The Gold-Bearded Man

(MP3-20'43'')

Once upon a time there lived a great king who had a wife and one son whom he loved very much. The boy was still young when, one day, the king said to his wife: 'I feel that the hour of my death draws near, and I want you to promise that you will never take another husband but will give up your life to the care of our son.'

The queen burst into tears at these words, and sobbed out that she would never, never marry again, and that her son's welfare should be her first thought as long as she lived. Her promise comforted the troubled heart of the king, and a few days after he died, at peace with himself and with the world.

But no sooner was the breath out of his body, than the queen said to herself, 'To promise is one thing, and to keep is quite another.' And hardly was the last spadeful of earth flung over the coffin than she married a noble from a neighbouring country, and got him made king instead of the young prince. Her new husband was a cruel, wicked man, who treated his stepson very badly, and gave him scarcely anything to eat, and only rags to wear; and he would certainly have killed the boy but for fear of the people.

Now by the palace grounds there ran a brook, but instead of being a water-brook it was a milk-brook, and both rich and poor flocked to it daily and drew as much milk as they chose. The first thing the new king did when he was seated on the throne, was to forbid anyone to go near the brook, on pain of being seized by the watchmen. And this was purely spite, for there was plenty of milk for everybody.

For some days no one dared venture near the banks of the stream, but at length some of the watchmen noticed that early in the mornings, just at dawn, a man with a gold beard came down to the brook with a pail, which he filled up to the brim with milk, and then vanished like smoke before they could get near enough to see who he was. So they went and told the king what they had seen.

At first the king would not believe their story, but as they persisted it was quite true, he said that he would go and watch the stream that night himself. With the earliest streaks of dawn the gold-bearded man appeared, and filled his pail as before. Then in an instant he had vanished, as if the earth had swallowed him up.

The king stood staring with eyes and mouth open at the place where the man had disappeared. He had never seen him before, that was certain; but what mattered much more was how to catch him, and what should be done with him when he was caught? He would have a cage built as a prison for him, and everyone would talk of it, for in other countries thieves were put in prison, and it was long indeed since any king had used a cage. It was all very well to plan, and even to station a watchman behind every bush, but it was of no use, for the man was never caught. They would creep up to him softly on the grass, as he was stooping to fill his pail, and just as they stretched out their hands to seize him, he vanished before their eyes. Time after time this happened, till the king grew mad with rage, and offered a large reward to anyone who could tell him how to capture his enemy.

The first person that came with a scheme was an old soldier who promised the king that if he would only put some bread and bacon and a flask of wine on the bank of the stream, the gold-bearded man would be sure to eat and drink, and they could shake some powder into the wine, which would send him to sleep at once. After that there was nothing to do but to shut him in the cage.

This idea pleased the king, and he ordered bread and bacon and a flask of drugged wine to be placed on the bank of the stream, and the watchers to be redoubled. Then, full of hope, he awaited the result.

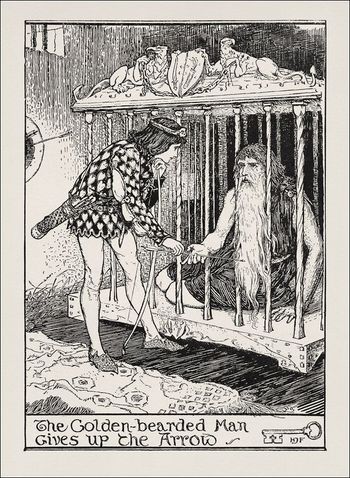

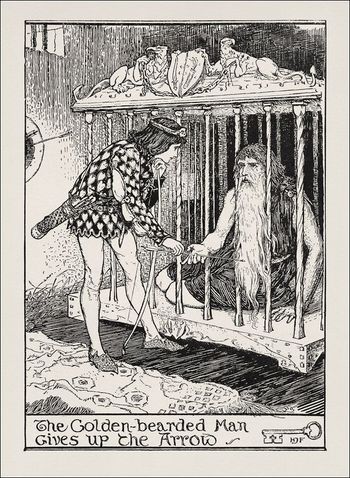

Everything turned out just as the soldier had said. Early next morning the gold-bearded man came down to the brook, ate, drank, and fell sound asleep, so that the watchers easily bound him, and carried him off to the palace. In a moment the king had him fast in the golden cage, and showed him, with ferocious joy, to the strangers who were visiting his court. The poor captive, when he awoke from his drunken sleep, tried to talk to them, but no one would listen to him, so he shut himself up altogether, and the people who came to stare took him for a dumb man of the woods. He wept and moaned to himself all day, and would hardly touch food, though, in dread that he should die and escape his tormentors, the king ordered his head cook to send him dishes from the royal table.

The gold-bearded man had been in captivity about a month, when the king was forced to make war upon a neighbouring country, and left the palace, to take command of his army. But before he went he called his stepson to him and said:

'Listen, boy, to what I tell you. While I am away I trust the care of my prisoner to you. See that he has plenty to eat and drink, but be careful that he does not escape, or even walk about the room. If I return and find him gone, you will pay for it by a terrible death.'

The young prince was thankful that his stepfather was going to the war, and secretly hoped he might never come back. Directly he had ridden off the boy went to the room where the cage was kept, and never left it night and day. He even played his games beside it.

One day he was shooting at a mark with a silver bow; one of his arrows fell into the golden cage.

'Please give me my arrow,' said the prince, running up to him; but the gold-bearded man answered:

'No, I shall not give it to you unless you let me out of my cage.'

'I may not let you out,' replied the boy, 'for if I do my stepfather says that I shall have to die a horrible death when he returns from the war. My arrow can be of no use to you, so give it to me.'

The man handed the arrow through the bars, but when he had done so he begged harder than ever that the prince would open the door and set him free. Indeed, he prayed so earnestly that the prince's heart was touched, for he was a tender-hearted boy who pitied the sorrows of other people. So he shot back the bolt, and the gold-bearded man stepped out into the world.

'I will repay you a thousand fold for that good deed.' said the man, and then he vanished. The prince began to think what he should say to the king when he came back; then he wondered whether it would be wise to wait for his stepfather's return and run the risk of the dreadful death which had been promised him. 'No,' he said to himself, 'I am afraid to stay. Perhaps the world will be kinder to me than he has been.'

Unseen he stole out when twilight fell, and for many days he wandered over mountains and through forests and valleys without knowing where he was going or what he should do. He had only the berries for food, when, one morning, he saw a wood-pigeon sitting on a bough. In an instant he had fitted an arrow to his bow, and was taking aim at the bird, thinking what a good meal he would make off him, when his weapon fell to the ground at the sound of the pigeon's voice:

'Do not shoot, I implore you, noble prince! I have two little sons at home, and they will die of hunger if I am not there to bring them food.'

And the young prince had pity, and unstrung his bow.

'Oh, prince, I will repay your deed of mercy, said the grateful wood-pigeon.

'Poor thing! how can you repay me?' asked the prince.

'You have forgotten,' answered the wood-pigeon, 'the proverb that runs, "mountain and mountain can never meet, but one living creature can always come across another."' The boy laughed at this speech and went his way.

By-and-by he reached the edge of a lake, and flying towards some rushes which grew near the shore he beheld a wild duck. Now, in the days that the king, his father, was alive, and he had everything to eat he could possibly wish for, the prince always had wild duck for his birthday dinner, so he quickly fitted an arrow to his bow and took a careful aim.

'Do not shoot, I pray you, noble prince!' cried the wild duck; 'I have two little sons at home; they will die of hunger if I am not there to bring them food.'

And the prince had pity, and let fall his arrow and unstrung his bow.

'Oh, prince! I will repay your deed of mercy,' exclaimed the grateful wild duck.

'You poor thing! how can you repay me?' asked the prince.

'You have forgotten,' answered the wild duck, 'the proverb that runs, "mountain and mountain can never meet, but one living creature can always come across another."' The boy laughed at this speech and went his way.

He had not wandered far from the shores of the lake, when he noticed a stork standing on one leg, and again he raised his bow and prepared to take aim.

'Do not shoot, I pray you, noble prince,' cried the stork; 'I have two little sons at home; they will die of hunger if I am not there to bring them food.'

Again the prince was filled with pity, and this time also he did not shoot.

'Oh, prince, I will repay your deed of mercy,' cried the stork.

'You poor stork! how can you repay me?' asked the prince.

'You have forgotten,' answered the stork, 'the proverb that runs, "mountain and mountain can never meet, but one living creature can always come across another."'

The boy laughed at hearing these words again, and walked slowly on. He had not gone far, when he fell in with two discharged soldiers.

'Where are you going, little brother?' asked one. 'I am seeking work,' answered the prince.

'So are we,' replied the soldier. 'We can all go together.'

The boy was glad of company and they went on, and on, and on, through seven kingdoms, without finding anything they were able to do. At length they reached a palace, and there was the king standing on the steps.

'You seem to be looking for something,' said he. 'It is work we want,' they all answered.

So the king told the soldiers that they might become his coachmen; but he made the boy his companion, and gave him rooms near his own. The soldiers were dreadfully angry when they heard this, for of course they did not know that the boy was really a prince; and they soon began to lay their heads together to plot his ruin.

Then they went to the king.

'Your Majesty,' they said, 'we think it our duty to tell you that your new companion has boasted to us that if he were only your steward he would not lose a single grain of corn out of the storehouses. Now, if your Majesty would give orders that a sack of wheat should be mixed with one of barley, and would send for the youth, and command him to separate the grains one from another, in two hours' time, you would soon see what his talk was worth.'

The king, who was weak, listened to what these wicked men had told him, and desired the prince to have the contents of the sack piled into two heaps by the time that he returned from his council. 'If you succeed,' he added, 'you shall be my steward, but if you fail, I will put you to death on the spot.'

The unfortunate prince declared that he had never made any such boast as was reported; but it was all in vain. The king did not believe him, and turning him into an empty room, bade his servants carry in the huge sack filled with wheat and barley, and scatter them in a heap on the floor.

The prince hardly knew where to begin, and indeed if he had had a thousand people to help him, and a week to do it in, he could never have finished his task. So he flung himself on the ground in despair, and covered his face with his hands.

While he lay thus, a wood-pigeon flew in through the window.

'Why are you weeping, noble prince?' asked the wood-pigeon.

'How can I help weeping at the task set me by the king. For he says, if I fail to do it, I shall die a horrible death.'

'Oh, there is really nothing to cry about,' answered the wood-pigeon soothingly. 'I am the king of the wood-pigeons, whose life you spared when you were hungry. And now I will repay my debt, as I promised.' So saying he flew out of the window, leaving the prince with some hope in his heart.

In a few minutes he returned, followed by a cloud of wood-pigeons, so dense that it seemed to fill the room. Their king showed them what they had to do, and they set to work so hard that the grain was sorted into two heaps long before the council was over. When the king came back he could not believe his eyes; but search as he might through the two heaps, he could not find any barley among the wheat, or any wheat amongst the barley. So he praised the prince for his industry and cleverness, and made him his steward at once.

This made the two soldiers more envious still, and they began to hatch another plot.

'Your Majesty,' they said to the king, one day, as he was standing on the steps of the palace, 'that fellow has been boasting again, that if he had the care of your treasures not so much as a gold pin should ever be lost. Put this vain fellow to the proof, we pray you, and throw the ring from the princess's finger into the brook, and bid him find it. We shall soon see what his talk is worth.'

And the foolish king listened to them, and ordered the prince to be brought before him.

'My son,' he said, 'I have heard that you have declared that if I made you keeper of my treasures you would never lose so much as a gold pin. Now, in order to prove the truth of your words, I am going to throw the ring from the princess's finger into the brook, and if you do not find it before I come back from council, you will have to die a horrible death.'

It was no use denying that he had said anything of the kind. The king did not believe him; in fact he paid no attention at all, and hurried off, leaving the poor boy speechless with despair in the corner. However, he soon remembered that though it was very unlikely that he should find the ring in the brook, it was impossible that he should find it by staying in the palace.

For some time the prince wandered up and down peering into the bottom of the stream, but though the water was very clear, nothing could he see of the ring. At length he gave it up in despair, and throwing himself down at the foot of the tree, he wept bitterly.

'What is the matter, dear prince?' said a voice just above him, and raising his head, he saw the wild duck.

'The king of this country declares I must die a horrible death if I cannot find the princess's ring which he has thrown into the brook,' answered the prince.

'Oh, you must not vex yourself about that, for I can help you,' replied the bird. 'I am the king of the wild ducks, whose life you spared, and now it is my turn to save yours.' Then he flew away, and in a few minutes a great flock of wild ducks were swimming all up and down the stream looking with all their might, and long before the king came back from his council there it was, safe on the grass beside the prince.

At this sight the king was yet more astonished at the cleverness of his steward, and at once promoted him to be the keeper of his jewels.

Now you would have thought that by this time the king would have been satisfied with the prince, and would have left him alone; but people's natures are very hard to change, and when the two envious soldiers came to him with a new falsehood, he was as ready to listen to them as before.

'Gracious Majesty,' said they, 'the youth whom you have made keeper of your jewels has declared to us that a child shall be born in the palace this night, which will be able to speak every language in the world and to play every instrument of music. Is he then become a prophet, or a magician, that he should know things which have not yet come to pass?'

At these words the king became more angry than ever. He had tried to learn magic himself, but somehow or other his spells would never work, and he was furious to hear that the prince claimed a power that he did not possess. Stammering with rage, he ordered the youth to be brought before him, and vowed that unless this miracle was accomplished he would have the prince dragged at a horse's tail until he was dead.

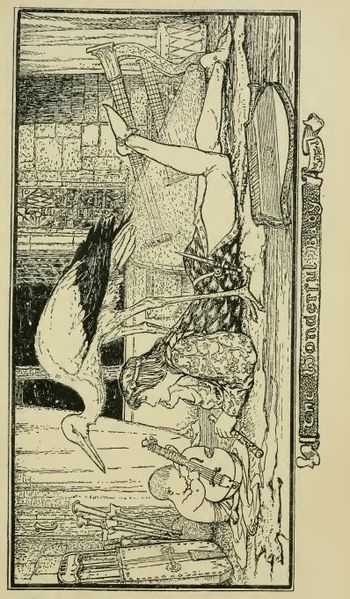

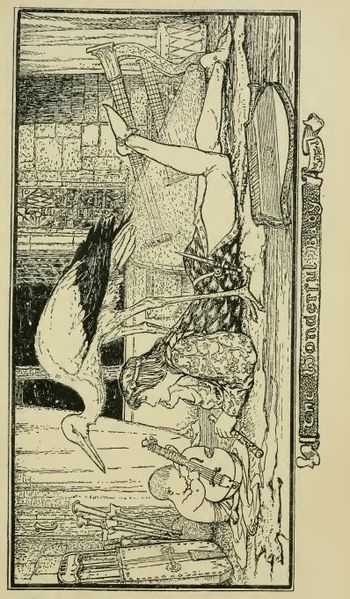

In spite of what the soldiers had said, the boy knew no more magic than the king did, and his task seemed more hopeless than before. He lay weeping in the chamber which he was forbidden to leave, when suddenly he heard a sharp tapping at the window, and, looking up, he beheld a stork.

'What makes you so sad, prince?' asked he.

'Someone has told the king that I have prophesied that a child shall be born this night in the palace, who can speak all the languages in the world and play every musical instrument. I am no magician to bring these things to pass, but he says that if it does not happen he will have me dragged through the city at a horse's tail till I die.'

'Do not trouble yourself,' answered the stork. 'I will manage to find such a child, for I am the king of the storks whose life you spared, and now I can repay you for it.'

The stork flew away and soon returned carrying in his beak a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes, and laid it down near a lute. In an instant the baby stretched out its little hands and began to play a tune so beautiful that even the prince forgot his sorrows as he listened. Then he was given a flute and a zither, but he was just as well able to draw music from them; and the prince, whose courage was gradually rising, spoke to him in all the languages he knew. The baby answered him in all, and no one could have told which was his native tongue!

The next morning the king went straight to the prince's room, and saw with his own eyes the wonders that baby could do. 'If your magic can produce such a baby,' he said, 'you must be greater than any wizard that ever lived, and shall have my daughter in marriage.' And, being a king, and therefore accustomed to have everything the moment he wanted it, he commanded the ceremony to be performed without delay, and a splendid feast to be made for the bride and bridegroom. When it was over, he said to the prince:

'Now that you are really my son, tell me by what arts you were able to fulfil the tasks I set you?'

'My noble father-in-law,' answered the prince, 'I am ignorant of all spells and arts. But somehow I have always managed to escape the death which has threatened me.' And he told the king how he had been forced to run away from his stepfather, and how he had spared the three birds, and had joined the two soldiers, who had from envy done their utmost to ruin him.

The king was rejoiced in his heart that his daughter had married a prince, and not a common man, and he chased the two soldiers away with whips, and told them that if they ever dared to show their faces across the borders of his kingdom, they should die the same death he had prepared for the prince.

From Ungarische Märchen.

L'uomo dalla barba d'oro

C’era una volta un grande re il quale aveva una moglie e un unico figlio che amava moltissimo. Il bambino era ancora piccolo quando un giorno il re disse alla moglie: “Credo che l’ora della mia morte si avvicini, e voglio che tu mi prometta che non prenderai mai un altro marito, ma dedicherai la tua vita ad avere cura di nostro figlio.”

A quelle parole la regina scoppiò in lacrime e singhiozzò che mai e poi mai si sarebbe sposata di nuovo, e che il benessere del figlio sarebbe stato il suo pensiero principale finché avesse avuto vita. La promessa consolò il cuore afflitto del re e pochi giorno egli morì, in pace con se stesso e con il mondo.

Ma aveva appena esalato l’ultimo respiro che la regina si disse: ‘Promettere è un conto, mantenere è un altro’. E l’ultima palata di terra era a malapena caduta sulla bara che lei si era già sposata con un nobile di un paese vicino e lo aveva fatto re al posto del giovane principe. Il nuovo marito era un uomo crudele e malvagio, che trattava assai male il figliastro e gli dava a malapena qualcosa da mangiare e solo stracci per vestirsi; certamente avrebbe ucciso il bambino, se non avesse avuto paura del popolo.

Dovete sapere che dai terreni del palazzo scorreva un ruscello, ma invece di essere d’acqua era di latte, e sia i ricchi che i poveri vi accorrevano ogni giorno e ne prendevano tanto latte quanto volevano. Quando fu assiso sul trono, la prima cosa che fece il nuovo re fu proibire a chiunque di avvicinarsi al ruscello, pena l’arresto da parte delle sentinelle. E ciò puramente un dispetto perché c’era abbondanza di latte per tutti.

Per un po’ di giorni nessuno osò avventurarsi presso le rive del ruscello, ma alla fine le sentinelle si accorsero che ogni mattina presto, proprio all’alba, un uomo con una barba d’oro scendeva al ruscello con un secchio, che riempiva di latte fino all’orlo e poi svaniva come fumo prima che essi potessero avvicinarsi abbastanza da vedere chi fosse. Così andarono dal re a riferirgli ciò che avevano visto.

Dapprima il re non volle credere alla loro storia, ma siccome insistevano che fosse vera, disse che lui stesso quella notte sarebbe andato a sorvegliare il ruscello. Alle prime luci dell’alba apparve l’uomo con la barba d’oro e riempì il secchio come aveva fatto prima. Poi in un attimo era svanito, come se la terra lo avesse inghiottito.

Il re rimase a fissare con gli occhi e la bocca spalancati il posto in cui l’uomo era scomparso. Non lo aveva mai visto prima, questo era certo; la cosa più importante era come catturarlo e che cosa fare di lui una volta catturato? Avrebbe fatto costruire una gabbia per lui come prigione e tutti ne avrebbero parlato, perché negli altri paesi i ladri venivano messi in prigione e era trascorso del tempo da quando un qualunque re aveva usato una gabbia. Fu organizzato tutto molto bene, persino collocare una sentinella dietro ogni cespuglio, ma fu vano perché l’uomo non venne mai catturato. Potevano strisciare cautamente nell’erba mentre era chino a riempire il secchio, e appena allungavano le mani per afferrarlo, svaniva sotto i loro occhi. Ciò accadde ripetutamente finché il re montò in collera e offrì una lauta ricompensa a chiunque gli avesse detto come catturare il nemico.

La prima persona che venne con un piano fu un vecchio soldato il quale promise al re che se avesse messo sulla sponda del ruscello solo un po’ di pane e di pancetta con un fiasco di vino, l’uomo dalla barba d’oro avrebbe di certo mangiato e bevuto, e loro avrebbero potuto versare una polverina nel vino così che cadesse subito addormentato. Dopo di che non ci sarebbe stato altro da fare che chiuderlo in gabbia.

Al re piacque questa idea e ordinò che pane e pancetta e un fiasco di vino drogato fossero posti sulla riva del ruscello e che le sentinelle fossero raddoppiate. Poi attese il risultato, pieno di speranza.

Tutto andò come aveva detto il soldato. La mattina presto l’uomo dalla barba d’oro scese al ruscello; mangiò e bevve, poi cadde addormentato così che le sentinelle poterono facilmente legarlo e portarlo a palazzo. In poco tempo il re lo aveva chiuso nella gabbia d’oro e lo esibiva con gioia feroce agli stranieri che venivano in visita a corte. Il povero prigioniero, quando si svegliò dal sonno dovuto all’ebbrezza, tentò di parlare con loro, ma nessuno voleva ascoltarlo così egli si chiuse in se stesso e la gente che veniva a vederlo lo scambiava per un ottuso uomo dei boschi. Lui piangeva e si lamentava tra sé tutto il giorno e a malapena toccava il cibo e nel timore che potesse morire e sfuggire ai suoi aguzzini, il re ordinò al capo cuoco di mandargli i cibi della tavola regale.

L’uomo dalla barba d’oro era prigioniero da un mese quando il re fu costretto a dichiarare guerra al paese vicino e a lasciare il palazzo per guidare l’esercito. Prima però chiamò il figliastro e gli disse:

”Ragazzo, ascolta ciò che ti dico. Mentre sono via, affido a te la cura del prigioniero. Controlla che abbia in abbondanza da mangiare e da bere, ma stai bene attento che non scappi o cammini per la stanza. Se al mio ritorno scoprirò che se n’è andato, pagherai con una morte terribile.”

Il giovane principe era riconoscente per il fatto che il patrigno stesse andando in guerra e sperava segretamente che non tornasse mai più. Appena se ne fu andato a cavallo, il ragazzo andò nella stanza in cui si trovava la gabbia e non la lasciò mai, giorno e notte. Giocava persino accanto a essa.

Un giorno stava tirando al bersaglio con delle frecce d’argento e una di esse cadde nella gabbia d’oro.

Correndogli vicino, il principe disse: “Per favore, dammi la mia freccia.” Ma l’uomo dalla barba d’oro rispose:

”No, non te la darò a meno che non mi liberi dalla gabbia.”

Il bambino rispose: “Non posso farti uscire perché, se lo facessi, il mio patrigno ha detto che subirei una morte terribile al suo ritorno dalla guerra. La mia freccia non ti può essere utile perciò ridammela.”

L’uomo porse la freccia tra le sbarre, ma quando l’ebbe fatto, lo implorò così intensamente che il principe aprì la porta e lo lasciò libero. In effetti lo aveva implorato così ardentemente che il cuore del principe ne era rimasto toccato perché era un bambino dal cuore tenero e aveva compassione dei dolori degli altri. Così tirò il catenaccio e l’uomo dalla barba d’oro se ne andò per il mondo.

”Ti ripagherò mille volte per questa buona azione.” Disse l’uomo e poi sparì. Il principe cominciò a pensare a ciò che avrebbe detto al re quando fosse tornato; poi si chiese se fosse saggio aspettare il ritorno del patrigno e correre il rischio di della morte spaventosa che gli aveva promesso. “No,” si disse, “ho paura di restare. Forse il mondo sarà più gentile con me di quanto lo sia stato lui.”

Al crepuscolo scivolò fuori inosservato e per molti giorni vagò sulle montagne e attraverso le foreste e le valli senza sapere dove stesse andando o che cosa stesse facendo. Aveva solo le bacche come cibo quando una mattina vide un colombaccio su un ramo. In un attimo incoccò la freccia sull’arco e stava mirando all’uccello, grato per il buon cibo che avrebbe avuto, quando l’arma gli cadde a terra al suono della voce del colombaccio.

”Non colpirmi, ti imploro, o nobile principe! Ho due figlioletti a casa e moriranno di fame e se non porterò loro del cibo.”

Il giovane principe si mosse a compassione e sfilò la freccia.

”Oh, principe, ti ricompenserò per questo atto di misericordia.“ disse il piccione riconoscente.

”Poverino! E come potrai ripagarmi?” chiese il principe.

Il piccione rispose: “Hai dimenticato il proverbio che dice ‘le montagne non si possono incontrare, ma ogni creatura vivente può sempre incontrarne un’altra.’” Il bambino rise a queste parole e riprese la strada.

Di lì a poco raggiunse la sponda di un lago e, andando verso alcuni giunchi che crescevano vicino alla spiaggia, vide un’anatra selvatica. Dovete sapere che nei giorni in cui il re suo padre era vivo e lui aveva da mangiare tutto ciò che potesse desiderare, il principe aveva sempre l’anatra selvatica per il suo pranzo di compleanno, così incoccò rapidamente una freccia sull’arco e prese la mira.

Non colpirmi, ti prego, nobile principe!” gridò l’anatra selvatica, “ho due figlioletti a casa e moriranno di fame se non porterò loro del cibo.”

Il principe ebbe compassione, lasciò cadere la freccia e allentò l’arco.

”Oh, principe! Ti ricompenserò per questo atto di Misericordia.” esclamò riconoscente l’anatra selvatica.

”Poverina! Come potrai ricompensarmi?” chiese il principe.

L’anatra selvatica rispose: “Hai dimenticato il proverbio che dice ‘le montagne non si possono incontrare, ma ogni creatura vivente può sempre incontrarne un’altra.’” Il bambino rise a queste parole e riprese la strada.

Non si era allontanato molto dalla riva del lago quando si accorse di una cicogna su una sola zampa e di nuovo incoccò la freccia e si preparò a prendere la mira.

”Non colpirmi, ti prego, nobile principe!” gridò la cicogna. “Ho due figlioletti a casa e moriranno di fame se non porterò loro del cibo.”

Di nuovo il principe fu mosso a compassione e anche stavolta non fece partire il colpo.

”Oh, principe! Ti ricompenserò per questo atto di Misericordia.” Gridò la cicogna.

”Povera cicogna! Come potrai ricompensarmi?” chiese il principe.

La cicogna rispose: “Hai dimenticato il proverbio che dice ‘le montagne non si possono incontrare, ma ogni creatura vivente può sempre incontrarne un’altra.’”

Il bambino rise nel sentire queste parole e se ne andò lentamente. Non era giunto molto lontano quando si si imbatté in due soldati congedati.

”Dove stai andando, fratellino?” chiese uno.

”Sto cercando lavoro.” rispose il principe.

Il soldato rispose: “Anche noi. Possiamo viaggiare tutti insieme.”

Il bambino fu contento della compagnia e se ne andarono; cammina cammina, attraversarono sette regni senza trovare nulla che fossero capaci di fare. Infine giunsero ad un palazzo e lì c’era il re in piedi sui gradini.

”Mi sembrate in cerca di qualcosa.” disse.

”Vogliamo un lavoro.” risposero tutti loro.

Allor ail re disse ai soldati che sarebbero potuti diventare i suoi cocchieri, ma ebbe compassione del bambino e gli diede una stanza vicino alla propria. I soldati si arrabbiarono molto nel sentire ciò perché ovviamente non sapevano che il bambino fosse in realtà un principe; così cominciarono presto a tramare insieme per provocare la sua rovina.

Allora andarono dal re.

”Vostra Maestà,” gli dissero, “riteniamo sia nostro dovere dirvi che il vostro nuovo compagno si è vantato con noi ce se solo fosse stato vostro amministratore, non avrebbe sprecato un solo chicco di granturco del vostro granaio. Se Vostra Maestà vorrà ordinare che sia mischiato un sacco di grano con uno di orzo e che sia mandato al ragazzo con l’ordine di separare i chicchi gli uni dagli altri in due ore, ben presto potrete vedere che valore abbiano le sue parole.”

Il re, che era debole, ascoltò ciò che gli avevano detto i due malvagi uomini e chiese che il principe ammassasse il contenuto di due sacchi in due mucchi nel tempo in cui lui avesse fatto ritorno dal consiglio. E aggiunse: “Se avrai successo, sarai il mio amministratore, ma se fallirai, ti manderò a morte su due piedi.”

Lo sfortunato principe dichiarò di non essersi mai vantato nel modo che gli era stato riferito, ma fu inutile. Il re non gli credette e, conducendolo in una stanza vuota, ordinò ai servi di portare dentro il grosso sacco pieno di grano e di orzo e di rovesciarlo in un mucchio sul pavimento.

Il principe sapeva a malapena da dove incominciare e seppure avesse avuto un migliaio di persone ad aiutarlo e una settimana per farlo, non avrebbe mai portato a termine il compito. Così si gettò disperato sul pavimento e si coprì il viso con le mani.

Mentre giaceva così, un colombaccio entrò volando attraverso la finestra.

”Perché stai piangendo, nobile principe?” chiese il colombaccio.

”Come posso fare a meno di piangere per il compito che mi ha assegnato il re. Perché ha detto che, se fallirò nel compierlo, mi condannerà a una morte orribile.”

”Oh, non c’è proprio nessun motive di piangere,” rispose il colombaccio rassicurante. “Io sono il re dei colombacci al quale hai risparmiato la vita quando eri affamato. Adesso ripagherò il mio debito, come ti avevo promesso.” E così dicendo, volò fuori dalla finestra, lasciando il principe con una certa speranza in cuore.

Tornò in pochi minuti, seguito da uno stormo di colombacci così fitto che sembrò riempire la stanza. Il re mostro loro che cosa dovessero fare e si misero al lavoro così duramente che i chicchi furono ammassati in due mucchi prima che il consiglio fosse terminato. Quando il re tornò, non poteva credere ai propri occhi, ma per quanto cercasse tra i due mucchi, non poté trovare un chicco di orzo nel grano o di grano tra l’orzo. Così elogiò il principe per la diligenza e l’abilità e lo fece subito suo amministratore.

Ciò rese I due soldati ancora più invidiosi e cominciarono ad architettare un altro piano.

”Vostra Maestà,” dissero al re un giorno in cui si trovava sui gradini del palazzo. “Il briccone si è vantato di nuovo che se avesse avuto la custodia del vostro tesoro, neppure uno spillo d’oro sarebbe mai stato smarrito. Mettete alla prova questo briccone vanitoso, ve ne preghiamo, e gettate l’anello della principessa in un ruscello, poi ordinategli di trovarlo. Vedremo presto che valore abbiano le sue parole.”

Lo sciocco re li ascoltò e ordinò che gli fosse condotto davanti il principe.

Gli disse: “Figlio mio, ho sentito dire che hai dichiarato che se fossi il custode dei miei tesori, non perderesti neppure uno spillo d’oro. Adesso, per provare la verità delle tue parole, il farò gettare l’anello della principessa nel ruscello e se non lo ritroverai prima che io torni dal consiglio, incontrerai una morte orribile.

A nulla servì negare di non aver mai detto nulla di simile. Il re non gli credette; infatti non gli prestò del tutto attenzione e corse via, lasciando il povero ragazzo in un angolo, senza parole per la disperazione. In ogni modo si rammentò ben presto che, sebbene sarebbe stato assai difficile trovare l’anello nel ruscello, sarebbe stato impossibile trovarlo restando a palazzo.

Per un po’ di tempo il principe vagò su e giù scrutando il fondo del ruscello, ma sebbene l’acqua fosse molto limpida, l’anello non si vedeva. Alla fine si abbandonò alla disperazione e, gettandosi ai piedi di un albero, pianse amaramente.

”Che succede, caro principe?” chiese una voce proprio sopra di lui e, alzando il capo, vide l’anatra selvatica.

Il re di questo paese ha dichiarato che subirò una morte orribile se non potrò ritrovare l’anello della principessa che lui ha gettato nel ruscello.” rispose il principe.

”Oh, non devi angustiarti per questo perché io posso aiutarti.” rispose l’anatra. “Sono il re delle anatre selvatiche, la cui vita hai risparmiato, e ora è il turno di salvarti.” Poi volò via e in pochi minuti un grande stormo di anatre selvatiche stava nuotando su e giù lungo il ruscello con tutte le proprie forze e, ben prima che il tornasse dal consiglio in cui si trovava, l’anello fu al sicuro sull’erba davanti al principe.

A questa vista il re rimase ancora più sbalordito per l’abilità del suo amministratore e lo promosse subito a custode dei gioielli.

Ora voi potreste pensare che a questo punto il re fosse soddisfatto del principe e lo avrebbe lasciato in pace; ma l’indole delle persone è assai difficile da comprendere e quando i due soldati invidiosi vennero da lui con una nuova menzogna, fu pronto a credere loro come prima.

Gli dissero: “Graziosa Maestà, il giovane che avete fatto custode dei vostri gioielli ci ha annunciato che stanotte a palazzo sarebbe nato un bambino capace di parlare tutte le lingue del mondo e di suonare qualsiasi strumento musicale. È dunque diventato un profeta o un mago, per poter sapere cose che non sono ancora accadute?”

A queste parole il re si arrabbiò più che mai. Aveva tentato egli stesso di imparare la magia, ma in un modo o nell’altro i suoi incantesimi non erano riusciti e era furioso nel sentire il principe pretendere di avere un potere che lui non possedeva. Farfugliando per la collera, ordinò che gli fosse condotto davanti il ragazzo e promise che, a meno che questo miracolo non si fosse compiuto, avrebbe fatto trascinare a morte il principe legato alla coda di un cavallo.

A dispetto di ciò che I soldati avevano detto, il ragazzo non sapeva più del re in quanto a magia, e il suo compito sembrava senza speranza più di prima. Stava piangendo nella stanza che gli era stato proibito di lasciare quando improvvisamente sentì un rapido bussare alla finestra e, guardando su, vide una cicogna.

”Che cosa ti rende così triste, principe?” chiese l’animale.

”Qualcuno ha detto al re che io ho profetizzato che stanotte a palazzo sarebbe nato un bambino capace di parlare tutte le lingue del mondo e di suonare qualsiasi strumento musicale. Io non sono un mago che possa far sì queste cose avvengano, ma il re ha detto che non accadrà, mi farà trascinare per la città finché muoio legato a coda di un cavallo.”

”Non angustiarti.” rispose la cicogna. Farò in modo di trovare un bambino così perché io sono il re delle cicogne al quale hai risparmiato la vita e adesso posso ripagarti per questo.”

La cicogna volò via e tornò presto reggendo con il becco un bambino avvolto in fasce e con accanto un liuto. In un attimo il bambino stese le manine e cominciò a suonare una melodia così meravigliosa che persino il principe nel sentirla dimenticò le proprie pene. Poi gli furono dati un flauto e una cetra, e lui fu in grado comunque di ricavarne musica; il principe, che stava riprendendo coraggio pian piano, gli parlò in tutte le lingue che conosceva. Il bambino gli rispose in tutte e nessuno avrebbe saputo dire quale fosse la sua lingua natale!

Il mattino seguente il re andò direttamente nella stanza del principe e vide con i propri occhi le meraviglie che il bambino sapeva compiere. “Se la tua magia ha potuto creare un bambino simile,” disse, “tu devi essere più grande di qualsiasi mago mai vissuto e ti darò in sposa mia figlia.” Essendo un re, abituato ad avere tutto appena lo voleva, comandò che la cerimonia fosse celebrata senza indugio e fosse allestita una splendida festa per la sposa e per lo sposo. Quando fu finita, disse al principe:

”Ora che sei davvero mio figlio, dimmi con quali arti sei riuscito a svolgere i compiti che ti avevo affidato?”

Il principe rispose: “Mio nobile suocero, sono digiuno di tutti gli incantesimi e le arti. Ma in un modo o nell’altro sono sempre riuscito a scampare alla morte che mi era stata minacciata. “ e raccontò al re come fosse stato costretto a fuggire dal patrigno e come avesse risparmiato la vita a tre uccelli, e come si fosse unito ai due soldati i quali per invidia avevano fatto il possibile per rovinarlo.

In cuor proprio il re gioì che la figlia avesse sposato un principe e non un uomo qualsiasi, e cacciò i soldati a colpi di frusta, dicendo loro che se avessero mai osato mostrare le loro facce ai confini del regno, sarebbero morti della medesima morte che lui aveva decretato per il principe.

Dalla tradizione popolare ungherese

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)