Uraschimataro and the Turtle

(MP3-4,6MB;09'45'')

There was once a worthy old couple who lived on the coast, and supported themselves by fishing. They had only one child, a son, who was their pride and joy, and for his sake they were ready to work hard all day long, and never felt tired or discontented with their lot. This son's name was Uraschimataro, which means in Japanese, 'Son of the island,' and he was a fine well-grown youth and a good fisherman, minding neither wind nor weather. Not the bravest sailor in the whole village dared venture so far out to sea as Uraschimataro, and many a time the neighbours used to shake their heads and say to his parents, 'If your son goes on being so rash, one day he will try his luck once too often, and the waves will end by swallowing him up.' But Uraschimataro paid no heed to these remarks, and as he was really very clever in managing a boat, the old people were very seldom anxious about him.

One beautiful bright morning, as he was hauling his well-filled nets into the boat, he saw lying among the fishes a tiny little turtle. He was delighted with his prize, and threw it into a wooden vessel to keep till he got home, when suddenly the turtle found its voice, and tremblingly begged for its life. 'After all,' it said, 'what good can I do you? I am so young and small, and I would so gladly live a little longer. Be merciful and set me free, and I shall know how to prove my gratitude.'

Now Uraschimataro was very good-natured, and besides, he could never bear to say no, so he picked up the turtle, and put it back into the sea.

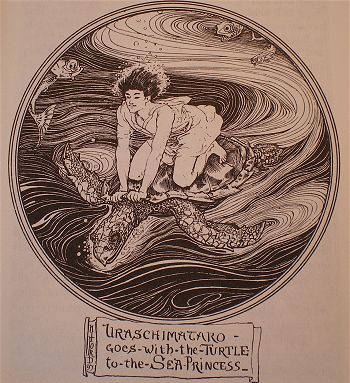

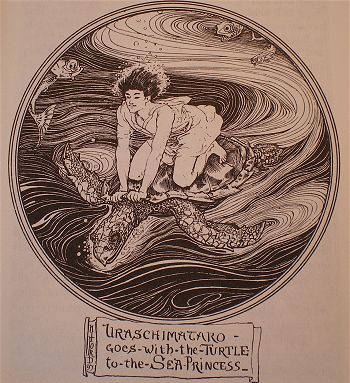

Years flew by, and every morning Uraschimataro sailed his boat into the deep sea. But one day as he was making for a little bay between some rocks, there arose a fierce whirlwind, which shattered his boat to pieces, and she was sucked under by the waves. Uraschimataro himself very nearly shared the same fate. But he was a powerful swimmer, and struggled hard to reach the shore. Then he saw a large turtle coming towards him, and above the howling of the storm he heard what it said: 'I am the turtle whose life you once saved. I will now pay my debt and show my gratitude. The land is still far distant, and without my help you would never get there. Climb on my back, and I will take you where you will.' Uraschimataro did not wait to be asked twice, and thankfully accepted his friend's help. But scarcely was he seated firmly on the shell, when the turtle proposed that they should not return to the shore at once, but go under the sea, and look at some of the wonders that lay hidden there.

Uraschimataro agreed willingly, and in another moment they were deep, deep down, with fathoms of blue water above their heads. Oh, how quickly they darted through the still, warm sea! The young man held tight, and marvelled where they were going and how long they were to travel, but for three days they rushed on, till at last the turtle stopped before a splendid palace, shining with gold and silver, crystal and precious stones, and decked here and there with branches of pale pink coral and glittering pearls. But if Uraschimataro was astonished at the beauty of the outside, he was struck dumb at the sight of the hall within, which was lighted by the blaze of fish scales.

'Where have you brought me?' he asked his guide in a low voice.

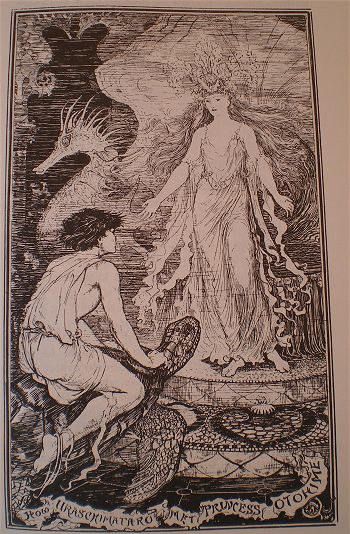

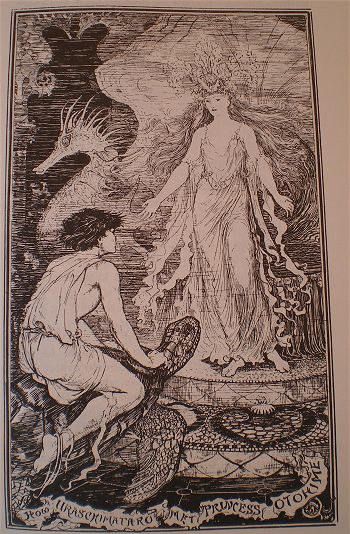

'To the palace of Ringu, the house of the sea god, whose subjects we all are,' answered the turtle. 'I am the first waiting maid of his daughter, the lovely princess Otohime, whom you will shortly see.'

Uraschimataro was still so puzzled with the adventures that had befallen him, that he waited in a dazed condition for what would happen next. But the turtle, who had talked so much of him to the princess that she had expressed a wish to see him, went at once to make known his arrival. And directly the princess beheld him her heart was set on him, and she begged him to stay with her, and in return promised that he should never grow old, neither should his beauty fade. 'Is not that reward enough?' she asked, smiling, looking all the while as fair as the sun itself. And Uraschimataro said 'Yes,' and so he stayed there. For how long? That he only knew later.

His life passed by, and each hour seemed happier than the last, when one day there rushed over him a terrible longing to see his parents. He fought against it hard, knowing how it would grieve the princess, but it grew on him stronger and stronger, till at length he became so sad that the princess inquired what was wrong. Then he told her of the longing he had to visit his old home, and that he must see his parents once more. The princess was almost frozen with horror, and implored him to stay with her, or something dreadful would be sure to happen. 'You will never come back, and we shall meet again no more,' she moaned bitterly. But Uraschimataro stood firm and repeated, 'Only this once will I leave you, and then will I return to your side for ever.' Sadly the princess shook her head, but she answered slowly, 'One way there is to bring you safely back, but I fear you will never agree to the conditions of the bargain.'

'I will do anything that will bring me back to you,' exclaimed Uraschimataro, looking at her tenderly, but the princess was silent: she knew too well that when he left her she would see his face no more. Then she took from a shelf a tiny golden box, and gave it to Uraschimataro, praying him to keep it carefully, and above all things never to open it. 'If you can do this,' she said as she bade him farewell, 'your friend the turtle will meet you at the shore, and will carry you back to me.'

Uraschimataro thanked her from his heart, and swore solemnly to do her bidding. He hid the box safely in his garments, seated himself on the back of the turtle, and vanished in the ocean path, waving his hand to the princess. Three days and three nights they swam through the sea, and at length Uraschimataro arrived at the beach which lay before his old home. The turtle bade him farewell, and was gone in a moment.

Uraschimataro drew near to the village with quick and joyful steps. He saw the smoke curling through the roof, and the thatch where green plants had thickly sprouted. He heard the children shouting and calling, and from a window that he passed came the twang of the koto, and everything seemed to cry a welcome for his return. Yet suddenly he felt a pang at his heart as he wandered down the street. After all, everything was changed. Neither men nor houses were those he once knew. Quickly he saw his old home; yes, it was still there, but it had a strange look. Anxiously he knocked at the door, and asked the woman who opened it after his parents. But she did not know their names, and could give him no news of them.

Still more disturbed, he rushed to the burying ground, the only place that could tell him what he wished to know. Here at any rate he would find out what it all meant. And he was right. In a moment he stood before the grave of his parents, and the date written on the stone was almost exactly the date when they had lost their son, and he had forsaken them for the Daughter of the Sea. And so he found that since he had deft his home, three hundred years had passed by.

Shuddering with horror at his discovery he turned back into the village street, hoping to meet some one who could tell him of the days of old. But when the man spoke, he knew he was not dreaming, though he felt as if he had lost his senses.

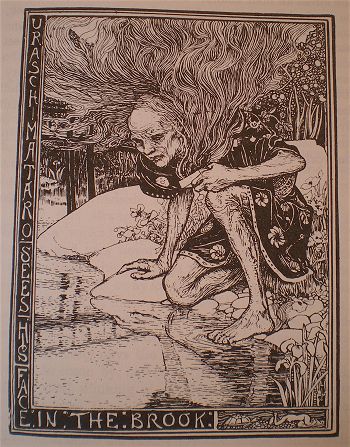

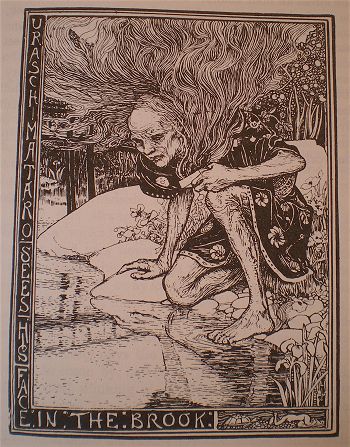

In despair he bethought him of the box which was the gift of the princess. Perhaps after all this dreadful thing was not true. He might be the victim of some enchanter's spell, and in his hand lay the counter-charm. Almost unconsciously he opened it, and a purple vapour came pouring out. He held the empty box in his hand, and as he looked he saw that the fresh hand of youth had grown suddenly shrivelled, like the hand of an old, old man. He ran to the brook, which flowed in a clear stream down from the mountain. and saw himself reflected as in a mirror. It was the face of a mummy which looked back at him.

Wounded to death, he crept back through the village, and no man knew the old, old man to be the strong handsome youth who had run down the street an hour before. So he toiled wearily back, till he reached the shore, and here he sat sadly on a rock, and called loudly on the turtle. But she never came back any more, but instead, death came soon, and set him free. But before that happened, the people who saw him sitting lonely on the shore had heard his story, and when their children were restless they used to tell them of the good son who from love to his parents had given up for their sakes the splendour and wonders of the palace in the sea, and the most beautiful woman in the world besides.

From the Japanische Marchen und Sagen, von David Brauns (Leipzig: Wilhelm Friedrich)..

Uraschimataro e la tartaruga

C'era una volta una rispettabile coppia che viveva sulla costa e si manteneva con la pesca. Avevano un solo figlio, che era il loro orgoglio e la loro soddisfazione, e per amor suo erano pronti a lavorare duramente ogni giorno e a non sentirsi mai stanchi o scontenti del loro destino. Questo figlio si chiamava Uraschimataro, che in giapponese significa 'figlio dell'isola', ed era un giovanottone alto e un ottimo pescatore, che non si curava né del vento né del maltempo. Neppure il più ardito marinaio dell'intero villaggio aveva osato avventurarsi in mare aperto così come Uraschimataro e molte volte i vicini erano soliti crollare la testa e dire ai suoi genitori "Se vostro figlio continuerà a essere così temerario, un giorno cercherà fortuna un po' troppo lontano e le onde si chiuderanno su di lui." Ma Uraschimataro non badava a questi rimproveri ed era davvero così abile nel governare la barca che molto raramente i suoi anziani genitori erano in ansia per lui.

Un meraviglioso e luminoso mattino, mentre stava trascinando le reti nella barca, vide tra i pesci una piccola tartaruga. Fu felice di quel premio e la gettò in un recipiente di legno per tenervela fino a che fosse giunto a casa, quando all'improvviso la tartaruga quando all'improvviso la tartaruga ritrovò la voce e lo supplicò tremebonda per la propria vita. "Dopo tutto," gli disse "che cosa puoi ricavare di buono da me? Sono così piccola e giovane e mi piacerebbe tanto vivere ancora un po' più a lungo. Sii misericordioso con me e lasciami libera, ed io saprò dimostrarti la mia gratitudine."

Ora Uraschimataro era assai buono di natura e inoltre non sarebbe mai stato capace di dire di no, così prese la tartarughina e la rimise in mare.

Passarono gli anni e ogni mattina Uraschimataro salpava con la barca verso il mare aperto. Un giorno però in cui stava andando verso una piccola baia tra le rocce, si alzò un violento turbine, che ridusse in pezzi la barca, e così essa fu risucchiata dalle onde. Lo stesso Uraschimataro per un pelo non ebbe lo stesso destino. Ma era un energico nuotatore e lottò duramente per raggiungere la spiaggia. Allora vide una grossa tartaruga che veniva verso di lui e al di sopra dell'ululato della tempesta sentì che diceva: "Sono la tartaruga alla quale un giorno salvasti la vita. Salderò il mio debito e ti dimostrerò la mia gratitudine. La terra è ancora troppo distante e senza il mio aiuto non la raggiungeresti mai. Arrampicati sul mio dorso e ti porterò dove vorrai." Uraschimataro non se lo fece dire due volte e pieno di riconoscenza accettò l'aiuto della sua amica. Ma si era appena sistemato saldamente sul guscio quando la tartaruga gli propose di non tornare subito verso la spiaggia, ma di andare sotto il mare e vedere alcune delle meraviglie che erano nascoste là.

Uraschimataro acconsentì volentieri e in un attimo scesero giù giù in profondità, con braccia e braccia (1) di acqua blu sulle loro teste. Oh, con quanta rapidità si lanciarono nel quieto, caldo mare! Il giovane si teneva saldo e si meravigliava di dove stessero andando e di quanto a lungo stessero viaggiando, ma dopo tre giorni si affrettarono, tanto che infine la tartaruga si fermò davanti a un meraviglioso palazzo, scintillante d'oro e d'argento, di cristallo e di pietre preziose, e ornato qua e là di rami di corallo rosa pallido e di perle lucenti. Se Uraschimataro era sbalordito dalla bellezza dell'esterno, restò ammutolito alla vista della sala interna, che era illuminata dal bagliore di squame di pesce.

"Dove mi hai condotto?" chiese a bassa voce alla propria guida.

"Nel palazzo di Ringu, la casa del dio del mare, al quale siamo tutti soggetti." Rispose la tartaruga. "Io sono la prima cameriera di sua figlia, la graziosa principessa Otohime, che tra poco vedrai."

Uraschimataro era ancora così stupefatto dell'avventura in cui era finito che aspettava con una sorta di stordimento ciò che sarebbe accaduto in seguito. La tartaruga, che aveva parlato così tanto di lui alla principessa da suscitarle il desiderio di vederlo, andò subito ad annunciare il suo arrivo. Subito la principessa vide che il proprio cuore gli apparteneva e lo pregò di restare con lei, promettendogli in cambio che non sarebbe mai invecchiato né avrebbe perso la sua bellezza. "Non è una ricompensa sufficiente?" gli chiese sorridendo, fissandolo bella come il sole. E Uraschimataro disse: "Sì" e così rimase. Per quanto tempo? Lo seppe solo più tardi.

La sua vita scorreva e ogni ora sembrava più felice della precedente, quando un giorno senti crescere una terribile nostalgia di rivedere i propri genitori. La combatté duramente, sapendo che avrebbe addolorato la principessa, ma diventava forte, sempre più forte, tanto che alla fine egli divenne così triste che la principessa volle sapere che cosa non andasse. Allora le raccontò della nostalgia che aveva di visitare la sua vecchia casa e di volere vedere i genitori ancora una volta. La principessa fu pervasa dall'orrore e lo implorò di restare con lei o gli sarebbero accadute cose terribili. "Non tornerai più indietro e non ci incontreremo mai più." gemette amaramente. Uraschimataro fu irremovibile e ripeté: "Ti lascerò solo questa volta e poi tornerò per sempre al tuo fianco." La principessa scosse mestamente la testa e rispose sottovoce: "C'è un solo modo per riportarti indietro salvo, ma temo che non accetterai mai le condizioni del patto."

"Farò qualsiasi cosa che mi riporti da te," esclamò Uraschimataro, fissandola teneramente, ma la principessa restò in silenzio: sapeva troppo bene che quando se ne fosse andato non avrebbe mai più rivisto il suo volto. Allora prese da una conchiglia una scatoletta d'oro e la diede a Uraschimataro, pregandolo di conservarla con cura e soprattutto di non aprirla mai. "Se lo farai," disse mentre gli diceva addio, "la tua amica tartaruga verrà a incontrarti sulla spiaggia e ti riporterà da me."

Uraschimataro la ringraziò di tutto cuore e promise solennemente di ubbidire al suo volere. Mise al sicuro la scatoletta nelle vesti, sedette sul dorso della tartaruga e scomparve nel mare, salutando con la mano la principessa. Nuotarono nel mare per tre giorni e per tre notti, infine Uraschimataro arrivò alla spiaggia sulla quale sorgeva la sua vecchia casa. La tartaruga gli disse addio e se ne andò in un attimo.

Uraschimataro si avvicinò al villaggio con passi rapidi e gioiosi. Vide il fumo dal tetto, e la paglia sulla quale le piante verdi erano rigogliosamente germogliate. Senti i bambini che gridavano e si chiamavano, e da una finestra davanti alla quale passò veniva il suono del koto e ogni cosa sembrava dolersi per il suo ritorno. Improvvisamente sentì una stretta al cuore mentre scendeva lungo la strada. Tutto gli appariva mutato. Né gli uomini né le case erano quelli che conosceva una volta. Improvvisamente vide la sua vecchia casa; sì, era ancora lì, ma aveva un aspetto strano. Bussò ansiosamente alla porta e chiese alla donna che gli aprì dove fossero i suoi genitori. Lei gli disse di non conoscere i loro nomi e che quindi non avrebbe potuto dargli notizie di loro.

Sempre più turbato, si precipitò al cimitero, l'unico posto che avrebbe potuto dirgli ciò che desiderava sapere. In ogni caso avrebbe potuto scoprire che cosa significasse tutto ciò. E aveva ragione. In un attimo si trovò davanti alla tomba dei genitori e la data incisa sulla pietra era esattamente quella in cui avevano perso il loro figlio, che li aveva abbandonati per la Figlia del Mare. Così scoprì che da quando aveva lasciato la propria casa erano trascorsi trecento anni.

Rabbrividendo di orrore alla scoperta, tornò nelle strade del villaggio, sperando di incontrare qualcuno che potesse raccontargli dei giorni passati. Ma quando un uomo parlò, capì che non stava sognando e si sentì come se avesse perso i sensi.

Disperato, si rammentò della scatoletta che gli aveva donato la principessa. Forse tutte quelle orribili cose non erano vere. Sarebbe potuto essere vittima di un incantesimo e avre tra le mani l'antidoto. Quasi involontariamente l'aprì e ne uscì un vapore viola. Teneva la scatoletta vuota in una mano e quando la guardò vide che la fresca mano di giovane era improvvisamente raggrinzita, come la mano di un uomo vecchissimo. Corse verso il ruscello, che scorreva con chiare acque dalla montagna, e vi si guardò riflesso come in uno specchio. Era la faccia di una mummia che lo fissava.

Colpito a morte, strisciò fino al villaggio e nessuno riconobbe nel vecchissimo uomo il giovane bello e forte che aveva percorso in fretta le strade del villaggio un'ora prima. Così ritorno indietro stancamente, finché raggiunse la spiaggia, e lì si lasciò cadere tristemente su una roccia chiamando lamentosamente la tartaruga. Ma essa non tornò più indietro e invece venne presto la morte e lo liberò. Però prima che accadesse, la gente che lo aveva visto sedere solitario sulla spiaggia, aveva udito la sua storia ed erano soliti raccontare ai loro figli, quando si mostravano irrequieti, del buon figliolo che per amore dei propri genitori aveva rinunciato per il loro bene allo splendore e alle meraviglie del palazzo nel mare e alla donna più bella che esistesse al mondo.

(1) il braccio è un'unità di misura marinara che corrisponde a metri 1,83

Da Japanische Marchen und Sagen, David von Brauns

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)