The Goblin and the Grocer

(MP3-3,6 MB 7' 42")

There was once a hard-working student who lived in an attic, and he had nothing in the world of his own. There was also a hard-working grocer who lived on the first floor, and he had the whole house for his own.

The Goblin belonged to him, for every Christmas Eve there was waiting for him at the grocer's a dish of jam with a large lump of butter in the middle.

The grocer could afford this, so the Goblin stayed in the grocer's shop; and this teaches us a good deal. One evening the student came in by the back door to buy a candle and some cheese; he had no one to send, so he came himself.

He got what he wanted, paid for it, and nodded a good evening to the grocer and his wife (she was a woman who could do more than nod; she could talk).

When the student had said good night he suddenly stood still, reading the sheet of paper in which the cheese had been wrapped.

It was a leaf torn out of an old book—a book of poetry

'There's more of that over there!' said the grocer 'I gave an old woman some coffee for the book. If you like to give me twopence you can have the rest.'

'Yes,' said the student, 'give me the book instead of the cheese. I can eat my bread without cheese. It would be a shame to leave the book to be torn up. You are a clever and practical man, but about poetry you understand as much as that old tub over there!'

And that sounded rude as far as the tub was concerned, but the grocer laughed, and so did the student. It was only said in fun.

But the Goblin was angry that anyone should dare to say such a thing to a grocer who owned the house and sold the best butter.

When it was night and the shop was shut, and everyone was in bed except the student, the Goblin went upstairs and took the grocer's wife's tongue. She did not use it when she was asleep, and on whatever object in the room he put it that thing began to speak, and spoke out its thoughts and feelings just as well as the lady to whom it belonged. But only one thing at a time could use it, and that was a good thing, or they would have all spoken together.

The Goblin laid the tongue on the tub in which were the old newspapers.

'Is it true,' he asked, ' that you know nothing about poetry?'

'Certainly not!' answered the tub. 'Poetry is something that is in the papers, and that is frequently cut out. I have a great deal more in me than the student has, and yet I am only a small tub in the grocer's shop.'

And the Goblin put the tongue on the coffee-mill, and how it began to grind! He put it on the butter-cask, and on the till, and all were of the same opinion as the waste-paper tub, and one must believe the majority.

'Now I will tell the student!' and with these words he crept softly up the stairs to the attic where the student lived.

There was a light burning, and the Goblin peeped through the key-hole and saw that he was reading the torn book that he had bought in the shop.

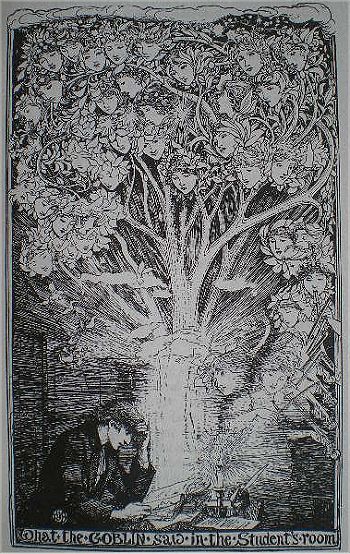

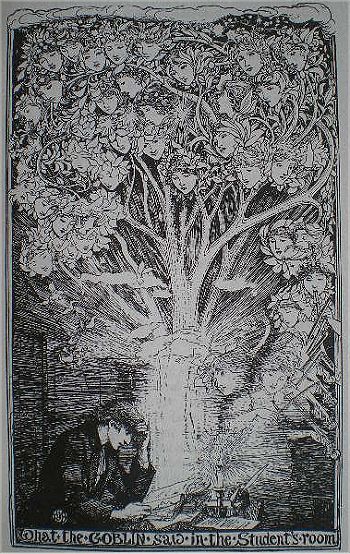

But how bright it was! Out of the book shot a streak of light which grew into a large tree and spread its branches far above the student. Every leaf was alive, and every flower was a beautiful girl's head, some with dark and shining eyes, others with wonderful blue ones. Every fruit was a glittering star, and there was a marvellous music in the student's room. The little Goblin had never even dreamt of such a splendid sight, much less seen it.

He stood on tiptoe gazing and gazing, till the candle in the attic was put out; the student had blown it out and had gone to bed, but the Goblin remained standing outside listening to the music, which very softly and sweetly was now singing the student a lullaby.

'I have never seen anything like this!' said the Goblin. 'I never expected this! I must stay with the student.'

The little fellow thought it over, for he was a sensible Goblin. Then he sighed, 'The student has no jam!'

And on that he went down to the grocer again. And it was a good thing that he did go back, for the tub had nearly worn out the tongue. It had read everything that was inside it, on the one side, and was just going to turn itself round and read from the other side when the Goblin came in and returned the tongue to its owner.

But the whole shop, from the till down to the shavings, from that night changed their opinion of the tub, and they looked up to it, and had such faith in it that they were under the impression that when the grocer read the art and drama critiques out of the paper in the evenings, it all came from the tub.

But the Goblin could no longer sit quietly listening to the wisdom and intellect downstairs. No, as soon as the light shone in the evening from the attic it seemed to him as though its beams were strong ropes dragging him up, and he had to go and peep through the key-hole. There he felt the sort of feeling we have looking at the great rolling sea in a storm, and he burst into tears. He could not himself say why he wept, but in spite of his tears he felt quite happy. How

beautiful it must be to sit under that tree with the student, but that he could not do; he had to content himself with the key-hole and be happy there!

There he stood out on the cold landing, the autumn wind blowing through the cracks of the floor. It was cold—very cold, but he first found it out when the light in the attic was put out and the music in the wood died away. Ah! then it froze him, and he crept down again into his warm corner; there it was comfortable and cosy.

When Christmas came, and with it the jam with the large lump of butter, ah! then the grocer was first with him.

But in the middle of the night the Goblin awoke, hearing a great noise and knocking against the shutters—people hammering from outside. The watchman was blowing his horn: a great fire had broken out; the whole town was in flames.

Was it in the house? or was it at a neighbour's? Where was it?

The alarm increased. The grocer's wife was so terrified that she took her gold earrings out of her ears and put them in her pocket in order to save something. The grocer seized his account books and the maid her black silk dress.

Everyone wanted to save his most valuable possession; so did the Goblin, and in a few leaps he was up the stairs and in the student's room. He was standing quietly by the open window looking at the fire that was burning in the neighbour's house just opposite. The Goblin seized the book lying on the table, put it in his red cap, and clasped it with both hands. The best treasure in the house was saved, and he climbed out on to the roof with it—on to the chimney. There he sat, lighted up by the flames from the burning house opposite, both hands holding tightly on his red cap, in which lay the treasure; and now he knew what his heart really valued most—to whom he really belonged. But when the fire was put out, and the Goblin thought it over—then—

'I will divide myself between the two,' he said. 'I cannot quite give up the grocer, because of the jam!'

And it is just the same with us. We also cannot quite give up the grocer—because of the jam.

Translated from the German of Hans Andersen.

Il goblin e il droghiere

C'era una volta un laborioso studente che viveva in una soffitta e non possedeva niente altro al mondo all'infuori di se stesso. C'era anche un droghiere gran lavoratore, che viveva al primo piano, e aveva un intero appartamento tutto per sé.

Il goblin apparteneva al droghiere perché ogni vigilia di Natale lo aspettava nella drogheria un piatto di marmellata con un grosso ricciolo di burro nel mezzo.

Il droghiere poteva permetterselo così il goblin stava nella drogheria; e questo ci mostra che era un buon affare. Una sera lo studente entrò dalla porta posteriore a comprare una candela e un po' di formaggio; non aveva nessuno mandare, così era venuto lui stesso.

Prese ciò che voleva, pagò e fece un cenno di buonasera col capo al droghiere e alla moglie (lei era una donna che avrebbe potuto fare di più che un cenno, poteva parlare).

Quando lo studente ebbe augurato la buonanotte, improvvisamente si fermò, leggendo il foglio di carta nel quale era stato avvolto il formaggio.

Era un foglio strappato da un vecchio libro - un libro di poesia.

"Là c'è n'è ancora di più!" disse il droghiere. "Ho dato un po' di caffè a una vecchia per quel libro. Se vuoi darmi due centesimi, puoi avere il resto."

"Sì," disse lo studente, "datemi il libro invece del formaggio. Posso mangiare il pane senza formaggio. Sarebbe un peccato lasciare che il libro fosse strappato. Siete un uomo intelligente e pratico, ma di poesia ne capite quanto quella vecchia vasca là!"

Ciò sembrava scortese per quanto riguardava la vasca, ma il droghiere rise e così anche lo studente. Lo aveva detto solo per scherzo.

Ma il goblin si arrabbiò perché qualcuno osava dire una cosa simile al droghiere che possedeva la casa e vendeva il burro migliore.

Quando fu notte e il negozio fu chiuso, e ognuno era a letto ad eccezione dello studente, il goblin scese di sotto e prese la lingua della moglie del droghiere. Lei non la usava quando dormiva e qualsiasi oggetto sul quale la posava, cominciava a parlare e raccontava i propri pensieri e sentimenti così bene come avrebbe potuto fare la donna alla quale apparteneva. Ma solo un oggetto alla volta la poteva usare, ed era una cosa buona, altrimenti avrebbero parlato tutti insieme.

Il goblin appoggiò la lingua sulla vasca nella quale c'erano i giornali vecchi.

"È vero," chiese, "che tu non capisci nulla di poesia?"

"Assolutamente no!" rispose la vasca. "La poesia è qualcosa che sta nei giornali e che spesso è ritagliata. Ne ho un bel po' in me più di quanta ne abbia lo studente, anche se sono solo una piccola vasca in una drogheria."

Il goblin mise la lingua sul macinino del caffè e come cominciò a macinare! La mise sul contenitore del burro, e sulla cassa, e tutti erano della medesima opinione della vasca della carta straccia e bisogna credere alla maggioranza.

"Adesso lo dirò allo studente!" e con quelle parole salì quatto quatto fino alla soffitta in cui abitava lo studente.

Vi brillava una luce e il goblin spiò attraverso il buco della serratura; vide che lui stava leggendo il libro strappato che aveva preso nella bottega.

Com'era luminoso! Dal libro emanava un fascio di luce che si era trasformato in un grande albero e allargava i rami sopra lo studente. Ogni foglia era viva e ogni fiore era una bellissima testa di fanciulla, alcune con occhi scuri e luminosi, altre con meravigliosi occhi azzurri. Ogni frutto era una stella brillante e nella stanza dello studente si diffondeva una musica meravigliosa. Il piccolo goblin non aveva mai neppure sognato una così splendida visione e tanto meno l'aveva vista.

Rimase fermo sulla punta dei piedi mirando e rimirando, finché la candela nella soffitta fu accesa; lo studente vi aveva soffiato sopra ed era andato a letto, ma il goblin rimase in piedi fuori, ascoltando la musica che sommessamente e dolcemente ora stava cantando una ninna nanna allo studente.

"Non ho mai visto nulla di simile!" disse il goblin. "Non me lo sarei mai aspettato! Devo rimanere con lo studente."

L'esserino ci pensò su, perché era un goblin sensibile. Poi sospirò: "Lo studente non ha la marmellata!"

E con ciò scese di nuovo dal droghiere. Fu un bene che fosse tornato indietro perché la vasca aveva quasi consumato la lingua. Aveva letto tutto ciò che conteneva, da un lato, e si stava proprio rigirando per leggere dall'altro lato quando il goblin tornò e restituì la lingua alla sua proprietaria.

Ma tutto il negozio, dalla cassa alle lamette da barba, da quella notte cambiò opinione sulla vasca e alzavano lo sguardo su di essa e vi riponevano tanta fiducia da aver l'impressione che, quando il droghiere leggeva critiche d'arte e di opere sul giornale della sera, venissero tutte dalla vasca.

Ma il goblin non ce la faceva più a stare tranquillo, ascoltando dabbasso la saggezza e l'intelletto. No, appena di sera la luce brillava di sera nella soffitta, gli sembrava che i suoi raggi fossero robuste funi che lo trascinavano su, e doveva andare e spiare dal buco della serratura. Lì sentiva quella specie di sensazione che proviamo guardando l'immenso mare in tempesta, e scoppiava a piangere. Non sapeva spiegarsi perché piangesse, ma, a dispetto delle lacrime, si sentiva felice.

Quanto doveva essere bello sedere sotto l'albero con lo studente, ma non avrebbe potuto farlo; doveva accontentarsi del buco della serratura ed essere felice lì!

Era sul pianerottolo freddo, il vento autunnale soffiava tra le assi del pavimento. Faceva freddo - molto freddo, ma se ne accorse quando la luce nella soffitta si spense e la musica dell'albero svanì. Ah! Allora, congelato, scese nella suo caldo cantuccio; era così confortevole e gradevole.

Quando arrivò il Natale, e con esso la marmellata con il grande ciuffo di burro, ah! allora sì che il droghiere fu il più importante per lui.

Ma nel cuore della notte il goblin si svegliò, sentendo un gran rumore e un bussare contro le imposte - gente che picchiava da fuori. Il guardiano stava suonando il corno; era scoppiato un grande incendio; l'intera città stava bruciando.

Era in casa? O era da un vicino? Dov'era?

La preoccupazione cresceva. La moglie del droghiere era così terrorizzata che si strappò gli orecchini d'oro dalle orecchie e se li mise in tasca, nel tentativo di salvare qualcosa. Il droghiere afferrò i libri contabili e la serva il vestito nero di seta.

Ognuno cercava di salvare le cose più preziose che possedeva; così fece il goblin e in pochi balzi fu alla soffitta e nella stanza dello studente. Lui se ne stava tranquillamente alla finestra aperta, guardando il fuoco che ardeva nella casa del vicino proprio di fronte. Il goblin afferrò il libro che giaceva sul tavolo, lo mise nel proprio berretto rosso e lo strinse con entrambe le mani. Il tesoro più prezioso della casa era stato salvato e lui si arrampicò sul tetto con esso - fino al comignolo. Lì sedette, illuminato dalle fiamme della casa di fronte che bruciava, entrambe le mani che tenevano stretto il berretto rosso, nel quale si trovava il tesoro; adesso sapeva davvero che cosa il suo cuore ritenesse più prezioso - a che cosa egli appartenesse realmente. Ma quando il fuoco fu domato, e il goblin ci pensò - allora -

"Mi dividerò tra i due," disse. "Non posso proprio rinunciare al droghiere, per via della marmellata!"

Ed è proprio lo stesso per noi. Anche noi non possiamo proprio rinunciare al droghiere - per via della marmellata.

Favola di Hans Christian Andersen tradotta dal tedesco

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)