The Steadfast Tin Soldier

(MP3-9'21'')

There were once upon a time five-and twenty tin-soldiers—all brothers, as they were made out of the same old tin spoon. Their uniform was red and blue, and they shouldered their guns and looked straight in front of them. The first words that they heard in this world, when the lid of the box in which they lay was taken off, were: 'Hurrah, tin-soldiers!' This was exclaimed by a little boy, clapping his hands; they had been given to him because it was his birthday, and now he began setting them out on the table. Each soldier was exactly like the other in shape, except just one, who had been made last when the tin had run short; but there he stood as firmly on his one leg as the others did on two, and he is the one that became famous.

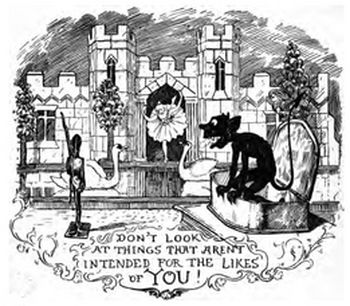

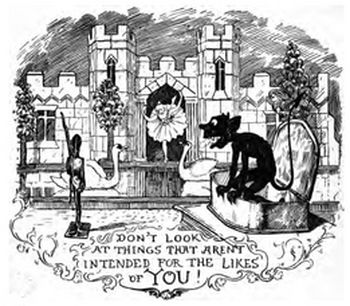

There were many other playthings on the table on which they were being set out, but the nicest of all was a pretty little castle made of cardboard, with windows through which you could see into the rooms. In front of the castle stood some little trees surrounding a tiny mirror which looked like a lake. Wax swans were floating about and reflecting themselves in it. That was all very pretty; but the most beautiful thing was a little lady, who stood in the open doorway. She was cut out of paper, but she had on a dress of the finest muslin, with a scarf of narrow blue ribbon round her shoulders, fastened in the middle with a glittering rose made of gold paper, which was as large as her head. The little lady was stretching out both her arms, for she was a Dancer, and was lifting up one leg so high in the air that the Tin-soldier couldn't find it anywhere, and thought that she, too, had only one leg.

'That's the wife for me!' he thought; 'but she is so grand, and lives in a castle, whilst I have only a box with four-and-twenty others. This is no place for her! But I must make her acquaintance.' Then he stretched himself out behind a snuff-box that lay on the table; from thence he could watch the dainty little lady, who continued to stand on one leg without losing her balance.

When the night came all the other tin-soldiers went into their box, and the people of the house went to bed. Then the toys began to play at visiting, dancing, and fighting. The tin-soldiers rattled in their box, for they wanted to be out too, but they could not raise the lid. The nut-crackers played at leap-frog, and the slate-pencil ran about the slate; there was such a noise that the canary woke up and began to talk to them, in poetry too! The only two who did not stir from their places were the Tin-soldier and the little Dancer. She remained on tip-toe, with both arms outstretched; he stood steadfastly on his one leg, never moving his eyes from her face.

The clock struck twelve, and crack! off flew the lid of the snuff-box; but there was no snuff inside, only a little black imp—that was the beauty of it.

'Hullo, Tin-soldier!' said the imp. 'Don't look at things that aren't intended for the likes of you!'

But the Tin-soldier took no notice, and seemed not to hear.

'Very well, wait till to-morrow!' said the imp.

When it was morning, and the children had got up, the Tin-soldier was put in the window; and whether it was the wind or the little black imp, I don't know, but all at once the window flew open and out fell the little Tin-soldier, head over heels, from the third-storey window! That was a terrible fall, I can tell you! He landed on his head with his leg in the air, his gun being wedged between two paving-stones.

The nursery-maid and the little boy came down at once to look for him, but, though they were so near him that they almost trod on him, they did not notice him. If the Tin-soldier had only called out 'Here I am!' they must have found him; but he did not think it fitting for him to cry out, because he had on his uniform.

Soon it began to drizzle; then the drops came faster, and there was a regular down-pour. When it was over, two little street boys came along.

'Just look!' cried one. 'Here is a Tin-soldier! He shall sail up and down in a boat!'

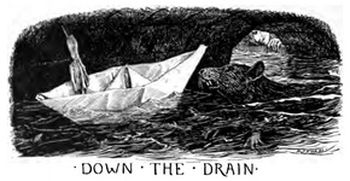

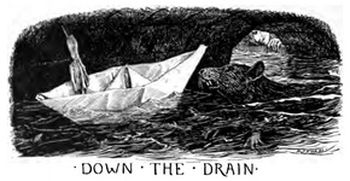

So they made a little boat out of newspaper, put the Tin-soldier in it, and made him sail up and down the gutter; both the boys ran along beside him, clapping their hands. What great waves there were in the gutter, and what a swift current! The paper-boat tossed up and down, and in the middle of the stream it went so quick that the Tin-soldier trembled; but he remained steadfast, showed no emotion, looked straight in front of him, shouldering his gun. All at once the boat passed under a long tunnel that was as dark as his box had been.

'Where can I be coming now?' he wondered. 'Oh, dear! This is the black imp's fault! Ah, if only the little lady were sitting beside me in the boat, it might be twice as dark for all I should care!'

Suddenly there came along a great water-rat that lived in the tunnel.

'Have you a passport?' asked the rat. 'Out with your passport!'

But the Tin-soldier was silent, and grasped his gun more firmly.

The boat sped on, and the rat behind it. Ugh! how he showed his teeth, as he cried to the chips of wood and straw: 'Hold him, hold him! he has not paid the toll! He has not shown his passport!'

But the current became swifter and stronger. The Tin-soldier could already see daylight where the tunnel ended; but in his ears there sounded a roaring enough to frighten any brave man. Only think! at the end of the tunnel the gutter discharged itself into a great canal; that would be just as dangerous for him as it would be for us to go down a waterfall.

Now he was so near to it that he could not hold on any longer. On went the boat, the poor Tin-soldier keeping himself as stiff as he could: no one should say of him afterwards that he had flinched. The boat whirled three, four times round, and became filled to the brim with water: it began to sink! The Tin-soldier was standing up to his neck in water, and deeper and deeper sank the boat, and softer and softer grew the paper; now the water was over his head. He was thinking of the pretty little Dancer, whose face he should never see again, and there sounded in his ears, over and over again:

Forward, forward, soldier bold!

Death's before thee, grim and cold!'

The paper came in two, and the soldier fell—but at that moment he was swallowed by a great fish.

Oh! how dark it was inside, even darker than in the tunnel, and it was really very close quarters! But there the steadfast little Tin-soldier lay full length, shouldering his gun.

Up and down swam the fish, then he made the most dreadful contortions, and became suddenly quite still. Then it was as if a flash of lightning had passed through him; the daylight streamed in, and a voice exclaimed, 'Why, here is the little Tin-soldier!' The fish had been caught, taken to market, sold, and brought into the kitchen, where the cook had cut it open with a great knife. She took up the soldier between her finger and thumb, and carried him into the room, where everyone wanted to see the hero who had been found inside a fish; but the Tin-soldier was not at all proud.  They put him on the table, and—no, but what strange things do happen in this world!—the Tin-soldier was in the same room in which he had been before! He saw the same children, and the same toys on the table; and there was the same grand castle with the pretty little Dancer. She was still standing on one leg with the other high in the air; she too was steadfast. That touched the Tin-soldier, he was nearly going to shed tin-tears; but that would not have been fitting for a soldier. He looked at her, but she said nothing.

They put him on the table, and—no, but what strange things do happen in this world!—the Tin-soldier was in the same room in which he had been before! He saw the same children, and the same toys on the table; and there was the same grand castle with the pretty little Dancer. She was still standing on one leg with the other high in the air; she too was steadfast. That touched the Tin-soldier, he was nearly going to shed tin-tears; but that would not have been fitting for a soldier. He looked at her, but she said nothing.

All at once one of the little boys took up the Tin-soldier, and threw him into the stove, giving no reasons; but doubtless the little black imp in the snuff-box was at the bottom of this too.

There the Tin-soldier lay, and felt a heat that was truly terrible; but whether he was suffering from actual fire, or from the ardour of his passion, he did not know. All his colour had disappeared; whether this had happened on his travels or whether it was the result of trouble, who can say? He looked at the little lady, she looked at him, and he felt that he was melting; but he remained steadfast, with his gun at his shoulder. Suddenly a door opened, the draught caught up the little Dancer, and off she flew like a sylph to the Tin-soldier in the stove, burst into flames—and that was the end of her! Then the Tin-soldier melted down into a little lump, and when next morning the maid was taking out the ashes, she found him in the shape of a heart. There was nothing left of the little Dancer but her gilt rose, burnt as black as a cinder.

Unknown.

Il tenace soldatino di stagno

C'erano una volta venticinque soldatini, tutti fratelli, perché erano fatti con lo stesso vecchio cucchiaio di latta. La loro uniforme era rossa e blu, portavano in spalla i loro fucili e guardarono dritto davanti a loro. Le prime parole che avevano sentito in questo mondo, quando il coperchio della scatola in cui si trovavano era stato tolto, erano: "Evviva, soldatini di piombo!" Questa fu l’esclamazione da un ragazzino, che batteva le mani; gli erano stati dati perché era il suo compleanno, e ora aveva iniziato a metterli sul tavolo. Ogni soldato aveva esattamente la medesima forma dell'altro, tranne uno solo, che era stato fatto quando il barattolo era quasi vuoto; ma stava lì si fermo su una gamba sola, come gli altri su due, ed è quello che divenne famoso.

C'erano molti altri giocattoli sul tavolo sulquale erano stati disposti, ma il più bello di tutti era un grazioso piccolo castello fatto di cartone, con le finestre attraverso le quali si poteva vedere nelle stanze. Di fronte al castello c'erano alcuni piccoli alberi che circondavano un minuscolo specchio che sembrava un lago. I cigni di cera galleggiavano e si riflettevano dentro. Era tutto molto carino; ma la cosa più bella era una piccola dama, che stava in piedi sulla porta aperta. Era ritagliata nella carta, ma indossava un abito della migliore mussola, con una sciarpa di nastro azzurro stretto attorno alle spalle, allacciata al centro da una rosa scintillante di carta dorata, grande quanto la sua testa. La damigella allungava entrambe le braccia perché era una ballerina, e stava sollevando in aria una gamba così alta che il soldatino di stagno non poteva capire dove fosse e pensò avesse anche lei una gamba sola.

‘Quella è la moglie per me!’ pensò 'ma è così splendida e vive in un castello, mentre io divido solo una scatola con altri ventiquattro. Questo non è il posto per lei! Ma devo fare la sua conoscenza.’ Quindi si distese dietro una tabacchiera che era sul tavolo; da lì poteva vedere la graziosa damigella, che continuava a stare su una gamba senza perdere l'equilibrio.

Quando venne la notte tutti gli altri soldatini di piombo entrarono nella loro scatola, e la gente della casa andò a letto. Poi i giocattoli iniziarono a farsi visita, a ballare e a combattere. I soldati di latta sbatterono nella loro scatola, perché volevano uscire, ma non potevano alzare il coperchio. Gli schiaccianoci giocavano al salto della rana e la matita ardesia correva sulla lavagna; c'era un tale rumore che il canarino si svegliò e cominciò a parlare con loro in rima! Gli unici due che non si muovevano dai loro posti erano il soldatino di stagno e la piccola ballerina. Lei rimase in punta di piedi, con entrambe le braccia distese; lui rimase fermo sulla gamba, senza mai distogliere gli occhi dal suo viso.

L'orologio la mezzanotte, e crack!volò via il coperchio della tabacchiera, ma dentro non c'era tabacco, bensì solo un piccolo diavoletto nero: quella era la sua bellezza.

"Salve, soldatino di stagno!" disse il diavoletto. "Non guardare cose che non sono destinate a persone come te!"

Ma il soldato di piombo non ci fece caso e sembrò non aver sentito.

"Molto bene, aspetta fino a domani!" disse il diavoletto.

Quando fu mattina e i bambini si furono alzati, il soldatino di piombo fu messo sulla finestra; che se fosse il vento o il diavoletto nero, non lo so, ma all'improvviso la finestra si spalancò e il soldatino di piombo cadde a testa in giù dalla finestra del terzo piano! Fu una caduta terribile, posso dirvelo! Atterrò sulla testa con la gamba in aria, il fucile incastrato tra due pietre del selciato.

La cameriera della camera dei bambini e il bambino scesero subito a cercarlo, ma, sebbene gli fossero così vicini che quasi lo calpestavano, non si accorsero di lui. Se il soldato di piombo avesse detto solo "Eccomi!" lo avrebbero trovato; ma non pensava fosse giusto che gridasse perché indossava l’uniforme.

Presto cominciò a piovigginare; poi le gocce si fecero più veloci e ci fu un acquazzone. Quando finì, arrivarono due monelli di strada.

“Guarda!'gridò uno. "Ecco un soldatino di stagno!Andrà su e giù su una barca!”

Così costruirono una piccola barca di carta di giornale, vi misero dentro il soldatino di stagno e lo fecero salire e scendere lungo un rigagnolo; entrambi i ragazzi gli correvano accanto, battendo le mani. Che grandi onde c'erano nel rigagnolo e che rapida corrente! La barchetta di carta si muoveva su e giù, e nel mezzo del rigagnolo andava così veloce che il soldatino di stagno tremava; ma rimase risoluto, non mostrò alcuna emozione, guardò dritto davanti a sé, sollevando il fucile. All'improvviso la barca passò sotto un lungo tunnel buio come la sua scatola.

'Dove starò andando ora?' si chiese. 'Povero me!! Questa è colpa del diavoletto nero! Ah, se solo la piccola dama fosse seduta accanto a me sulla barca, dovrebbe essere due volte più buio per preoccuparmi!

All'improvviso arrivò un grande topo d'acqua che viveva nel tunnel.

"Hai un passaporto?" chiese il topo. “Fuori il passaporto!”

Ma il soldatino di piombo tacque e afferrò il fucile con più fermezza.

La barca accelerò e il topo le correva dietro. Uh! come mostrava i suoi denti, mentre gridava alle schegge di legno e ai fuscelli di paglia: “Prendetelo, prendetelo! Non ha pagato il pedaggio! Non ha mostrato il passaporto!”

Ma la corrente divenne più veloce e più forte. Il soldatino di stagno poteva già vedere la luce del giorno dove finiva il tunnel; ma nelle sue orecchie suonava un ruggito tale da spaventare qualsiasi uomo coraggioso. Pensate! alla fine del tunnel il rigagnolo si gettava in un grande canale;ciò sarebbe stato altrettanto pericoloso per lui come lo sarebbe per noi scendere una cascata.

Ora era così vicino, non poteva resistere più a lungo. La barca filava, il povero soldatino di stagno si teneva il più rigido possibile: poi nessuno avrebbe potuto che si fosse tirato indietro. La barca girò tre volte, quattro volte, e si riempì d'acqua fino all'orlo, cominciò a sprofondare! Il soldatino di stagno era in piedi fino al collo nell'acqua, e la barca andava sempre più a fondo e la carta si faceva sempre più molle; ora l'acqua era sopra la sua testa. Stava pensando alla graziosa ballerino, il cui volto non avrebbe mai più rivisto, e gli risuonò nelle orecchie, ancora e ancora:

Avanti, avanti, soldatino audace!

La morte è davanti a te, triste e fredda!

Il carta si aprì in due e il soldato cadde, ma in quel momento fu inghiottito da un grande pesce.

Quanto era buio dentro, ancora più scuro che nel tunnel, ed era davvero molto stretto! Ma il tenace soldatino di stagno giaceva diritto, con il fucile in mano.

Il pesce nuotò su e ggiù, poi fece le più terribili contorsioni e improvvisamente rimase immobile. Poi fu come se un lampo di luce lo avesse attraversato; la luce del giorno irruppe e una voce esclamò: "Ecco il piccolo soldatino di stagno!" Il pesce era stato catturato, portato al mercato, venduto e portato in cucina, dove il cuoco l'aveva aperto con un grande coltello. Aveva preso il soldato tra il pollice e l'indice e lo aveva portato nella stanza, dove tutti volevano vedere l'eroe che era stato trovato in un pesce; ma il soldato di piombo non era affatto orgoglioso. Lo misero sul tavolo e ... no, ma che strane cose accadono in questo mondo! Il soldato di piombo era nella stessa stanza in cui era stato prima! Vide gli stessi bambini e gli stessi giocattoli sul tavolo; e c'era lo stesso grande castello con la graziosa ballerina. Era ancora in piedi su una gamba con l'altra in alto nell'aria, anche lei era risoluta. Questo colpì il soldatino di stagno, che stava per versare lacrime di stagno; ma non sarebbe stato adatto a un soldato. Lui la guardò, ma lei non disse nulla.

Lo misero sul tavolo e ... no, ma che strane cose accadono in questo mondo! Il soldato di piombo era nella stessa stanza in cui era stato prima! Vide gli stessi bambini e gli stessi giocattoli sul tavolo; e c'era lo stesso grande castello con la graziosa ballerina. Era ancora in piedi su una gamba con l'altra in alto nell'aria, anche lei era risoluta. Questo colpì il soldatino di stagno, che stava per versare lacrime di stagno; ma non sarebbe stato adatto a un soldato. Lui la guardò, ma lei non disse nulla.

All'improvviso uno dei ragazzini prese il soldatino di stagno e lo gettò nella stufa senza nessuna ragione; ma senza dubbio dietro a ciò vi era il diavoletto nero nella tabacchiera.

Il soldatino di piombo stava lì dentro e sentiva un caldo davvero terribile; ma non sapeva se fosse affetto dal fuoco reale o dall'ardore della sua passione. Tutto il suo colore era scomparso; se questo fosse successo durante i suoi viaggi o se fosse il risultato di un errore, chi poteva dire? Guardò la piccola dama, lei lo guardò e sentì che si stava sciogliendo; ma rimase saldo, con il fucile in spalla. All'improvviso una porta si aprì, la corrente afferrò la piccola ballerina, chee via volò come una silfide vicino al soldato di stagno nella stufa, esplose in fiamme e quella fu la sua fine! Poi il soldato di stagno si sciolse in un piccolo grumo, e quando la mattina dopo la cameriera tirò fuori le ceneri, lo trovò sotto forma di un cuore. Non era rimasto nulla della piccola ballerina se non la sua rosa dorata, bruciata, nera come la cenere.

Origine sconosciuta.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)