaks. 'Those are his legs,' they said; 'his body you cannot see, for it is hidden in the clouds.'

Mak˛ma was astonished when he beheld how tall was the giant; but, nothing daunted, he went forward until he reached one of SÓkatirýna's legs, which he struck heavily with Nu-Úndo. Nothing happened, so he hit again and then again until, presently, he heard a tired, far-away voice saying: 'Who is it that scratches my feet?'

And Mak˛ma shouted as loud as he could, answering: 'It is I, Mak˛ma, who is called "Greater"!' And he listened, but there was no answer.

Then Mak˛ma collected all the dead brushwood and trees that he could find, and making an enormous pile round the giant's legs, set a light to it.

This time the giant spoke; his voice was very terrible, for it was the rumble of thunder in the clouds. 'Who is it,' he said, 'making that fire smoulder around my feet?'

'It is I, Mak˛ma!' shouted the hero. 'And I have come from far away to see thee, O SÓkatirýna, for the spirits of my fathers bade me go seek and fight with thee, lest I should grow fat, and weary of myself.'

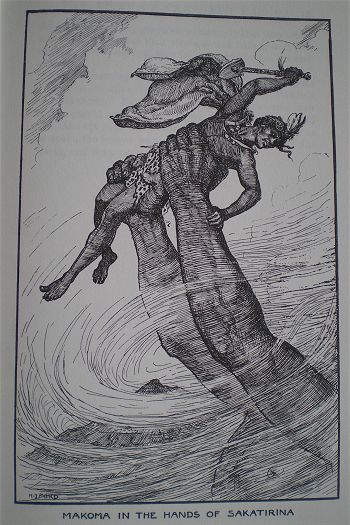

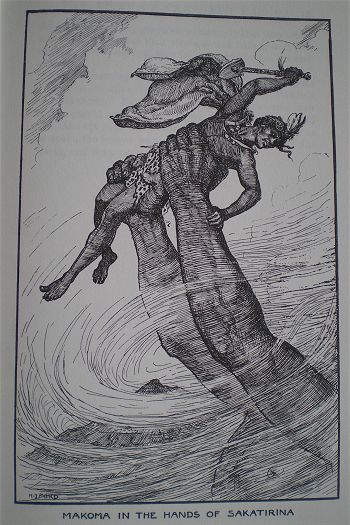

There was silence for a while, and then the giant spoke softly: 'It is good, O Mak˛ma!' he said. 'For I too have grown weary. There is no man so great as I, therefore I am all alone. Guard thyself!' and bending suddenly he seized the hero in his hands and dashed him upon the ground. And lo! instead of death, Mak˛ma had found life, for he sprang to his feet mightier in strength and stature than before, and rushing in he gripped the giant by the waist and wrestled with him.

Hour by hour they fought, and mountains rolled beneath their feet like pebbles in a flood; now Mak˛ma would break away, and summoning up his strength, strike the giant with Nu-Úndo his iron hammer, and SÓkatirýna would pluck up the mountains and hurl them upon the hero, but neither one could slay the other. At last, upon the second day, they grappled so strongly that they could not break away; but their strength was failing, and, just as the sun was sinking, they fell together to the ground, insensible.

In the morning when they awoke, Mulýmo the Great Spirit was standing by them; and he said: 'O Mak˛ma and SÓkatirýna! Ye are heroes so great that no man may come against you. Therefore ye will leave the world and take up your home with me in the clouds.' And as he spake the heroes became invisible to the people of the Earth, and were no more seen among them.

From the Senna (Oral Tradition)

La storia dell'eroe Mak˛ma

Una volta, nella cittÓ di Senna sulle rive dello Zambesi, nacque un bambino. Non era come tutti gli altri, perchÚ era molto alto e forte; portava sulle spalle un grosso sacco e teneva in mano un martello di ferro. Parlava anche come un adulto, ma di solito era molto silenzioso.

Un giorno sua madre gli disse: "Figlio mio, come dovremo chiamarti?"

E lui rispose: "Raduna tutti i capi di Senna qui in riva al fiume." Sua madre chiam˛ tutti i capi della cittÓ e quando furono venuti, egli li condusse a una profonda pozza nera nel fiume dove vivevano tutti i feroci coccodrilli.

"O grandi uomini!" disse, mentre tutti lo ascoltavano, "Chi di voi salterÓ nella pozza e sconfiggerÓ i coccodrilli?" Ma nessuno si fece avanti. Cosý egli si gir˛, balz˛ nell'acqua e sparý.

La gente trattenne il respiro, pensando: "Sicuramente quel bambino Ŕ stregato e getta via la propria vita, perchÚ i coccodrilli lo divoreranno!" All'improvviso la terra trem˛ e la pozza, ribollendo e vorticando, divenne rossa di sangue e subito dopo il bambino, risalendo in superficie, nuot˛ a riva.

Ma non era pi¨ un bambino! Era pi¨ forte di qualsiasi altro uomo, molto alto e affascinante, tanto che la gente grid˛ di contentezza quando lo vide.

"Ora, gente mia!" grid˛, salutando", saprete il mio nome - Non sono io Mak˛ma, «il pi¨ Grande» perchÚ ho ucciso i coccodrilli nella pozza come nessun altro ha osato?''

Allora disse a sua madre: "Riposa dolcemente, madre mia, perchÚ vado a costruirmi una casa e a diventare un eroe." Poi, entrando nel capanno, prese Nu-Úndo, il suo martello di ferro, e gettandosi il sacco sulla spalla, se ne and˛.

Mak˛ma attravers˛ lo Zambesi, e per molte lune vagabond˛ verso nord-est finchÚ giunse in un paese assai collinoso nel quale, un giorno, incontr˛ un enorme gigante che costruiva montagne.

"Salute a te", grid˛ Mak˛ma, "chi sei?"

"Sono Chi-Úswa-mapýri, colui che fa le montagne,'"rispose il gigante, "tu chi sei?"

"Sono Mak˛ma, che significa «il pi¨ grande»" gli rispose.

"Pi¨ grande di chi?" chiese il gigante.

"Pi¨ grande di te!" rispose Mak˛ma.

Il gigante ruggý e si lanci˛ su di lui. Mak˛ma non disse nulla, ma afferrando il suo grande martello, Nu-Úndo, colpý il gigante sulla testa.

Lo colpý tanto duramente che il gigante si ridusse a un ometto, che cadde sulle ginocchia, gridando:"Sei davvero pi¨ grande di me, o Mak˛ma; prendimi con te come schiavo!" cosý Mak˛ma lo raccolse e lo lasci˛ cadere nel sacco che portava sul dorso.

Adesso era ancora pi¨ grande, perchÚ la forza del gigante era confluita in lui; riprese il viaggio, portando il suo carico con il medesimo sforzo di un'aquila che portasse una lepre.

Dopo un po' arriv˛ in un paese smembrato da gigantesche pietre e immensi blocchi di terra. Guardando oltre un mucchio, vide un gigante avvolto dalla polvere che stava trascinando la terra e la stava scagliando a manciate su ciascun fianco.

"Chi sei tu," grid˛ Mak˛ma, "che sollevi la terra in questo modo?"

"Sono Chi-d¨bula-tÓka," disse, "e sto scavando il letto del fiume."

"Sai chi sono?" disse Mak˛ma. " Sono colui che Ŕ chiamato «il pi¨ grande»"

"Pi¨ grande di chi?" tuon˛ il gigante.

"Pi¨ grande di te!" rispose Mak˛ma.

Con un urlo, Chi-d¨bula-tÓka afferr˛ un grande blocco di terra e lo lanci˛ contro Mak˛ma. Ma l'eroe tenne il sacco con il braccio sinistro e le pietre e la terra vi caddero senza danno, poi, afferrando saldamente il suo martello di ferro, corse e stese il gigante al suolo. Chi-d¨bula-tÓka si prostr˛ davanti a lui, diventando all'improvviso sempre pi¨ piccolo, e quando fu della giusta misura, Mak˛ma lo raccolse e lo gett˛ nel sacco accanto a Chi-Úswa-mapýri.

Proseguý per la sua strada pi¨ grande di prima, come se tutto il potere del creatore del fiume fosse confluito in lui; infine giunse in una foresta di baobab e acacie. Rimase sbalordito dalle loro dimensioni, perchÚ ognuno era pi¨ altro e pi¨ grande di qualsiasi albero avesse mai visto, e nelle vicinanze scorse Chi-gwýsa-mýti, il gigante che stava piantando la foresta.

Chi-gwýsa-mýti era il pi¨ alto dei suoi fratelli, ma Mak˛ma non aveva paura e gli chiese:" Chi sei, grand'uomo?"

"Sono Chi-gwýsa-mýti," disse il gigante "e sto piantando questi baobab e acacie come cibo per gli elefanti miei figli."

"Smettila!" grid˛ l'eroe" "perchÚ io sono Mak˛ma e vorrei fare a botte con te!"

Il gigante, strappando un gigantesco baobab con le radici, colpý duramente Mak˛ma, ma l'eroe scatt˛ di lato e, appena l'arma affond˛ nella terra, rote˛ il martello Nu-Úndo intornoa alla testa e abbattÚ il gigante con un sol colpo.

Il colpo fu tanto terribile che Chi-gwýsa-mýti rimpicciolý come gli altri giganti; quando riprese fiato, preg˛ Mak˛ma di prenderlo come suo servo. "PerchÚ Ŕ un onore" disse, "servire un grand'uomo pari tuo."

Dopo averlo infilato nel sacco, Mak˛ma preseguý il proprio viaggio e, viaggiando per vari giorni, infine arriv˛ in un paese cosý arido e roccioso che non vi cresceva nulla - ovunque regnava una cupa desolazione. In mezzo a questa regione desolata trov˛ un uomo che stava mangiando il fuoco.

"Che stai facendo?" chiese Mak˛ma.

"Sto mangiando il fuoco," rispose l'uomo, ridendo, "e mi chiamo Chi-ýdea-m˛to perchÚ sono lo spirito della fiamma e posso devastare e distruggere quel che voglio."

"Ti sbagli," disse Mak˛ma, "perchÚ io sono Mak˛ma, colui che Ŕ pi¨ grande di te-e tu non puoi distruggermi!"

Il mangia-fuoco rise di nuovo e soffi˛ una fiamma contro Mak˛ma. L'eroe balz˛ dietro una roccia-appena in tempo, perchÚ il suolo sul quale stava fu trasformato in vetro fuso, come un vaso surriscaldato, dal calore del fiato dello spirito del fuoco.

Allora l'eroe scagli˛ il suo martello di ferro contro Chi-ýdea-m˛to e, colpendolo, lo lasci˛ inerme; cosý Mak˛ma lo infil˛ nel sacco, Woro-n˛wu, con gli altri grandi uomini che aveva sopraffatto.

E adesso Mak˛ma era davvero un grande eroe, perchÚ aveva la forza di erigere colline, la capacitÓ di far scorrere fiumi in terre aride, la lungimiranza e la saggezza per piantare alberi e il potere di generare fuoco quando volesse.

Girovagando, arriv˛ un giorno in una grande pianura, irrigata e piena di selvaggina,in mezzo alla quale, vicino a un ampio fiume, c'era uno spiazzo erboso, davvero gradevole per costruirvi casa.

Mak˛ma fu cosý contento di quel prato che sedette sotto un grande albero e, togliendo il sacco dalle spalle, tir˛ fuori tutti i giganti e li pose davanti a sÚ. "Amici miei," disse, "ho viaggiato molto e sono stanco. Non Ŕ forse questo il posto pi¨ adatto in cui un eroe possa costruirsi la casa? Domani allora andremo a cercare legna per costruire un kraal" (1)

Cosý il giorno seguente Mak˛ma e i giganti si misero in cammino per prendere pali con i quali costruire il kraal, lasciando solo Chi-Úswa-mapýri a fare la guardia e a cucinare alcuni cervi che avevano ucciso il giorno prima.

La sera, quando tornarono, trovarono il gigante inerme e legato a un albero da un enorme capello!

"Come mai," disse Mak˛ma, sbalordito, "ti troviamo legato e inerme?"

"Padrone," rispose Chi-Úswa-mapýri, "a mezzogiorno Ŕ venuto dal fiume un uomo; era altissimo e aveva certi baffi grigi che non riuscivo a vedere dove finissero! Mi ha chiesto:"Chi Ŕ il tuo signore?" io ho risposto:"Mak˛ma, il pi¨ grande degli eroi." Allora l'uomo mi ha afferrato e prendendo uno dei peli dai suoi baffi, mi ha legato all'albero-cosý come mi hai visto."

Mak˛ma era davvero furioso, ma non disse nulla e passando le unghie sul capello (che era spesso e forte come una corda di fibre di palma) lo tagli˛ e liber˛ il costruttore di montagne. I tre giorni successivi accadde esattamente la stessa cosa, solo che ogni volta si trattava di uno diverso della compagnia; il quarto giorno Mak˛ma rimase all'accampamento mentre gli altri andavano a tagliare i pali, dicendo di voler vedere con i propri occhi che razza di uomo fosse quello che viveva nel fiume e i cui baffi fossero tanto lunghi da estendersi a perdita d'occhio.

Cosý quando i giganti se ne furono andati, egli spazz˛ e riordin˛ l'accampamento e mise ad arrostire alcuni cervi. A mezzogiorno, quando il sole era proprio a picco, udý un rimbombo provenire dal fiume, guard˛ e vide emergere la testa e le spalle di un uomo enorme. E, guarda un po'! su e gi¨ per il fiume, fino a scomparire in lontananza, si stendevano i baffi grigi del gigante!

"Chi sei?" url˛ il gigante, appena fu uscito dall'acqua.

"Sono colui che Ŕ chiamato Mak˛ma," rispose l'eroe, " e prima di ammazzarti, dimmi il tuo nome e che cosa fai nel fiume."

"Mi chiamo Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri," disse il gigante, "Abito nel fiume perchÚ i miei baffi sono la grigia foschia che incombe sull'acqua, con la quale avvinco tutti coloro che vengono a me fino a farli morire."

"Non legherai me!" grid˛ Mak˛ma, lanciandosi su di lui e colpendolo con il martello. Il gigante del fiume era cosý sfuggente che il colpo scivol˛ senza danno sul suo petto verde e come Mak˛ma vacill˛ e cerc˛ di recuperare l'equilibrio, il gigante lo avvolse con uno dei suoi lunghi capelli e lo fece inciampare.

Per un attimo Mak˛ma fu impotente, ma ricordandosi che il potere del fuoco era in lui, soffi˛ un respiro infuocato sui capelli del gigante e si liber˛.

Appena Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri si sporse in avanti per colpirlo, l'eroe scagli˛ il sacco Woron˛wu sulla testa scivolosa del gigante e, brandendo il martello di ferro, lo colpý di nuovo; stavolta il colpo fece presa sul sacco e Chin-dÚbou MÓu-giri cadde morto.

Quando i quattro giganti tornarono al tramonto con i pali, furono lieti di scoprire che Mak˛ma aveva sconfitto lo spirito e banchettarono con i cervi arrostiti fino a notte fonda; il mattino, quando si svegliarono, Mak˛ma si stava giÓ riscaldando le mani al fuoco e il suo viso era cupo.

"Amici miei, nel cuore della notte," disse subito, "i bianchi spiriti dei miei padri sono venuti a me e mi hanno parlato, dicendo:«Procedi dunque, Mak˛ma, perchÚ non avrai riposo finchÚ non avrai trovato e combattuto SÓkatirýna, che ha cinque teste ed Ŕ davvero grande e forte; lascia i tuoi amici perchÚ devi andare da solo»"

Allora i giganti si rattristarono e piansero la perdita del loro eroe; ma Mak˛ma li consol˛ e restituý a ciascuno i doni che aveva preso loro. Poi dicendo loro "Addio", and˛ per la propria strada.

Mak˛ma viaggi˛ verso ovest; oltre irregolari montagne e giungle acquitrinose, guadando fiumi profondi e arrancando attraverso aridi deserti nei quali gli uomini migliori avevano trovato la morte, finchÚ arriv˛ a un capanno, che sorgeva presso grandi vette, in cui si trovavano due splendide donne.

"Salute a voi!" disse l'eroe. "╚ questo il paese di SÓkatirýna dalle cinque teste, che io sto cercando?"

"Salute a te, o Grande Uomo!" risposero le donne. "Siamo le mogli di SÓkatirýna; la tua ricerca Ŕ giunta alla conclusione perchÚ qui si trova colui che cerchi!" Indicarono ci˛ che Mak˛ma riteneva fossero le cime di due alte montagne. "Quelle sono le sue gambe," dissero, "non puoi vedere il suo corpo perchÚ Ŕ nascosto dalle nuvole."

Mak˛ma rimase sbalordito quando vide quanto fosse alto il gigante, ma per nulla scoraggiato, and˛ avanti fino a raggiungere una delle gambe di SÓkatirýna, che colpý duramente con Nu-Úndo. Non accadde nulla, cosý colpý di nuovo e ancora finchÚ, poco dopo, sentý una voce stanca e lontana che diceva:"Chi mi graffia i piedi?"

Mak˛ma grid˛ pi¨ forte che potÚ, rispondendo:"Sono io, Mak˛ma detto «il pi¨ Grande»!" e rimase in ascolto, ma non ci fu nessuna risposta.

Allora Mak˛ma raccolse tutti la sterpaglia e gli alberi che potÚ trovare e, facendone un'enorme pira intorno alle gambe del gigante, le dette fuoco.

Stavolta il gigante parl˛, la sua voce era davvero terribile perchÚ sembrava il rombo del tuono fra le nubi. "Chi sta mandando a fuoco lento i miei piedi?" disse.

"Sono io, Mak˛ma!" grid˛ l'eroe. "Sono venuto da molto lontano per vederti, o SÓkatirýna, perchÚ gli spiriti dei miei padri mi hanno ordinato di venire a cercarti e di combattere con te, affinchÚ io non ingrassi e mi stanchi di me stesso."

Per un po' ci fu silenzio, poi il gigante parl˛ sommessamente:"Bene, Mak˛ma!" disse. "perchÚ anch'io sono cresciuto stanco. Non c'Ŕ uomo grande quanto me, quindi sono solo. Stai in guardia!" e, piegandosi improvvisamente, prese tra le mani l'eroe e lo gett˛ sul terreno. Meraviglia! Invece della morte, Makoma trov˛ la vita perchÚ si rimise in piedi pi¨ forte e alto di prima, e avventandoglisi contro, prese il gigante alla vita e lott˛ con lui.

Lottarono di ora in ora e le montagne tremavano sotto i loro piedi come ciottoli nella piena; Mak˛ma avrebbe voluto staccarsi e raccogliendo le forze, colpý il gigante con Nu-Úndo, il suo martello di ferro, e SÓkatirýna avrebbe voluto sradicare le montagne e scagliarle sull'eroe, ma l'uno non riusciva a uccidere l'altro. Infine, il secondo giorno, lottarono cosý duramente da non potersi staccare, ma le loro forze stavano cedendo e, appena il sole fu tramontato, caddero insieme a terra, stremati.

Quando la mattina si svegliarono, Mulýmo il Grande Spirito era presso di loro e disse:"Mak˛ma e SÓkatirýna! Siete eroi tanto grandi che nessun uomo pu˛ vincervi. Quindi abbandonate questo mondo e dimorate con me tra le nubi." E appena ebbe parlato, gli eroi divennero invisibili agli uomini della terra e non furono mai pi¨ visti fra di essi.

(Senna, Rhodesia, tradizione orale)

(1) Villaggio di capanne circondato da un recinto o da uno steccato.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)