Once upon a time the things in this story happened, and if they had not happened then the story would never have been told. But that was the time when wolves and lambs lay peacefully together in one stall, and shepherds dined on grassy banks with kings and queens.

Once upon a time, then, my dear good children, there lived a man. Now this man was really a hundred years old, if not fully twenty years more. And his wife was very old too—how old I do not know; but some said she was as old as the goddess Venus herself. They had been very happy all these years, but they would have been happier still if they had had any children; but old though they were they had never made up their minds to do without them, and often they would sit over the fire and talk of how they would have brought up their children if only some had come to their house.

One day the old man seemed sadder and more thoughtful than was common with him, and at last he said to his wife: 'Listen to me, old woman!'

'What do you want?' asked she.

'Get me some money out of the chest, for I am going a long journey—all through the world—to see if I cannot find a child, for my heart aches to think that after I am dead my house will fall into the hands of a stranger. And this let me tell you: that if I never find a child I shall not come home again.'

Then the old man took a bag and filled it with food and money, and throwing it over his shoulders, bade his wife farewell.

For long he wandered, and wandered, and wandered, but no child did he see; and one morning his wanderings led him to a forest which was so thick with trees that no light could pass through the branches. The old man stopped when he saw this dreadful place, and at first was afraid to go in; but he remembered that, after all, as the proverb says: 'It is the unexpected that happens,' and perhaps in the midst of this black spot he might find the child he was seeking. So summoning up all his courage he plunged boldly in.

How long he might have been walking there he never could have told you, when at last he reached the mouth of a cave where the darkness seemed a hundred times darker than the wood itself. Again he paused, but he felt as if something was driving him to enter, and with a beating heart he stepped in.

For some minutes the silence and darkness so appalled him that he stood where he was, not daring to advance one step. Then he made a great effort and went on a few paces, and suddenly, far before him, he saw the glimmer of a light. This put new heart into him, and he directed his steps straight towards the faint rays, till he could see, sitting by it, an old hermit, with a long white beard.

The hermit either did not hear the approach of his visitor, or pretended not to do so, for he took no notice, and continued to read his book. After waiting patiently for a little while, the old man fell on his knees, and said: 'Good morning, holy father!' But he might as well have spoken to the rock. 'Good morning, holy father,' he said again, a little louder than before, and this time the hermit made a sign to him to come nearer. 'My son,' whispered he, in a voice that echoed through the cavern, 'what brings you to this dark and dismal place? Hundreds of years have passed since my eyes have rested on the face of a man, and I did not think to look on one again.'.

'My misery has brought me here,' replied the old man; 'I have no child, and all our lives my wife and I have longed for one. So I left my home, and went out into the world, hoping that somewhere I might find what I was seeking.'

Then the hermit picked up an apple from the ground, and gave it to him, saying: 'Eat half of this apple, and give the rest to your wife, and cease wandering through the world.'

The old man stooped and kissed the feet of the hermit for sheer joy, and left the cave. He made his way through the forest as fast as the darkness would let him, and at length arrived in flowery fields, which dazzled him with their brightness. Suddenly he was seized with a desperate thirst, and a burning in his throat. He looked for a stream but none was to be seen, and his tongue grew more parched every moment. At length his eyes fell on the apple, which all this while he had been holding in his hand, and in his thirst he forgot what the hermit had told him, and instead of eating merely his own half, he ate up the old woman's also; after that he went to sleep.

When he woke up he saw something strange lying on a bank a little way off, amidst long trails of pink roses. The old man got up, rubbed his eyes, and went to see what it was, when, to his surprise and joy, it proved to be a little girl about two years old, with a skin as pink and white as the roses above her. He took her gently in his arms, but she did not seem at all frightened, and only jumped and crowed with delight; and the old man wrapped his cloak round her, and set off for home as fast as his legs would carry him.

When they were close to the cottage where they lived he laid the child in a pail that was standing near the door, and ran into the house, crying: 'Come quickly, wife, quickly, for I have brought you a daughter, with hair of gold and eyes like stars!'

At this wonderful news the old woman flew downstairs, almost tumbling down ill her eagerness to see the treasure; but when her husband led her to the pail it was perfectly empty! The old man was nearly beside himself with horror, while his wife sat down and sobbed with grief and disappointment. There was not a spot round about which they did not search, thinking that somehow the child might have got out of the pail and hidden itself for fun; but the little girl was not there, and there was no sign of her.

'Where can she be?' moaned the old man, in despair. 'Oh, why did I ever leave her, even for a moment? Have the fairies taken her, or has some wild beast carried her off?' And they began their search all over again; but neither fairies nor wild beasts did they meet with, and with sore hearts they gave it up at last and turned sadly into the hut.

And what had become of the baby? Well, finding herself left alone in a strange place she began to cry with fright, and an eagle hovering near, heard her, and went to see what the sound came from. When he beheld the fat pink and white creature he thought of his hungry little ones at home, and swooping down he caught her up in his claws and was soon flying with her over the tops of the trees. In a few minutes he reached the one in which he had built his nest, and laying little Wildrose (for so the old man had called her) among his downy young eaglets, he flew away. The eaglets naturally were rather surprised at this strange animal, so suddenly popped down in their midst, but instead of beginning to eat her, as their father expected, they nestled up close to her and spread out their tiny wings to shield her from the sun.

Now, in the depths of the forest where the eagle had built his nest, there ran a stream whose waters were poisonous, and on the banks of this stream dwelt a horrible lindworm with seven heads. The lindworm had often watched the eagle flying about the top of the tree, carrying food to his young ones and, accordingly, he watched carefully for the moment when the eaglets began to try their wings and to fly away from the nest. Of course, if the eagle himself was there to protect them even the lindworm, big and strong as he was, knew that he could do nothing; but when he was absent, any little eaglets who ventured too near the ground would be sure to disappear down the monster's throat. Their brothers, who had been left behind as too young and weak to see the world, knew nothing of all this, but supposed their turn would soon come to see the world also. And in a few days their eyes, too, opened and their wings flapped impatiently, and they longed to fly away above the waving tree-tops to mountain and the bright sun beyond. But that very midnight the lindworm, who was hungry and could not wait for his supper, came out of the brook with a rushing noise, and made straight for the tree. Two eyes of flame came creeping nearer, nearer, and two fiery tongues were stretching themselves out closer, closer, to the little birds who were trembling and shuddering in the farthest corner of the nest. But just as the tongues had almost reached them, the lindworm gave a fearful cry, and turned and fell backwards. Then came the sound of battle from the ground below, and the tree shook, though there was no wind, and roars and snarls mixed together, till the eaglets felt more frightened than ever, and thought their last hour had come. Only Wildrose was undisturbed, and slept sweetly through it all.

In the morning the eagle returned and saw traces of a fight below the tree, and here and there a handful of yellow mane lying about, and here and there a hard scaly substance; when he saw that he rejoiced greatly, and hastened to the nest.

'Who has slain the lindworm?' he asked of his children; there were so many that he did not at first miss the two which the lindworm had eaten. But the eaglets answered that they could not tell, only that they had been in danger of their lives, and at the last moment they had been delivered. Then the sunbeam had struggled through the thick branches and caught Wildrose's golden hair as she lay curled up in the corner, and the eagle wondered, as he looked, whether the little girl had brought him luck, and it was her magic which had killed his enemy.

'Children,' he said, 'I brought her here for your dinner, and you have not touched her; what is the meaning of this?' But the eaglets did not answer, and Wildrose opened her eyes, and seemed seven times lovelier than before.

From that day Wildrose lived like a little princess. The eagle flew about the wood and collected the softest, greenest moss he could find to make her a bed, and then he picked with his beak all the brightest and prettiest flowers in the fields or on the mountains to decorate it. So cleverly did he manage it that there was not a fairy in the whole of the forest who would not have been pleased to sleep there, rocked to and fro by the breeze on the treetops. And when the little ones were able to fly from their nest he taught them where to look for the fruits and berries which she loved.

So the time passed by, and with each year Wildrose grew taller and more beautiful, and she lived happily in her nest and never wanted to go out of it, only standing at the edge in the sunset, and looking upon the beautiful world.

For company she had all the birds in the forest, who came and talked to her, and for playthings the strange flowers which they brought her from far, and the butterflies which danced with her. And so the days slipped away, and she was fourteen years old.

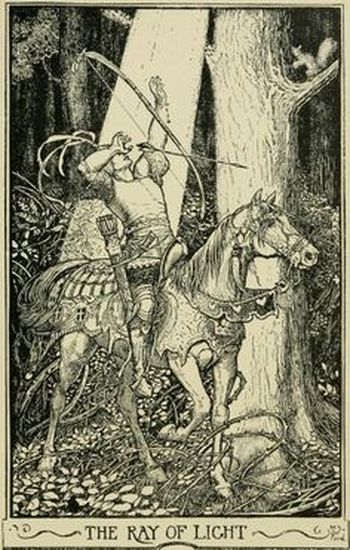

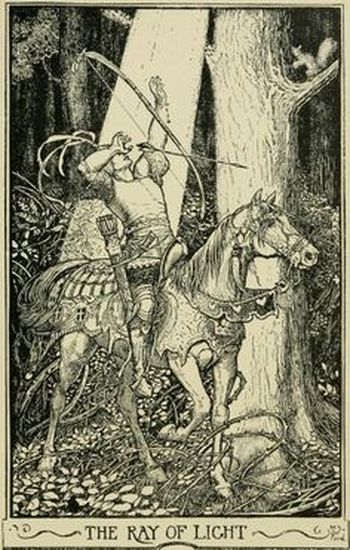

One morning the emperor's son went out to hunt, and he had not ridden far, before a deer started from under a grove of trees, and ran before him. The prince instantly gave chase, and where the stag led he followed, till at length he found himself in the depths of the forest, where no man before had trod.

The trees were so thick and the wood so dark, that he paused for a moment and listened, straining his ears to catch some sound to break a silence which almost frightened him. But nothing came, not even the baying of a hound or the note of a horn. He stood still, and wondered if he should go on, when, on looking up, a stream of light seemed to flow from the top of a tall tree. In its rays he could see the nest with the young eaglets, who were watching him over the side. The prince fitted an arrow into his bow and took his aim, but, before he could let fly, another ray of light dazzled him; so brilliant was it, that his bow dropped, and he covered his face with his hands. When at last he ventured to peep, Wildrose, with her golden hair flowing round her, was looking at him. This was the first time she had seen a man.

'Tell me how I can reach you?' cried he; but Wildrose smiled and shook her head, and sat down quietly.

The prince saw that it was no use, and turned and made his way out of the forest. But he might as well have stayed there, for any good he was to his father, so full was his heart of longing for Wildrose. Twice he returned to the forest in the hopes of finding her, but this time fortune failed him, and he went home as sad as ever.

At length the emperor, who could not think what had caused this change, sent for his son and asked him what was the matter. Then the prince confessed that the image of Wildrose filled his soul, and that he would never be happy without her. At first the emperor felt rather distressed. He doubted whether a girl from a tree top would make a good empress; but he loved his son so much that he promised to do all he could to find her. So the next morning heralds were sent forth throughout the whole land to inquire if anyone knew where a maiden could be found who lived in a forest on the top of a tree, and to promise great riches and a place at court to any person who should find her. But nobody knew. All the girls in the kingdom had their homes on the ground, and laughed at the notion of being brought up in a tree. 'A nice kind of empress she would make,' they said, as the emperor had done, tossing their heads with disdain; for, having read many books, they guessed what she was wanted for.

The heralds were almost in despair, when an old woman stepped out of the crowd and came and spoke to them. She was not only very old, but she was very ugly, with a hump on her back and a bald head, and when the heralds saw her they broke into rude laughter. 'I can show you the maiden who lives in the tree-top,' she said, but they only laughed the more loudly.

'Get away, old witch!' they cried, 'you will bring us bad luck'; but the old woman stood firm, and declared that she alone knew where to find the maiden.

'Go with her,' said the eldest of the heralds at last. 'The emperor's orders are clear, that whoever knew anything of the maiden was to come at once to court. Put her in the coach and take her with us.'

So in this fashion the old woman was brought to court.

'You have declared that you can bring hither the maiden from the wood?' said the emperor, who was seated on his throne.

'Yes, your Majesty, and I will keep my word,' said she.

'Then bring her at once,' said the emperor.

'Give me first a kettle and a tripod,' asked the old w omen, and the emperor ordered them to be brought instantly. The old woman picked them up, and tucking them under her arm went on her way, keeping at a little distance behind the royal huntsmen, who in their turn followed the prince.

Oh, what a noise that old woman made as she walked along! She chattered to herself so fast and clattered her kettle so loudly that you would have thought that a whole campful of gipsies must be coming round the next corner. But when they reached the forest, she bade them all wait outside, and entered the dark wood by herself.

She stopped underneath the tree where the maiden dwelt and, gathering some dry sticks, kindled a fire. Next, she placed the tripod over it, and the kettle on top. But something was the matter with the kettle. As fast as the old woman put it where it was to stand, that kettle was sure to roll off, falling to the ground with a crash.

It really seemed bewitched, and no one knows what might have happened if Wildrose, who had been all the time peeping out of her nest, had not lost patience at the old woman's stupidity, and cried out: 'The tripod won't stand on that hill, you must move it!'

'But where am I to move it to, my child?' asked the old woman, looking up to the nest, and at the same moment trying to steady the kettle with one hand and the tripod with the other.

'Didn't I tell you that it was no good doing that,' said Wildrose, more impatiently than before. 'Make a fire near a tree and hang the kettle from one of the branches.'

The old woman took the kettle and hung it on a little twig, which broke at once, and the kettle fell to the ground.

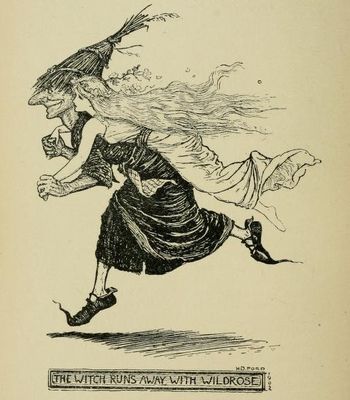

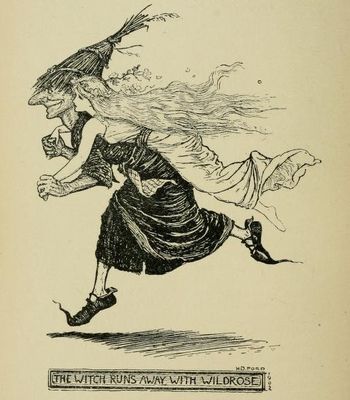

'If you would only show me how to do it, perhaps I should understand,' said she.

Quick as thought, the maiden slid down the smooth trunk of the tree, and stood beside the stupid old woman, to teach her how things ought to be done. But in an instant the old woman had caught up the girl and swung her over her shoulders, and was running as fast as she could go to the edge of the forest, where she had left the prince. When he saw them coming he rushed eagerly to meet them, and he took the maiden in his arms and kissed her tenderly before them all. Then a golden dress was put on her, and pearls were twined in her hair, and she took her seat in the emperor's carriage which was drawn by six of the whitest horses in the world, and they carried her, without stopping to draw breath, to the gates of the palace. And in three days the wedding was celebrated, and the wedding feast was held, and everyone who saw the bride declared that if anybody wanted a perfect wife they must go to seek her on top of a tree.

Adapted from the Roumanian.

La piccola Rosacanina

C’erano una volta le cose che sono accadute in questa storia, e se non fossero accadute, allora questa storia non sarebbe mai stata raccontata. Però c’era anche un tempo in cui lupi e agnelli giacevano pacificamente insieme in una stalla, e i pastori pranzavano con re e regine su sponde erbose.

C’era una volta, dunque, miei cari e buoni bambini, un uomo che viveva lì. Dovete sapere che quest’uomo aveva davvero cent’anni, se non almeno venti di più. E anche sua moglie era così vecchia che non saprei dirvi quanto; qualcuno diceva che fosse vecchia come la stessa dea Venere. Erano stati felici per tutti quegli anni, ma lo sarebbero stati ancora di più se avessero avuto dei bambini; sebbene fossero vecchi, non si erano mai rassegnati a farne a meno e spesso sedevano accanto al fuoco e parlavano di come avrebbero allevato i loro bambini se solo ne avessero avuti in casa.

Un giorno il vecchio sembrava più triste e pensieroso del solito e alla fine disse alla moglie: “Ascoltami, vecchia mia!”

”Che cosa vuoi?” disse lei.

”Dammi un po’ delle monete del forziere, perché sto per andare a fare un lungo viaggio – intorno al mondo – per vedere se mi riesca di trovare un bambino; mi fa male il cuore al pensiero che dopo la mia morte la casa cadrà nelle mani di sconosciuti. Lascia che ti dica una cosa: finché non avrò trovato un bambino, non tornerò di nuovo a casa.”

Così il vecchio prese una borsa e la riempì di cibo e di denaro e, gettandosela sulle spalle, disse addio alla moglie.

Per molto tempo vagò, e vagò e vagò, ma non vide nessun bambino; una mattina il suo vagabondare lo condusse in una foresta così fitta che la luce non poteva filtrare attraverso i rami. Il vecchio si fermò vedendo un luogo così spaventoso e dapprima ebbe paura di entrarvi; ma si rammentò del proverbio che diceva: ‘Accade ciò che non ti aspetti’ e forse in mezzo a quell’oscuro luogo avrebbe trovato il bambino che stava cercando. Così raccogliendo tutto il coraggio vi si infilò deciso.

Non so dirvi quanto dovette camminare là, quando infine giunse all’ingresso di una caverna in cui le tenebre sembravano cento volte più fitte che nella foresta stessa. Si fermò di nuovo, ma sentiva come se qualcosa lo spingesse ad entrare e vi penetrò con il batticuore.

Per alcuni minuti il silenzio e le tenebre lo atterrirono tanto che s’immobilizzò dove si trovava, non osando muovere un passo. Poi fece un grande sforzo e avanzò di qualche passo; improvvisamente, in lontananza davanti a lui, vide il baluginio di una luce. La vista lo rincuorò e di diresse verso quei deboli raggi finché poté vedere seduto un vecchio eremita con una lunga barba bianca.

L’eremita non sentì avvicinarsi il visitatore, o finse così, perché non vi badò e continuò a leggere il proprio libro. Dopo aver atteso pazientemente per un po’, il vecchio cadde sulle ginocchia e disse. “Buongiorno, venerabile padre!” ma sembrò che avesse parlato a un sasso. “Buongiorno, venerabile padre.” disse un po’ più forte e stavolta l’eremita gli fece cenno di avvicinarsi. “Figlio mio, “ sussurrò con una voce che risonò nella caverna, “che cosa ti conduce in questo luogo buio e lugubre? Sono passati cento anni da quando i miei occhi si sono posati sul volto di un uomo e non pensavo ne avrei visto di nuovo un altro.”

”È stata la mia infelicità a condurmi qui,” rispose il vecchio, “Non ho figli e mia moglie ed io ne abbiamo desiderato uno per tutta la vita. Così ho lasciato la mia casa e sono andato per il mondo, sperando che da qualche parte avrei trovato ciò che sto cercando.”

Allora l’eremita raccolse una mela da terra e gliela diede, dicendo: “Mangia metà di questa mela e dai la rimanenza a tua moglie, e metti fine al tuo vagabondaggio per il mondo.”

Il vecchio si chino e baciò i piedi dell’eremita per la gran gioia, poi uscì dalla caverna. Riprese la strada attraverso la foresta il più rapidamente gli consentirono le tenebre e infine giunse presso prati fioriti che lo abbagliarono con il loro splendore. Improvvisamente fu preso da un’intensa sete, come se gli andasse a fuoco la gola. Cerco intorno un ruscello, ma non ne vide nessuno, e la sua lingua si faceva sempre più arida. Infine lo sguardo gli cadde sulla mela, che fino a quel momento aveva stretta in mano, e per la sete dimenticò ciò che gli aveva detto l’eremita; invece di mangiarne solo una parte, mangiò anche quella della moglie e poi andò a dormire.

Quando si svegliò, vide qualcosa di strano riva poco lontana, tra lunghe macchie di rose rosa. Il vecchio si alzò, si stropicciò gli occhi e andò a vedere che cosa fosse quando, con grande sorpresa e gioia, si rivelò essere una bambina di circa due anni, con la carnagione bianca e rosea come le rose vicino a lei. La prese dolcemente tra le braccia, ma lei non parve affatto spaventata, si muoveva ed emetteva gridolini di gioia; il vecchio la avvolse nel mantello e tornò a casa con la maggior velocità che gli permettevano le gambe .

Quando furono vicini alla casetta in cui vivevano, depose la bambina in un secchio vicino alla porta e corse in casa, gridando: “Sbrigati, moglie, sbrigati perché ti ho portato una figlia con i capelli come l’oro e gli occhi come stelle!”

A questa meravigliosa notizia la vecchia corse dabbasso, quasi cadendo per la smania di vedere quel tesoro; ma quando il marito la condusse al secchio, era perfettamente vuoto! Il vecchio era fuori di se per la paura mentre sua moglie sedette e singhiozzo di dolore e di delusione. Non c’era luogo nei dintorni dove non cercassero, pensando che per qualche motivo la bambina fosse uscita dal secchio e si fosse nascosta per gioco; ma la piccola non era da nessuna parte e non c’erano tracce di lei.

”Dove può essere?” gemette disperato il vecchio. “Oh, perché l’ho lasciata, anche se solo per un momento? L’avranno rapita le fate o l’avrà portata via qualche animale selvaggio?” e continuarono a cercare dappertutto; ma non incontrarono né fate né animali selvaggi, e con il cuore affranto alla fine rinunciarono e tornarono tristemente a casa.

Che ne era stato della bambina? Ebbene, trovandosi da sola in un luogo strano, aveva incominciato a piangere di paura e un’aquila che volava da quelle parti l’aveva sentita ed era andata a vedere da dove venisse il rumore. Quando scorse la grassottella creatura bianca e rosea, pensò ai piccoli affamati nel nido e, scendendo in picchiata, la afferrò con gli artigli e volò con lei oltre le cime degli alberi. In pochi minuti raggiunse quello su cui aveva costruito il nido e, lasciando Rosacanina (perché così il vecchio l’aveva chiamata) tra i propri morbidi aquilotti, volò via. Gli aquilotti naturalmente furono piuttosto sorpresi da quello strano animale, capitato così in mezzo a loro, ma invece di cominciare a mangiarselo, come si aspettava il padre, si accoccolarono vicino a lei e spiegarono le alucce per ripararla dal sole.

Dovete sapere che nel folto della foresta in cui l’aquila aveva costruito il nido, scorreva un ruscello le cui acque erano velenose e sulle rive di questo ruscello abitava un orribile drago con sette teste. Il drago aveva visto spesso l’aquila volare nei pressi delle cime degli alberi, portando cibo ai piccoli, e , di conseguenza, stava attento al momento in cui gli aquilotti avrebbero cominciato a provare le ali e a volare via dal nido. Naturalmente se l’aquila stessa era lì era li a proteggerli, perfino il drago, grande e grosso com’era, sapeva che non avrebbe potuto fare nulla; ma quando non c’era, il primo aquilotto che si era avventurato vicino al terreno era di certo sparito tra le fauci del mostro. I suoi fratelli, che erano rimasti indietro perché ancora troppo giovani e deboli per affrontare il mondo, non sapevano nulla di tutto ciò e pensavano che presto anche loro sarebbero andati a scoprire il mondo. E in pochi giorni anche i loro occhi si aprirono e le loro ali sbatterono con impazienza, e desiderarono volare via dalle ondeggianti cime degli alberi verso le montagne e il sole luminoso al di là. Ma proprio a mezzanotte il drago, che era affamato non voleva più aspettare per cenare, uscì dal ruscello con un rapido rumore e puntò all’albero. Due occhi di fuoco scintillavano sempre più vicino e due lingue si spingevano sempre più addosso agli uccellini che stavano tremando e rabbrividendo nel punto più lontano del nido. Proprio mentre le lingue li avevano quasi raggiunti, il drago lanciò un terribile grido, poi si voltò e cadde all’indietro. Poi ci fu un rumore di battaglia che giungeva dal terreno sottostante e gli alberi si scossero, sebbene non vi fosse vento, e si mescolarono ruggiti e ringhi tantoché gli aquilotti si spaventarono più che mai e temettero fosse giunta la loro ora. Solo Rosacanina era tranquilla e dormiva soavemente in mezzo a tutto ciò.

La mattina l’aquila tornò e vide tracce di una lotta sotto l’albero e sparse qui e là manciate di criniera gialla e di squame; quando vide ciò, si rallegrò molto e si affrettò verso il nido.

”Chi ha ucciso il drago?” chiese ai piccoli; ce n’erano così tanti che dapprima non si avvide della perdita dei due che il drago aveva mangiato. Gli aquilotti risposero che non avrebbero saputo dirlo, a parte che le loro vite erano state in pericolo e che all’ultimo momento erano stati liberati. Allora un raggio di sole si fece strada tra i fitti rami e colpì i capelli d’oro di Rosacanina mentre era raggomitolata nell’angolo e l’aquila si vedendola, vedendola, se la bambina gli avesse portato fortuna e fosse la sua magia ad aver ucciso il nemico. Così disse: “Piccoli miei, ve l’ho portata qui come cena e voi non l’avete toccata; per quale ragione?” ma gli aquilotti non risposero e Rosacanina aprì gli occhi, sembrando sette volte più bella di prima. Da quel giorno Rosacanina visse come una principessa. L’aquila volava per la foresta e raccoglieva il muschio più soffice e più verde che potesse trovare per farle un letto, poi coglieva con il becco i fiori più belli e sgargianti dei prati o delle montagne per decorarlo. E fu così abile nel farlo che non ci sarebbe stata una fata in tutta la foresta che non sarebbe stata contenta di dormire lì, cullata dalla brezza culla cima dell’albero. E quando i piccoli furono in grado di volare via dal nido, insegnò loro dove trovare i frutti e le bacche che le piacevano.

Così passò il tempo e, anno dopo anno, Rosacanina diventava più alta e più bella, viveva felicemente nel nido e non voleva mai lasciarlo, affacciandosi al bordo solo al tramonto per ammirare il bellissimo mondo.

Come compagni aveva gli uccelli della foresta, che venivano a parlare con lei, e come giocattoli i fiori strani che le portavano da lontano e le farfalle che danzavano con lei. E così i giorni scivolavano via e compì quattordici anni.

Una mattina il figlio dell’imperatore andò a caccia e non dovette allontanarsi molto prima che un cervo sbucasse da un boschetto di alberi e gli corresse davanti. Immediatamente il principe lo inseguì, e gli andò dietro dove lo conduceva finché alla fine si trovò nel folto della foresta, dove mai nessun uomo prima aveva camminato.

Gli alberi erano così fitti e la foresta così oscura che si fermò per un momento ad ascoltare, tendendo l’orecchio per cogliere qualsiasi rumore che rompesse quel silenzio che gli faceva abbastanza paura. M non sentì nulla, né l’abbaiare del cane o le note del corno da caccia. Si soffermò ancora, chiedendosi dove sarebbe potuto andare, quando, guardando in su, gli sembrò che una lama di luce provenisse dalla cima di un alto albero. Tra quei raggi poté vedere il nido con gli aquilotti, che lo stavano osservando dal bordo. Il principe incoccò una freccia sull’arco e prese la mira, ma, prima che potesse scoccarla, un altro raggio di luce lo abbagliò; era così fulgido che l’arco gli cadde e si coprì il viso con le mani. Quando infine si azzardò a sbirciare, Rosacanina lo stava osservando con i capelli come l’oro che ondeggiavano. Era la prima volta in cui vedeva un uomo.

”Dimmi, come posso raggiungerti?” gridò lui, ma Rosacanina sorrise e scosse la testa, sedendosi tranquillamente.

Il principe vide che era tutto inutile, si voltò e riprese la strada nella foresta. Ma sarebbe voluto restare lì perché, per quanto volesse molto bene al padre, il suo cuore traboccava di desiderio per Rosacanina. Tornò due volte nella foresta con la speranza di trovarla, ma stavolta la fortuna non lo assistette e tornò a casa più triste che mai.

Infine l’imperatore, che non immaginava che cosa avesse potuto provocare un tale cambiamento, mandò a chiamare il figlio e gliene chiese la ragione. Allora il principe confessò che l’immagine di Rosacanina gli colmava l’anima e che non sarebbe mai stato felice senza di lei. Dapprima l’imperatore fu abbastanza afflitto. Dubitava che una ragazza proveniente dalla cima di un albero sarebbe stata una buona imperatrice; tuttavia amava tanto suo figlio che gli promise di fare di tutto per trovarla. Così il mattino seguente gli araldi furono mandati per tutto il regno a chiedere se qualcuno sapesse dove si potesse trovare una ragazza che viveva nella foresta sulla cima di un albero, e a promettere grandi ricchezze e un posto a corte a chiunque l’avesse trovata. Ma nessuno lo sapeva. Tutte le ragazze del regno avevano casa sul terreno e ridevano all’idea di essere allevate su un albero. “Che razza di imperatrice diventerebbe.” Dicevano, come già aveva fatto l’imperatore, scuotendo le teste con sdegno perché, avendo letto molti libri, ritenevano che la cercassero per questo motivo.

Gli araldi era quasi alla disperazione quando una vecchia si fece largo tra la folla e si rivolse loro. Non solo era molto vecchia, ma anche assai brutta, con una gobba sulla schiena e la testa pelata, e quando gli araldi la videro, scoppiarono in una risata insolente. “Posso mostrarvi la ragazza che vive in cima all’albero”, disse lei, ma essi risero ancora più forte.

”Sparisci, vecchia strega!” gridarono, “ci porti sfortuna.” Ma la vecchia tenne duro e dichiarò di essere l’unica a sapere dove trovare la ragazza.

”Vai con lei,” disse infine l’araldo più anziano al più giovane. “Gli ordini dell’imperatore sono chiari, chiunque sappia qualcosa della ragazza deve essere condotto subito a corte. Falla salire in carrozza e portiamola con noi.”

Così la vecchia fu condotta a corte in quel modo.

”Hai dichiarato di poter portare qui dalla foresta la ragazza?” disse l’imperatore, seduto sul trono.

”Sì, Vostra maestà, avete la mia parola.” disse lei.

”Allora portala qui subito.” disse l’imperatore.

”Prima datemi un pentolino e un treppiede,” disse la vecchia, e l’imperatore ordinò che le fossero portati immediatamente. La vecchia li prese e, mettendoseli sotto braccio, andò per la propria strada, tenendo a breve distanza dietro i cacciatori reali, i quali a loro volta seguivano il principe.

Oh, quanto rumore fece la vecchia mentre continuava a camminare! Parlava tra sé così velocemente e sbatteva il pentolino così rumorosamente che si sarebbe potuto pensare che un intero accampamento di zingari dovesse sbucare dal primo angolo. Ma quando ebbero raggiunto la foresta, ordinò loro di aspettare fuori ed entrò da sola nella buia foresta.

Si fermò sotto l’albero su cui abitava la ragazza e, raccogliendo alcuni rametti secchi, accese un fuoco. Poi vi pose sopra il treppiedi e mise in cima il pentolino. Ma qualcosa non andava con il pentolino. Per quanto la vecchia lo mettesse rapidamente dov’era, il pentolino cadeva, crollando a terra con gran rumore.

Sembrava stregato e nessuno sapeva che cosa sarebbe potuto accadere se Rosacanina, che per tutto il tempo aveva spiato dal nido, non avesse perso la pazienza per la stupidità della vecchia e gridatole: “Il treppiedi non può reggersi sul pendio, devi spostarlo!”

”Ma dove devo spostarlo, figlia mia?” chiese la vecchia, guardando su verso il nido e nello stesso momento tentando di reggere il pentolino con una mano e il treppiedi con l’altra.

”Non ti dico che non va bene farlo,” disse Rosacanina più impaziente di prima. “Accendi il fuoco vicino all’albero e appendi il pentolino a uno dei rami.”

La vecchia prese il pentolino e lo appese a un ramoscello, che si ruppe subito e il pentolini cadde a terra.

”Se solo tu mi mostrassi come fare, forse capirei.” disse la vecchia.

Rapida come il pensiero, la ragazza scivolò lungo il tronco dell’albero e si fermò accanto alla vecchia stupida, per insegnarle come fare. Ma in un attimo la vecchia afferrò la ragazza, se la mise in spalla e orse più in fretta che poté al limitare della foresta, dove aveva lasciato il principe. Quando le vide, si precipitò con ardore a incontrarle; prese fra le braccia la ragazza e la baciò teneramente davanti a tutti. Le fu fatto indossare un abito d’oro, le acconciarono i capelli con perle e prese posto nella carrozza dell’imperatore che era trainata dai sei cavalli più bianchi del mondo, che la portarono via, senza fermarsi a riprendere fiato, fino ai cancelli del palazzo. In tre furono celebrate le nozze e si tenne la festa nuziale; ognuno che vide la sposa dichiarò che se qualcuno voleva una moglie perfetta, doveva andare a prendersela in cima a un albero.

Adattamento di una fiaba rumena

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)