The Witch and her Servants

(MP3-40'08'')

A long time ago there lived a King who had three sons; the eldest was called Szabo, the second Warza, and the youngest Iwanich.

One beautiful spring morning the King was walking through his gardens with these three sons, gazing with admiration at the various fruit-trees, some of which were a mass of blossom, whilst others were bowed to the ground laden with rich fruit. During their wanderings they came unperceived on a piece of waste land where three splendid trees grew. The King looked on them for a moment, and then, shaking his head sadly, he passed on in silence.

The sons, who could not understand why he did this, asked him the reason of his dejection, and the King told them as follows:

'These three trees, which I cannot see without sorrow, were planted by me on this spot when I was a youth of twenty. A celebrated magician, who had given the seed to my father, promised him that they would grow into the three finest trees the world had ever seen. My father did not live to see his words come true; but on his death-bed he bade me transplant them here, and to look after them with the greatest care, which I accordingly did. At last, after the lapse of five long years, I noticed some blossoms on the branches, and a few days later the most exquisite fruit my eyes had ever seen.

'I gave my head-gardener the strictest orders to watch the trees carefully, for the magician had warned my father that if one unripe fruit were plucked from the tree, all the rest would become rotten at once. When it was quite ripe the fruit would become a golden yellow.

'Every day I gazed on the lovely fruit, which became gradually more and more tempting-looking, and it was all I could do not to break the magician's commands.

'One night I dreamt that the fruit was perfectly ripe; I ate some of it, and it was more delicious than anything I had ever tasted in real life. As soon as I awoke I sent for the gardener and asked him if the fruit on the three trees had not ripened in the night to perfection.

'But instead of replying, the gardener threw himself at my feet and swore that he was innocent. He said that he had watched by the trees all night, but in spite of it, and as if by magic, the beautiful trees had been robbed of all their fruit.

'Grieved as I was over the theft, I did not punish the gardener, of whose fidelity I was well assured, but I determined to pluck off all the fruit in the following year before it was ripe, as I had not much belief in the magician's warning.

'I carried out my intention, and had all the fruit picked off the tree, but when I tasted one of the apples it was bitter and unpleasant, and the next morning the rest of the fruit had all rotted away.

'After this I had the beautiful fruit of these trees carefully guarded by my most faithful servants; but every year, on this very night, the fruit was plucked and stolen by an invisible hand, and next morning not a single apple remained on the trees. For some time past I have given up even having the trees watched.'

When the King had finished his story, Szabo, his eldest son, said to him: 'Forgive me, father, if I say I think you are mistaken. I am sure there are many men in your kingdom who could protect these trees from the cunning arts of a thieving magician; I myself, who as your eldest son claim the first right to do so, will mount guard over the fruit this very night.'

The King consented, and as soon as evening drew on Szabo climbed up on to one of the trees, determined to protect the fruit even if it cost him his life. So he kept watch half the night; but a little after midnight he was overcome by an irresistible drowsiness, and fell fast asleep. He did not awake till it was bright daylight, and all the fruit on the trees had vanished.

The following year Warza, the second brother, tried his luck, but with the same result. Then it came to the turn of the third and youngest son.

Iwanich was not the least discouraged by the failure of his elder brothers, though they were both much older and stronger than he was, and when night came climbed up the tree as they had done. The moon had risen, and with her soft light lit up the whole neighbourhood, so that the observant Prince could distinguish the smallest object distinctly.

At midnight a gentle west wind shook the tree, and at the same moment a snow-white swan-like bird sank down gently on his breast. The Prince hastily seized the bird's wings in his hands, when, lo! to his astonishment he found he was holding in his arms not a bird but the most beautiful girl he had ever seen.

'You need not fear Militza,' said the beautiful girl, looking at the Prince with friendly eyes. 'An evil magician has not robbed you of your fruit, but he stole the seed from my mother, and thereby caused her death. When she was dying she bade me take the fruit, which you have no right to possess, from the trees every year as soon as it was ripe. This I would have done to-night too, if you had not seized me with such force, and so broken the spell I was under.'

Iwanich, who had been prepared to meet a terrible magician and not a lovely girl, fell desperately in love with her. They spent the rest of the night in pleasant conversation, and when Militza wished to go away he begged her not to leave him.

'I would gladly stay with you longer,' said Militza, 'but a wicked witch once cut off a lock of my hair when I was asleep, which has put me in her power, and if morning were still to find me here she would do me some harm, and you, too, perhaps.'

Having said these words, she drew a sparkling diamond ring from her finger, which she handed to the Prince, saying: 'Keep this ring in memory of Militza, and think of her sometimes if you never see her again. But if your love is really true, come and find me in my own kingdom. I may not show you the way there, but this ring will guide you.

'If you have love and courage enough to undertake this journey, whenever you come to a cross-road always look at this diamond before you settle which way you are going to take. If it sparkles as brightly as ever go straight on, but if its lustre is dimmed choose another path.'

Then Militza bent over the Prince and kissed him on his forehead, and before he had time to say a word she vanished through the branches of the tree in a little white cloud.

Morning broke, and the Prince, still full of the wonderful apparition, left his perch and returned to the palace like one in a dream, without even knowing if the fruit had been taken or not; for his whole mind was absorbed by thoughts of Militza and how he was to find her.

As soon as the head-gardener saw the Prince going towards the palace he ran to the trees, and when he saw them laden with ripe fruit he hastened to tell the King the joyful news. The King was beside himself for joy, and hurried at once to the garden and made the gardener pick him some of the fruit. He tasted it, and found the apple quite as luscious as it had been in his dream. He went at once to his son Iwanich, and after embracing him tenderly and heaping praises on him, he asked him how he had succeeded in protecting the costly fruit from the power of the magician.

This question placed Iwanich in a dilemma. But as he did not want the real story to be known, he said that about midnight a huge wasp had flown through the branches, and buzzed incessantly round him. He had warded it off with his sword, and at dawn, when he was becoming quite worn out, the wasp had vanished as suddenly as it had appeared.

The King, who never doubted the truth of this tale, bade his son go to rest at once and recover from the fatigues of the night; but he himself went and ordered many feasts to be held in honour of the preservation of the wonderful fruit.

The whole capital was in a stir, and everyone shared in the King's joy; the Prince alone took no part in the festivities.

While the King was at a banquet, Iwanich took some purses of gold, and mounting the quickest horse in the royal stable, he sped off like the ]wind without a single soul being any the wiser.

It was only on the next day that they missed him; the King was very distressed at his disappearance, and sent search-parties all over the kingdom to look for him, but in vain; and after six months they gave him up as dead, and in another six months they had forgotten all about him. But in the meantime the Prince, with the help of his ring, had had a most successful journey, and no evil had befallen him.

At the end of three months he came to the entrance of a huge forest, which looked as if it had never been trodden by human foot before, and which seemed to stretch out indefinitely. The Prince was about to enter the wood by a little path he had discovered, when he heard a voice shouting to him: 'Hold, youth! Whither are you going?'

Iwanich turned round, and saw a tall, gaunt-looking man, clad in miserable rags, leaning on a crooked staff and seated at the foot of an oak tree, which was so much the same colour as himself that it was little wonder the Prince had ridden past the tree without noticing him.

'Where else should I be going,' he said, 'than through the wood?'

'Through the wood?' said the old man in amazement. 'It's easily seen that you have heard nothing of this forest, that you rush so blindly to meet your doom. Well, listen to me before you ride any further; let me tell you that this wood hides in its depths a countless number of the fiercest tigers, hyenas, wolves, bears, and snakes, and all sorts of other monsters. If I were to cut you and your horse up into tiny morsels and throw them to the beasts, there wouldn't be one bit for each hundred of them. Take my advice, therefore, and if you wish to save your life follow some other path.'

The Prince was rather taken aback by the old man's words, and considered for a minute what he should do; then looking at his ring, and perceiving that it sparkled as brightly as ever, he called out: 'If this wood held even more terrible things than it does, I cannot help myself, for I must go through it.'

Here he spurred his horse and rode on; but the old beggar screamed so loudly after him that the Prince turned round and rode back to the oak tree.

'I am really sorry for you,' said the beggar, 'but if you are quite determined to brave the dangers of the forest, let me at least give you a piece of advice which will help you against these monsters.'

'Take this bagful of bread-crumbs and this live hare. I will make you a present of them both, as I am anxious to save your life; but you must leave your horse behind you, for it would stumble over the fallen trees or get entangled in the briers and thorns. When you have gone about a hundred yards into the wood the wild beasts will surround you. Then you must instantly seize your bag, and scatter the bread-crumbs among them. They will rush to eat them up greedily, and when you have scattered the last crumb you must lose no time in throwing the hare to them; as soon as the hare feels itself on the ground it will run away as quickly as possible, and the wild beasts will turn to pursue it. In this way you will be able to get through the wood unhurt.'

Iwanich thanked the old man for his counsel, dismounted from his horse, and, taking the bag and the hare in his arms, he entered the forest. He had hardly lost sight of his gaunt grey friend when he heard growls and snarls in the thicket close to him, and before he had time to think he found himself surrounded by the most dreadful-looking creatures. On one side he saw the glittering eye of a cruel tiger, on the other the gleaming teeth of a great she-wolf; here a huge bear growled fiercely, and there a horrible snake coiled itself in the grass at his feet.

But Iwanich did not forget the old man's advice, and quickly put his hand into the bag and took out as many bread-crumbs as he could hold in his hand at a time. He threw them to the beasts, but soon the bag grew lighter and lighter, and the Prince began to feel a little frightened. And now the last crumb was gone, and the hungry beasts thronged round him, greedy for fresh prey. Then he seized the hare and threw it to them.

No sooner did the little creature feel itself on the ground than it lay back its ears and flew through the wood like an arrow from a bow, closely pursued by the wild beasts, and the Prince was left alone. He looked at his ring, and when he saw that it sparkled as brightly as ever he went straight on through the forest.

He hadn't gone very far when he saw a most extraordinary looking man coming towards him. He was not more than three feet high, his legs were quite crooked, and all his body was covered with prickles like a hedgehog. Two lions walked with him, fastened to his side by the two ends of his long beard.

He stopped the Prince and asked him in a harsh voice: 'Are you the man who has just fed my body-guard?'

Iwanich was so startled that he could hardly reply, but the little man continued: 'I am most grateful to you for your kindness; what can I give you as a reward?'

'All I ask,' replied Iwanich, 'is, that I should be allowed to go through this wood in safety.'

'Most certainly,' answered the little man; 'and for greater security I will give you one of my lions as a protector. But when you leave this wood and come near a palace which does not belong to my domain, let the lion go, in order that he may not fall into the hands of an enemy and be killed.'

With these words he loosened the lion from his beard and bade the beast guard the youth carefully.

With this new protector Iwanich wandered on through the forest, and though he came upon a great many more wolves, hyenas, leopards, and other wild beasts, they always kept at a respectful distance when they saw what sort of an escort the Prince had with him.

Iwanich hurried through the wood as quickly as his legs would carry him, but, nevertheless, hour after hour, went by and not a trace of a green field or a human habitation met his eyes. At length, towards evening, the mass of trees grew more transparent, and through the interlaced branches a wide plain was visible.

At the exit of the wood the lion stood still, and the Prince took leave of him, having first thanked him warmly for his kind protection. It had become quite dark, and Iwanich was forced to wait for daylight before continuing his journey.

He made himself a bed of grass and leaves, lit a fire of dry branches, and slept soundly till the next morning.

Then he got up and walked towards a beautiful white palace which he saw gleaming in the distance. In about an hour he reached the building, and opening the door he walked in.

After wandering through many marble halls, he came to a huge staircase made of porphyry, leading down to a lovely garden.

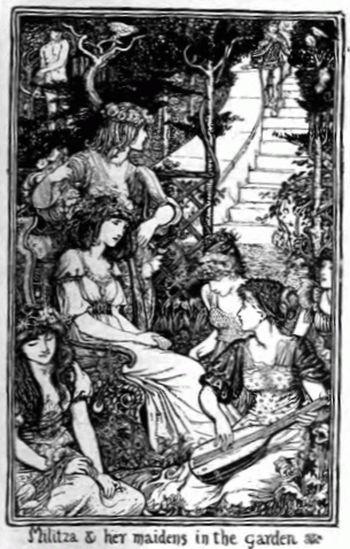

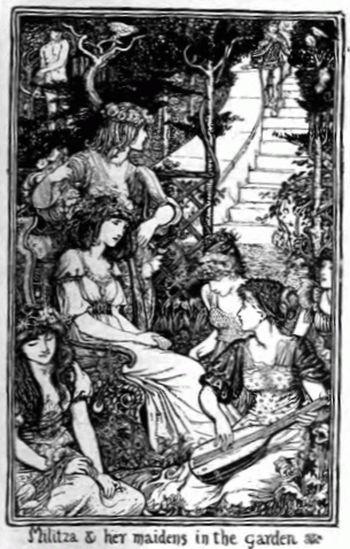

The Prince burst into a shout of joy when he suddenly perceived Militza in the centre of a group of girls who were weaving wreaths of flowers with which to deck their mistress.

As soon as Militza saw the Prince she ran up to him and embraced him tenderly; and after he had told her all his adventures, they went into the palace, where a sumptuous meal awaited them. Then the Princess called her court together, and introduced Iwanich to them as her future husband.

Preparations were at once made for the wedding, which was held soon after with great pomp and magnificence.

Three months of great happiness followed, when Militza received one day an invitation to visit her mother's sister.

Although the Princess was very unhappy at leaving her husband, she did not like to refuse the invitation, and, promising to return in seven days at the latest, she took a tender farewell of the Prince, and said: 'Before I go I will hand you over all the keys of the castle. Go everywhere and do anything you like; only one thing I beg and beseech you, do not open the little iron door in the north tower, which is closed with seven locks and seven bolts; for if you do, we shall both suffer for it.'

Iwanich promised what she asked, and Militza departed, repeating her promise to return in seven days.

When the Prince found himself alone he began to be tormented by pangs of curiosity as to what the room in the tower contained. For two days he resisted the temptation to go and look, but on the third he could stand it no longer, and taking a torch in his hand he hurried to the tower, and unfastened one lock after the other of the little iron door until it burst open.

What an unexpected sight met his gaze! The Prince perceived a small room black with smoke, lit up feebly by a fire from which issued long blue flames. Over the fire hung a huge cauldron full of boiling pitch, and fastened into the cauldron by iron chains stood a wretched man screaming with agony.

Iwanich was much horrified at the sight before him, and asked the man what terrible crime he had committed to be punished in this dreadful fashion.

'I will tell you everything,' said the man in the cauldron; 'but first relieve my torments a little, I implore you.'

'And how can I do that?' asked the Prince.

'With a little water,' replied the man; 'only sprinkle a few drops over me and I shall feel better.'

The Prince, moved by pity, without thinking what he was doing, ran to the courtyard of the castle, and filled a jug with water, which he poured over the man in the cauldron.

In a moment a most fearful crash was heard, as if all the pillars of the palace were giving way, and the palace itself, with towers and doors, windows and the cauldron, whirled round the bewildered Prince's head. This continued for a few minutes, and then everything vanished into thin air, and Iwanich found himself suddenly alone upon a desolate heath covered with rocks and stones.

The Prince, who now realised what his heedlessness had done, cursed too late his spirit of curiosity. In his despair he wandered on over the heath, never looking where he put his feet, and full of sorrowful thoughts. At last he saw a light in the distance, which came from a miserable-looking little hut.

The owner of it was none other than the kind-hearted gaunt grey beggar who had given the Prince the bag of bread-crumbs and the hare. Without recognising Iwanich, he opened the door when he knocked and gave him shelter for the night.

On the following morning the Prince asked his host if he could get him any work to do, as he was quite unknown in the neighbourhood, and had not enough money to take him home.

'My son,' replied the old man, 'all this country round here is uninhabited; I myself have to wander to distant villages for my living, and even then I do not very often find enough to satisfy my hunger. But if you would like to take service with the old witch Corva, go straight up the little stream which flows below my hut for about three hours, and you will come to a sand-hill on the left-hand side; that is where she lives.'

Iwanich thanked the gaunt grey beggar for his information, and went on his way.

After walking for about three hours the Prince came upon a dreary-looking grey stone wall; this was the back of the building and did not attract him; but when he came upon the front of the house he found it even less inviting, for the old witch had surrounded her dwelling with a fence of spikes, on every one of which a man's skull was stuck. In this horrible enclosure stood a small black house, which had only two grated windows, all covered with cobwebs, and a battered iron door.

The Prince knocked, and a rasping woman's voice told him to enter.

Iwanich opened the door, and found himself in a smoke-begrimed kitchen, in the presence of a hideous old woman who was warming her skinny hands at a fire. The Prince offered to become her servant, and the old hag told him she was badly in want of one, and he seemed to be just the person to suit her.

When Iwanich asked what his work, and how much his wages would be, the witch bade him follow her, and led the way through a narrow damp passage into a vault, which served as a stable. Here he perceived two pitch-black horses in a stall.

'You see before you,' said the old woman, 'a mare and her foal; you have nothing to do but to lead them out to the fields every day, and to see that neither of them runs away from you. If you look after them both for a whole year I will give you anything you like to ask; but if, on the other hand, you let either of the animals escape you, your last hour is come, and your head shall be stuck on the last spike of my fence. The other spikes, as you see, are already adorned, and the skulls are all those of different servants I have had who have failed to do what I demanded.'

Iwanich, who thought he could not be much worse off than he was already, agreed to the witch's proposal.

At daybreak next morning he drove his horses to the field, and brought them back in the evening without their ever having attempted to break away from him. The witch stood at her door and received him kindly, and set a good meal before him.

So it continued for some time, and all went well with the Prince. Early every morning he led the horses out to the fields, and brought them home safe and sound in the evening.

One day, while he was watching the horses, he came to the banks of a river, and saw a big fish, which through some mischance had been cast on the land, struggling hard to get back into the water.

Iwanich, who felt sorry for the poor creature, seized it in his arms and flung it into the stream. But no sooner did the fish find itself in the water again, than, to the Prince's amazement, it swam up to the bank and said:

'My kind benefactor, how can I reward you for your goodness?'

'I desire nothing,' answered the Prince. 'I am quite content to have been able to be of some service to you.'

'You must do me the favour,' replied the fish, 'to take a scale from my body, and keep it carefully. If you should ever need my help, throw it into the river, and I will come to your aid at once.'

Iwanich bowed, loosened a scale from the body of the grateful beast, put it carefully away, and returned home.

A short time after this, when he was going early one morning to the usual grazing place with his horses, he noticed a flock of birds assembled together making a great noise and flying wildly backwards and forwards.

Full of curiosity, Iwanich hurried up to the spot, and saw that a large number of ravens had attacked an eagle, and although the eagle was big and powerful and was making a brave fight, it was overpowered at last by numbers, and had to give in.

But the Prince, who was sorry for the poor bird, seized the branch of a tree and hit out at the ravens with it; terrified at this unexpected onslaught they flew away, leaving many of their number dead or wounded on the battlefield.

As soon as the eagle saw itself free from its tormentors it plucked a feather from its wing, and, handing it to the Prince, said: 'Here, my kind benefactor, take this feather as a proof of my gratitude; should you ever be in need of my help blow this feather into the air, and I will help you as much as is in my power.'

Iwanich thanked the bird, and placing the feather beside the scale he drove the horses home.

Another day he had wandered farther than usual, and came close to a farmyard; the place pleased the Prince, and as there was plenty of good grass for the horses he determined to spend the day there. Just as he was sitting down under a tree he heard a cry close to him, and saw a fox which had been caught in a trap placed there by the farmer.

In vain did the poor beast try to free itself; then the good-natured Prince came once more to the rescue, and let the fox out of the trap.

The fox thanked him heartily, tore two hairs out of his bushy tail, and said: 'Should you ever stand in need of my help throw these two hairs into the fire, and in a moment I shall be at your side ready to obey you.'

Iwanich put the fox's hairs with the scale and the feather, and as it was getting dark he hastened home with his horses.

In the meantime his service was drawing near to an end, and in three more days the year was up, and he would be able to get his reward and leave the witch.

On the first evening of these last three days, when he came home and was eating his supper, he noticed the old woman stealing into the stables.

The Prince followed her secretly to see what she was going to do. He crouched down in the doorway and heard the wicked witch telling the horses to wait next morning till Iwanich was asleep, and then to go and hide themselves in the river, and to stay there till she told them to return; and if they didn't do as she told them the old woman threatened to beat them till they bled.

When Iwanich heard all this he went back to his room, determined that nothing should induce him to fall asleep next day. On the following morning he led the mare and foal to the fields as usual, but bound a cord round them both which he kept in his hand.

But after a few hours, by the magic arts of the old witch, he was overpowered by sleep, and the mare and foal escaped and did as they had been told to do. The Prince did not awake till late in the evening; and when he did, he found, to his horror, that the horses had disappeared. Filled with despair, he cursed the moment when he had entered the service of the cruel witch, and already he saw his head sticking up on the sharp spike beside the others.

Then he suddenly remembered the fish's scale, which, with the eagle's feather and the fox's hairs, he always carried about with him. He drew the scale from his pocket, and hurrying to the river he threw it in. In a minute the grateful fish swam towards the bank on which Iwanich was standing, and said: 'What do you command, my friend and benefactor?'

The Prince replied: 'I had to look after a mare and foal, and they have run away from me and have hidden themselves in the river; if you wish to save my life drive them back to the land.'

'Wait a moment,' answered the fish, 'and I and my friends will soon ]drive them out of the water.' With these words the creature disappeared into the depths of the stream.

Almost immediately a rushing hissing sound was heard in the waters, the waves dashed against the banks, the foam was tossed into the air, and the two horses leapt suddenly on to the dry land, trembling and shaking with fear.

Iwanich sprang at once on to the mare's back, seized the foal by its bridle, and hastened home in the highest spirits.

When the witch saw the Prince bringing the horses home she could hardly conceal her wrath, and as soon as she had placed Iwanich's supper before him she stole away again to the stables. The Prince followed her, and heard her scolding the beasts harshly for not having hidden themselves better. She bade them wait next morning till Iwanich was asleep and then to hide themselves in the clouds, and to remain there till she called. If they did not do as she told them she would beat them till they bled.

The next morning, after Iwanich had led his horses to the fields, he fell once more into a magic sleep. The horses at once ran away and hid themselves in the clouds, which hung down from the mountains in soft billowy masses.

When the Prince awoke and found that both the mare and the foal had disappeared, he bethought him at once of the eagle, and taking the feather out of his pocket he blew it into the air.

In a moment the bird swooped down beside him and asked: 'What do you wish me to do?'

'My mare and foal,' replied the Prince, 'have run away from me, and have hidden themselves in the clouds; if you wish to save my life, restore both animals to me.'

'Wait a minute,' answered the eagle; 'with the help of my friends I will soon drive them back to you.'

With these words the bird flew up into the air and disappeared among the clouds.

Almost directly Iwanich saw his two horses being driven towards him by a host of eagles of all sizes. He caught the mare and foal, and having thanked the eagle he drove them cheerfully home again.

The old witch was more disgusted than ever when she saw him appearing, and having set his supper before him she stole into the stables, and Iwanich heard her abusing the horses for not having hidden themselves better in the clouds. Then she bade them hide themselves next morning, as soon as Iwanich was asleep, in the King's hen-house, which stood on a lonely part of the heath, and to remain there till she called. If they failed to do as she told them she would certainly beat them this time till they bled.

On the following morning the Prince drove his horses as usual to the fields. After he had been overpowered by sleep, as on the former days, the mare and foal ran away and hid themselves in the royal hen-house.

When the Prince awoke and found the horses gone he determined to appeal to the fox; so, lighting a fire, he threw the two hairs into it, and in a few moments the fox stood beside him and asked: 'In what way can I serve you?'

'I wish to know,' replied Iwanich, 'where the King's hen-house is.'

'Hardly an hour's walk from here,' answered the fox, and offered to show the Prince the way to it.

While they were walking along the fox asked him what he wanted to do at the royal hen-house. The Prince told him of the misfortune that had befallen him, and of the necessity of recovering the mare and foal.

'That is no easy matter,' replied the fox. 'But wait a moment. I have an idea. Stand at the door of the hen-house, and wait there for your horses. In the meantime I will slip in among the hens through a hole in the wall and give them a good chase, so that the noise they make will arouse the royal henwives, and they will come to see what is the matter. When they see the horses they will at once imagine them to be the cause of the disturbance, and will drive them out. Then you must lay hands on the mare and foal and catch them.’

All turned out exactly as the sly fox had foreseen. The Prince swung himself on the mare, seized the foal by its bridle, and hurried home.

While he was riding over the heath in the highest of spirits the mare suddenly said to her rider: 'You are the first person who has ever succeeded in outwitting the old witch Corva, and now you may ask what reward you like for your service. If you promise never to betray me I will give you a piece of advice which you will do well to follow.'

The Prince promised never to betray her confidence, and the mare continued: 'Ask nothing else as a reward than my foal, for it has not its like in the world, and is not to be bought for love or money; for it can go from one end of the earth to another in a few minutes. Of course the cunning Corva will do her best to dissuade you from taking the foal, and will tell you that it is both idle and sickly; but do not believe her, and stick to your point.'

Iwanich longed to possess such an animal, and promised the mare to follow her advice.

This time Corva received him in the most friendly manner, and set a sumptuous repast before him. As soon as he had finished she asked him what reward he demanded for his year's service.

'Nothing more nor less,' replied the Prince, 'than the foal of your mare.'

The witch pretended to be much astonished at his request, and said that he deserved something much better than the foal, for the beast was lazy and nervous, blind in one eye, and, in short, was quite worthless.

But the Prince knew what he wanted, and when the old witch saw that he had made up his mind to have the foal, she said, 'I am obliged to keep my promise and to hand you over the foal; and as I know who you are and what you want, I will tell you in what way the animal will be useful to you. The man in the cauldron of boiling pitch, whom you set free, is a mighty magician; through your curiosity and thoughtlessness Militza came into his power, and he has transported her and her castle and belongings into a distant country.

'You are the only person who can kill him; and in consequence he fears you to such an extent that he has set spies to watch you, and they report your movements to him daily.

'When you have reached him, beware of speaking a single word to him, or you will fall into the power of his friends. Seize him at once by the beard and dash him to the ground.'

Iwanich thanked the old witch, mounted his foal, put spurs to its sides, and they flew like lightning through the air.

Already it was growing dark, when Iwanich perceived some figures in the distance; they soon came up to them, and then the Prince saw that it was the magician and his friends who were driving through the air in a carriage drawn by owls.

When the magician found himself face to face with Iwanich, without hope of escape, he turned to him with false friendliness and said: 'Thrice my kind benefactor!'

But the Prince, without saying a word, seized him at once by his beard and dashed him to the ground. At the same moment the foal sprang on the top of the magician and kicked and stamped on him with his hoofs till he died.

Then Iwanich found himself once more in the palace of his bride, and Militza herself flew into his arms.

From this time forward they lived in undisturbed peace and happiness till the end of their lives. .

From the Russian. Kletke.

La strega e i suoi servi

Tanto tempo fa viveva un re che aveva tre figli; il maggiore si chiamava Szabo, il secondo Warza e il minore Iwanich.

In uno splendido mattino di primavera il re stava passeggiando nei suoi giardini con i tre figli, osservando con ammirazione la varietà degli alberi da frutto, alcuni dei quali erano in piena fioritura mentre altri si curvavano fino a terra carichi di abbondanti frutti. Durante il loro girovagare giunsero inavvertitamente in un tratto di terra incolta sulla quale crescevano tre splendidi alberi. Il re li guardò per un momento e poi, scrollando tristemente il capo, passò oltre in silenzio.

I figli, che non comprendevano perché lo avesse fatto, gli chiesero ragione di quello scoramento e il re narrò loro ciò che segue:

“Quei tre alberi, che non posso vedere senza rattristarmi, furono piantati da me in quel punto quando ero un giovane di vent’anni. Un rinomato mago, che aveva dato i semi a mio padre, gli aveva promesso che sarebbero diventati i più begli alberi che il mondo avesse mai visto. Mio padre non visse abbastanza per vedere quelle parole trasformarsi in verità, ma sul letto di morte mi ordinò di trapiantarli qui e di seguirli con la più grande cura, cosa che io di conseguenza feci. Alla fine, dopo cinque lunghi anni, mi accorsi di alcuni fiori sui rami e pochi giorni più tardi del frutto più squisito che i miei occhi avessero mai visto.

“Diedi al mio capo giardiniere i più severi di sorvegliare attentamente gli alberi perché il mago aveva avvertito mio padre che se un frutto acerbo fosse stato colto dall’albero, tutti gli altri sarebbero marciti subito. Quando fosse stato completamente maturo, il frutto sarebbe diventato giallo oro.

“Ogni giorno osservavo il bel frutto, che diventava pian piano sempre più allettante, e feci il possibile per non trasgredire gli ordini del mago.

“Una notte sognai che il frutto era perfettamente maturo, che ne mangiavo un po’ ed

era più delizioso di qualsiasi cosa io avessi assaggiato nella vita reale. Appena mi svegliai, mandai a chiamare il giardiniere e gli chiesi se il frutto sui tre alberi non fosse maturato alla perfezione durante la notte.

“Invece di rispondere, il giardiniere si gettò ai miei piedi e giurò di essere innocente. Disse di aver sorvegliato per tutta la notte i tre alberi eppure, malgrado ciò e come per magia, i meravigliosi alberi erano stati depredati tutti del loro frutto.

“Addolorato come ero per il furto, non punii il giardiniere, della cui fedeltà ero ben certo, ma decisi di cogliere tutti i frutti l’anno seguente prima che fossero maturi, non avendo molta fiducia nell’ammonimento del mago.

“Misi in atto il mio intento e il frutto fu colto da ogni albero, ma quando assaggiai una delle mele era amara e sgradevole e il mattino seguente gli altri frutti erano tutti marciti.

“Dopo di ciò il bellissimo frutto dei tre alberi fu sorvegliato attentamente dai miei servitori più fedeli, ma ogni anno, proprio in quella notte, il frutto veniva colto e rubato da una mano invisibile e il mattino seguente non era rimasta sugli alberi una sola mela. Diverso tempo dopo mi arresi sebbene avessi fatto sorvegliare gli alberi.”

Quando il re ebbe finito la storia, Szabo, il figlio maggiore, gli disse: “Perdonami, padre, se dico che penso tu abbia sbagliato. Sono certo ci sarebbero stai molti uomini nel tuo regno che avrebbero potuto proteggere quegli alberi dalle astute arti di un mago dedito al furto; io stesso, che in qualità di tuo figlio maggiore reclamo per primo il diritto di farlo, monterò la guardia presso il frutto proprio questa notte.”

Il re acconsentì e, appena si fece sera, Szabo si arrampicò su uno degli alberi, deciso a proteggere il frutto anche a costo della vita. Così fece la guardia fino a mezzanotte, ma poco dopo fu sopraffatto da un’irresistibile sonnolenza e ben preso si addormentò. Non si svegliò finché non fu pieno giorno e ogni frutto sugli alberi era svanito.

L’anno seguente Warza, il secondogenito, tentò la sorte, ma con il medesimo risultato. Allora venne il turno del terzo figlio, il minore.

Iwanich non fu minimamente scoraggiato dal fallimento dei fratelli maggiori, sebbene fossero entrambi più grandi e più forti di lui, e, quando scese la notte, si arrampicò sull’albero come avevano fatto loro. Sorse la luna e con la sua luce delicata illuminata tutti i dintorni, così che l’attento principe poteva scorgere distintamente i più piccoli oggetti.

A mezzanotte un leggero vento da ovest scosse l’albero e nel medesimo istante un cigno bianco si posò delicatamente come un uccello sul suo petto. Il principe gli afferrò rapidamente le ali con le mani quand’ecco, con suo grande stupore, scoprì di tenere fra le braccia non un uccello ma la più bella ragazza che avesse mai visto.

“Non devi temere Militza.” disse la splendida ragazza, guardando il principe con occhi amichevoli. “Un mago malvagio non vi ha derubato del frutto, ma ha sottratto il seme a mia madre e perciò ha causato la sua morte. Mentre stava morendo, mi ha ordinato di prendere il frutto, che voi non avete il diritto di possedere, ogni anno dagli alberi appena è maturo. E ciò avrei fatto anche stanotte, se tu non mi avessi afferrata con tale forza e non avessi così spezzato l’incantesimo sotto il quale mi trovavo.”

Iwanich, che si era preparato ad affrontare un terribile mago e non una leggiadra ragazza, si innamorò perdutamente di lei. Poi trascorse il resto della notte in piacevole conversazione e, quando Militza volle andar via, la pregò di non lasciarlo.

“Mi piacerebbe stare più a lungo con te,” disse Militza, “ma una malvagia strega una volta mi ha tagliato una ciocca di capelli mentre dormivo e che mi tiene in suo potere, e se il mattino mi sorprendesse qui, lei mi farebbe del male e forse ne farebbe anche a te.”

Pronunciate queste parole, si tolse dal dito un anello con un diamante sfavillante e lo infilò al principe, dicendo: “Conserva questo anello come ricordo di Militza e pensa a lei qualche volta se non la vedrai mai di nuovo. Ma se il tuo amore è sincero, vieni a trovarmi nel mio regno. Non posso mostrarti qui la via, ma l’anello ti guiderà.

“Se avrai abbastanza amore e coraggio da intraprendere questo viaggio, ogni volta in cui ti troverai a un incrocio, guarda sempre questo diamante prima di decidere quale strada dovrai prendere. Se scintillerà più luminoso che mai, imbocca la strada, ma se la sua lucentezza si offuscherà, scegline un’altra.”

Poi Militza si chinò sul principe, lo baciò sulla fronte e, prima che lui avesse il tempo di dire una parola, svanì tra i rami dell’albero in una piccola nube bianca.

Si fece mattina e il principe, dominato dalla meravigliosa apparizione, lasciò il ramo e tornò a palazzo come in sogno, senza neppure sapere se il frutto fosse stato preso o no perché tutta la sua mente era assorbita dal pensiero di Militza e di come trovarla.

Appena il giardiniere capo vide il principe dirigersi verso il palazzo, corse agli alberi e, quando li vide carichi del frutto maturo, si affrettò a dare al re la felice notizia. Il re era fuori di sé per la contentezza e si affrettò subito in giardino poi mandò il giardiniere a cogliergli un frutto, lo assaggiò e scoprì che la mela era succulenta proprio come aveva sognato. Andò subito dal figlio Iwanich e, dopo averlo abbracciato con tenerezza e colmato di elogi, gli chiese come fosse riuscito a proteggere il prezioso frutto dal potere del mago.

La domanda pose Iwanich di fronte a un dilemma, ma siccome non voleva che la vera storia fosse nota, disse che intorno a mezzanotte un’enorme vespa era volta tra i rami ronzando incessantemente intorno lui. L’aveva scansata con la spada e all’alba, quando stava incominciando a sentirsi esausto, la vespa era svanita improvvisamente come era giunta.

Il re, che non dubitò della veridicità della storia, mandò subito il figlio a riposare a riprendersi dalle fatiche della notte; poi egli stesso andò a ordinare che fossero idetti festeggiamenti in onore della conservazione del frutto meraviglioso.

Tutta la capitale era in agitazione e ognuno condivideva la gioia del re;solo il principe non prese parte ai festeggiamenti.

Mentre il re era al banchetto, Iwanich prese alcune borse d’oro e, montando in sella al cavallo più veloce della scuderia reale, partì veloce come il vento senza che anima viva ne fosse informata.

Fu solo il giorno seguente che si accorsero della sua scomparsa; il re fu molto afflitto per la sua sparizione e mandò squadre di ricerca a cercarlo in tutto il regno, ma invano; dopo sei mesi lo diedero per morto e dopo altri sei mesi se l’erano del tutto dimenticato. Ma nel frattempo il principe, con l’aiuto dell’anello, aveva viaggiato con successo e non gli era accaduto nulla di male.

Dopo tre mesi era giunto all’ingresso di un’enorme foresta, che sembrava non essere mai stata attraversata prima da piede umano e stendersi all’infinito. Il principe stava per entrare nella foresta da un piccolo sentiero che aveva scoperto quando udì una voce che gli gridava: “Fermo, ragazzo! Dove stai andando?”

Iwanich si volse attorno e vide un uomo alto e macilento, vestito di miserabili stracci che si appoggiava a un bastone curvo e sedeva ai piedi di una quercia, che ne aveva i medesimi colori tanto che non ci si sarebbe meravigliati se il principe avesse oltrepassato l’albero senza accorgersi di lui.

“Dove vuoi che stia andando se non attraverso il bosco?” disse.

“Attraverso il bosco?” disse il vecchi con stupore. “Si vede chiaramente che tu non abbia sentito nulla di questa foresta in cui ti precipiti alla cieca incontro al tuo destino. Ebbene, ascoltami prima di proseguire; lascia che ti racconti che questo bosco nasconde nelle sue profondità innumerevoli tigri, iene, lupi, orsi e serpenti tra i più feroci e ogni altro genere di mostri. Se facessi a pezzi te e il tuo cavallo e li gettassi alle belve, non ci sarebbe che un boccone per un centinaio di esse. Segui il mio consiglio, dunque, e se vuoi salvarti la vita, segui qualche altro sentiero.”

Il principe fu colto alla sprovvista dalle parole del vecchio e per un minuto valutò il da farsi; poi guardando l’anello e notando che brillava luminoso come non mai, esclamò: “Se questo bosco racchiude sempre cose così terribili non posso essere d’aiuto a me stesso perciò devo attraversarlo.”

Spronò il cavallo e cavalcò via; ma il vecchio gli gridò dietro così forte che il principe si voltò e tornò alla quercia.

“Mi dispiace davvero tanto per te,” disse il mendicante, “ma se sei proprio deciso ad affrontare coraggiosamente i pericoli della foresta, almeno lascia che ti dia un consiglio che ti aiuterà contro quei mostri.

“Prendi questo sacco di briciole di pane e questa lepre viva. Te li donerò entrambi, tanto sono desideroso di salvarti la vita; ma tu devi lasciare indietro il cavallo perché inciamperebbe sugli alberi caduti o si impiglierebbe tra i rovi e e le spine. Quando avrai percorso un centinaio di iarde nel bosco, le bestie feroci ti circonderanno. Allora dovrai subito prendere il sacco e spargere le briciole di pane tra di esse. Si precipiteranno a mangiarle avidamente e, quando avrai sparso le ultime briciole, non dovrai perder tempo nel gettare loro la lepre; appena la lepre toccherà il terreno, correrà via il più in fretta possibile e le bestie feroci si volteranno a inseguirla. In questo modo tu sarai in grado di attraversare incolume il bosco.”

Iwanich ringraziò il vecchio per il consiglio, smontò da cavallo e, prendendo tra le braccia il sacco e la lepre, entrò nella foresta. Aveva appena perso di vista il magro amico vestito di verde quando sentì grugniti e ringhi nel folto intorno a sé e, prima che avesse il tempo di pensare, si trovò circondato dalle più spaventose creature mai viste. Da un lato vide gli occhi luccicanti di una tigre crudele, dall’altro i denti scintillanti di una grande lupa; qui un enorme orso ringhiava ferocemente e là un orribile serpente si avvolgeva a spirale nell’erba ai suoi piedi.

Iwanich però non aveva dimenticato il consiglio del vecchio e in fretta infilò la mano nel sacco e ne tirò fuori tante briciole di pane quante la sua mano poteva contenere in una volta. Le getto alle bestie, ma ben presto il sacco diventò sempre più leggero e il principe cominciò a sentirsi un po’ spaventato. Anche l’ultima briciola era finita e le bestie affamate si affollarono intorno a lui, avide di carne fresca. Allora afferrò la lepre e la gettò verso di esse.

Appena la piccola creatura ebbe toccato terra, abbassò le orecchie e si gettò nel bosco come una freccia, incalzata dalle bestie feroci, e il principe rimase solo. Guardò l’anello e quando vide che brillava lucente come sempre, andò diritto attraverso la foresta.

Non era giunto molto lontano quando vide il più incredibile uomo venire verso di lui. Non era alto più di tre piedi, le sue gambe erano arcuate e aveva tutto il corpo coperto di aculei come un porcospino. Dietro di lui camminavano due leoni, legati ai suoi fianchi dalle due estremità della sua lunga barba.

Egli fermò il principe e gli chiese con voce aspra: “Sei tu l’uomo che ha appena dato da mangiare alla mia guardia del corpo?”

Iwanich era troppo sbigottito per poter appena replicare, ma l’ometto proseguì: “Ti sono molto grato per la tua gentilezza, come posso ricompensarti?”

“Tutto ciò che chiedo” rispose Iwanich, “è che mi sia permesso attraversare il bosco sano e salvo.”

“Certamente” rispose l’ometto, “e per maggior sicurezza, ti darò uno dei miei leoni come protezione. Quando avrai lasciato il bosco e sarai giunto vicino a un palazzo che non appartiene al mio dominio, lascia tornare indietro il leone in modo che non possa cadere in mano a un nemico ed essere ucciso.”

Con queste parole sciolse il leone dalla barba e ordinò alla bestia di seguire attentamente il giovane.

Con questo nuovo protettore Iwanich si aggirò per la foresta e sebbene passasse tra gran quantità di lupi, iene, leopardi e altre bestie selvagge, esse si mantenevano sempre a rispettosa distanza quando vedevano che razza di scorta il principe avesse con sé

Iwanich si sbrigò ad attraversare il bosco il più velocemente gli permisero le gambe ma, tuttavia, ora dopo ora, proseguiva senza che una traccia di un campo verde o di un’abitazione umana comparissero ai suoi occhi. Alla fine, verso sera, gli alberi si fecero più radi e attraverso i rami intrecciati fu visibile una vasta pianura.

All’uscita dal bosco il leone si immobilizzò e il principe si congedo da lui, avendolo prima ringraziato calorosamente per la sua benevola protezione. Si era fatto buio e Iwanich fu obbligato ad attendere la luce del giorno per continuare il viaggio.

Si fece un letto d’erba e di foglie, accese un fuoco con i rami secchi e e dormì saporitamente fino al mattino seguente.

Si alzò e camminò verso un magnifico palazzo che vedeva scintillare a distanza. In circa un’ora lo raggiunse e, aprendo la porta, vi entrò.

Dopo aver attraversato molte sale di marmo, giunse a una grande scalinata di porpora che scendeva in un delizioso giardino.

Il principe esplose in un grido di gioia quando improvvisamente si accorse di Militza al centro di un gruppo di ragazze che stavano intrecciando ghirlande di fiori con le quali adornare la loro signora.

Appena Militza vide il principe, corse verso di lui e lo abbracciò teneramente; dopo che le ebbe narrato tutte le proprie avventure, entrarono nel palazzo in cui li attendeva un sontuoso pasto. Poi la principessa radunò la corte e presentò Iwanich come il proprio futuro marito.

Furono fatti subito i preparativi per le nozze che ebbero luogo poco dopo con grande pompa e magnificenza.

Seguirono tre mesi di grande felicità quando un giorno Militza ricevette l’invito a far visita alla sorella di sua madre.

Sebbene la principessa fosse assai infelice di lasciare il marito, non volle rifiutare l’invito e, promettendo di tornare al più tardi dopo sette giorni, ebbe un tenero commiato dal principe e disse: “Prima che io vada, ti consegnerò tutte le chiavi del castello. Vai dappertutto e fai ciò che ti pare, ma ti supplico e ti imploro solo di una cosa: non aprire la porticina di ferro della torre settentrionale, che è chiusa con sette serrature e sette chiavistelli. Se lo farai, ne soffriremo entrambi.”

Iwanich promise ciò che gli chiedeva e Militza se ne andò, ripetendogli la promessa di tornare in sette giorni.

Quando il principe si ritrovò da solo cominciò a essere tormentato dallo stimolo della curiosità riguardo ciò che contenesse la stanza nella torre. Per due giorni resistette alla tentazione di andare a vedere, ma il terzo giorno non ce la fece più e, prendendo una torcia, andò in fretta alla torre e aprì una dopo l’altra le serrature della porticina di ferro finché si aprì.

Che vista inattesa si offrì al suo sguardo! Il principe vide una stanzetta oscurata dal fumo, che si levava flebile da un fuoco che spandeva fiamme blu. Sul fuoco pendeva un grosso calderone pieno di pece e nel calderone, legato con catene di ferro, c’era uno sventurato uomo che urlava di dolore.

Iwanich fu assai inorridito a quella vista e chiese all’uomo quale terribile crimine avesse commesso per essere punito in questo modo spaventoso.

“Ti dirò tutto,” disse l’uomo nel calderone, “ma prima allevia un po’ i miei tormenti, te ne prego.”

“E come posso farlo?” chiese il principe.

“Con un po’ d’acqua” rispose l’uomo “spruzza su di me poche gocce e io starò meglio.”

Il principe, mosso a compassione, senza pensare a ciò che stava facendo, corse nel cortile del castello, riempì d’acqua una caraffa e la versò sull’uomo nel calderone.

In un attimo si sentì uno schianto spaventoso, come se tutte le colonne del palazzo stessero crollando, e il palazzo stesso, con le sue torri e porte e finestre e il calderone, ruotò intorno alla testa del principe sconcertato. Ciò durò per alcuni minuti e poi tutto svanì nell’aria e Iwanich si trovò improvvisamente solo in una landa desolata ricoperta di rocce e di pietre.

Il principe, che adesso si rendeva conto di quale sciocchezza avesse combinato, maledì troppo tardi la propria curiosità. Disperato vagò per la landa, senza guardare dove mettesse i piedi, colmo di tristi pensieri. Alla fine vide una luce in lontananza, che proveniva da una casupola dall’aspetto miserabile.

Il proprietario altri non era che il gentile mendicante magro che aveva dato al principe la sacca con le briciole e la lepre. Senza riconoscere Iwanich, aprì la porta quando sentì bussare e gli offri ricovero per la notte.

Il mattino seguente il principe chiese all’ospite se avesse qualche lavoro da fargli fare perché era completamente sconosciuto nei dintorni e non aveva abbastanza denaro per tornare a casa.

“Figlio mio “ rispose il vecchio “tutto il paese qui attorno è disabitato, io stesso devo recarmi in villaggi lontani per sopravvivere e persino allora spesso non trovo abbastanza per soddisfare la mia fame. Ma se vuoi metterti al servizio della vecchia strega Corva, vai diritto per tre ore oltre il ruscello che scorre a valle della mia casupola e giungerai a una collina di sabbia sul lato sinistro; lì è dove lei vive.”

Iwanich ringraziò il magro mendicante vestito di grigio per l’informazione e riprese la strada.

Dopo aver camminato per circa tre ore il principe giunse presso un tetro muro di pietra grigia; era il retro dell’edificio e non lo attrasse. Quando giunse di fronte alla casa, scoprì che era persino meno invitante perché la vecchia strega aveva circondato la sua dimora con un recinto di spuntoni su ognuno dei quali era infilato un teschio umano. In questo orribile recinto sorgeva una casetta nera che aveva solo due grandi finestre, tutte coperte di ragnatele, e una porta di ferro ammaccata.

Il principe bussò e una stridula voce di donna gli disse di entrare.

Iwanich aprì la porta e si ritrovò in una cucina annerita dal fumo, alla presenza di una vecchia orribile che si stava scaldando al fuoco le mani ossute. Il principe si offrì come servitore e la vecchia megera gli disse che ne stava proprio cercando uno e lui sembrava essere proprio la persona adatta.

Quando Iwanich chiese quale fosse il proprio lavoro e quale sarebbe stato il salario, la strega gli ordinò di seguirla e gli fece strada attraverso uno stretto e umido varco in una cantina che fungeva da scuderia. Lì lui si accorse di due cavalli neri come la pece in una stalla.

“Davanti a te” disse la vecchia “vedi una giumenta e il suo puledro; non devi fare altro che condurli nei campi ogni giorno e badare che nessuno di loro corra via da te. Se li sorveglierai per un anno intero, ti darò qualsiasi cosa tu chiederai; ma d’altro canto, se lascerai che l’uno o l’altro degli animali scappi, la tua ultima ora sarà giunta e la tua testa sarà impalata sull’ultimo spuntone del mio recinto. Gli altri spuntoni, come vedi, sono già stati adornati e i teschi appartengono a tutti i vari servi che ho avuto e che hanno fallito nel compiere ciò che avevo chiesto.”

Iwanich, il quale pensò che non potesse andar peggio di come già andava, accettò la proposta della strega.

all’alba del mattino seguente condusse nel campo in due cavalli e li riportò indietro la sera senza che avessero tentato di sfuggirgli. La strega era sulla porta e lo accolse gentilmente poi gli mise davanti un buon pasto.

Andò avanti così per un po’ di tempo e per il principe tutto andava bene. Ogni mattina presto conduceva i cavalli nei campi e li riportava a casa sani e salvi la sera.

Un giorno, mentre stava sorvegliando i cavalli, giunse in riva a un fiume e vide un grosso pesce, finito per disavventura sulla terraferma, che si sforzava di tornare nell’acqua.

Iwanich, che era dispiaciuto per la povera creatura, lo prese tra le braccia e lo gettò nel fiume. Appena il pesce si era appena di nuovo in acqua che, con grande meraviglia del principe, balzò di nuovo sulla riva e disse:

“Mio gentile benefattore, come posso ricompensarti per la tua bontà?”

“Non desidero nulla,” rispose il principe. “Sono gà contento di poterti essere stato utile.”

“Devi farmi il favore” disse il pesce “di prendere una squama dal mio corpo e conservarla con cura. Se mai avrai bisogno del mio aiuto, gettala nel fiume e io verrò subito in tuo soccorso.”

Iwanich si chinò, staccò una squama dal corpo dell’animale riconoscente, la mise via con cura e tornò a casa.

Poco tempo dopo, mentre stava andando la mattina presto nel solito pascolo con i cavalli, si accorse di uno stormo di uccelli riuniti insieme che facevano un gran baccano e svolazzavano avanti e indietro all’impazzata.

Incuriosito, Iwanich si affrettò sul posto e vide che un gran numero di corvi aveva attaccato un aquila, e sebbene l’aquila fosse grande e possente e fosse una valida combattente, alla fine era sopraffatta dal numero e stava per soccombere.

Il principe, dispiaciuto per il povero uccello, afferrò il ramo di un albero e colpì con esso i corvi; spaventati dall’inatteso assalto, volarono via, lasciando molti dei loro morti o feriti sul campo di battaglia.

Appena l’aquila si accorse di essere libera dagli aguzzini, si strappò una piuma dall’ala e, porgendola al principe, disse: “Ecco, mio gentile benefattore, prendi questa piuma come segno della mia gratitudine; se dovessi mai avere bisogno del mio aiuto, soffia in aria questa piuma e io ti aiuterò per quanto sarà in mio potere.”

Iwanich ringraziò l’uccello e, mettendo la piuma accanto alla squama, ricondusse a casa i cavalli.

Un altro giorno stava gironzolando come il solito e giunse vicino a un’aia; il posto piacque al principe e, siccome era pieno di buona erba per i cavalli, decise di trascorrere lì il resto della giornata. Proprio mentre stava seduto sotto un albero, sentì un grido vicino a sé e vide una volpe che era rimasta presa nella trappola piazzata lì del contadino.

Invano la povera bestia tentava di liberarsi; allora il buon principe andò subito in suo soccorso e liberò la volpe dalla trappola.

La volpe lo ringraziò di tutto cuore, prese due peli dalla sua folta coda e disse: “Se mai dovessi trovarti nella necessità del mio aiuto, getta questi due peli nel fuoco e in un attimo io sarò al tuo fianco, pronta a obbedirti.”

Iwanich ripose i peli di volpe con la squama e la piuma e, siccome si stava facendo buio, si affrettò a riportare a casa i cavalli.

Nel frattempo il suo servizio stava per finire, ancora tre giorni e l’anno sarebbe scaduto così lui avrebbe potuto riscuotere la ricompensa e congedarsi dalla strega.

La prima sera di questi ultimi tre giorni, quando era tornato a casa e stava mangiando la zuppa, si accorse che la vecchia stava sgattaiolando nella scuderia.

Il principe la seguì di nascosto per vedere che cosa stesse per fare. Si accovacciò sulla soglia e sentì la strega dire ai cavalli di aspettare il mattino seguente finché Iwanich fosse addormentato poi di andare a nascondersi nel fiume e di restare lì finché lei avesse detto loro di tornare; se non avessero fatto ciò che lei diceva, minacciò di picchiarli a sangue.

Quando Iwanich sentì tutto ciò, tornò nella propria stanza deciso a far sì che nulla lo inducesse ad addormentarsi il giorno seguente. Il mattino dopo condusse nei campi come il solito la giumenta e il puledro ma li legò con una corda che tenne in mano.

Dopo poche ore, grazie alle arti magiche della strega, fu sopraffatto dal sonno e la giumenta e il puledro scapparono come era stato detto loro di fare. Il principe non si svegliò finché non fu sera; quando lo fece, scoprì con orrore che i cavalli erano scomparsi. Disperato, maledisse il momento in cui si era messo al servizio della crudele strega e già vedeva la sua testa impalata sull’appuntito spuntone accanto alle altre.

Poi improvvisamente si rammentò della squama di pesce che, con la piuma dell’aquila e i peli della volpe, portava sempre con sé. Prese dalla borsa la squama e affrettandosi verso il fiume, ve la gettò dentro. In un attimo il pesce riconoscente nuotò verso la riva sulla quale si trovava Iwanich e disse: “Che cosa ordini, mio amico e benefattore?”

Il principe rispose: “Dovevo sorvegliare la giumenta e il puledro, ma sono corsi via da me e si sono nascosti nel fiume; se vuoi salvarmi la vita, riportali sulla terraferma.”

“Aspetta un momento” rispose il pesce “ e io e i miei amici li tireremo fuori presto dall’acqua.” e con queste parole la creatura scomparve nelle profondità del fiume.

Quasi immediatamente si sentì nelle acque un suono impetuoso e sibilante, le onde si infransero sulla riva, la spuma schizzò in aria e i due cavalli balzarono improvvisamente sulla terraferma, tremando e scrollandosi per la paura.

Iwanich balzò subito sul dorso della giumenta, afferrò il puledro per le briglie e si affrettò a tornare a casa di buonumore.

Quando la strega vide il principe che conduceva a casa i cavalli, a malapena poté nascondere la collera e, appena ebbe messo la cena davanti a Iwanich, sgattaiolò di nuovo nella scuderia. Il principe la seguì e la udì rimproverare aspramente gli animali per non essersi nascosti meglio. Ordinò loro di attende fino a che il mattino seguente Iwanich si fosse addormentato e poi di nascondersi nelle nuvole e di rimanervi finché lei non li avesse chiamati. Se non avessero fatto ciò che diceva, li avrebbe picchiati a sangue.

Il mattino seguente, dopo che Iwanich ebbe condotto i cavalli nei campi, cadde ancora una volta vittima del sonno magico. I cavalli subito corsero via e si nascosero fra le nuvole che calavano dalle montagne in soffici e gonfi cumuli.

Quando il principe si svegliò e scoprì che sia la giumenta che il puledro erano scomparsi, pensò subito all’aquila e, prendendo la piuma dalla borsa, la soffiò in aria.

In un attimo l’uccello planò accanto a lui e chiese: “Che cosa desideri che io faccia?”

“La mia giumenta e il mio puledro” rispose il principe “sono fuggiti via da me e si sono nascosti tra le nuvole; se vuoi salvarmi la vita, riporta da me entrambi gli animali.”

“Aspetta un minuto,” rispose l’aquila “con l’aiuto dei miei amici li riporterò presto da te.”

Con queste parole l’uccello volò in aria e scomparve tra le nuvole.

Quasi subito Iwanich vide i due cavalli che venivano ricondotti verso di lui da uno stormo di aquile di ogni dimensione. Afferrò la giumenta e il puledro e, dopo aver ringraziato l’aquila, li condusse allegramente di nuovo a casa.

La vecchia strega fu più indignata che mai quando lo vide comparire e, messagli davanti la cena, sgattaiolò nella scuderia e Iwanich sentì che maltrattava i cavalli per non essersi nascosti meglio tra le nuvole. Poi ordinò loro, appena Iwanich si fosse addormentato, di nascondersi il mattino seguente nel pollaio del re, che si trovava in un luogo solitario nella brughiera, e di rimanere lì finché li avesse chiamati. Se avessero fallito nel fare ciò che diceva, stavolta certamente li avrebbe picchiati a sangue.

Il mattino seguente il principe condusse i cavalli nei campi come il solito. Dopo che fu sopraffatto dal sonno, come gli altri giorni, la giumenta e il puledro corsero via e si nascosero nel pollaio reale.

Quando il principe si sveglio e scoprì che i cavalli se n’erano andati, decise di di rivolgersi alla volpe così, accendendo un fuoco, vi gettò dentro i due peli e in pochi istanti la volpe fu accanto a lui e gli chiese. “In che cosa posso servirti?”

“Vorrei sapere dove sia il pollaio del re.” rispose Iwanich.

“Appena a un’ora di cammino da qui.” rispose la volpe e si offrì di mostrare al principe la via.

Mentre stavano camminando, la volpe chiese che cosa volesse fare nel pollaio del re. Il principe le raccontò la disgrazia che gli era piovuta addosso e la necessità di ritrovare la giumenta e il puledro.

“Non è una cosa semplice,” rispose la volpe “però aspetta un momento. Ho un’idea. Rimani presso la porta del pollaio e aspetta lì i cavalli. Nel frattempo io mi introdurrò tra le galline attraverso un buco nel muro e darò loro la caccia così che il rumore che faranno sveglierà le sorveglianti reali e verranno a vedere quale sia la causa. Quando vedranno i cavalli, immagineranno subito che siano stati loro la causa del trambusto e li condurranno fuori. Allora tu dovrai mettere le mani sui cavalli e afferrarli.”

Tutto andò esattamente come aveva previsto la scaltra volpe. Il principe si gettò sulla giumenta, afferrò il puledro per le briglie e si affrettò verso casa.

Mentre stava cavalcando di buonumore nella brughiera, la giumenta improvvisamente disse al suo cavaliere: “Sei la prima persona che sia riuscita a superare in astuzia la vecchia strega Corva e ora potrai chiedere la ricompensa per il tuo servizio. Se prometti di non tradirmi mai, ti darò un consiglio che farai bene a seguire.”

Il principe promise di non tradire mai la sua fiducia e la giumenta continuò: “Non chiedere altra ricompensa che il mio puledro perché al mondo non ce n’è un altro simile a lui e non lo si può acquistare per amore o per denaro; può andare da un capo all’altro della terra in pochi minuti. Naturalmente l’astuta Corva farà del proprio meglio per dissuaderti dal chiedere il puledro e ti dirà che è pigro e malaticcio; non crederle e rimani saldo nella tua decisione.”

Iwanich desiderava possedere un tale cavallo e promise alla giumenta di seguire il suo consiglio.

Stavolta Corva lo ricevette nel modo più amichevole e gli mise davanti un pasto sontuoso. Appena l’ebbe finito, gli domandò che ricompensa chiedesse per l’anno di servizio.

Il principe rispose: “Niente di più e niente di meno del puledro della tua giumenta.”

La strega finse di restare stupita per la richiesta e disse che meritava molto più del puledro perché l’animale era pigro e nervoso, cieco da un occhio e, per farla breve, completamente inutile.

Ma il principe sapeva ciò che voleva e quando la vecchia strega vide che si era intestardito ad avere il puledro, disse: “Sono costretta a mantenere la promessa e a consegnarti il puledro; siccome so chi sei e che cosa vuoi, ti dirò in che modo l’animale ti sarà utile. l’uomo nel calderone di pece bollente, che hai liberato, è un mago potente; a causa della tua curiosità e della tua sconsideratezza Militza è caduta in suo potere e ha trasportato in un paese lontano lei, il suo castello e tutto ciò che le appartiene.

“Tu sei l’unica persona che può ucciderlo; di conseguenza ti teme tanto che ha mandato delle spie a sorvegliarti e esse gli riferiscono quotidianamente i tuoi movimenti.

“Quando sarai giunto da lui, guardati dl rivolgergli una sola parola o cadrai in potere dei suoi amici. Afferralo per la barba e gettalo a terra.”

Iwanich ringrazio la vecchia strega, montò sul puledro, lo spronò ai fianchi e si slanciò come un lampo nell’aria.

Si stava quasi facendo buio quando Iwanich si accorse di alcune figure in lontananza; ben presto vennero avanti e il principe allora vide che erano il mago e i suoi amici che stavano conducendo in aria un carro trainato da gufi.

Quando il mago si trovò a faccia a faccia con Iwanich, senza possibilità di fuga, gli si rivolse con finta cordialità e disse: “Tre volte mio gentile benefattore!”

Ma il principe, senza pronunciare una parola, lo afferrò per la barba e lo gettò a terra. Il quell’istante il puledro balzò sul mago e lo colpì con calci e colpi finché mori.

Allora Iwanich si ritrovò ancora una volta nel palazzo della sua sposa e Militza stessa gli si gettò tra le braccia.

Da quel momento in poi vissero felici e in pace fino alla fine dei loro giorni.

Fiaba russa raccolta da Kletke.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)