How Isuro the Rabbit Tricked Gudu

(MP3-06,0MB;12'34'')

Far away in a hot country, where the forests are very thick and dark, and the rivers very swift and strong, there once lived a strange pair of friends. Now one of the friends was a big white rabbit named Isuro, and the other was a tall baboon called Gudu, and so fond were they of each other that they were seldom seen apart.

One day, when the sun was hotter even than usual, the rabbit awoke from his midday sleep, and saw Gudu the baboon standing beside him. '

Get up,' said Gudu; 'I am going courting, and you must come with me. So put some food in a bag, and sling it round your neck, for we may not be able to find anything to eat for a long while.'

Then the rabbit rubbed his eyes, and gathered a store of fresh green things from under the bushes, and told Gudu that he was ready for the journey.

They went on quite happily for some distance, and at last they came to a river with rocks scattered here and there across the stream.

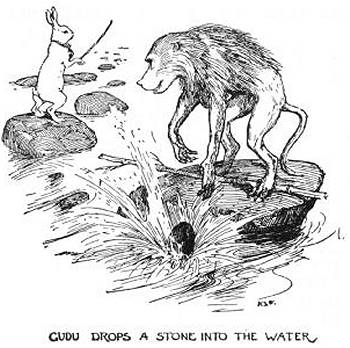

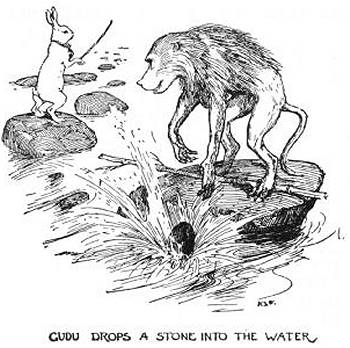

'We can never jump those wide spaces if we are burdened with food,' said Gudu, 'we must throw it into the river, unless we wish to fall in ourselves.' And stooping down, unseen by Isuro, who was in front of him, Gudu picked up a big stone, and threw it into the water with a loud splash.

'It is your turn now,' he cried to Isuro. And with a heavy sigh, the rabbit unfastened his bag of food, which fell into the river.

The road on the other side led down an avenue of trees, and before they had gone very far Gudu opened the bag that lay hidden in the thick hair about his neck, and began to eat some delicious-looking fruit.

'Where did you get that from?' asked Isuro enviously.

'Oh, I found after all that I could get across the rocks quite easily, so it seemed a pity not to keep my bag,' answered Gudu.

'Well, as you tricked me into throwing away mine, you ought to let me share with you,' said Isuro. But Gudu pretended not to hear him, and strode along the path.

By-and-bye they entered a wood, and right in front of them was a tree so laden with fruit that its branches swept the ground. And some of the fruit was still green, and some yellow. The rabbit hopped forward with joy, for he was very hungry; but Gudu said to him: 'Pluck the green fruit, you will find it much the best. I will leave it all for you, as you have had no dinner, and take the yellow for myself.' So the rabbit took one of the green oranges and began to bite it, but its skin was so hard that he could hardly get his teeth through the rind.

'It does not taste at all nice,' he cried, screwing up his face; 'I would rather have one of the yellow ones.'

'No! no! I really could not allow that,' answered Gudu. 'They would only make you ill. Be content with the green fruit.' And as they were all he could get, Isuro was forced to put up with them.

After this had happened two or three times, Isuro at last had his eyes opened, and made up his mind that, whatever Gudu told him, he would do exactly the opposite. However, by this time they had reached the village where dwelt Gudu's future wife, and as they entered Gudu pointed to a clump of bushes, and said to Isuro: 'Whenever I am eating, and you hear me call out that my food has burnt me, run as fast as you can and gather some of those leaves that they may heal my mouth.'

The rabbit would have liked to ask him why he ate food that he knew would burn him, only he was afraid, and just nodded in reply; but when they had gone on a little further, he said to Gudu:

'I have dropped my needle; wait here a moment while I go and fetch it.'

'Be quick then,' answered Gudu, climbing into a tree. And the rabbit hastened back to the bushes, and gathered a quantity of the leaves, which he hid among his fur, 'For,' thought he, 'if I get them now I shall save myself the trouble of a walk by-and-by.'

When he had plucked as many as he wanted he returned to Gudu, and they went on together. The sun was almost setting by the time they reached their journey's end and being very tired they gladly sat down by a well. Then Gudu's betrothed, who had been watching for him, brought out a pitcher of water—which she poured over them to wash off the dust of the road—and two portions of food. But once again the rabbit's hopes were dashed to the ground, for Gudu said hastily:

'The custom of the village forbids you to eat till I have finished.' And Isuro did not know that Gudu was lying, and that he only wanted more food. So he saw hungrily looking on, waiting till his friend had had enough.

In a little while Gudu screamed loudly: 'I am burnt! I am burnt!' though he was not burnt at all. Now, though Isuro had the leaves about him, he did not dare to produce them at the last moment lest the baboon should guess why he had stayed behind. So he just went round a corner for a short time, and then came hopping back in a great hurry. But, quick though he was, Gudu had been quicker still, and nothing remained but some drops of water.

'How unlucky you are,' said Gudu, snatching the leaves; 'no sooner had you gone than ever so many people arrived, and washed their hands, as you see, and ate your portion.' But, though Isuro knew better than to believe him, he said nothing, and went to bed hungrier than he had ever been in his life.

Early next morning they started for another village, and passed on the way a large garden where people were very busy gathering monkey-nuts.

'You can have a good breakfast at last,' said Gudu, pointing to a heap of empty shells; never doubting but that Isuro would meekly take the portion shown him, and leave the real nuts for himself. But what was his surprise when Isuro answered:

'Thank you; I think I should prefer these.' And, turning to the kernels, never stopped as long as there was one left. And the worst of it was that, with so many people about, Gudu could not take the nuts from him.

It was night when they reached the village where dwelt the mother of Gudu's betrothed, who laid meat and millet porridge before them.

'I think you told me you were fond of porridge,' said Gudu; but Isuro answered: 'You are mistaking me for somebody else, as I always eat meat when I can get it.' And again Gudu was forced to be content with the porridge, which he hated.

While he was eating it, however a sudden thought darted into his mind, and he managed to knock over a great pot of water which was hanging in front of the fire, and put it quite out.

'Now,' said the cunning creature to himself, 'I shall be able in the dark to steal his meat!' But the rabbit had grown as cunning as he, and standing in a corner hid the meat behind him, so that the baboon could not find it.

'O Gudu!' he cried, laughing aloud, 'it is you who have taught me to be clever.' And calling to the people of the house, he bade them kindle the fire, for Gudu would sleep by it, but that he would pass the night with some friends in another hut.

It was still quite dark when Isuro heard his name called very softly, and, on opening his eyes, beheld Gudu standing by him. Laying his finger on his nose, in token of silence, he signed to Isuro to get up and follow him, and it was not until they were some distance from the hut that Gudu spoke.

'I am hungry and want something to eat better than that nasty porridge that I had for supper. So I am going to kill one of those goats, and as you are a good cook you must boil the flesh for me.' The rabbit nodded, and Gudu disappeared behind a rock, but soon returned dragging the dead goat with him. The two then set about skinning it, after which they stuffed the skin with dried leaves, so that no one would have guessed it was not alive, and set it up in the middle of a lump of bushes, which kept it firm on its feet. While he was doing this, Isuro collected sticks for a fire, and when it was kindled, Gudu hastened to another hut to steal a pot which he filled with water from the river, and, planting two branches in the ground, they hung the pot with the meat in it over the fire.

'It will not be fit to eat for two hours at least,' said Gudu, 'so we can both have a nap.' And he stretched himself out on the ground, and pretended to fall fast asleep, but, in reality, he was only waiting till it was safe to take all the meat for himself. 'Surely I hear him snore,' he thought; and he stole to the place where Isuro was lying on a pile of wood, but the rabbit's eyes were wide open.

'How tiresome,' muttered Gudu, as he went back to his place; and after waiting a little longer he got up, and peeped again, but still the rabbit's pink eyes stared widely. If Gudu had only known, Isuro was asleep all the time; but this he never guessed, and by-and-bye he grew so tired with watching that he went to sleep himself. Soon after, Isuro woke up, and he too felt hungry, so he crept softly to the pot and ate all the meat, while he tied the bones together and hung them in Gudu's fur. After that he went back to the wood-pile and slept again.

In the morning the mother of Gudu's betrothed came out to milk her goats, and on going to the bushes where the largest one seemed entangled, she found out the trick. She made such lament that the people of the village came running, and Gudu and Isuro jumped up also, and pretended to be as surprised and interested as the rest. But they must have looked guilty after all, for suddenly an old man pointed to them, and cried:

'Those are thieves.' And at the sound of his voice the big Gudu trembled all over.

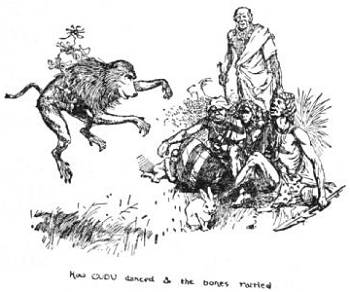

'How dare you say such things? I defy you to prove it,' answered Isuro boldly. And he danced forward, and turned head over heels, and shook himself before them all.

'I spoke hastily; you are innocent,' said the old man; 'but now let the baboon do likewise.' And when Gudu began to jump the goat's bones rattled and the people cried: 'It is Gudu who is the goat-slayer!' But Gudu answered:

'Nay, I did not kill your goat; it was Isuro, and he ate the meat, and hung the bones round my neck. So it is he who should die!' And the people looked at each other, for they knew not what to believe. At length one man said:

'Let them both die, but they may choose their own deaths.'

Then Isuro answered:

'If we must die, put us in the place where the wood is cut, and heap it up all round us, so that we cannot escape, and set fire to the wood; and if one is burned and the other is not, then he that is burned is the goat-slayer.'

And the people did as Isuro had said. But Isuro knew of a hole under the wood-pile, and when the fire was kindled he ran into the hole, but Gudu died there.

When the fire had burned itself out and only ashes were left where the wood had been, Isuro came out of his hole, and said to the people:

'Lo! did I not speak well? He who killed your goat is among those ashes.'

[A Pathan story told to Major Campbell.]

Come il coniglio Isuro ingannò Gudu

C'era una volta lontano lontano, in un caldo paese in cui le foreste sono assai fitte e buie e i fiumi assai rapidi e violenti, una strana coppia di amici. Uno di essi era un grosso coniglio bianco di nome Isuro e l'altro era un babbuino alto di nome Gudu; erano così affezionati l'uno all'altro tanto che raramente li si vedeva separati.

Un giorno, quando il sole era più caldo del solito, il coniglio si svegliò dal sonnellino di mezzogiorno e vide il babbuino Gudu in piedi accanto a sé.

"Su," disse Gudu, "sto andando a fare la corte e tu devi venire con me. Metti un po' di cibo nella borsa e appenditela al collo perché potremmo non trovare niente da mangiare per parecchio."

Allora il coniglio si stropicciò gli occhi e fece provvista di verde cibo fresco sotto i cespugli, poi disse a Gudu di essere pronto per il viaggio.

Procedettero tranquilli per un lungo tratto e alla fine giunsero presso un fiume con le rocce che affioravano qua e là in mezzo alla corrente.

"Non potremo mai saltare questi larghi spazi se saremo carichi di cibo," disse Gudu, "dobbiamo gettarlo nel fiume, se non vogliamo caderci noi stessi." E chinandosi, non visto da Isuro che gli stava davanti, Gudu prese una grossa pietra e la gettò nell'acqua con un gran spruzzo.

"Adesso tocca a te," gridò a Isuro. Con un profondo sospiro il coniglio slacciò la borsa del cibo, che cadde nel fiume.

La strada oltre il fiume procedeva in un largo viale alberato e prima che fossero andati abbastanza lontano, Gudu aprì la borsa che teneva nascosta nel folto pelo del colo e cominciò a mangiare alcuni frutti dall'aspetto delizioso.

"Da dove li hai presi?" chiese Isuro invidioso.

"Oh, ho scoperto che dopotutto avrei potuto oltrepassare le rocce abbastanza facilmente, così mi è sembrato un peccato non tenerli nella borsa." rispose Gudu.

"Ebbene, visto che mi hai ingannato facendomi gettare i miei, dovresti lasciarmi dividerli con te", disse Isuro, ma Gudu fece finta di non sentirlo e s'incammino a grandi passi lungo il sentiero.

Di lì a poco entrarono in un bosco e proprio di fronte a loro c'era un albero così carico di frutta che i rami sfioravano il terreno. Alcuni frutti erano ancora verdi, e altri gialli. Il coniglio saltellò avanti con allegria perché era molto affamato; ma Gudu gli disse: "Cogli i frutti verdi, ti accorgerai che sono i migliori. Li lascerò tutti a te, che non hai cenato, e prenderò per me quelli gialli." Così il coniglio prese una delle arance verdi e cominciò a morderla, ma la buccia era così dura che a malapena riuscì ad affondare i denti nella scorza.

"Non è per niente buona", gridò, facendo una smorfia; "avrei preferito una di quelle gialle."

"No! No! Non posso proprio permetterlo", rispose Gudu. Potrebbero farti ammalare. Accontentati dei frutti verdi." E siccome fu tutto ciò che poté ottenere, Isuro fu obbligato a tenerseli.

Dopo che ciò fu accaduto due o tre volte, Isuro infine aprì gli occhi e capì che, qualunque cosa gli dicesse Gudu, doveva fare esattamente il contrario. In ogni modo, a quel punto avevano raggiunto il villaggio in cui si trovava la futura moglie di Gudu e appena furono entrati, Gudu indicò una macchia di cespugli e disse a Isuro: "Quando sto mangiando e mi senti gridare che il cibo mi ha ustionato, corri più svelto che puoi e raccogli un po' di quelle foglie che possono guarire la mia bocca."

Il coniglio avrebbe voluto chiedergli perché mangiasse cibo che sapeva lo avrebbe bruciato, solo che aveva paura e fece solo un cenno in risposta; ma dopo che ebbero proseguito per un po', disse a Gudu:

"Ho perso il mio ago, aspettami qui un momento mentre vado a prenderlo."

"Allora sbrigati," rispose Gudu, arrampicandosi su un albero. Il coniglio si affrettò a tornare verso i cespugli e raccolse una gran quantità di foglie, che nascose nella pelliccia. "Se le prendo adesso, - pensò - mi risparmio la fatica di un'altra camminata tra poco."

Quando ne ebbe raccolte quante voleva, tornò da Gudu e andarono via insieme. Il sole stava per tramontare quando giunsero alla fine del viaggio e, sentendosi molto stanchi, sedettero volentieri vicino a un pozzo. Allora la fidanzata di Gudu, che era stata attenta a lui, estrasse una brocca d'acqua - che versò su di loro per lavar via la polvere della strada - e due porzioni di cibo. Ancora una volta le speranze del coniglio andarono deluse perché Gudu disse bruscamente:

L'usanza del villaggio ti vieta di mangiare finché io non abbia finito." Isuro non sapeva che Gudu stava mentendo e che voleva solo più cibo. Così lo guardò famelico, aspettando che l'amico ne avesse abbastanza.

Di lì a poco Gudu gridò rumorosamente: "Vado a fuoco! Vado a fuoco!" benché non stesse bruciando proprio per niente. Allora, sebbene Isuro avesse con sé le foglie, non osava estrarle all'ultimo momento, nel timore che il babbuino capisse perche era tornato indietro. Così andò dietro un angolo per un po' di tempo e poi tornò indietro saltellando con gran premura. Ma, per quanto fosse stato veloce, Gudu lo era stato più di lui e non erano rimaste che poche gocce d'acqua.

"Quanto sei sfortunato," disse Gudu, afferrando le foglie; "appena prima che tu tornassi, sé arrivata un po' di gente che si è lavata le mani, come puoi vedere, e ha mangiato la tua porzione." Ma, sebbene Isuro avesse di meglio da fare che credergli, non disse nulla e andò a dormire più affamato di quanto fosse mai stato in vita sua.

Il mattino dopo di buon ora partirono per un altro villaggio e attraversarono un grande giardino nel quale la gente era molto occupata a raccogliere arachidi.

"Alla fine puoi fare un'ottima colazione," disse Gudu, indicando un mucchio di gusci vuoti; non dubitava che Isuro avrebbe preso docilmente la porzione mostratagli, lasciando le vere noccioline a lui. Ma quale fu la sua sorpresa quando Isuro rispose:

"Ti ringrazio; penso di preferire quelle." E dedicandosi ai semi di arachide, non si fermò finché non ne rimase uno. E il peggio era che, con così tanta gente intorno, Gudu non poteva prendere le arachidi per sé.

Era note Quando arrivarono al villaggio in cui viveva la madre della fidanzata di Gudu, che offrì loro carne e porridge (1) di miglio.

"Pensavo mi avessi detto che vai matto per il porridge," disse Gudu; ma Isuro rispose: "Mi stai confondendo con qualcun altro, mangio sempre carne quando ne posso avere." E ancora una volta Gudu fu obbligato ad accontentarsi del porridge, che detestava.

Mentre lo stava mangiando, un pensiero gli attraversò rapido la mente e fece in modo di rovesciare una grande pentola d'acqua appesa davanti al fuoco e di farla uscire tutta.

"Adesso," disse tra sé lo scaltro animale, "sarò in grado di rubargli la carne al buio!" Ma il coniglio si era fatto furbo quanto lui e stava in un angolo nascondendo la carne dietro di sé, così il babbuino non poteva trovarla.

"O Gudu!" gridò, ridendo a voce alta, "sei tu che mi hai insegnato ad essere astuto." E chiamando la gente di casa, chiese loro di accendere il fuoco perché Gudu avrebbe dormito lì, ma lui avrebbe trascorso la notte con un po' di amici in un'altra capanna.

Era piuttosto buio quando Isuro udì chiamare sottovoce il proprio nome e, aprendo gli occhi, vide Gudu che gli stava davanti. Posandogli un dito sul naso, in segno di silenzio, gli fece cenno di alzarsi e di seguirlo e solo quando furono a una certa distanza dalla capanna che Gudu parlò.

"Sono affamato e voglio da mangiare qualcosa di meglio di quel disgustoso porridge che ho per cena. Così vado ad ammazzare qualcuna di quelle capre e siccome tu sei un ottimo cuoco, devi cucinare la carne per me." Il coniglio annuì e Guru scomparve dietro una roccia, ma subito tornò trascinandosi dietro una capra morta. Poi i due cominciarono a scuoiarla, dopodiché riempirono la pelle di foglie secche affinché nessuno si accorgesse che non era viva, poi la misero in mezzo a un gruppo di cespugli che la reggevano dritta sulle zampe. Mentre facevano così, Isuro raccoglieva ramoscelli per il fuoco e quando fu acceso, Gudu corse in un'altra capanna a rubare una pentola, che riempì con l'acqua del fiume; piantando due rami nel terreno, appesero sul fuoco la pentola con la carne.

"Non sarà buona da mangiare per almeno due ore," disse Gudu, "possiamo schiacciare un pisolino tutti e due." E si sdraiò sul terreno, fingendo di addormentarsi subito, ma in realtà stava solo aspettando per essere sicuro di prendere tutta la carne per sé. "Sono certo di sentirlo russare," pensò e si avvicinò furtivo al luogo in cui isuro giaceva su una fascina di legna, la gli occhi del coniglio erano ben aperti.

"Che seccatura," borbottò Gudu mentre tornava al proprio posto e, dopo aver aspettato ancora un po', si alzò e sbirciò di nuovo, ma di nuovo gli occhi rosa del coniglio erano ben spalancati. Se solo Gudu lo avesse saputo, Isuro aveva dormito per tutto il tempo, ma non lo immaginò e di lì a poco fu così stanco di guardare che andò a dormire anche lui. Poco dopo Isuro si svegliò, anche lui era affamato, così raggiunse furtivamente la pentola e mangiò tutta la carne, intanto legò insieme le ossa e le attacco alla pelliccia di Gudu. Dopodiché tornò sulla catasta di legna e si rimise a dormire.

La mattina la madre della fidanzata di Gudu andò a mungere la capra e raggiungendo i cespugli nei quali la più grossa sembrava intrappolata, scoprì l'inganno. Si lamentò tanto che accorse la gente del villaggio e Gudu e Isuro balzarono in piedi anche loro e finsero di essere sorpresi e attenti come gli altri. Ma tutto sommato dovevano avere un'espressione colpevole perché improvvisamente un vecchio li additò e gridò:

"Quei due sono dei ladri." E al suono di quella voce il grosso Gudu tremò tutto.

"Come osi dire ciò? Ti sfido a provarlo," rispose baldanzosamente Isuro. Saltellò insolente, fece una capriola e si scosse davanti a tutti loro.

"Ho parlato avventatamente, sei innocente," disse il vecchio, "ma ora lascia che il babbuino faccia lo stesso." E quando Gudu cominciò a saltare, le ossa della capra sbatacchiarono e la folla gridò: "È Gudu l'assassino della capra!" Gudu rispose:

"No, non ho ucciso io la capra; è stato Isuro e ha mangiato la carne, appendendo poi le ossa la mio collo. È lui che deve morire!" le persone si guardarono le une con le altre perché non sapevano che cosa credere. Infine un uomo disse:

"Lasciamo che muoiano entrambi, ma possano scegliere la loro morte."

Allora Isuro rispose:

"Se dobbiamo morire, allora metteteci dove viene tagliata la legna e accatastatela tutto intorno a noi, così che non possiamo fuggire, poi date fuoco alla legna; se uno di noi è bruciato e l'altro no, allora quello bruciato è l'assassino della capra."

La gente fece come aveva detto Isuro. Ma Isuro sapeva di un buco sotto la catasta di legna e quando il fuoco fu acceso, si gettò nel buco mentre Gudu morì lì.

Quando il fuoco si spense e si trovò solo cenere dove prima vi era la legna, Isuro uscì dal buco e disse alla gente:

"Guardate! Non avevo detto la verità? Chi ha ucciso la capra è tra quelle ceneri."

(1) è un semplice piatto preparato facendo bollire l'aveva nell'acqua o nel latte o in entrambi.

(Una storia dei Pathan, narrata dal maggiore Campbell)

Un esempio di fiaba, contrariamente a quelle di Esopo o di Fedro, in cui gli animali non vengono solo definiti per il loro genere, ma vengono identificati da un nome

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)