The Bird of Truth

(MP3-21'30'')

Once upon a time there lived a poor fisher who built a hut on the banks of a stream which, shunning the glare of the sun and the noise of towns, flowed quietly past trees and under bushes, listening to the songs of the birds overhead.

One day, when the fisherman had gone out as usual to cast his nets, he saw borne towards him on the current a cradle of crystal. Slipping his net quickly beneath it he drew it out and lifted the silk coverlet. Inside, lying on a soft bed of cotton, were two babies, a boy and a girl, who opened their eyes and smiled at him. The man was filled with pity at the sight, and throwing down his lines he took the cradle and the babies home to his wife.

The good woman flung up her hands in despair when she beheld the contents of the cradle.

‘Are not eight children enough,’ she cried, ‘without bringing us two more? How do you think we can feed them?’

‘You would not have had me leave them to die of hunger,’ answered he, ‘or be swallowed up by the waves of the sea? What is enough for eight is also enough for ten.’

The wife said no more; and in truth her heart yearned over the little creatures. Somehow or other food was never lacking in the hut, and the children grew up and were so good and gentle that, in time, their foster-parents loved them as well or better than their own, who were quarrelsome and envious. It did not take the orphans long to notice that the boys did not like them, and were always playing tricks on them, so they used to go away by themselves and spend whole hours by the banks of the river. Here they would take out the bits of bread they had saved from their breakfast and crumble them for the birds. In return, the birds taught them many things: how to get up early in the morning, how to sing, and how to talk their language, which very few people knew.

But though the little orphans did their best to avoid quarrelling with their foster-brothers, it was very difficult always to keep the peace. Matters got worse and worse till, one morning, the eldest boy said to the twins:

‘It is all very well for you to pretend that you have such good manners, and are so much better than we, but we have at least a father and mother, while you have only got the river, like the toads and the frogs.’

The poor children did not answer the insult; but it made them very unhappy. And they told each other in whispers that they could not stay there any longer, but must go into the world and seek their fortunes.

So next day they arose as early as the birds and stole downstairs without anybody hearing them. One window was open, and they crept softly out and ran to the side of the river. Then, feeling as if they had found a friend, they walked along its banks, hoping that by-and-by they should meet some one to take care of them.

The whole of that day they went steadily on without seeing a living creature, till, in the evening, weary and footsore, they saw before them a small hut. This raised their spirits for a moment; but the door was shut, and the hut seemed empty, and so great was their disappointment that they almost cried. However, the boy fought down his tears, and said cheerfully:

‘Well, at any rate here is a bench where we can sit down, and when we are rested we will think what is best to do next.’

Then they sat down, and for some time they were too tired even to notice anything; but by-and-by they saw that under the tiles of the roof a quantity of swallows were sitting, chattering merrily to each other. Of course the swallows had no idea that the children understood their language, or they would not have talked so freely; but, as it was, they said whatever came into their heads.

‘Good evening, my fine city madam,’ remarked a swallow, whose manners were rather rough and countryfied, to another who looked particularly distinguished. ‘Happy, indeed, are the eyes that behold you! Only think of your having returned to your long-forgotten country friends, after you have lived for years in a palace!’

‘I have inherited this nest from my parents,’ replied the other, ‘and as they left it to me I certainly shall make it my home. But,’ she added politely, ‘I hope that you and all your family are well?’

‘Very well indeed, I am glad to say. But my poor daughter had, a short time ago, such bad inflammation in her eyes that she would have gone blind had I not been able to find the magic herb, which cured her at once.’

‘And how is the nightingale singing? Does the lark soar as high as ever? And does the linnet dress herself as smartly?’ But here the country swallow drew herself up.

‘I never talk gossip,’ she said severely. ‘Our people, who were once so innocent and well-behaved, have been corrupted by the bad examples of men. It is a thousand pities.’

‘What! innocence and good behaviour are not to be met with among birds, nor in the country! My dear friend, what are you saying?’

‘The truth and nothing more. Imagine, when we returned here, we met some linnets who, just as the spring and the flowers and the long days had come, were setting out for the north and the cold? Out of pure compassion we tried to persuade them to give up this folly; but they only replied with the utmost insolence.’

‘How shocking!’ exclaimed the city swallow.

‘Yes, it was. And, worse than that, the crested lark, that was formerly so timid and shy, is now no better than a thief, and steals maize and corn whenever she can find them.’

‘I am astonished at what you say.’

‘You will be more astonished when I tell you that on my arrival here for the summer I found my nest occupied by a shameless sparrow! “This is my nest,” I said. “Yours?” he answered, with a rude laugh. “Yes, mine; my ancestors were born here, and my sons will be born here also.” And at that my husband set upon him and threw him out of the nest. I am sure nothing of this sort ever happens in a town.’

‘Not exactly, perhaps. But I have seen a great deal—if you only knew!’

‘Oh! do tell us! do tell us!’ cried they all. And when they had settled themselves comfortably, the city swallow began:

‘You must know, then, that our king fell in love with the youngest daughter of a tailor, who was as good and gentle as she was beautiful. His nobles hoped that he would have chosen a queen from one of their daughters, and tried to prevent the marriage; but the king would not listen to them, and it took place. Not many months later a war broke out, and the king rode away at the head of his army, while the queen remained behind, very unhappy at the separation. When peace was made, and the king returned, he was told that his wife had had two babies in his absence, but that both were dead; that she herself had gone out of her mind and was obliged to be shut up in a tower in the mountains, where, in time, the fresh air might cure her.’

‘And was this not true?’ asked the swallows eagerly.

‘Of course not,’ answered the city lady, with some contempt for their stupidity. ‘The children were alive at that very moment in the gardener’s cottage; but at night the chamberlain came down and put them in a cradle of crystal, which he carried to the river.

‘For a whole day they floated safely, for though the stream was deep it was very still, and the children took no harm. In the morning—so I am told by my friend the kingfisher—they were rescued by a fisherman who lived near the river bank.’

The children had been lying on the bench, listening lazily to the chatter up to this point; but when they heard the story of the crystal cradle which their foster-mother had always been fond of telling them, they sat upright and looked at each other.

‘Oh, how glad I am I learnt the birds’ language!’ said the eyes of one to the eyes of the other.

Meanwhile the swallows had spoken again.

‘That was indeed good fortune!’ cried they.

‘And when the children are grown up they can return to their father and set their mother free.’

‘It will not be so easy as you think,’ answered the city swallow, shaking her head; ‘for they will have to prove that they are the king’s children, and also that their mother never went mad at all. In fact, it is so difficult that there is only one way of proving it to the king.’

‘And what is that?’ cried all the swallows at once. ‘And how do you know it?’

‘I know it,’ answered the city swallow ‘because, one day, when I was passing through the palace garden, I met a cuckoo, who, as I need not tell you, always pretends to be able to see into the future. We began to talk about certain things which were happening in the palace, and of the events of past years. “Ah,” said he, “the only person who can expose the wickedness of the ministers and show the king how wrong he has been is the Bird of Truth, who can speak the language of men.”

‘“And where can this bird be found?” I asked.

‘“It is shut up in a castle guarded by a fierce giant, who only sleeps one quarter of an hour out of the whole twenty-four,” replied the cuckoo.’

‘And where is this castle?’ inquired the country swallow, who, like all the rest, and the children most of all, had been listening with deep attention.

‘That is just what I don’t know,’ answered her friend. ‘All I can tell you is that not far from here is a tower, where dwells an old witch, and it is she who knows the way, and she will only teach it to the person who promises to bring her the water from the fountain of many colours, which she uses for her enchantments. But never will she betray the place where the Bird of Truth is hidden, for she hates him, and would kill him if she could; knowing well, however, that this bird cannot die, as he is immortal, she keeps him closely shut up, and guarded night and day by the Birds of Bad Faith, who seek to gag him so that his voice should not be heard.’

‘And is there no one else who can tell the poor boy where to find the bird, if he should ever manage to reach the tower?’ asked the country swallow.

‘No one,’ replied she, ‘except an owl, who lives a hermit’s life in that desert, and he knows only one word of man’s speech, and that is “cross.” So that even if the prince did succeed in getting there, he could never understand what the owl said. But, look, the sun is sinking to his nest in the depths of the sea, and I must go to mine. Good-night, friends, good-night!’

Then the swallow flew away, and the children, who had forgotten both hunger and weariness in the joy of this strange news, rose up and followed in the direction of her flight. After two hours’ walking, they arrived at a large city, which they felt sure must be the capital of their father’s kingdom. Seeing a good-natured looking woman standing at the door of a house, they asked her if she would give them a night’s lodging, and she was so pleased with their pretty faces and nice manners that she welcomed them warmly.

It was scarcely light the next morning before the girl was sweeping out the rooms, and the boy watering the garden, so that by the time the good woman came downstairs there was nothing left for her to do. This so delighted her that she begged the children to stay with her altogether, and the boy answered that he would leave his sister with her gladly, but that he himself had serious business on hand and must not linger in pursuit of it. So he bade them farewell and set out.

For three days he wandered by the most out-of-the-way paths, but no signs of a tower were to be seen anywhere. On the fourth morning it was just the same, and, filled with despair, he flung himself on the ground under a tree and hid his face in his hands. In a little while he heard a rustling over his head, and looking up, he saw a turtle dove watching him with her bright eyes.

‘Oh dove!’ cried the boy, addressing the bird in her own language, ‘Oh dove! tell me, I pray you, where is the castle of Come-and-never-go?’

‘Poor child,’ answered the dove, ‘who has sent you on such a useless quest?’

‘My good or evil fortune,’ replied the boy, ‘I know not which.’

‘To get there,’ said the dove, ‘you must follow the wind, which to-day is blowing towards the castle.’

The boy thanked her, and followed the wind, fearing all the time that it might change its direction and lead him astray. But the wind seemed to feel pity for him and blew steadily on.

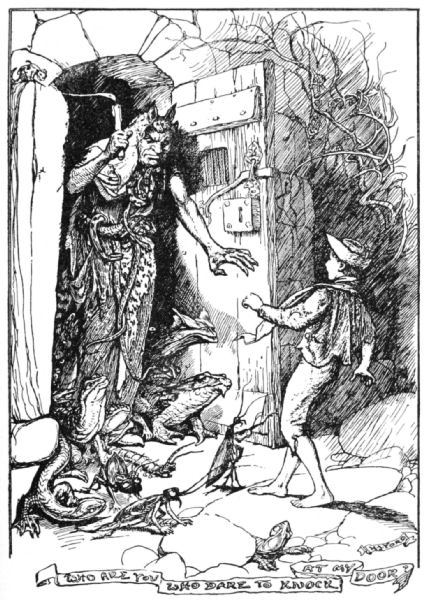

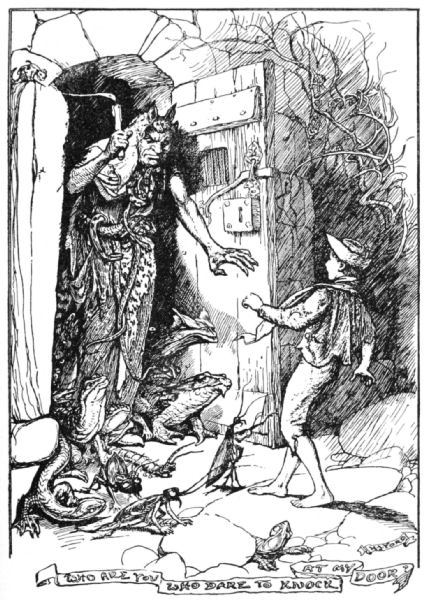

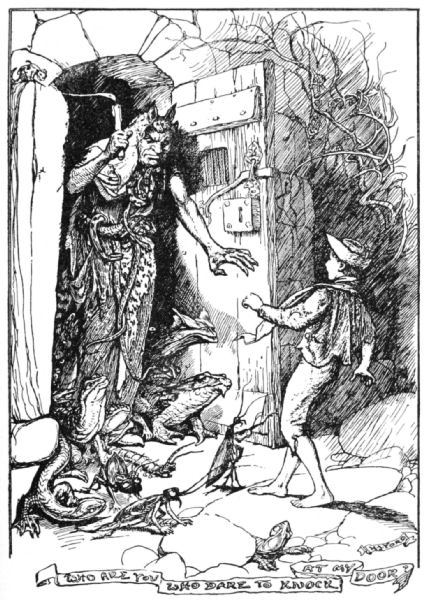

With each step the country became more and more dreary, but at nightfall the child could see behind the dark and bare rocks something darker still. This was the tower in which dwelt the witch; and seizing the knocker he gave three loud knocks, which were echoed in the hollows of the rocks around.

The door opened slowly, and there appeared on the threshold an old woman holding up a candle to her face, which was so hideous that the boy involuntarily stepped backwards, almost as frightened by the troop of lizards, beetles, and such creatures that surrounded her, as by the woman herself.

‘Who are you who dare to knock at my door and wake me?’ cried she. ‘Be quick and tell me what you want, or it will be the worse for you.’

‘Madam,’ answered the child, ‘I believe that you alone know the way to the castle of Come-and-never-go, and I pray you to show it to me.’

‘Very good,’ replied the witch, with something that she meant for a smile, ‘but to-day it is late. To-morrow you shall go. Now enter, and you shall sleep with my lizards.’

‘I cannot stay,’ said he. ‘I must go back at once, so as to reach the road from which I started before day dawns.’

‘If I tell you, will you promise me that you will bring me this jar full of the many-coloured water from the spring in the courtyard of the castle?’ asked she. ‘If you fail to keep your word I will change you into a lizard for ever.’

‘I promise,’ answered the boy.

Then the old woman called to a very thin dog, and said to him:

‘Conduct this pig of a child to the castle of Come-and-never-go, and take care that you warn my friend of his arrival.’ And the dog arose and shook itself, and set out.

At the end of two hours they stopped in front of a large castle, big and black and gloomy, whose doors stood wide open, although neither sound nor light gave sign of any presence within. The dog, however, seemed to know what to expect, and, after a wild howl, went on; but the boy, who was uncertain whether this was the quarter of an hour when the giant was asleep, hesitated to follow him, and paused for a moment under a wild olive that grew near by, the only tree which he had beheld since he had parted from the dove. ‘Oh, heaven, help me!’ cried he.

‘Cross! cross!’ answered a voice.

The boy leapt for joy as he recognised the note of the owl of which the swallow had spoken, and he said softly in the bird’s language:

‘Oh, wise owl, I pray you to protect and guide me, for I have come in search of the Bird of Truth. And first I must fill this jar with the many-coloured water in the courtyard of the castle.’

‘Do not do that,’ answered the owl, ‘but fill the jar from the spring which bubbles close by the fountain with the many-coloured water. Afterwards, go into the aviary opposite the great door, but be careful not to touch any of the bright-plumaged birds contained in it, which will cry to you, each one, that he is the Bird of Truth. Choose only a small white bird that is hidden in a corner, which the others try incessantly to kill, not knowing that it cannot die. And, be quick!—for at this very moment the giant has fallen asleep, and you have only a quarter of an hour to do everything.’

The boy ran as fast as he could and entered the courtyard, where he saw the two springs close together. He passed by the many-coloured water without casting a glance at it, and filled the jar from the fountain whose water was clear and pure. He next hastened to the aviary, and was almost deafened by the clamour that rose as he shut the door behind him. Voices of peacocks, voices of ravens, voices of magpies, each claiming to be the Bird of Truth. With steadfast face the boy walked by them all, to the corner where, hemmed in by a band of fierce crows, was the small white bird he sought. Putting her safely in his breast, he passed out, followed by the screams of the Birds of Bad Faith which he left behind him.

Once outside, he ran without stopping to the witch’s tower, and handed to the old woman the jar she had given him.

‘Become a parrot!’ cried she, flinging the water over him. But instead of losing his shape, as so many had done before, he only grew ten times handsomer; for the water was enchanted for good and not ill. Then the creeping multitude around the witch hastened to roll themselves in the water, and stood up, human beings again.

When the witch saw what was happening, she took a broomstick and flew away.

Who can guess the delight of the sister at the sight of her brother, bearing the Bird of Truth? But although the boy had accomplished much, something very difficult yet remained, and that was how to carry the Bird of Truth to the king without her being seized by the wicked courtiers, who would be ruined by the discovery of their plot.

Soon—no one knew how—the news spread abroad that the Bird of Truth was hovering round the palace, and the courtiers made all sorts of preparations to hinder her reaching the king.

They got ready weapons that were sharpened, and weapons that were poisoned; they sent for eagles and falcons to hunt her down, and constructed cages and boxes in which to shut her up if they were not able to kill her. They declared that her white plumage was really put on to hide her black feathers—in fact there was nothing they did not do in order to prevent the king from seeing the bird or from paying attention to her words if he did.

As often happens in these cases, the courtiers brought about that which they feared. They talked so much about the Bird of Truth that at last the king heard of it, and expressed a wish to see her. The more difficulties that were put in his way the stronger grew his desire,and in the end the king published a proclamation that whoever found the Bird of Truth should bring her to him without delay.

As soon as he saw this proclamation the boy called his sister, and they hastened to the palace. The bird was buttoned inside his tunic, but, as might have been expected, the courtiers barred the way, and told the child that he could not enter. It was in vain that the boy declared that he was only obeying the king’s commands; the courtiers only replied that his majesty was not yet out of bed, and it was forbidden to wake him.

They were still talking, when, suddenly, the bird settled the question by flying upwards through an open window into the king’s own room. Alighting on the pillow, close to the king’s head, she bowed respectfully, and said:

‘My lord, I am the Bird of Truth whom you wished to see, and I have been obliged to approach you in this manner because the boy who brought me is kept out of the palace by your courtiers.’

‘They shall pay for their insolence,’ said the king. And he instantly ordered one of his attendants to conduct the boy at once to his apartments; and in a moment more the prince entered, holding his sister by the hand.

‘Who are you?’ asked the king; ‘and what has the Bird of Truth to do with you?’

‘If it please your majesty, the Bird of Truth will explain that herself,’ answered the boy.

And the bird explain; and the king heard for the first time of the wicked plot that had been successful for so many years. He took his children in his arms, with tears in his eyes, and hurried off with them to the tower in the mountains where the queen was shut up. The poor woman was as white as marble, for she had been living almost in darkness; but when she saw her husband and children, the colour came back to her face, and she was as beautiful as ever.

They all returned in state to the city, where great rejoicings were held. The wicked courtiers had their heads cut off, and all their property was taken away. As for the good old couple, they were given riches and honour, and were loved and cherished to the ends of their lives.

From Cuentos, Oraciones, y Adivinas, por Fernan Caballero.

L'Uccello della Verità

C’era una volta un povero pescatore che aveva costruito una capanna sulle rive di un fiume che, sfuggendo la luce del sole e il rumore delle città, scorreva tranquillamente tra gli alberi e sotto i cespugli, ascoltando i canti degli uccelli lassù.

Un giorno in cui il pescatore era andato come il solito a gettare le reti, vide una culla di cristallo che la corrente trascinava verso di lui. Facendole scivolare sotto la rete, la tirò a sé e sollevò la copertina di seta. all’interno, sdraiati su un soffice letto di cotone, c’erano due bambini, un maschio e una femmina, che aprirono gli occhi e gli sorrisero. A quella vista l’uomo fu preso da grande compassione e, gettando le corde, portò la culla e i bambini a casa dalla moglie.

La brava donna alzò le mani disperata quando vide il contenuto della culla.

“Non sono già abbastanza otto bambini senza portarcene altri due?” gridò “Come pensi che potremo nutrirli?”

“Non avresti voluto che li lasciassi morire di fame o fossero inghiottiti dalle onde del mare?” rispose lui “Ciò che basta per otto, basterà anche per dieci.”

La moglie non disse altro e in verità il suo cuore provava tenerezza per le creaturine. In un modo o nell’altro il cibo non mancò mai nella capanna e i bambini crebbero ed erano così buoni e gentili che i loro genitori adottivi li amavano quanto e più dei loro stessi figli, i quali erano litigiosi e invidiosi. Non ci volle molto agli orfani per accorgersi che i bambini non li amavano e facevano sempre loro dispetti, così si abituarono ad andare via per conto loro e a trascorrere tutto il tempo sulle rive del fiume. Qui potevano prendere i pezzetti di pane sottratti alla colazione e sbriciolarli per gli uccelli. In cambio gli uccelli insegnavano loro molte cose: come alzarsi presto la mattina, come cantare e come parlare la loro lingua che ben poca gente conosceva.

Sebbene gli orfanelli facessero del loro meglio per evitare le liti con i fratellastri, era sempre difficile restare in pace. Le cose andarono sempre peggio e una mattina il maggiore dei ragazzi disse ai gemelli:

“Vi riesce molto bene fingere di avere così buone maniere e di essere migliori di noi, ma infine noi abbiamo un padre e una madre mentre voi avete ottenuto solo il fiume, come i rospi e le rane.”

I poveri bambini non risposero all’insulto, ma li rese molto infelici. Si sussurrarono l’un l’altra che non sarebbero potuti restare lì ancora più a lungo ma che dovevano andare per il mondo in cerca di fortuna.

Così il giorno seguente si alzarono di buon’ora come gli uccelli e scesero furtivamente al piano inferiore senza che nessuno li sentisse. Una finestra era aperta e sgusciarono fuori pian piano poi corsero verso il fiume. Lì, sentendosi come se avessero trovato un amico, camminarono lungo le rive sperando di lì a non molto di incontrare qualcuno che si prendesse cura di loro.

Quasi l’intero giorno trascorse tranquillamente senza che vedessero creatura vivente finché, verso sera, stanchi e con i piedi doloranti, videro davanti a loro una piccola capanna. Ciò risollevò loro lo spirito per un attimo, ma la porta era chiusa e la capanna sembrava vuota e fu così grande il loro disappunto che quasi piansero. In ogni modo il bambino ricacciò indietro le lacrime e disse allegramente:

“Ebbene, in ogni modo qui c’è una panca sulla quale ci possiamo sedere e, quando avremo riposato, penseremo a ciò che sia meglio fare.”

Allora sedettero e per un po’ di tempo, siccome erano molto stanchi, non si accorsero di nulla; poi pian piano videro che sotto le tegole del tetto c’era una gran quantità di passeri che stavano cinguettando allegramente gli uni con gli altri. Naturalmente i passeri non immaginavano che i bambini comprendessero il loro linguaggio o non avrebbero parlato così liberamente; ma stando così le cose, dicevano qualsiasi cosa passasse loro per la testa.

“Buonasera, mia bella dama di città,” disse una passerotta, le cui maniere erano piuttosto rozze e campagnole, a un altra dall’aspetto particolarmente distinto. “In verità, felici gli occhi che vi vedono! Penso che dobbiate tornare dagli amici campagnoli a lungo dimenticati dopo che avete vissuto per anni in un palazzo.”

“Ho ereditato questo nido dai miei genitori,” rispose l’altra, “ e se me l’hanno lasciato, certamente ne farò casa mia.” poi aggiunse educatamente “Voi e la vostra famiglia state bene, spero.”

“Assai bene, mi fa piacere dirlo. Ma la mia povera figlia un po’ di tempo fa ha avuto una brutta infiammazione agli occhi e sarebbe diventata cieca se non fossi stato capace di trovare l’erba magica che l’ha subito curata.”

“E che cosa sta cantando l’usignolo? L’allodola vola in alto come sempre? E il fanello si veste sempre così vivacemente?” Ma a questo punto la passerotta campagnola si fermò.

“Non faccio mai pettegolezzi,” disse gravemente. “Il nostro popolo, che una volta era così innocente e si comportava bene, è stato corrotto dal cattivo esempio degli uomini. È un gran peccato.”

“Che cosa? L’innocenza e le buone maniere non si riscontrano tra gli uccelli né in campagna! Mia cara amica, che state dicendo?”

“La verità e niente altro. Immaginate, quando siamo tornati qui, abbiamo incontrato alcuni fanelli i quali, appena giunti la primavera, i fiori e le lunghe giornate, stavano partendo per il nord e il freddo? Solo per pura compassione abbiamo tentato di convincerli ad abbandonare una tale follia, eppure ci hanno risposto con la massima insolenza.”

“Stupefacente!” esclamò la passerotta di città.

“Sì, e, peggio ancora, l’allodola con la cresta, che un tempo era così timida e ritrosa, adesso non è meglio di un ladro e ruba granturco e grano ogni volta in cui li trovi.”

“Sono sgomenta per ciò che dite.”

“E lo sarete ancor di più quando vi dirò che al mio arrivo qui in estate ho trovato il nido occupato da un passero sfrontato! ‘Questo è il mio nido.’ ho detto. ‘Vostro?’ ha risposto con una risata insolente. ‘Sì, il mio; i miei antenati sono nati qui e anche i miei figli vi nasceranno.’ E a questo punto mio marito gli si è avvicinato e lo ha gettato fuori dal nido. Sono sicura che in città non accada nulla del genere.”

“Non proprio così, forse. Ma ho visto tante cose… se solo sapeste!”

“Ditecele! Ditecele!” gridarono tutti. E quando si furono sistemati comodamente, la passerotta di città cominciò:

“Allora dovete sapere che il nostro re si era innamorato della figlia minore di un sarto, la quale era tanto buona e gentile quanto era bella. I suoi nobili speravano che avrebbe scelto come regina una delle loro figlie e cercarono di impedire il matrimonio; il re però non volle ascoltarli e fu celebrato. Dopo pochi mesi scoppiò una guerra e il re partì alla testa dell’esercito mentre la regina rimase a casa, assai infelice per la separazione. Quando fu stipulata la pace e il re fu tornato, gli fu detto che in sua assenza la moglie aveva avuto due bambini, ma che erano morti entrambi, così lei era uscita di senno ed era stata costretta a farsi rinchiudere in una torre tra le montagne dove, con il tempo, l’aria fresca l’avrebbe curata.”

“E non era vero?” chiesero i passeri avidamente.

“Naturalmente no,” rispose la passerotta di città con un po’ di disprezzo per la loro stupidità. “ I bambini in quel momento vivevano nella casa del giardiniere, ma di notte il ciambellano venne a prenderli e li mise in una culla di cristallo che portò al fiume.”

“Per un po’ di giorni navigarono sani e salvi perché sebbene il fiume fosse profondo era molto lento e ai bambini non accadde alcun male. Una mattina – così mi è stato detto dal mio amico martin pescatore – sono stati salvati da un pescatore che viveva vicino alla riva del fiume.”

I bambini erano sdraiati sulla panca, ascoltando pigramente fino a quel momento il chiacchiericcio, ma quando udirono la storia della culla di cristallo che alla madre adottiva era sempre piaciuto raccontare loro, sedettero dritti e si guardarono l’un l’altra.

‘Come sono contento di aver imparato il linguaggio degli uccelli!ì diceva lo sguardo dell’uno allo sguardo dell’altra.

Nel frattempo i passeri avevano parlato di nuovo.

“È stata davvero una fortuna!” esclamarono.

“E quando i bambini saranno cresciuti, potranno tornare dal padre e liberare la madre.”

“Non sarà così facile come pensate,” rispose la passerotta di città, scuotendo la testa, “perché dovranno provare di essere i figli del re e anche che la loro madre non è affatto pazza. Infatti è così difficile che hanno un solo modo per provarlo al re.”

“E qual è?” gridarono subito tutti i passeri “E come lo conoscete?”

La passerotta di città rispose: “Lo conosco perché un giorno, quando stavo passando per il giardino del palazzo, ho incontrato un cuculo il quale, non c’è bisogno che ve lo dica, voleva sempre far credere di vedere nel futuro. Cominciammo a parlare di certe cose che erano accadute a palazzo e di fatti degli anni passati. Disse: ‘L’unica persona che può smascherare la la malvagità dei ministri e mostrare al re quanto si sia sbagliato è l’Uccello della Verità che può parlare il linguaggio degli uomini.’

‘“E dove si può trovare questo uccello?’ chiesi.

‘“È chiuso in un castello sorvegliato da un crudele gigante che dome solo un quarto d’ora su ventiquattro.’ rispose il cuculo.”

“E dov’è il castello?” chiese la passerotta di campagna che, come tutti gli altri, e i bambini più di tutti, aveva ascoltato con profonda attenzione.

“È proprio ciò che non so.” rispose l’amica. “Tutto ciò che posso dirvi è che non lontano da qui c’è una torre in cui abita una vecchia strega e lei conosce la via e la mostrerà solo alla persona che prometterà di portarle l’acqua dalla fontana multicolore che usa per i suoi incantesimi. Ma non svelerà mai il luogo in cui l’Uccello della Verità è nascosto perché lo odia e lo ucciderebbe, se potesse; tuttavia sapendo bene che l’uccello non può morire perché è immortale, lo tiene segregato lo fa sorvegliare giorno e notte dagli Uccelli della Malafede, che cercano di imbavagliarlo così che la sua voce non si possa sentire.”

“E non c’è nessuno che possa dire al povero bambino dove trovare l’uccello, se volesse provare a raggiungere la torre?” chiese la passerotta di campagna.

“Nessuno tranne un gufo, che conduce una vita da eremita in quel deserto e conosce una sola parola del linguaggio umano che è ‘croce’. Rispose “ così anche se il principe ci riuscisse, non potrebbe mai capire ciò che dice il gufo. Guardate, il sole sta calando nel suo nido nelle profondità marine e io devo andare nel mio. Buonanotte, amici, buonanotte!”

Poi la passerotta volò via e i bambini, che per la gioia avevano dimenticato sia la fame che la stanchezza, si alzarono e seguirono la direzione del suo volo. Dopo aver camminato per un paio d’ore, giunsero in una grande città che capirono fosse la capitale del regno del loro padre. Vedendo una donna dall’aspetto benevolo sulla porta di una casa, le chiesero se volesse dar loro riparo per la notte e lei fu così compiaciuta per i loro bei visetti e per le buone maniere che li accolse calorosamente.

Stava appena facendo giorno la mattina seguente che la bambina stava spazzando le stanze e il bambino stava innaffiando il giardino così che, nel momento in cui la vecchina scese al piano inferiore, non le era rimasto nulla da fare. Ne fu così contenta che pregò i bambini di restare insieme con lei e il bambino rispose che avrebbe lasciato volentieri con lei la sorella ma che lui doveva affrontare un’impresa importante e non poteva indugiare nel perseguirla. Così disse loro addio e partì.

Camminò per tre giorni sui sentieri più fuori mano, ma non si vedeva traccia della torre da nessuna parte. La quarta mattina fu come le altre e , disperato, si gettò a terra sotto un albero e nascose il volto tra le mani. Di lì a poco udì un fruscio sopra la testa e, guardando in su, vide una tortora che lo osservava con gli occhietti brillanti.

“Oh, colomba!” gridò il bambino, rivolgendosi all’uccello nel suo linguaggio, “oh, colomba! Dimmi, ti prego, dov’è il Castello di Vieni-E-Mai-Vai?”

“Povero bambino,” rispose la colomba, “chi ti fa rivolgere una simile vana domanda?”

“La mia buona o cattiva sorte.” rispose il bambino, “Non so quale.”

“Per andare là” disse la colomba “devi seguire il vento che oggi sta soffiando verso il castello.”

Il bambino la ringraziò e seguì il vento, temendo per tutto il tempo che potesse cambiare direzione e condurlo fuori strada. Ma il vento sembrò avere pietà di lui e soffiò con costanza.

Ad ogni passo il paesaggio diventava sempre più desolato ma al calar della notte il bambino poté vedere dietro le buie e spoglie rocce qualcosa di ancora più oscuro. Era la torre in cui abitava la strega; afferrando il batacchio, diede tre sonori colpi che riecheggiarono nelle cavità delle rocce circostanti.

La porta si aprì lentamente e apparve sulla soglia una vecchia che teneva una candela vicino al viso ed era così orribile che il bambino fece involontariamente un passo indietro, terrorizzato sia dalla schiera di lucertole, scarafaggi e altre creature simili che la circondavano e sia dalla donna stessa.

“Chi sei tu che osi bussare alla mia porta e svegliarmi?” gridò. “Sbrigati a dirmi che cosa vuoi o sarà peggio per te.”

“Signora,” rispose il bambino, “credo che voi sola conosciate la strada per il Castello di Vieni-E-Mai-Vai e vi prego di mostrarmela.”

“Benissimo,” rispose la strega, con una smorfia che lei riteneva simile a un sorriso, “ma oggi è tardi. Andrai domani. Adesso entra e dormirai con le mie lucertole.”

“Non posso restare,” disse il bambino. “Devo andare subito così da poter raggiungere la strada dalla quale partire appena farà giorno.”

“Se te lo dico, mi prometti che mi porterai questa brocca piena dell’acqua multicolore dalla sorgente nel cortile del castello?” chiese la strega. “Se non manterrai la parola, ti trasformerò per sempre in una lucertola.”

“Lo prometto.” rispose il bambino.

Allora la vecchia chiamò un cane assai piccolo e gli disse:

“Conduci questo sudicio bambino al Castello di Vieni-E-Mai-Vai e mi raccomando di avvisare il mio amico del suo arrivo.” E il cane si alzò, si scrollò e partì.

Dopo due ore si fermarono di fronte a un vasto castello, grande e nero e tetro, le cui ampie porte erano aperte sebbene né suoni né luci indicassero alcuna presenza all’interno. In ogni modo il cane sembrava sapere ciò che lo aspettava e, dopo un furioso latrato, entrò; ma il bambino, che era incerto se fosse quello il quarto d’ora in cui il gigante dormiva, esitava a seguirlo e si fermò un momento sotto un ulivo che cresceva lì vicino, l’unico albero che avesse visto da quando si era separato dalla colomba. “Oh, cielo, aiutami!” esclamò.

“Croce! Croce!” rispose una voce.

Il bambino fece un balzo di gioia nel riconoscere l’accento del gufo del quale aveva parlato la passerotta e disse sottovoce nel linguaggio degli uccelli:

“Saggio gufo, ti prego di proteggermi e di guidarmi perché sono venuto in cerca dell’Uccello della Verità. Prima devo riempire questa brocca con l’acqua multicolore nel cortile del castello.”

“Non farlo,” rispose il gufo, “ riempi invece la brocca con la sorgente che gorgoglia vicino alla fontana dell’acqua multicolore. Dopo vai nella voliera di fronte alla grande porta ma stai bene attento a non toccare nessuno degli uccelli dalle piume lucenti che contiene perché ciascuno ti griderà di essere l’Uccello della Verità. Scegli solo un piccolo uccello bianco che si nasconde in un angolo, che gli altri tentano incessantemente di uccidere, non sapendo che non può morire. Sbrigati! Proprio in questo momento il gigante si è addormentato e tu avrai solo un quarto d’ora per fare tutto.”

Il bambino corse più veloce che poté ed entrò nel cortile in cui vide le due sorgenti vicine. Oltrepassò quella dall’acqua multicolore senza darle un’occhiata e riempì la brocca dalla fontana la cui acqua era limpida e pura. Poi si affrettò verso la voliera e fu quasi assordato dal clamore che si levò quando chiuse la porta dietro di sé. Voci di pavoni, di corvi, di cornacchie, ognuna che affermava di essere l’Uccello della Verità. Con espressione risoluta il bambino li oltrepassò tutti fino all’angolo in cui, circondato da uno stormo di feroci corvi, vide che c’era il piccolo uccello bianco. Mettendolo in salvo nel petto, se ne andò, seguito dalle grida degli Uccelli della Malafede che si lasciava dietro.

Una volta fuori, corse senza fermarsi fino alla torre della strega e porse alla vecchia la brocca che lei gli aveva dato.

“Diventa un pappagallo!” gridò la vecchia, gettandogli addosso l’acqua. Ma invece di mutare aspetto, come tanti prima di lui avevano fatto, divenne dieci volte più bello perché l’acqua era incantata per fare il bene e non il male. Poi la moltitudine strisciante intorno alla strega si affrettò a rotolarsi nell’acqua e, alzandosi in piedi, riebbe aspetto umano.

Quando la strega vide ciò che stava accadendo, afferrò un manico di scopa e volò via.

Chi può immaginare la gioia della sorella alla vista del fratello che portava l’Uccello della Verità? Ma sebbene il bambino compiuto una grande impresa, rimaneva ancora qualcosa di molto difficile ed era come portare l’Uccello della Verità al re senza essere catturati dai perfidi cortigiani che sarebbero stati rovinati dalla rivelazione del loro piano.

Ben presto, nessuno sapeva come, si diffuse la notizia che l’Uccello della Verità stava volando intorno al palazzo e i cortigiani architettarono ogni sorta di espedienti per impedirgli di raggiungere il re.

Prepararono armi che erano affilate e armi che erano avvelenate; mandarono aquile e falconi a dargli la caccia, costruirono gabbie e casse in cui rinchiuderlo se non fossero stati in grado di ucciderlo. Affermarono che il suo piumaggio bianco in realtà nascondeva penne nere, infatti non c’era nulla che non avrebbero tentato per impedire al re di vedere l’uccello o per distogliere la sua attenzione dalle parole dell’uccello se lo avesse visto.

Come spesso accade in questi casi, i cortigiani furono la causa di ciò che temevano. Parlarono tanto dell’Uccello della Verità che alla fine il re sentì ed espresse il desiderio di vederlo. Le molte difficoltà che gli furono opposte fecero diventare più forte il suo desiderio e alla fine emanò un proclama con il quale chiunque avesse trovato l’Uccello della Verità doveva portarglielo senza indugio.

Appena vide il proclama, il bambino chiamò la sorella e si affrettarono verso il palazzo. l’uccello era al sicuro nella tunica del bambino ma, come ci si aspettava, i cortigiani sbarrarono loro la strada e dissero al bambino che non sarebbe entrato. Invano il bambino dichiarò che stava solo obbedendo all’ordine del re, i cortigiani risposero solo che sua maestà non si era ancora alzato dal letto ed era proibito svegliarlo.

Stavano ancora parlando quando, improvvisamente, l’uccello risolse il problema volando in alto verso la finestra aperta della camera del re. Posandosi sul cuscino, vicino alla testa del re, s’inchinò rispettosamente e disse:

“Mio signore, sono l’Uccello della Verità che hai desiderato vedere e sono stato obbligato ad avvicinarmi a voi in questo modo perché il bambino che mi portava è trattenuto fuori dal palazzo dai vostri cortigiani.”

“Pagheranno per la loro insolenza.” disse il re. E ordinò immediatamente a uno degli attendenti di condurre subito il bambino nei suoi appartamenti e un attimo dopo il principe entrò, tenendo per mano la sorella.

“Chi siete e che cosa ha che fare con voi l’Uccello della Verità?” chiese il re.

“Se a vostra maestà piace, lo stesso Uccello della Verità lo spiegherà.” rispose il bambino.

E l’uccello spiegò. Per la prima volta il re udì il malvagio piano che per tanti anni aveva avuto successo. Prese tra le braccia i bambini, con le lacrime agli occhi, e si affrettò con loro alla torre tra le montagne in cui era rinchiusa la regina. La povera donna era bianca come il marmo perché viveva quasi nelle tenebre, ma quando vide il marito e i figli il colore le rifluì al viso e fu più bella che mai.

Tornarono tutti in città dove ci fu grande gioia. I malvagi cortigiani furono decapitati e tutte le loro proprietà confiscate. Quanto alla vecchia e buona coppia, furono dati loro ricchezze e onori e fu amata e curata teneramente fino alla morte.

Da Favole, preghiere e profezie raccolte da Fernan Caballero.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)