Once upon a time there lived, on the bank of a stream, a man and a woman who had a daughter. As she was an only child, and very pretty besides, they never could make up their minds to punish her for her faults or to teach her nice manners; and as for work—she laughed in her mother’s face if she asked her to help cook the dinner or to wash the plates. All the girl would do was to spend her days in dancing and playing with her friends; and for any use she was to her parents they might as well have no daughter at all.

However, one morning her mother looked so tired that even the selfish girl could not help seeing it, and asked if there was anything she was able to do, so that her mother might rest a little.

The good woman looked so surprised and grateful for this offer that the girl felt rather ashamed, and at that moment would have scrubbed down the house if she had been requested; but her mother only begged her to take the fishing-net out to the bank of the river and mend some holes in it, as her father intended to go fishing that night.

The girl took the net and worked so hard that soon there was not a hole to be found. She felt quite pleased with herself, though she had had plenty to amuse her, as everybody who passed by had stopped and had a chat with her. But by this time the sun was high overhead, and she was just folding her net to carry it home again, when she heard a splash behind her, and looking round she saw a big fish jump into the air. Seizing the net with both hands, she flung it into the water where the circles were spreading one behind the other, and, more by luck than skill, drew out the fish.

‘Well, you are a beauty!’ she cried to herself; but the fish looked up to her and said:

‘You had better not kill me, for, if you do, I will turn you into a fish yourself!’

The girl laughed contemptuously, and ran straight in to her mother.

‘Look what I have caught,’ she said gaily; ‘but it is almost a pity to eat it, for it can talk, and it declares that, if I kill it, it will turn me into a fish too.’ ‘Oh, put it back, put it back!’ implored the mother. ‘Perhaps it is skilled in magic. And I should die, and so would your father, if anything should happen to you.’ ‘Oh, nonsense, mother; what power could a creature like that have over me? Besides, I am hungry, and if I don’t have my dinner soon, I shall be cross.’ And off she went to gather some flowers to stick in her hair.

About an hour later the blowing of a horn told her that dinner was ready.

‘Didn’t I say that fish would be delicious?’ she cried; and plunging her spoon into the dish the girl helped herself to a large piece. But the instant it touched her mouth a cold shiver ran through her. Her head seemed to flatten, and her eyes to look oddly round the corners; her legs and her arms were stuck to her sides, and she gasped wildly for breath. With a mighty bound she sprang through the window and fell into the river, where she soon felt better, and was able to swim to the sea, which was close by.

No sooner had she arrived there than the sight of her sad face attracted the notice of some of the other fishes, and they pressed round her, begging her to tell them her story.

‘I am not a fish at all,’ said the new-comer, swallowing a great deal of salt water as she spoke; for you cannot learn how to be a proper fish all in a moment. ‘I am not a fish at all, but a girl; at least I was a girl a few minutes ago, only—’ And she ducked her head under the waves so that they should not see her crying.

‘Only you did not believe that the fish you caught had power to carry out its threat,’ said an old tunny. ‘Well, never mind, that has happened to all of us, and it really is not a bad life. Cheer up and come with us and see our queen, who lives in a palace that is much more beautiful than any your queens can boast of.’

The new fish felt a little afraid of taking such a journey; but as she was still more afraid of being left alone, she waved her tail in token of consent, and off they all set, hundreds of them together. The people on the rocks and in the ships that saw them pass said to each other:

‘Look what a splendid shoal!’ and had no idea that they were hastening to the queen’s palace; but, then, dwellers on land have so little notion of what goes on in the bottom of the sea! Certainly the little new fish had none. She had watched jelly-fish and nautilus swimming a little way below the surface, and beautiful coloured sea-weeds floating about; but that was all. Now, when she plunged deeper her eyes fell upon strange things.

Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl, inestimable stones, unvalued jewels—all scattered in the bottom of the sea! Dead men’s bones were there also, and long white creatures who had never seen the light, for they mostly dwelt in the clefts of rocks where the sun’s rays could not come. At first our little fish felt as if she were blind also, but by-and-by she began to make out one object after another in the green dimness, and by the time she had swum for a few hours all became clear.

‘Here we are at last,’ cried a big fish, going down into a deep valley, for the sea has its mountains and valleys just as much as the land. ‘That is the palace of the queen of the fishes, and I think you must confess that the emperor himself has nothing so fine.’

‘It is beautiful indeed,’ gasped the little fish, who was very tired with trying to swim as fast as the rest, and beautiful beyond words the palace was. The walls were made of pale pink coral, worn smooth by the waters, and round the windows were rows of pearls; the great doors were standing open, and the whole troop floated into the chamber of audience, where the queen, who was half a woman after all, was seated on a throne made of a green and blue shell.

‘Who are you, and where do you come from?’ said she to the little fish, whom the others had pushed in front. And in a low, trembling voice, the visitor told her story.

‘I was once a girl too,’ answered the queen, when the fish had ended; ‘and my father was the king of a great country. A husband was found for me, and on my wedding-day my mother placed her crown on my head and told me that as long as I wore it I should likewise be queen. For many months I was as happy as a girl could be, especially when I had a little son to play with. But, one morning, when I was walking in my gardens, there came a giant and snatched the crown from my head. Holding me fast, he told me that he intended to give the crown to his daughter, and to enchant my husband the prince, so that he should not know the difference between us. Since then she has filled my place and been queen in my stead. As for me, I was so miserable that I threw myself into the sea, and my ladies, who loved me, declared that they would die too; but, instead of dying, some wizard, who pitied my fate, turned us all into fishes, though he allowed me to keep the face and body of a woman. And fished we must remain till someone brings me back my crown again!’

‘I will bring it back if you tell me what to do!’ cried the little fish, who would have promised anything that was likely to carry her up to earth again. And the queen answered:

‘Yes, I will tell you what to do.’

She sat silent for a moment, and then went on:

‘There is no danger if you will only follow my counsel; and first you must return to earth, and go up to the top of a high mountain, where the giant has built his castle. You will find him sitting on the steps weeping for his daughter, who has just died while the prince was away hunting. At the last she sent her father my crown by a faithful servant. But I warn you to be careful, for if he sees you he may kill you. Therefore I will give you the power to change yourself into any creature that may help you best. You have only to strike your forehead, and call out its name.’

This time the journey to land seemed much shorter than before, and when once the fish reached the shore she struck her forehead sharply with her tail, and cried:

‘Deer, come to me!’

In a moment the small, slimy body disappeared, and in its place stood a beautiful beast with branching horns and slender legs, quivering with longing to be gone. Throwing back her head and snuffing the air, she broke into a run, leaping easily over the rivers and walls that stood in her way.

It happened that the king’s son had been hunting since daybreak, but had killed nothing, and when the deer crossed his path as he was resting under a tree he determined to have her. He flung himself on his horse, which went like the wind, and as the prince had often hunted the forest before, and knew all the short cuts, he at last came up with the panting beast.

‘By your favour let me go, and do not kill me,’ said the deer, turning to the prince with tears in her eyes, ‘for I have far to run and much to do.’ And as the prince, struck dumb with surprise, only looked at her, the deer cleared the next wall and was soon out of sight.

‘That can’t really be a deer,’ thought the prince to himself, reining in his horse and not attempting to follow her. ‘No deer ever had eyes like that. It must be an enchanted maiden, and I will marry her and no other.’ So, turning his horse’s head, he rode slowly back to his palace.

The deer reached the giant’s castle quite out of breath, and her heart sank as she gazed at the tall, smooth walls which surrounded it. Then she plucked up courage and cried:

‘Ant, come to me!’ And in a moment the branching horns and beautiful shape had vanished, and a tiny brown ant, invisible to all who did not look closely, was climbing up the walls.

It was wonderful how fast she went, that little creature! The wall must have appeared miles high in comparison with her own body; yet, in less time than would have seemed possible, she was over the top and down in the courtyard on the other side. Here she paused to consider what had best be done next, and looking about her she saw that one of the walls had a tall tree growing by it, and in the corner was a window very nearly on a level with the highest branches of the tree.

‘Monkey, come to me!’ cried the ant; and before you could turn round a monkey was swinging herself from the topmost branches into the room where the giant lay snoring.

‘Perhaps he will be so frightened at the sight of me that he may die of fear, and I shall never get the crown,’ thought the monkey. ‘I had better become something else.’ And she called softly: ‘Parrot, come to me!’

Then a pink and grey parrot hopped up to the giant, who by this time was stretching himself and giving yawns which shook the castle. The parrot waited a little, until he was really awake, and then she said boldly that she had been sent to take away the crown, which was not his any longer, now his daughter the queen was dead.

On hearing these words the giant leapt out of bed with an angry roar, and sprang at the parrot in order to wring her neck with his great hands. But the bird was too quick for him, and, flying behind his back, begged the giant to have patience, as her death would be of no use to him.

‘That is true,’ answered the giant; ‘but I am not so foolish as to give you that crown for nothing. Let me think what I will have in exchange!’ And he scratched his huge head for several minutes, for giants’ minds always move slowly.

‘Ah, yes, that will do!’ exclaimed the giant at last, his face brightening. ‘You shall have the crown if you will bring me a collar of blue stones from the Arch of St. Martin, in the Great City.’

Now when the parrot had been a girl she had often heard of this wonderful arch and the precious stones and marbles that had been let into it. It sounded as if it would be a very hard thing to get them away from the building of which they formed a part, but all had gone well with her so far, and at any rate she could but try. So she bowed to the giant, and made her way back to the window where the giant could not see her. Then she called quickly:

‘Eagle, come to me!’

Before she had even reached the tree she felt herself borne up on strong wings ready to carry her to the clouds if she wished to go there, and seeming a mere speck in the sky, she was swept along till she beheld the Arch of St. Martin far below, with the rays of the sun shining on it. Then she swooped down, and, hiding herself behind a buttress so that she could not be detected from below, she set herself to dig out the nearest blue stones with her beak. It was even harder work than she had expected; but at last it was done, and hope arose in her heart. She next drew out a piece of string that she had found hanging from a tree, and sitting down to rest strung the stones together. When the necklace was finished she hung it round her neck, and called: ‘Parrot, come to me!’ And a little later the pink and grey parrot stood before the giant.

‘Here is the necklace you asked for,’ said the parrot. And the eyes of the giant glistened as he took the heap of blue stones in his hand. But for all that he was not minded to give up the crown.

‘They are hardly as blue as I expected,’ he grumbled, though the parrot knew as well as he did that he was not speaking the truth; ‘so you must bring me something else in exchange for the crown you covet so much. If you fail it will cost you not only the crown but you life also.’

‘What is it you want now?’ asked the parrot; and the giant answered:

‘If I give you my crown I must have another still more beautiful; and this time you shall bring me a crown of stars.’

The parrot turned away, and as soon as she was outside she murmured:

‘Toad, come to me!’ And sure enough a toad she was, and off she set in search of the starry crown.

She had not gone far before she came to a clear pool, in which the stars were reflected so brightly that they looked quite real to touch and handle. Stooping down she filled a bag she was carrying with the shining water and, returning to the castle, wove a crown out of the reflected stars. Then she cried as before:

‘Parrot, come to me!’ And in the shape of a parrot she entered the presence of the giant.

‘Here is the crown you asked for,’ she said; and this time the giant could not help crying out with admiration. He knew he was beaten, and still holding the chaplet of stars, he turned to the girl.

‘Your power is greater than mine: take the crown; you have won it fairly!’

The parrot did not need to be told twice. Seizing the crown, she sprang on to the window, crying: ‘Monkey, come to me!’ And to a monkey, the climb down the tree into the courtyard did not take half a minute. When she had reached the ground she said again: ‘Ant, come to me!’ And a little ant at once began to crawl over the high wall. How glad the ant was to be out of the giant’s castle, holding fast the crown which had shrunk into almost nothing, as she herself had done, but grew quite big again when the ant exclaimed:

‘Deer, come to me!’

Surely no deer ever ran so swiftly as that one! On and on she went, bounding over rivers and crashing through tangles till she reached the sea. Here she cried for the last time:

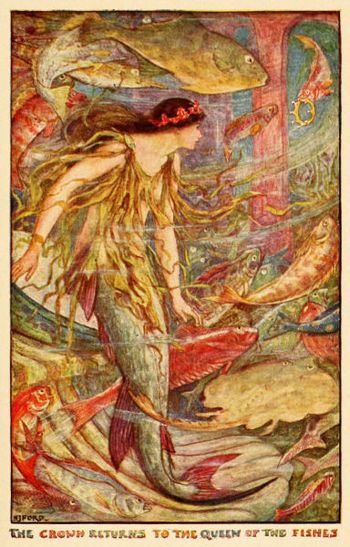

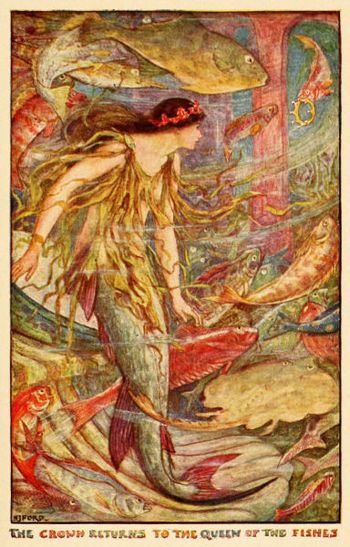

‘Fish, come to me!’ And, plunging in, she swam along the bottom as far as the palace, where the queen and all the fishes gathered together awaiting her.

The hours since she had left had gone very slowly—as they always do to people that are waiting—and many of them had quite given up hope.

‘I am tired of staying here,’ grumbled a beautiful little creature, whose colours changed with every movement of her body, ‘I want to see what is going on in the upper world. It must be months since that fish went away.’

‘It was a very difficult task, and the giant must certainly have killed her or she would have been back long ago,’ remarked another.

‘The young flies will be coming out now,’ murmured a third, ‘and they will all be eaten up by the river fish! It is really too bad!’ When, suddenly, a voice was heard from behind: ‘Look! look! what is that bright thing that is moving so swiftly towards us?’ And the queen started up, and stood on her tail, so excited was she.

A silence fell on all the crowd, and even the grumblers held their peace and gazed like the rest. On and on came the fish, holding the crown tightly in her mouth, and the others moved back to let her pass.

On she went right up to the queen, who bent and, taking the crown, placed it on her own head. Then a wonderful thing happened. Her tail dropped away or, rather, it divided and grew into two legs and a pair of the prettiest feet in the world, while her maidens, who were grouped around her, shed their scales and became girls again. They all turned and looked at each other first, and next at the little fish who had regained her own shape and was more beautiful than any of them.

‘It is you who have given us back our life; you, you!’ they cried; and fell to weeping from very joy.

So they all went back to earth and the queen’s palace, and quite forgot the one that lay under the sea. But they had been so long away that they found many changes. The prince, the queen’s husband, had died some years since, and in his place was her son, who had grown up and was king! Even in his joy at seeing his mother again an air of sadness clung to him, and at last the queen could bear it no longer, and begged him to walk with her in the garden. Seated together in a bower of jessamine—where she had passed long hours as a bride—she took her son’s hand and entreated him to tell her the cause of his sorrow. ‘For,’ said she, ‘if I can give you happiness you shall have it.’

‘It is no use,’ answered the prince; ‘nobody can help me. I must bear it alone.’

‘But at least let me share your grief,’ urged the queen.

‘No one can do that,’ said he. ‘I have fallen in love with what I can never marry, and I must get on as best I can.’

‘It may not be as impossible as you think,’ answered the queen. ‘At any rate, tell me.’

There was silence between them for a moment, then, turning away his head, the prince answered gently:

‘I have fallen in love with a beautiful deer!’

‘Ah, if that is all,’ exclaimed the queen joyfully. And she told him in broken words that, as he had guessed, it was no deer but an enchanted maiden who had won back the crown and brought her home to her own people.

‘She is here, in my palace,’ added the queen. ‘I will take you to her.’

But when the prince stood before the girl, who was so much more beautiful than anything he had ever dreamed of, he lost all his courage, and stood with bent head before her.

Then the maiden drew near, and her eyes, as she looked at him, were the eyes of the deer that day in the forest. She whispered softly:

‘By your favour let me go, and do not kill me.’

And the prince remembered her words, and his heart was filled with happiness. And the queen, his mother, watched them and smiled.

From Cuentos populars catalans, por lo Dr. D. Francisco de S. Maspos y Labros

La ragazza pesce

C’erano una volta un uomo, una donna e la loro figlia che vivevano sulla riva di un fiume. Siccome era la loro unica figlia, e inoltre assai graziosa, non si erano mai preoccupati di castigarla per i suoi errori o di insegnarle le buone maniere; per questo rideva in faccia alla madre quando le chiedeva di aiutarla a cucinare il pranzo o a lavare i piatti. Tutto ciò che la ragazza voleva fare era trascorrere i giorni danzando e giocando con gli amici; e siccome non era di nessuna utilità ai genitori, avrebbero anche potuto non avere per niente una figlia.

Comunque una mattina sua madre era così stanca che persino l’egoista ragazza non poté non notarlo e le chiese se vi fosse qualcosa che lei fosse in grado di fare, così che la madre potesse riposare un po’.

La brava donna fu così sorpresa e contenta per questa offerta che la ragazza si vergognò abbastanza e avrebbe pulito la casa da cima a fondo se glielo avesse chiesto, ma la madre le chiese solo di prendere la rete da pesca sulla riva del fiume e di rammendarne alcuni buchi perché il padre quella notte intendeva andare a pescare.

La ragazza prese la rete e lavorò così intensamente che ben presto non vi fu un solo buco. Si sentiva contenta di se stessa, sebbene si fosse molto divertita perché chiunque passasse si fermava a chiacchierare con lei. A quel punto il sole era alto in cielo e lei stava giusto piegando la rete per portarla di nuovo a casa quando udì un tonfo dietro di sé e, guardandosi attorno, vide un grosso pesce che balzava in aria. Afferrando la rete con entrambe le mani, la gettò nell’acqua dove si stavano allargando i cerchi uno dentro l’altro, e prese il pesce, più per fortuna che per abilità.

‘Sei una bellezza!’ disse a se stessa, ma il pesce guardò in su verso di lei e disse:

“Faresti meglio a non uccidermi perché, se lo farai, ti trasformerò in un pesce!”

La ragazza rise sprezzante e corse da sua madre.

“Guarda che cosa ho catturato,” disse allegramente, “ma è quasi un peccato mangiarlo perché può parlare e ha affermato che, se lo ucciderò, trasformerà anche me in un pesce.”

“Riportalo indietro! Riportalo indietro!” implorò la madre. “Forse è capace di fare incantesimi. E io morirei, e anche tuo padre, se dovesse accaderti qualcosa.”

“Che sciocchezze, mamma; che potere può avere su di me una creatura così? Inoltre ho fame e se non avrò presto la mia cena, sarò di cattivo umore.” E andò a cogliere un po’ di fiori da mettersi nei capelli.

Circa un’ora più tardi il suono di un corno le disse che la cena era pronta.

“Non avevo detto che il pesce sarebbe stato delizioso?” esclamò la ragazza e, infilando il cucchiaio nel piatto, prese una generosa porzione. Ma nell’istante in cui le toccò la bocca, fu percorsa da un brivido gelido. Le sembrò che la testa si appiattisse e gli occhi stranamente si spostassero agli angoli; le gambe e le braccia le si incollarono ai fianchi e sussultò terribilmente per respirare. Con un potente balzo si gettò attraverso la finestra e cadde nel fiume, dove si sentì meglio e fu in grado di nuotare fino al mare, che era vicino.

Appena fu arrivata, la vista della sua espressione triste attirò l’attenzione degli altri pesci e le si fecero attorno, pregandola di raccontar loro la propria storia.

“Io non sono affatto un pesce.” disse la nuova arrivata, ingoiando un gran sorso di acqua salata mentre parlava perché non si può imparare in un momento come essere un vero e proprio pesce. “Io non sono affatto un pesce, ma una ragazza; almeno ero una ragazza fino a pochi minuti fa…” e piegò la testa sotto le onde perché non la vedessero piangere.

“Solo che non credevi il pesce avesse il potere di realizzare la sua minaccia,” disse un vecchio tonno. “Non ti preoccupare, è accaduto a tutti noi e non è davvero una brutta vita. Su con la vita e vieni con noi a vedere la nostra regina, che vive in un palazzo assai più bello di quanto possa vantarsi qualsiasi altra tua regina.”

La nuova pesciolina aveva un po’ paura di intraprendere un viaggio simile, ma siccome avrebbe avuto ancor più paura restando sola, agitò la coda in segno di assenso e andò con loro, che erano a centinaia. Le persone sugli scogli e nelle barche si dissero le une con le altre, vedendoli passare:

“Guarda che splendido banco!” e non avevano idea che si stessero affrettando verso il palazzo della regina perché gli abitanti della terra hanno così poca conoscenza di ciò che accade in fondo al mare! Certamente la pesciolina nuova non ne aveva nessuna. Guardava meduse e molluschi nuotare a pelo d’acqua e meravigliose e variopinte alghe fluttuare lì vicino, ma era tutto. Adesso, quando spingeva più a fondo lo sguardo, vedeva cose strane.

Mucchi d’oro, grandi ancore, cumuli di perle, pietre inestimabili, gioielli di valore incalcolabile… tutto sparpagliato sul fondo del mare! C’erano anche ossa di uomini morti e lunghe creature bianche che non avevano mai visto la luce perché la maggior parte di loro abitava in fenditure in cui non arrivavano mai i raggi del sole. Dapprima la nostra pesciolina si sentiva come fosse cieca, ma pian piano cominciò a mettere a fuoco una cosa dopo l’altra in quell’oscurità verde e dopo che ebbe nuotato per un po’ di ore, tutto divenne chiaro.

“Infine eccoci arrivati.” esclamò un grosso pesce, scendendo in un profondo avvallamento perché il mare ha montagne e valli proprio come la terra. “Questo è il palazzo della regina dei pesci e penso dobbiamo riconoscere che nemmeno l’imperatore in persona ha nulla di così bello.”

“È davvero splendido.” ansimò la pesciolina, che era molto stanca per aver cercato di nuotare veloce come il banco, e bello al di là delle parole era il palazzo. Le mura erano di corallo rosa pallido, levigato dall’acqua, e intorno alle finestre vi erano file di perle; le grandi porte erano aperte e tutto il banco di pesci nuotò nella sala delle udienze in cui la regina, che era per metà donna, era seduta su un trono di conchiglie verdi e blu.

“Chi siete e da dove venite?” chiese alla pesciolina, che gli altri avevano spinto avanti. Con voce bassa e tremante, la visitatrice narrò la propria storia.

“Anche io ero una ragazza,” rispose la regina, quando la pesciolina ebbe terminato di parlare, “e mio padre era il re di un grande paese. Mi era stato trovato un marito e il giorno delle nozze mia madre mi mise in testa la sua corona e mi disse che fino a quando l’avessi indossata, io sarei stata altrettanto regina. Per molti mesi sono stata felice come può esserlo una ragazza, specialmente quando ha un bambino con cui giocare. Ma una mattina, mentre stavo camminando nei giardini, venne un gigante e mi strappò la corona dalla testa. Tenendomi ferma, mi disse che aveva intenzione di dare la corona a sua figlia e di gettare un incantesimo sul principe mio marito così che non potesse vedere la differenza tra di noi. Da allora lei ha preso il mio posto ed è regina al posto mio. Quanto a me, mi sentivo così miserabile che mi sono gettata in mare e le mie dame, che mi amavano, hanno detto che sarebbero morte anche loro; invece di morire, un certo mago, che ha avuto pietà della mia sorte, ci ha trasformate in pesci, sebbene mi abbia concesso di conservare il volto e il corpo di donna. E pesci resteremo finché qualcuno mi porterà di nuovo la mia corona!”

“Ve la riporterò io, se mi direte come fare!” esclamò la pesciolina, che avrebbe promesso qualsiasi cosa che le consentisse di tornare di nuovo sulla terra. E la regina rispose:

“Sì, ti dirò come fare.”

Sedette in silenzio per un momento e poi proseguì:

“Non ci sarà pericolo se seguirai i miei consigli; prima devi tornare sulla terra e salire in cima a un’alta montagna sulla quale il gigante ha costruito il suo castello. Lo troverai seduto sugli scalini che piange per la figlia, che è morta proprio mentre il principe stava andando a caccia. All’ultimo momento lei ha mandato la mia corona al padre per mezzo di un fedele servitore. Ti raccomando di stare attenta perché se ti vede, ti ucciderà. Quindi ti conferirò il potere di trasformarti in qualsiasi creatura ti possa aiutare nel modo migliore. Dovrai solo colpirti la fronte e chiamarla per nome.”

Questa volta il viaggio verso la terra sembrò più breve del precedente e quando il pesce ebbe raggiunto la spiaggia, si colpì decisamente la fronte con la coda e gridò:

“Cerva, vieni a me!”

In un attimo il piccolo corpo viscido sparì e al suo posto comparve uno splendido animale con le corna ramificate e le zampe snelle, che tremavano per il desiderio di muoversi. Gettando indietro la testa e annusando l’aria, si mise a correre, oltrepassando facilmente i fiumi e i muri che incontrava sul suo cammino.

Si dava il caso che il figlio del re stesse cacciando fin dall’alba, ma non aveva ancora ucciso niente e quando la cerva attraversò il suo sentiero, mentre stava riposando sotto un albero, decise di catturarla. Montò sul suo cavallo, che correva come il vento e che come il principe aveva spesso cacciato prima in quella foresta, e conosceva tutte le scorciatoie, e alla fine s’imbatté nella bestia ansimante.

“Per favore, lasciami andare e non uccidermi,” disse la cerva, volgendosi al principe con le lacrime agli occhi “perché devo correre lontano e ho molto da fare.” E siccome il principe, impietrito per la sorpresa, la guardava e basta, la cerva saltò il muro successivo e sparì alla sua vista.

‘Non può essere davvero una cerva’ pensava il principe, trattenendo il cavallo e non azzardandosi a seguirla. ‘Nessuna cerva ha occhi simili. Deve essere una fanciulla sotto incantesimo e io sposerò lei o nessun’altra.’ Così, voltando la testa del cavallo, cavalcò lentamente verso il palazzo.

La cerva raggiunse il castello del gigante quasi senza fiato e il cuore le sobbalzò quando vide da quali mura alte e lisce era circondato. Si fece coraggio ed esclamò:

“Formica, vieni a me!” e in un attimo le corna ramificate e il bellissimo aspetto svanirono e una piccola formica bruna, invisibile a chiunque non guardasse da vicino, cominciò ad arrampicarsi sul muro.

Era meraviglioso quanto andasse veloce, quella piccolo creatura! Il muro doveva apparire alto per miglia rispetto al suo corpo tuttavia, in meno tempo di quanto sembrasse possibile, lei fu in cima e poi giù nel cortile dall’altra parte. Lì si fermò a considerare che cosa sarebbe stato meglio fare dopo e, guardandosi attorno, vide che uno dei muri aveva un alto albero che gli cresceva vicino e che sull’angolo vi era una finestra proprio al livello dei rami più alti dell’albero.

“Scimmia, vieni a me!” gridò la formica; prima che voi poteste girarvi, c’era una scimmia che dai rami più alti si dondolava fin dentro la stanza in cui il gigante stava russando.

‘Forse potrebbe spaventarsi tanto alla mia vista da morire di paura e io potrei prendere la corona.’ pensò la scimmia ‘Sarà meglio che mi trasformi in qualcos’altro.’ E disse sottovoce: “Pappagallo, vieni a me!”

Allora un pappagallo rosa e grigio saltellò sul gigante, che nel frattempo si stava stirando e sbadigliava da far tremare il castello. Il pappagallo attese un po’, finché fu davvero sveglio, poi gli disse audacemente che era stato mandato a portar via la corona, che non gli apparteneva più dal momento che la figlia la regina era morta.

Nell’udire queste parole il gigante balzò dal letto con un urlo di rabbia e si gettò sul pappagallo per strozzarlo con le sue grandi mani. Ma l’uccello era troppo veloce per lui e, volandogli dietro la schiena, chiese al gigante di avere pazienza perché la sua morte non gli sarebbe stata utile.

“È vero,” disse il gigante “ma non sono così pazzo da darti la corona per niente. Lasciami pensare che cosa potrei chiederti in cambio!” e si grattò la grossa testa per qualche minuto perché la mente dei giganti funziona sempre lentamente.

“Sì, ho trovato!” esclamò infine il gigante, con il viso illuminato. “Avrai la corona se mi porterai un collare di pietre blu dall’arco di san Martino, nella Grande Città.

Quando il pappagallo era ancora una fanciulla, aveva spesso sentito di questo meraviglioso arco e delle pietre preziose e del marmo che lo costituivano. Sembrava una cosa davvero difficile portarle via dalla costruzione di cui facevano parte, ma tutto le era andato ben sin dal principio e in ogni modo avrebbe tentato. Così s’inchinò al gigante e tornò alla finestra dove non poteva vederla. Poi disse in fretta:

“Aquila, vieni a me!”

Prima ancora di aver raggiunto l’albero, si ritrovò dotata di forti ali che potevano portarla fino alle nuvole, se avesse desiderato andare là e, simile a un semplice granello in cielo, volò velocemente finché vide l’arco di san Martino giù in lontananza, con i raggi del sole che vi scintillavano. Allora scese in picchiata e, nascondendosi dietro un contrafforte, così che non la si potesse scorgere dal basso, si mise a scalzare con il becco la pietra blu più vicina. Il lavoro era più duro di quanto si fosse aspettata, ma alla fine fu fatto e in cuore le rinacque la speranza. Poi tirò fuori un pezzo di spago che aveva visto pendere da un albero e, sedendo a riposare, infilò le pietre. Quando la collana fu terminata, se l’appese al collo e chiamò: “Pappagallo, vieni a me!” E poco dopo il pappagallo rosa e grigio era davanti al gigante.

“Ecco la collana che hai chiesto.” disse il pappagallo. Gli occhi del gigante brillarono mentre prendeva in mano il mucchio di pietre blu, ma dopo tutto non aveva intenzione di privarsi della corona.

“Sono a malapena del blu che mi aspettavo,” brontolò, sebbene il pappagallo sapesse bene che non stava dicendo la verità. “così dovrai portarmi qualcos’altro in cambio della corona che desideri tanto. Se fallirai, non ti costerà solo la corona ma anche la vita.”

“Adesso che cosa vuoi?” chiese il pappagallo e il gigante rispose:

“Se ti do la mia corona, devo avere in cambio qualcosa di ancora più bello e stavolta mi dovrai portare una corona di stelle.”

Il pappagallo se ne andò e appena fu fuori, mormorò:

“Rospo, vieni a me!” e fu subito un rospo che partì alla ricerca della corona di stelle.

Non era ancora andata molto lontano che giunse a una limpida pozza nella quale le stelle si riflettevano così lucenti che sembrano quasi vere da toccare e prendere con la mano. Chinandosi, riempì una borsa che si era portata con l’acqua scintillante e, tornando al castello, intrecciò una corona con le stelle riflesse. Allora gridò come aveva fatto prima:

“Pappagallo, vieni a me!” e con l’aspetto di un pappagallo andò davanti al gigante.

“Ecco la corona che hai chiesto.” disse, e stavolta il gigante non poté trattenere un grido di ammirazione. Riconobbe di essere stato battuto e prendendo la ghirlanda di rose, si rivolse alla ragazza.

“Il tuo potere è più grande del mio, prendi la corona, l’hai vinta giustamente!”

Il pappagallo non se lo fece dire due volte. Afferrando la corona, balzò fuori dalla finestra, gridando: “Scimmia, vieni a me!” e come scimmia la discesa giù dall’albero nel cortile non richiese che mezzo minuto. Quando fu a terra, disse di nuovo: “Formica, vieni a me!” e come piccola formica cominciò di nuovo a salire l’alto muro. Come fu contenta la formica di essere fuori dal castello del gigante, tenendo ben stretta la corona che si era ristretta proprio come lei, ma divenne di nuovo grande quando esclamò:

“Cerva, vieni a me!”

Di certo nessuna cerva corse mai come questa! Corse, oltrepassando i fiumi e passando attraverso piante aggrovigliate finché raggiunse il mare. Lì gridò per l’ultima volta:

“Pesce, vieni a me!” e sprofondando nell’acqua, nuotò sul fondo fino al palazzo in cui la regina e tutti i pesci erano riuniti ad aspettarla.

Il tempo dopo che se n’era andata era trascorso molto lentamente, come accade sempre a chi aspetta, e molti avevano perso completamente la speranza.

“Sono stanca di stare qui,” brontolò una splendida creaturina i cui colori cambiavano a ogni movimento del corpo. “Voglio vedere come va nel mondo di sopra. Devono essere mesi che la pesciolina se n’è andata.”

“Era un compito molto difficile e il gigante certamente l’avrà uccisa o sarebbe già tornata da tempo.” commentò un altro.

“Le giovani mosche saranno venute fuori adesso,” mormorò un terzo, “e saranno state mangiate tutte dai pesci del fiume! È davvero troppo!” quando improvvisamente si sentì una voce da dietro: “Guardate! Guardate! Che cos’è quella cosa lucente che viene piano verso di noi?” e la regina si alzò e rimase ritta sulla coda per quanto era eccitata.

Sulla folla cadde il silenzio e persino i brontoloni si calmarono e guardarono come tutti gli altri. Man mano la pesciolina avanzò, tenendo la corona con la bocca, e gli altri indietreggiarono per cederle il passo.

Lei andò dalla regina, la quale si chinò, e, prendendo la corona, se la mise sulla testa. Poi accadde una cosa meravigliosa. La sua coda cadde, o meglio, si divise e si trasformò in due gambe e nel paio di piedi più graziosi del mondo, mentre le sue damigelle, che si erano radunate intorno a lei, persero le scaglie e tornarono di nuovo fanciulle. Allora tutti si girarono e si guardarono dapprima gli uni gli altri e poi la pesciolinace, che aveva riacquistato il proprio aspetto ed era la più bella di tutti loro.

“È a te che dobbiamo il nostro ritorno alla vita, a te, a te!” gridavano e piangevano tutti di gioia.

Così tornarono tutti sulla terra e al palazzo della regina e dimenticarono completamente chi si trovava in fondo al mare. Ma erano mancati così a lungo che trovarono molti cambiamenti. Il principe, il marito della regina, era morto alcuni anni prima e al suo posto ora c’era il figlio, che era cresciuto ed era diventato re! Persino nella gioia di rivedere la madre sulla terra non lo abbandonava un’espressione triste e infine la regina non poté sopportarlo più a lungo e lo pregò di camminare con lei in giardino. Seduti insieme sotto un pergolato di gelsomini, presso il quale aveva trascorse tante ore da sposa, lei prese la mano del figlio e lo supplicò di dirle la causa della sua pena. “Perché se posso darti la felicità, l’avrai.” gli disse.

“Non è possibile,” rispose il principe “nessuno mi può aiutare. Devo sopportare in solitudine.”

“Rivelami infine il tuo dolore.” insistette la regina.

Lui disse; “Nessuno può farci nulla. Mi sono innamorato di chi non potrò mai sposare e dovrei essere un animale io stesso per poterlo fare.

“Potrebbe non essere impossibile come pensi,” rispose la regina “e in ogni modo, dimmi.”

Tra di loro vi fu un momento di silenzio poi, volgendo la testa, il principe rispose dolcemente:

“Mi sono innamorato di una bellissima cerva!”

“È tutto qui!” esclamò con gioia la regina. E gli disse in breve che, come aveva intuito, non era una cerva, ma una fanciulla sotto incantesimo che aveva conquistato per lei la corona l’aveva riportata a casa dal suo popolo.

“È qui, nel mio palazzo,” aggiunse la regina “ti condurrò da lei.”

Ma quando il principe fu davanti alla ragazza, che era ancora più bella di quanto avesse ami sognato, perse coraggio e rimase a testa china di fronte a lei.

Allora la fanciulla si avvicinò e i suoi occhi, mentre lo guardava, erano gli occhi della cerva di quel giorno nella foresta. Lei mormorò dolcemente:

“Per favore, lasciami andare e non uccidermi.”

E il principe si rammentò di quelle parole e il suo cuore si colmò di felicità. La regina sua madre li guardò e sorrise.

Da Racconti popolari catalani raccolti dal dott. D. Francisco de Sales Maspons y Labròs (1840-1901) folclorista, giureconsulto e notaio catalano.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)