In China, as I daresay you know, the Emperor is a Chinaman, and all his courtiers are also Chinamen. The story I am going to tell you happened many years ago, but it is worth while for you to listen to it, before it is forgotten.

The Emperor's Palace was the most splendid in the world, all made of priceless porcelain, but so brittle and delicate that you had to take great care how you touched it. In the garden were the most beautiful flowers, and on the loveliest of them were tied silver bells which tinkled, so that if you passed you could not help looking at the flowers. Everything in the Emperor's garden was admirably arranged with a view to effect; and the garden was so large that even the gardener himself did not know where it ended. If you ever got beyond it, you came to a stately forest with great trees and deep lakes in it. The forest sloped down to the sea, which was a clear blue. Large ships could sail under the boughs of the trees, and in these trees there lived a Nightingale. She sang so beautifully that even the poor fisherman who had so much to do stood and listened when he came at night to cast his nets. 'How beautiful it is!' he said; but he had to attend to his work, and forgot about the bird. But when she sang the next night and the fisherman came there again, he said the same thing, 'How beautiful it is!'

From all the countries round came travellers to the Emperor's town, who were astonished at the Palace and the garden. But when they heard the Nightingale they all said, 'This is the finest thing after all!'

The travellers told all about it when they went home, and learned scholars wrote many books upon the town, the Palace, and the garden. But they did not forget the Nightingale; she was praised the most, and all the poets composed splendid verses on the Nightingale in the forest by the deep sea.

The books were circulated throughout the world, and some of them reached the Emperor. He sat in his golden chair, and read and read. He nodded his head every moment, for he liked reading the brilliant accounts of the town, the Palace, and the garden. 'But the Nightingale is better than all,' he saw written.

'What is that?' said the Emperor. 'I don't know anything about the Nightingale! Is there such a bird in my empire, and so near as in my garden? I have never heard it! Fancy reading for the first time about it in a book!'

And he called his First Lord to him. He was so proud that if anyone of lower rank than his own ventured to speak to him or ask him anything, he would say nothing but 'P!' and that does not mean anything.

'Here is a most remarkable bird which is called a Nightingale!' said the Emperor. 'They say it is the most glorious thing in my kingdom. Why has no one ever said anything to me about it?'

'I have never before heard it mentioned!' said the First Lord. 'I will look for it and find it!'

But where was it to be found? The First Lord ran up and down stairs, through the halls and corridors; but none of those he met had ever heard of the Nightingale. And the First Lord ran again to the Emperor, and told him that it must be an invention on the part of those who had written the books.

'Your Irmperial Majesty cannot really believe all that is written! There are some inventions called the Black Art!'

'But the book in which I read this,' said the Emperor, 'is sent me by His Great Majesty the Emperor of Japan; so it cannot be untrue, and I will hear the Nightingale! She must be here this evening! She has my gracious permission to appear, and if she does not, the whole Court shall be trampled under foot after supper!'

'Tsing pe!' said the First Lord; and he ran up and down stairs, through the halls and corridors, and half the Court ran with him, for they did not want to be trampled under foot. Everyone was asking after the wonderful Nightingale which all the world knew of, except those at Court.

At last they met a poor little girl in the kitchen, who said, 'Oh! I know the Nightingale well. How she sings! I have permission to carry the scraps over from the Court meals to my poor sick mother, and when I am going home at night, tired and weary, and rest for a little in the wood, then I hear the Nightingale singing! It brings tears to my eyes, and I feel as if my mother were kissing me!'

'Little kitchenmaid!' said the First Lord, 'I will give you a place in the kitchen, and you shall have leave to see the Emperor at dinner, if you can lead us to the Nightingale, for she is invited to come to Court this evening.'

And so they all went into the wood where the Nightingale was wont to sing, and half the Court went too.

When they were on the way there they heard a cow mooing.

'Oh!' said the Courtiers, 'now we have found her! What a wonderful power for such a small beast to have! I am sure we have heard her before!'

'No; that is a cow mooing!' said the little kitchenmaid. 'We are still a long way off!'

Then the frogs began to croak in the marsh. 'Splendid!' said the Chinese chaplain. 'Now we hear her; it sounds like a little church-bell!'

'No, no; those are frogs!' said the little kitchenmaid. 'But I think we shall soon hear her now!'

Then the Nightingale began to sing.

'There she is!' cried the little girl. 'Listen! She is sitting there!' And she pointed to a little dark-grey bird up in the branches.

'Is it possible!' said the First Lord. 'I should never have thought it! How ordinary she looks! She must surely have lost her feathers because she sees so many distinguished men round her!'

'Little Nightingale,' called out the little kitchenmaid, 'our Gracious Emperor wants you to sing before him!'

'With the greatest of pleasure!' said the Nightingale; and she sang so gloriously that it was a pleasure to listen.

'It sounds like glass bells!' said the First Lord. 'And look how her little throat works! It is wonderful that we have never heard her before! She will be a great success at Court.'

'Shall I sing once more for the Emperor?' asked the Nightingale, thinking that the Emperor was there.

'My esteemed little Nightingale,' said the First Lord, 'I have the great pleasure to invite you to Court this evening, where His Gracious Imperial Highness will be enchanted with your charming song!'

'It sounds best in the green wood,' said the Nightingale; but still, she came gladly when she heard that the Emperor wished it.

At the Palace everything was splendidly prepared. The porcelain walls and floors glittered in the light of many thousand gold lamps; the most gorgeous flowers which tinkled out well were placed in the corridors. There was such a hurrying and draught that all the bells jingled so much that one could not hear oneself speak. In the centre of the great hall where the Emperor sat was a golden perch, on which the Nightingale sat. The whole Court was there, and the little kitchenmaid was allowed to stand behind the door, now that she was a Court-cook. Everyone was dressed in his best, and everyone was looking towards the little grey bird to whom the Emperor nodded.

The Nightingale sang so gloriously that the tears came into the Emperor's eyes and ran down his cheeks. Then the Nightingale sang even more beautifully; it went straight to all hearts. The Emperor was so delighted that he said she should wear his gold slipper round her neck. But the Nightingale thanked him, and said she had had enough reward already. 'I have seen tears in the Emperor's eyes—that is a great reward. An Emperor's tears have such power!' Then she sang again with her gloriously sweet voice.

'That is the most charming coquetry I have ever seen!' said all the ladies round. And they all took to holding water in their mouths that they might gurgle whenever anyone spoke to them. Then they thought themselves nightingales. Yes, the lackeys and chambermaids announced that they were pleased; which means a great deal, for they are the most difficult people of all to satisfy. In short, the Nightingale was a real success.

She had to stay at Court now; she had her own cage, and permission to walk out twice in the day and once at night.

She was given twelve servants, who each held a silken string which was fastened round her leg. There was little pleasure in flying about like this.

The whole town was talking about the wonderful bird, and when two people met each other one would say 'Nightin,' and the other 'Gale,' and then they would both sigh and understand one another.

Yes, and eleven grocer's children were called after her, but not one of them could sing a note.

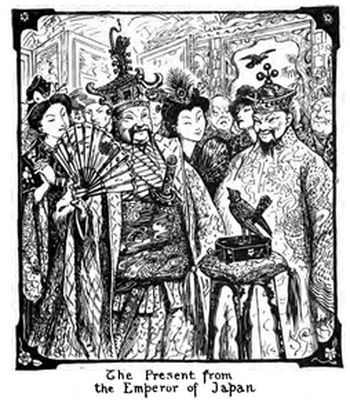

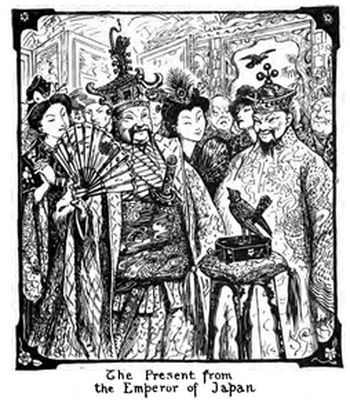

One day the Emperor received a large parcel on which was written 'The Nightingale.'

'Here is another new book about our famous bird!' said the Emperor.

But it was not a book, but a little mechanical toy, which lay in a box—an artificial nightingale which was like the real one, only that it was set all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. When it was wound up, it could sing the piece the real bird sang, and moved its tail up and down, and glittered with silver and gold. Round its neck was a little collar on which was written, 'The Nightingale of the Emperor of Japan is nothing compared to that of the Emperor of China.'

'This is magnificent!' they all said, and the man who had brought the clockwork bird received on the spot the title of 'Bringer of the Imperial First Nightingale.'

'Now they must sing together; what a duet we shall have!'

And so they sang together, but their voices did not blend, for the real Nightingale sang in her way and the clockwork bird sang waltzes.

'It is not its fault!' said the bandmaster; 'it keeps very good time and is quite after my style!'

Then the artificial bird had to sing alone. It gave just as much pleasure as the real one, and then it was so much prettier to look at; it sparkled like bracelets and necklaces. Three-and-thirty times it sang the same piece without being tired. People would like to have heard it again, but the Emperor thought that the living Nightingale should sing now—but where was she? No one had noticed that she had flown out of the open window away to her green woods.

'What shall we do!' said the Emperor.

And all the Court scolded, and said that the Nightingale was very ungrateful. 'But we have still the best bird!' they said and the artificial bird had to sing again, and that was the thirty-fourth time they had heard the same piece. But they did not yet know it by heart; it was much too difficult. And the bandmaster praised the bird tremendously; yes, he assured them it was better than a real nightingale, not only because of its beautiful plumage and diamonds, but inside as well. 'For see, my Lords and Ladies and your Imperial Majesty, with the real Nightingale one can never tell what will come out, but all is known about the artificial bird! You can explain it, you can open it and show people where the waltzes lie, how they go, and how one follows the other!'

'That's just what we think!' said everyone; and the bandmaster received permission to show the bird to the people the next Sunday. They should hear it sing, commanded the Emperor. And they heard it, and they were as pleased as if they had been intoxicated with tea, after the Chinese fashion, and they all said 'Oh!' and held up their forefingers and nodded time. But the poor fishermen who had heard the real Nightingale said: 'This one sings well enough, the tunes glide out; but there is something wanting— I don't know what!'

The real Nightingale was banished from the kingdom.

The artificial bird was put on silken cushions by the Emperor's bed, all the presents which it received, gold and precious stones, lay round it, and it was given the title of Imperial Night-singer, First from the left. For the Emperor counted that side as the more distinguished, being the side on which the heart is; the Emperor's heart is also on the left.

And the bandmaster wrote a work of twenty-five volumes about the artificial bird. It was so learned, long, and so full of the hardest Chinese words that everyone said they had read it and understood it; for once they had been very stupid about a book, and had been trampled under foot in consequence. So a whole year passed. The Emperor, the Court, and all the Chinese knew every note of the artificial bird's song by heart. Bat they liked it all the better for this; they could even sing with it, and they did. The street boys sang 'Tra-la-la-la-la,' and the Emperor sang too sometimes. It was indeed delightful.

But one evening, when the artificial bird was singing its best, and the Emperor lay in bed listening to it, something in the bird went crack. Something snapped! Whir-r-r! all the wheels ran down and then the music ceased. The Emperor sprang up, and had his physician summoned, but what could HE do! Then the clockmaker came, and, after a great deal of talking and examining, he put the bird somewhat in order, but he said that it must be very seldom used as the works were nearly worn out, and it was impossible to put in new ones. Here was a calamity! Only once a year was the artificial bird allowed to sing, and even that was almost too much for it. But then the bandmaster made a little speech full of hard words, saying that it was just as good as before. And so, of course, it WAS just as good as before. So five years passed, and then a great sorrow came to the nation. The Chinese look upon their Emperor as everything, and now he was ill, and not likely to live it was said.

Already a new Emperor had been chosen, and the people stood outside in the street and asked the First Lord how the old Emperor was. 'P!' said he, and shook his head.

Cold and pale lay the Emperor in his splendid great bed; the whole Court believed him dead, and one after the other left him to pay their respects to the new Emperor. Everywhere in the halls and corridors cloth was laid down so that no footstep could be heard, and everything was still—very, very still. And nothing came to break the silence.

The Emperor longed for something to come and relieve the monotony of this deathlike stillness. If only someone would speak to him! If only someone would sing to him. Music would carry his thoughts away, and would break the spell lying on him. The moon was streaming in at the open window; but that, too, was silent, quite silent.

'Music! music!' cried the Emperor. 'You little bright golden bird, sing! do sing! I gave you gold and jewels; I have hung my gold slipper round your neck with my own hand—sing! do sing!' But the bird was silent. There was no one to wind it up, and so it could not sing. And all was silent, so terribly silent!

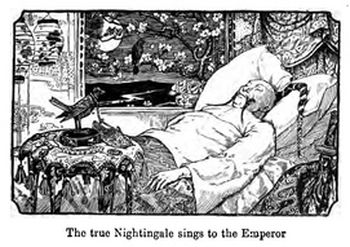

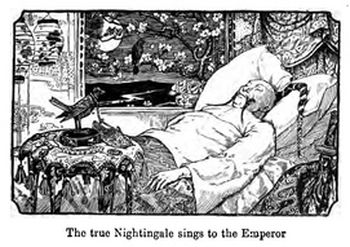

All at once there came in at the window the most glorious burst of song. It was the little living Nightingale, who, sitting outside on a bough, had heard the need of her Emperor and had come to sing to him of comfort and hope. And as she sang the blood flowed quicker and quicker in the Emperor's weak limbs, and life began to return.

'Thank you, thank you!' said the Emperor. 'You divine little bird! I know you. I chased you from my kingdom, and you have given me life again! How can I reward you?'

'You have done that already!' said the Nightingale. 'I brought tears to your eyes the first time I sang. I shall never forget that. They are jewels that rejoice a singer's heart. But now sleep and get strong again; I will sing you a lullaby.' And the Emperor fell into a deep, calm sleep as she sang.

The sun was shining through the window when he awoke, strong and well. None of his servants had come back yet, for they thought he was dead. But the Nightingale sat and sang to him.

'You must always stay with me!' said the Emperor. 'You shall sing whenever you like, and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.'

'Don't do that!' said the Nightingale. 'He did his work as long as he could. Keep him as you have done! I cannot build my nest in the Palace and live here; but let me come whenever I like. I will sit in the evening on the bough outside the window, and I will sing you something that will make you feel happy and grateful. I will sing of joy, and of sorrow; I will sing of the evil and the good which lies hidden from you. The little singing-bird flies all around, to the poor fisherman's hut, to the farmer's cottage, to all those who are far away from you and your Court. I love your heart more than your crown, though that has about it a brightness as of something holy. Now I will sing to you again; but you must promise me one thing——'

'Anything!' said the Emperor, standing up in his Imperial robes, which he had himself put on, and fastening on his sword richly embossed with gold.

'One thing I beg of you! Don't tell anyone that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be much better not to!' Then the Nightingale flew away.

The servants came in to look at their dead Emperor.

The Emperor said, 'Good-morning!'

Unknown.

L'usignolo

In Cina, come oso dire voi sappiate, l'Imperatore è un cinese, e anche tutti i suoi cortigiani sono cinesi. La storia che sto per raccontarvi è accaduta molti anni fa, ma vale la pena che la ascoltiate, prima che venga dimenticata.

Il palazzo dell'imperatore era il più splendido del mondo, tutto fatto di porcellana inestimabile, ma così fragile e delicato che bisognava star bene attenti a come lo si toccava. Nel giardino c'erano i fiori più belli, e al più bello di essi erano legati campanelli d'argento che tintinnavano, così che, se passavate, non potevate fare a meno di guardare i fiori. Tutto nel giardino dell'Imperatore era mirabilmente organizzato in modo tale da fare effetto; e il giardino era così grande che perfino il giardiniere stesso non sapeva dove finisse. Se mai foste andati oltre, sareste arrivati in ??una foresta maestosa con grandi alberi e laghi profondi. La foresta digradava verso il mare, che era di un blu limpido. Grandi navi potevano navigare sotto i rami degli alberi e in questi alberi viveva un usignolo. Cantava così bene che persino il povero pescatore che aveva così tanto da fare stava in piedi ad ascoltarlo quando veniva di notte a gettare le sue reti. 'Quanto è bello!' diceva, ma doveva badare al proprio lavoro e dimenticava l'uccello. Ma quando cantò la notte seguente e il pescatore venne di nuovo lì, disse la medesima cosa: "Com’è bello!"

Da tutti i paesi intorno arrivavano viaggiatori nella città dell'Imperatore, che rimanevano sbalorditi per il palazzo e il giardino. Ma quando sentivano l'usignolo, dicevano tutti: "Questa è la cosa più bella di tutte!"

I viaggiatori raccontavano tutto quando tornavano a casa, e dotti studiosi scrivevano molti libri sulla città, sul palazzo e sul giardino. Ma non dimenticavano l'usignolo; era elogiato più di tutto e tutti i poeti componevano splendidi versi sull'usignolo nella foresta vicino al mare profondo.

I libri furono si diffusero per il mondo e alcuni giunsero all'Imperatore. Si sedette sulla sua sedia dorata, e lesse, lesse. Annuiva con la testa ogni momento, perché gli piaceva leggere i racconti brillanti sulla città, sul palazzo e sul giardino. “Ma l'usignolo è il migliore di tutti”, leggeva.

“ Che cos'è?' disse l'imperatore. "Non so nulla dell'usignolo! C'è un uccello simile nel mio impero, e così vicino come nel mio giardino? Non l'ho mai sentito!Curioso leggerne per la prima volta in un libro!”

E chiamò il suo Primo Dignitario. Era così orgoglioso che se qualcuno di grado inferiore al suo si fosse azzardato a parlargli o chiedergli qualcosa, non avrebbe detto altro che "P!" e ciò non significa niente.

"Qui c’è un uccello straordinario che si chiama usignolo!" disse l'imperatore. "Dicono che è la cosa più gloriosa del mio regno. Perché nessuno mi ha mai detto nulla a riguardo? "

“Non l'ho mai sentito nominare prima!” disse il Primo Dignitario. “Lo cercherò e lo troverò!”

Ma dove trovarlo? Il Primo Dignitario corse su e giù per le scale, attraverso le sale e i corridoi, ma nessuno di quelli che incontrava aveva mai sentito parlare dell'usignolo. E il Primo Dignitario corse di nuovo dall'Imperatore e gli disse che doveva essere un'invenzione da parte di coloro che avevano scritto i libri.

"La vostra imperiale maestà non può davvero credere a tutto ciò che è scritto! Ci sono alcune invenzioni chiamate Arte Nera!”

“Ma il libro in cui ho letto ciò”, disse l'Imperatore, 'mi è stato mandato da Sua Maestà l'Imperatore del Giappone; quindi non può essere falso, e io sentirò l'usignolo! Deve essere qui stasera! Ha il mio grazioso permesso di comparire, e se non lo fa, l'intera Corte sarà calpestata dopo cena! '

"Tsing pe!" disse il Primo Dignitario; e correva su e giù per le scale, attraverso le sale e i corridoi, e metà della Corte correva con lui, perché non volevano essere calpestati. Tutti chiedevano del meraviglioso usignolo che tutti conoscevano al mondo, eccetto quelli della Corte.

Alla fine incontrarono una povera ragazza in cucina, che disse: "Conosco bene l'usignolo. Come canta! Ho il permesso di portare gli avanzi dai pasti della Corte alla mia povera madre malata, e quando vado a casa di notte, stanco e affaticata,e resto a riposare un po' nel bosco, allora sento il canto dell’usignolo! Mi fa venire le lacrime agli occhi e sento come se mia madre mi stesse baciando! "

"Piccola sguattera!" disse il Primo Dignitario: "Ti darò un posto in cucina, e tu andrai a vedere l'Imperatore a cena, se puoi condurci dall'usignolo, perché è stato invitato a venire a corte stasera."

E così andarono tutti nel bosco dove era solito cantare l'usignolo, e anche la metà della corte andò.

Quando furono sulla strada, sentirono una mucca che muggiva.

'Oh!' dissero i cortigiani, "ora l'abbiamo trovato! Che potere meraviglioso per una bestia così piccola! Sono sicuro che l'abbiamo già sentita prima!”

'No; è una mucca che muggisce! disse la piccola sguattera. 'Siamo ancora molto lontani!'

Poi le rane cominciarono a gracidare nella palude. 'Splendido!' disse il cappellano cinese. "Adesso lo sentiamo; è simile a una piccola campana di chiesa!”

'No, no; quelle sono rane! ' disse la piccola sguattera. "Ma penso che presto lo sentiremo!"

Poi l'usignolo cominciò a cantare.

'Eccolo!' gridò la ragazzina. 'Ascoltate! È posato qui!”E indicò un piccolo uccello grigio scuro tra i rami.

“Possibile!” disse il Primo Dignitario. 'Non avrei mai pensato! Com'è ordinario! Deve aver sicuramente perso le piume perché vede intorno a sé tanti uomini illustri!”

"Piccolo usignolo," chiamò la piccola sguattera, "il nostro grazioso imperatore vuole che tu canti davanti a lui!"

"Con il più grande piacere!" disse l'usignolo; e ha cantato così gloriosamente che era un piacere ascoltare.

"Sembrano campane di vetro!" disse il Primo Dignitario. "E guarda come funziona la sua piccola gola! È incredibile che non l'abbiamo mai sentito prima! Sarà un grande successo a corte.”

"Devo cantare ancora una volta per l'imperatore?" chiese l'usignolo, pensando che l'imperatore fosse lì.

"Mio stimato piccolo Usignolo," disse il Primo Dignitario, "ho il grande piacere di invitarti a Corte stasera, dove Sua Graziosa Altezza Imperiale sarà incantata dalla tua affascinante canzone!"

“È meglio nel bosco verde», disse l'usignolo, tuttavia venne volentieri quando sentì che l'Imperatore lo desiderava.

A Palazzo tutto era stato splendidamente preparato. Le pareti e i pavimenti in porcellana brillavano alla luce di molte migliaia di lampade d'oro; i più bei fiori tintinnanti erano stati collocati nei corridoi. C'era una tale fretta e una tale corrente che tutte le campanelle tintinnavano così tanto che ciascuno non sentiva l’altro parlare. Al centro della grande sala in cui sedeva l'Imperatore c'era un posatoio d'oro, sul quale era appollaiato l'usignolo. L'intera Corte era lì, e alla piccola sguattera fu permesso di stare dietro la porta, ora che era una cuoca di corte. Ognuno indossava gli abiti migliori e tutti guardavano verso il piccolo uccello grigio a cui l'Imperatore annuì.

L'usignolo cantò così gloriosamente che all’imperatore salirono le lacrime agli occhi dell'imperatore e gli scorsero lungo le guance. Allora l'usignolo cantò ancora più splendidamente; toccò tutti i cuori. L'Imperatore fu così contento che disse che l’usignolo avrebbe dovuto portare la sua pantofola d'oro intorno al collo. Ma l'usignolo lo ringraziò e disse che aveva già avuto abbastanza ricompense. "Ho visto le lacrime negli occhi dell'Imperatore - questa è una grande ricompensa. Le lacrime di un imperatore hanno un tale potere!” Quindi cantò di nuovo con la sua voce gloriosamente dolce.

"Èla civetteria più affascinante che abbia mai visto!" dissero tutte le dame lì intorno. E tutti presero a trattenere l'acqua in bocca perché potessero gorgogliare ogni volta che qualcuno parlava con loro. Allora si credevano usignoli. Sì, i lacchè e le cameriere dissero di essere contenti; il che significa molto, perché sono le persone più difficili da soddisfare. In breve, l'usignolo fu un vero successo.

Adesso doveva rimanere a Court adesso; aveva la sua gabbia e il permesso di uscire due volte al giorno e una volta di notte.

Gli furono dati dodici servitori, ognuno dei quali reggeva una corda di seta che era legata alla sua zampa. C'era assai poco piacere nel volare in giro così.

L'intera città parlava dell'uccello meraviglioso, e quando due persone si incontravano si diceva "Usi" e l'altra "Gnolo", e poi sospiravano e si capivano l'un l'altro.

Sì, e gli undici bambini del droghiere furono chiamati dopo di lui, ma nessuno di loro poté cantare una nota.

Un giorno l'Imperatore ricevette un grosso pacco sul quale era scritto "L'usignolo".

“Ecco un altro nuovo libro sul nostro famoso uccello!” disse l'imperatore.

Ma non era un libro, bensì un piccolo giocattolo meccanico, che giaceva in una scatola: un usignolo artificiale simile a quello reale, solo che era tutto incastonato di diamanti, rubini e zaffiri. Quando veniva caricato, poteva cantare il pezzo che cantava il vero uccello, e muovere la coda su e giù, e brillava d'argento e d'oro. Intorno al collo c'era una fascetta sulla quale era scritto: "L'usignolo dell'Imperatore del Giappone non è nulla in confronto a quello dell'Imperatore della Cina".

“È magnifico!” dissero tutti, e l'uomo che aveva portato l'uccello a orologeria ricevette sul posto il titolo di 'Portatore del Primo Usignolo Imperiale'.

“Ora devono cantare insieme; che duetto avremo!”

E così cantarono insieme, ma le loro voci non si amalgamarono perché il vero usignolo cantava a modo proprio e l'uccello a orologeria cantava i valzer.

"Non è colpa sua!" disse il direttore della banda; “tiene molto bene il tempo ed è abbastanza nel mio stile!”

Quindi l'uccello artificiale doveva cantare da solo. Dava altrettanto piacere di quello vero, e poi era molto più bello da guardare; brillava come bracciali e collane. Trentatré volte aveva cantato lo stesso pezzo senza essere stanco. Al popolo sarebbe piaciuto sentirlo di nuovo, ma l'Imperatore pensava che l'usignolo vivente avrebbe dovuto cantare ora ... ma dov'era? Nessuno si era accorto che era volato via dalla finestra aperta verso il suo verde bosco.

“Che cosa faremo!”!' disse l'imperatore.

E tutta la Corte rimproverò l’usignolo e disse che era molto ingrato. "Ma abbiamo ancora l'uccello migliore!" dissero e l'uccello artificiale dovette cantare di nuovo, e quella era la trentaquattresima volta in cui avevano sentito lo stesso pezzo. Ma loro non lo sapevano ancora a memoria; era troppo difficile. E il direttore della banda lodò enormemente l'uccello; sì, li rassicurò, era meglio di un vero usignolo, non solo per il suo bel piumaggio e per i diamanti, ma anche per il meccanismo interno. "Per dire, miei signori e signore e vostra maestà imperiale, con il vero usignolo non si può mai sapere cosa uscirà, ma tutto si sa dell'uccello artificiale! Potete spiegarlo, potete aprirlo e mostrare alla gente dove si trovino i valzer, come vadano e come seguano l’un l'altro!"

"È proprio quello che pensiamo!" dissero tutti; e il direttore della banda ricevette il permesso di mostrare l'uccello alla gente la domenica successiva. Avrebbero dovuto sentirlo sentirlo cantare, ordinò l'Imperatore. E lo sentirono, e furono contenti come se fossero stati ubriachi di tè, secondo la moda cinese, e tutti dissero "Oh!" e sollevò gli indici e annuirono. Ma i poveri pescatori che avevano ascoltato il vero usignolo dicevano: "Questo canta abbastanza bene, le melodie scivolano fuori; ma c'è qualcosa che manca... non so cosa!”

Il vero usignolo fu bandito dal regno.

L'uccello artificiale fu messo su cuscini di seta accanto letto dell'imperatore, tutti i regali che riceveva, oro e pietre preziose, si trovano intorno a esso e gli è stato dato il titolo di Imperiale Cantore notturno, Primo da sinistra. Poiché l'Imperatore considerava quel lato come il più distinto, essendo il lato in cui si trova il cuore; anche il cuore dell'Imperatore è a sinistra.

E il direttore della banda scrisse un'opera di venticinque volumi sull'uccello artificiale. Era così colta, lunga e così pieno delle più difficili parole cinesi che tutti dicevano di averlo letto e capito; perché una volta erano stati molto stupidi riguardo a un libro, e di conseguenza erano stati. Così passò un anno intero. L'imperatore, la corte e tutti i cinesi conoscevano a memoria ogni nota del canto artificiale dell'uccello, ma piaceva molto a loro per questo potevano persino cantare con esso, e così facevano. I ragazzi di strada cantavano "Tra la la-la-la-la" e anche l'imperatore cantava a volte. Era davvero delizioso.

Ma una sera, quando l'uccello artificiale stava cantando al meglio e l'Imperatore giaceva a letto ad ascoltarlo, qualcosa nell'uccello si ruppe. Qualcosa si spezzò! Whir-rr! Tutti gli ingranaggi scesero giù e poi la musica cessò. L'Imperatore balzò in piedi e fece chiamare il suo medico, ma cosa poteva fare LUI! Poi venne l'orologiaio e, dopo aver parlato ed esaminato a lungo, mise un po' in ordine l'uccello, ma disse che lo si sarebbe dovuto usare molto di rado dato che i suoi pezzi erano quasi esaurite, ed era impossibile metterlo di nuovi. Era una calamità! L’uccello artificiale poteva cantare solo una volta all'anno e anche quello era quasi troppo per esso. Poi il direttore della banda fece un piccolo discorso pieno di parole difficili, dicendo che era buono come prima. E così, naturalmente, ERA buono come prima. Così trascorsero cinque anni e poi un grande dolore colpì la nazione. I cinesi considerano tutto il loro imperatore e ora era malato e si diceva non fosse probabile che vivesse.

Era già stato scelto un nuovo imperatore e il popolo era fuori in strada e chiedeva al Primo Dignitario come stesse il vecchio imperatore.”'P!” diceva lui, e scuoteva la testa.

L’imperatore giaceva freddo e pallido nel suo splendido e grande letto; tutta la Corte lo credeva morto, e uno dopo l'altro lo lasciarono per rendere omaggio al nuovo imperatore. Ovunque nelle sale e nei corridoi era stesa stoffa per non sentire alcun rumore di passi, e tutto era immobile, molto, molto immobile. E nulla veniva a rompere il silenzio.

L'Imperatore desiderava ardentemente che venisse qualcosa ad alleviava la monotonia di questa immobilità simile alla morte. Se solo qualcuno avesse parlato con lui! Se solo qualcuno avesse potuto cantare per lui. La musica avrebbe portato via i suoi pensieri e avrebbe spezzato l'incantesimo su di lui. La luna compariva alla finestra aperta; ma anch’essa era silenziosa, completamente silenziosa.

“Musica! Musica!” gridò l'imperatore. “Tu, piccolo uccello dorato e brillante, canta! canta! Ti ho dato oro e gioielli; Ho appeso la mia pantofola d'oro al collo con le mie mani...canta!” Ma l'uccello era silenzioso. Non c'era nessuno che lo caricasse e quindi non poteva cantare. E tutto taceva, così terribilmente silenzioso!

All'improvviso arrivò alla finestra la più gloriosa esplosione di canto. Era il piccolo usignolo vivente che, seduto fuori su un ramo, aveva sentito il desiderio del suo imperatore ed era venuto a cantare per lui conforto e speranza. E mentre cantava il sangue scorreva più veloce e più veloce nelle deboli membra dell'Imperatore, e la vita cominciava a tornare.

“Grazie, grazie!” disse l'imperatore. 'Divino uccellino! Ti conosco. Ti ho cacciato dal mio regno e tu mi hai restituito la vita! Come posso ricompensarti?”

"L'avete già fatto!" disse l'usignolo. "Vi ho fatto venire le lacrime agli occhi la prima volta che ho cantato. Non lo dimenticherò mai. Sono gioielli che rallegrano il cuore di un cantante. Ma ora dormite e prendete di nuovo forza; vi canterò una ninna nanna.” E l'Imperatore cadde in un sonno profondo e dormì tranquillo mentre l’usignolo cantava.

Il sole splendeva attraverso la finestra quando si svegliò, forte e in buona salute. Nessuno dei suoi servi era ancora tornato, perché pensavano che fosse morto. Ma l'usignolo si posò e cantò per lui.

'Devi sempre stare con me!' disse l'imperatore. "Canterai quando vorrai, e romperò l'uccello artificiale in mille pezzi".

“Non fatelo!” disse l'usignolo. 'Ha fatto il suo lavoro più a lungo che poteva. Tenetelo come avete fatto! Non posso costruire il mio nido nel palazzo e vivere qui, ma lasciatemi venire quando mi piace. Mi siederò la sera sul ramo fuori dalla finestra e vi canterò qualcosa che vi farà sentire felice e grato. Canterò di gioia e di dolore; Canterò il male e il bene che si nasconde in voi. Il piccolo uccellino vola dappertutto, nella povera capanna del pescatore, nella casetta del contadino, da tutti quelli che sono lontani da voi e dalla vostra corte. Amo il vostro cuore più della vostra corona, anche se ha la luminosità di qualcosa di santo. Ora canterò di nuovo; ma dovete promettermi una cosa ..."

'”Qualsiasi cosa!”!' disse l'Imperatore, alzandosi in piedi nelle vesti imperiali, che aveva indossato da solo, e allacciandosi la spada riccamente intarsiata d'oro.

“Di una cosa vi supplico! Non dite a nessuno che avete un uccellino che vi dice tutto. Sarà molto meglio non farlo!”' Poi l'usignolo volò via.

I servi entrarono per guardare il loro imperatore morto.

L'imperatore disse: "Buongiorno!"

Origine sconosciuta.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)