Long ago there lived two brothers, both of them very handsome, and both so very poor that they seldom had anything to eat but the fish which they caught. One day they had been out in their boat since sunrise without a single bite, and were just thinking of putting up their lines and going home to bed when they felt a little feeble tug, and, drawing in hastily, they found a tiny fish at the end of the hook.

‘What a wretched little creature!’ cried one brother. ‘However, it is better than nothing, and I will bake him with bread crumbs and have him for supper.’

‘Oh, do not kill me yet!’ begged the fish; ‘I will bring you good luck—indeed I will!’

‘You silly thing!’ said the young man; ‘I’ve caught you, and I shall eat you.’

But his brother was sorry for the fish, and put in a word for him.

‘Let the poor little fellow live. He would hardly make one bite, and, after all, how do we know we are not throwing away our luck! Put him back into the sea. It will be much better.’

‘If you will let me live,’ said the fish, ‘you will find on the sands to-morrow morning two beautiful horses splendidly saddled and bridled, and on them you can go through the world as knights seeking adventures.’

‘Oh dear, what nonsense!’ exclaimed the elder; ‘and, besides, what proof have we that you are speaking the truth?’

But again the younger brother interposed: ‘Oh, do let him live! You know if he is lying to us we can always catch him again. It is quite worth while trying.’

At last the young man gave in, and threw the fish back into the sea; and both brothers went supperless to bed, and wondered what fortune the next day would bring.

At the first streaks of dawn they were both up, and in a very few minutes were running down to the shore. And there, just as the fish had said, stood two magnificent horses, saddled and bridled, and on their backs lay suits of armour and under-dresses, two swords, and two purses of gold.

‘There!’ said the younger brother. ‘Are you not thankful you did not eat that fish? He has brought us good luck, and there is no knowing how great we may become! Now, we will each seek our own adventures. If you will take one road I will go the other.’

‘Very well,’ replied the elder; ‘but how shall we let each other know if we are both living?’

‘Do you see this fig-tree?’ said the younger. ‘Well, whenever we want news of each other we have only to come here and make a slit with our swords in the back. If milk flows, it is a sign that we are well and prosperous; but if, instead of milk, there is blood, then we are either dead or in great danger.’

Then the two brothers put on their armour, buckled their swords, and pocketed their purees; and, after taking a tender farewell of each other, they mounted their horses and went their various ways.

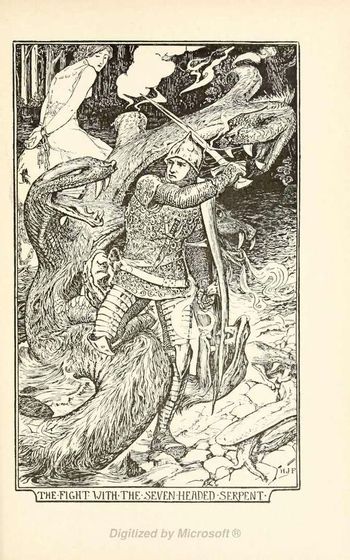

The elder brother rode straight on till he reached the borders of a strange kingdom. He crossed the frontier, and soon found himself on the banks of a river; and before him, in the middle of the stream, a beautiful girl sat chained to a rock and weeping bitterly. For in this river dwelt a serpent with seven heads, who threatened to lay waste the whole land by breathing fire and flame from his nostrils unless the king sent him every morning a man for his breakfast. This had gone on so long that now there were no men left, and he had been obliged to send his own daughter instead, and the poor girl was waiting till the monster got hungry and felt inclined to eat her.

When the young man saw the maiden weeping bitterly he said to her, ‘What is the matter, my poor girl?’

‘Oh!’ she answered, ‘I am chained here till a horrible serpent with seven heads comes to eat me. Oh, sir, do not linger here, or he will eat you too.’

‘I shall stay,’ replied the young man, ‘for I mean to set you free.’

‘That is impossible. You do not know what a fearful monster the serpent is; you can do nothing against him.’

‘That is my affair, beautiful captive,’ answered he; ‘only tell me, which way will the serpent come?’

‘Well, if you are resolved to free me, listen to my advice. Stand a little on one side, and then, when the serpent rises to the surface, I will say to him, “O serpent, to-day you can eat two people. But you had better begin first with the young man, for I am chained and cannot run away.” When he hears this most likely he will attack you.’

So the young man stood carefully on one side, and by-and-bye he heard a great rushing in the water; and a horrible monster came up to the surface and looked out for the rock where the king’s daughter was chained, for it was getting late and he was hungry.

But she cried out, ‘O serpent, to-day you can eat two people. And you had better begin with the young man, for I am chained and cannot run away.’

Then the serpent made a rush at the youth with wide open jaws to swallow him at one gulp, but the young man leaped aside and drew his sword, and fought till he had cut off all the seven heads. And when the great serpent lay dead at his feet he loosed the bonds of the king’s daughter, and she flung herself into his arms and said, ‘You have saved me from that monster, and now you shall be my husband, for my father has made a proclamation that whoever could slay the serpent should have his daughter to wife.’

But he answered, ‘I cannot become your husband yet, for I have still far to travel. But wait for me seven years and seven months. Then, if I do not return, you are free to marry whom you will. And in case you should have forgotten, I will take these seven tongues with me so that when I bring them forth you may know that I am really he who slew the serpent.’

So saying he cut out the seven tongues, and the princess gave him a thick cloth to wrap them in; and he mounted his horse and rode away.

Not long after he had gone there arrived at the river a slave who had been sent by the king to learn the fate of his beloved daughter. And when the slave saw the princess standing free and safe before him, with the body of the monster lying at her feet, a wicked plan came into his head, and he said, ‘Unless you promise to tell your father it was I who slew the serpent, I will kill you and bury you in this place, and no one will ever know what befell.’

What could the poor girl do? This time there was no knight to come to her aid. So she promised to do as the slave wished, and he took up the seven heads and brought the princess to her father.

Oh, how enchanted the king was to see her again, and the whole town shared his joy!

And the slave was called upon to tell how he had slain the monster, and when he had ended the king declared that he should have the princess to wife.

But she flung herself at her father’s feet, and prayed him to delay. ‘You have passed your royal word, and cannot go back from it Yet grant me this grace, and let seven years and seven months go by before you wed me. When they are over, then I will marry the slave.’ And the king listened to her, and seven years and seven months she looked for her bridegroom, and wept for him night and day.

All this time the young man was riding through the world, and when the seven years and seven months were over he came back to the town where the princess lived—only a few days before the wedding. And he stood before the king, and said to him: ‘Give me your daughter, O king, for I slew the seven-headed serpent. And as a sign that my words are true, look on these seven tongues, which I cut from his seven heads, and on this embroidered cloth, which was given me by your daughter.’

Then the princess lifted up her voice and said, ‘Yes, dear father, he has spoken the truth, and it is he who is my real bridegroom. Yet pardon the slave, for he was sorely tempted.’

But the king answered, ‘Such treachery can no man pardon. Quick, away with him, and off with his head!’

So the false slave was put to death, that none might follow in his footsteps, and the wedding feast was held, and the hearts of all rejoiced that the true bridegroom had come at last.

These two lived happy and contentedly for a long while, when one evening, as the young man was looking from the window, he saw on a mountain that lay out beyond the town a great bright light.

‘What can it be?’ he said to his wife.

‘Ah! do not look at it,’ she answered, ‘for it comes from the house of a wicked witch whom no man can manage to kill.’ But the princess had better have kept silence, for her words made her husband’s heart burn within him, and he longed to try his strength against the witch’s cunning. And all day long the feeling grew stronger, till the next morning he mounted his horse, and in spite of his wife’s tears, he rode off to the mountain.

The distance was greater than he thought, and it was dark before he reached the foot of the mountain; indeed, he could not have found the road at all had it not been for the bright light, which shone like the moon on his path. At length he came to the door of a fine castle, which had a blaze streaming from every window. He mounted a flight of steps and entered a hall where a hideous old woman was sitting on a golden chair.

She scowled at the young man and said, ‘With a single one of the hairs of my head I can turn you into stone.’

‘Oh, what nonsense!’ cried he. ‘Be quiet, old woman. What could you do with one hair?’ But the witch pulled out a hair and laid it on his shoulder, and his limbs grew cold and heavy, and he could not stir.

Now at this very moment the younger brother was thinking of him, and wondering how he had got on during all the years since they had parted. ‘I will go to the fig-tree,’ he said to himself, ‘to see whether he is alive or dead.’ So he rode through the forest till he came where the fig-tree stood, and cut a slit in the bark, and waited. In a moment a little gurgling noise was heard, and out came a stream of blood, running fast. ‘Ah, woe is me!’ he cried bitterly. ‘My brother is dead or dying! Shall I ever reach him in time to save his life?’ Then, leaping on his horse, he shouted, ‘Now, my steed, fly like the wind!’ and they rode right through the world, till one day they came to the town where the young man and his wife lived. Here the princess had been sitting every day since the morning that her husband had left her, weeping bitter tears, and listening for his footsteps. And when she saw his brother ride under the balcony she mistook him for her own husband, for they were so alike that no man might tell the difference, and her heart bounded, and, leaning down, she called to him, ‘At last! at last! how long have I waited for thee!’ When the younger brother heard these words he said to himself, ‘So it was here that my brother lived, and this beautiful woman is my sister-in-law,’ but he kept silence, and let her believe he was indeed her husband. Full of joy, the princess led him to the old king, who welcomed him as his own son, and ordered a feast to be made for him. And the princess was beside herself with gladness, but when she would have put her arms round him and kissed him he held up his hand to stop her, saying, ‘Touch me not,’ at which she marvelled greatly.

In this manner several days went by. And one evening, as the young man leaned from the balcony, he saw a bright light shining on the mountain.

‘What can that be?’ he said to the princess.

‘Oh, come away,’ she cried; ‘has not that light already proved your bane? Do you wish to fight a second time with that old witch?’

He marked her words, though she knew it not, and they taught him where his brother was, and what had befallen him. So before sunrise he stole out early, saddled his horse, and rode off to the mountain. But the way was further than he thought, and on the road he met a little old man who asked him whither he was going.

Then the young man told him his story, and added. ‘Somehow or other I must free my brother, who has fallen into the power of an old witch.’

‘I will tell you what you must do,’ said the old man. ‘The witch’s power lies in her hair; so when you see her spring on her and seize her by the hair, and then she cannot harm you. Be very careful never to let her hair go, bid her lead you to your brother, and force her to bring him back to life. For she has an ointment that will heal all wounds, and even wake the dead. And when your brother stands safe and well before you, then cut off her head, for she is a wicked woman.’

The young man was grateful for these words, and promised to obey them. Then he rode on, and soon reached the castle. He walked boldly up the steps and entered the hall, where the hideous old witch came to meet him. She grinned horribly at him, and cried out, ‘With one hair of my head I can change you into stone.’

‘Can you, indeed?’ said the young man, seizing her by the hair. ‘You old wretch! tell me what you have done with my brother, or I will cut your head off this very instant.’ Now the witch’s strength was all gone from her, and she had to obey.

‘I will take you to your brother,’ she said, hoping to get the better of him by cunning, ‘but leave me alone. You hold me so tight that I cannot walk.’

‘You must manage somehow,’ he answered, and held her tighter than ever. She led him into a large hall filled with stone statues, which once had been men, and, pointing out one, she said, ‘There is your brother.’

The young man looked at them all and shook his head. ‘My brother is not here. Take me to him, or it will be the worse for you.’ But she tried to put him off with other statues, though it was no good, and it was not until they had reached the last hall of all that he saw his brother lying on the ground.

‘That is my brother,’ said he. ‘Now give me the ointment that will restore him to life.’

Very unwillingly the old witch opened a cupboard close by filled with bottles and jars, and took down one and held it out to the young man. But he was on the watch for trickery, and examined it carefully, and saw that it had no power to heal. This happened many times, till at length she found it was no use, and gave him the one he wanted. And when he had it safe he made her stoop down and smear it over his brother’s face, taking care all the while never to loose her hair, and when the dead man opened his eyes the youth drew his sword and cut off her head with a single blow. Then the elder brother got up and stretched himself, and said, ‘Oh, how long I have slept! And where am I?’

‘The old witch had enchanted you, but now she is dead and you are free. We will wake up the other knights that she laid under her spells, and then we will go.’

This they did, and, after sharing amongst them the jewels and gold they found in the castle, each man went his way. The two brothers remained together, the elder tightly grasping the ointment which had brought him back to life.

They had much to tell each other as they rode along, and at last the younger man exclaimed, ‘O fool, to leave such a beautiful wife to go and fight a witch! She took me for her husband, and I did not say her nay.’

When the elder brother heard this a great rage filled his heart, and, without saying one word, he drew his sword and slew his brother, and his body rolled in the dust. Then he rode on till he reached his home, where his wife was still sitting, weeping bitterly. When she saw him she sprang up with a cry, and threw herself into his arms. ‘Oh, how long have I waited for thee! Never, never must you leave me any more!’

When the old king heard the news he welcomed him as a son, and made ready a feast, and all the court sat down. And in the evening, when the young man was alone with his wife, she said to him, ‘Why would you not let me touch you when you came back, but always thrust me away when I tried to put my arms round you or kiss you?’

Then the young man understood how true his brother had been to him, and he sat down and wept and wrung his hands because of the wicked murder that he had done. Suddenly he sprang to his feet, for he remembered the ointment which lay hidden in his garments, and he rushed to the place where his brother still lay. He fell on his knees beside the body, and, taking out the salve, he rubbed it over the neck where the wound was gaping wide, and the skin healed and the sinews grew strong, and the dead man sat up and looked round him. And the two brothers embraced each other, and the elder asked forgiveness for his wicked blow; and they went back to the palace together, and were never parted any more.

Sicilianische Mahrchen. L. Gonzenbach.

I due fratelli

Tanto tempo fa c’erano due fratelli, entrambi molto belli e così poveri che raramente avevano qualcosa da mangiare se non il pesce che pescavano. Un giorno erano stati sulla barca fino al tramonto senza che niente abboccasse e stavano proprio pensando di metter via le lenze e andare a casa a letto quando sentirono un debolissimo strattone e, trascinando rapidamente la lenza, trovarono un pesciolino all’amo.

“Che miserabile esserino!” gridò un fratello “In ogni modo è meglio di niente e lo cucinerò con il pangrattato e ci ceneremo.”

“No, non uccidetemi!” pregò il pesce “Vi porterò fortuna… lo farò davvero!”

“Sciocco!” disse il ragazzo “Ti ho catturato e ti mangerò.”

Ma il fratello era dispiaciuto per il pesce e parlò in suo favore.

“Lasciamo vivere il poverino. Ne ricaveremmo a malapena un morso e dopotutto come possiamo sapere se non stiamo dando un calcio alla fortuna! Ributtiamolo in mare, sarà molto meglio.”

“Se mi lascerete vivere,” disse il pesce, “domattina troverete sulla spiaggia due cavalli splendidamente sellati e bardati, sui quali potrete andare per il mondo come cavalieri in cerca di avventure.”

“Povero me, che sciocchezza!” esclamò il maggiore “E, inoltre, che prova abbiamo che tu stia dicendo la verità?”

Ma di nuovo il fratello minore si intromise: “Lasciamolo vivere! Sai che se sta mentendo, potremo sempre catturarlo di nuovo. Vale la pena di tentare.”

Alla fine il ragazzo ebbe la meglio e gettò il pesce in mare; entrambi i fratelli andarono a letto senza cena e si chiesero che sorte avrebbe riservato loro il giorno seguente.

Alle prime luci dell’alba erano entrambi alzati e in pochi minuti stavano correndo verso la spiaggia. E là, proprio come aveva detto il pesce, stavano due magnifici cavalli, sellati e bardati, e sul dorso avevano armature complete di cotta, due spade e due borse piene d’oro.

“Là!” disse il fratello più giovane. “Non sei grato di di non aver mangiato il pesce? Ci ha portato fortuna e non possiamo sapere quali cose grandiose ci possano capitare! Ora andremo ciascuno in cerca della propria avventura. Se tu prenderai una strada, io andrò per l’altra.”

"Molto bene,” rispose il fratello maggiore, “ma ma come potremo sapere l’uno l’altro se entrambi saremo vivi?”

“Vedi quell’albero di fico?” disse il più giovane. “Ebbene, ogni volta in cui vorremo notizie l’uno dell’altro, dovremo solo venire qui e incidervi una tacca con le spade. Se ne scaturirà latte, sarà segno che siamo entrambi in buona salute e ricchi; se invece del latte ne scaturirà sangue, vorrà dire che l’uno o l’altro sarà morto o in grave pericolo.”

Poi i due fratelli indossarono le armature, cinsero le spade e intascarono i loro averi e, dopo un tenero commiato, montarono a cavallo e presero strade diverse.

Il fratello maggiore cavalcò finché raggiunse i confini di uno strano regno. Ne varcò la frontiera e ben presto si trovò sulle rive di un fiume; davanti a lui, in mezzo alla corrente, c’era una bella fanciulla incatenata a una roccia e stava piangendo amaramente. Dovete sapere che il quel fiume dimorava un serpente con sette teste il quale minacciava di ridurre a un deserto l’intero territorio soffiando fuoco e fiamme dalle narici a meno che il re non gli mandasse ogni mattina un uomo per colazione. La faccenda era andata avanti tanto a lungo che adesso non erano rimasti più uomini e lui era stato costretto a mandare in vece la propria figlia e la povera ragazza stava aspettando finché il mostro giungesse fosse affamato e si sentisse propenso a mangiare lei.

Quando il giovane vide la ragazza che piangeva amaramente, le disse: “Che cosa c’è, mia povera ragazza?”

Lei rispose: “Sono incatenata qui finché un orribile serpente con sette teste verrà a mangiarmi. Oh, messere, non indugiate qui o sarete divorato anche voi.”

“Resterò,”rispose il ragazzo, “perché intendo liberarvi.”

“È impossibile. Non sapete che mostro spaventoso sia il serpente; non potete farcela contro di esso.”

“È un mio problema, bella prigioniera,” rispose il ragazzo, “solo ditemi, da dove verrà il serpente?”

“Ebbene, se siete deciso a liberarmi, ascoltate il mio consiglio. State un po’ in disparte e allora, quando il serpente salirà in superficie, io gli dirò: ‘O serpente, oggi puoi mangiare due persone. Ma faresti meglio a cominciare prima con il ragazzo perché io sono incatenata e non posso correre via.’ Quando sentirà queste parole, assai probabilmente vi attaccherà.”

Così il ragazzi rimase all’erta in disparte e di lì a poco udì un gran ribollio nell’acqua e un orribile mostro venne in superficie e guardò verso la roccia alla quale era incatenata la figlia del re perché si stava facendo tardi ed era affamato.

Ma lei gridò: “O serpente, oggi puoi mangiare due persone. E faresti meglio a cominciare con il ragazzo perché io sono incatenata e non posso correre via.”

Allora il serpente si slanciò verso il ragazzo con le fauci spalancate per divorarlo, ma lui balzò di lato, estrasse la spada e combatté finché ebbe tagliato tutte e sette le teste. E quando il grande serpente giacque morto ai suoi piedi, sciolse le catene della figlia del re che si gettò tra le sue braccia, dicendo: “Mi avete salvata dal mostro e adesso diventerete mio marito perché mio padre ha proclamato che chiunque avesse ucciso il serpente avrebbe avuto in sposa sua figlia.”

Però lui rispose: “Non posso ancora diventare vostro marito perché devo ancora viaggiare lontano. Aspettatemi per sette anni e sette mesi. Allora, se non sarò ritornato, sarete libera di sposare chiunque vogliate. E in caso possiate dimenticarvelo, prenderò con me queste sette lingue così che, quando le esibirò, voi possiate sapere che sono proprio colui che uccise il serpente.”

Così dicendo, tagliò le sette lingue e la principessa gli diede un panno spesso in cui avvolgerle; il ragazzo montò a cavallo e se ne andò.

Dopo poco che se n’era andato, giunse al fiume uno schiavo che era stato mandato dal re per conoscere la sorte dell’amata figlia. Quando lo schiavo si vide davanti la principessa sana e salva, con il copro del mostro che giaceva ai suoi piedi, escogitò un piano malvagio e disse: “Se non promette di dire a vostro padre che sono colui che ha ucciso il serpente, vi ucciderò e vi brucerò sul posto e nessuno saprà mai che cosa vi sia accaduto.”

Che cosa poteva fare la povera ragazza? Stavolta non c’era nessun cavaliere che venisse in suo soccorso. Così promise di fare come voleva lo schiavo e lui prese le sette teste e portò la principessa dal padre.

Come fu felice il re di vederla di nuovo e l’intera città gioì con lui!

Allo schiavo fu chiesto di raccontare come avesse ucciso il mostro e quando ebbe terminato, il re dichiarò che avrebbe avuto in moglie la principessa.

Lei però si gettò ai piedi del padre e lo pregò di rinviare. “Avete dato la vostra regale parola e non potete rimangiarla tuttavia vi chiedo di concedermi questa grazia, lasciate passare sette anni e sette mesi prima di darmi in sposa. Quando saranno trascorsi, allora sposerò lo schiavo.” Il re le diede ascolto e per sette anni e sette mesi lei aspettò il promesso sposo e pianse per lui notte e giorno.

In tutto questo tempo il ragazzo stava cavalcando per il mondo e, quando furono trascorsi i sette anni e i sette mesi, fece ritorno nella città in cui viveva la principessa – solo pochi giorni prima delle nozze. Si presentò al re e gli disse: “Datemi vostra figlia, maestà, perché ho ucciso il serpente a sette teste. Come prova che le mie parole sono veritiere, guardate le sette lingue che ho tagliato dalle sette teste, avvolte in questo panno che mi è stato dato da vostra figlia.”

Allora la principessa alzò la voce e disse: “Sì, caro padre, dice la verità e lui è il mio vero sposo. Tuttavia perdonate lo schiavo perché è stato messo a dura prova.”

Ma il re rispose: “Una simile falsità non può essere perdonata. Svelti, portatelo via e tagliategli la testa!”

Così lo schiavo bugiardo fu messo a morte, così che nessuno seguisse il suo esempio e fu allestita la festa di nozze mentre i cuori di ognuno gioivano per la venuta del vero sposo.

I due vissero a lungo felici e contenti quando una sera, mentre il ragazzo stava guardando dalla finestra, vide una grande e intensa luce sulla montagna che sorgeva oltre la città.

“Che cosa può essere?” chiese alla moglie.

“Non guardarla,” rispose lei, “perché proviene dalla casa di una malvagia strega che nessun uomo riesce a uccidere.” la principessa avrebbe fatto meglio a tacere perché le sue parole infiammarono il cuore del marito, che provò il desiderio di misurare la propria forza contro l’astuzia della strega. Per tutto il giorno il suo desiderio si fece sempre più forte finché il mattino seguente montò a cavallo e, nonostante le lacrime della moglie, galoppò verso la montagna.

La distanza era maggiore di quanto pensasse e si fece buio prima che giungesse ai piedi della montagna; in effetti non avrebbe potuto trovare la strada se non fosse stato per l’intensa luce, che brillava come la luna sul suo sentiero. Infine giunse alla porta dei un bel castello, ciascuna delle cui finestre emanava un bagliore. Salì una serie di gradini e entrò in una sala in cui un’orribile vecchia stava seduta su una scranna d’oro. Aggrottò le ciglia rivolta al ragazzo e disse: “Con un solo capello della mia testa posso trasformarti in pietra.”

“Che sciocchezza!” esclamò il ragazzo. “Stai buona, vecchia. Che cosa potresti fare con un capello?” Ma la strega si strappò un capello e glielo pose su una spalla e le sue membra si fecero fredde e pesanti e non poté muoversi.

Proprio in quel momento il fratello minore stava pensando a lui e si stava domandando che ne fosse stato di lui durante tutti quegli anni in cui erano stati divisi. ‘Andrò all’albero di fichi,’ disse tra sé, ‘per vedere se sia vivo o morto.’ così cavalcò attraverso la foresta finché giunse nel luogo in cui sorgeva l’albero di fichi, fece un’incisione nella corteccia e attese. In un istante si sentì un rumorino gorgogliante e ne scaturì un rivolo di sangue che scorreva veloce. “Ohimè!” pianse amaramente, “Mio fratello è morto o sta morendo! Riuscirò a raggiungerlo in tempo per salvargli la vita?” Poi, balzando a cavallo, gridò: “Ora, mio destriero, vola come il vento!” e cavalcò per il mondo finché un giorno giunse nella città in cui vivevano il ragazzo e sua moglie. Lì la principessa stava seduta ogni giorno sin dal mattino in attesa che il marito tornasse, piangendo lacrime amare e ascoltando per udire il rumore dei suoi passi. Quando vide suo fratello cavalcare sotto il balcone, lo scambiò per il marito perché si somigliavano tanto che nessuno avrebbe potuto vedere la differenza, e il suo cuore sobbalzò e , affrettandosi a scendere, gli gridò: “Finalmente! Finalmente! Quanto a lungo ti ho atteso!” Quando il fratello minore udì queste parole, si disse: ‘Così è qui che mio fratello viveva e questa splendida donna è mia cognata.’ ma rimase in silenzio e le lasciò credere di essere davvero suo marito. Piena di gioia la principessa lo condusse dal vecchio re, il quale lo accolse come un figlio e ordinò che fosse approntato un banchetto per lui. La principessa gli stava accanto con gioia, ma quando volle abbracciarlo e baciarlo, lui alzò la mano per fermarla, dicendo: “Non toccarmi.” al che lei si meravigliò grandemente.

In questo modo trascorsero vari giorni. Una sera, mentre il ragazzo era affacciato al balcone, vide una luce radiosa scintillare sulla montagna.

“Che cosa può essere?” chiese alla principessa.

“Vieni via!” gridò lei, “quella luce non ha già provocato la tua rovina? Desideri

lottare una seconda volta con la vecchia strega?” Lui ascoltò bene quelle parole, sebbene lei non capisse, e gli rivelarono dove fosse suo fratello e che cosa gli fosse accaduto. Così sgattaiolò via prima dell’alba, sellò il cavallo e cavalcò verso la montagna. Ma la strada era assai più lunga di quanto pensasse e sul tragitto incontrò un vecchio che gli chiese dove stesse andando.

Allora il ragazzo le raccontò la propria storia e aggiunse : “In un modo o nell’altro devo liberare mio fratello che è caduto sotto il potere di una vecchia strega.”

“Ti dirò che cosa devi fare.” disse il vecchio. “Il potere della strega sta nei suoi capelli; così quando la vedrai, gettati addosso a lei e afferrala per i capelli e allora lei non potrà farti del male. Stai bene attento a non lasciar andare i suoi capelli, ordinale di condurti da tuo fratello e obbligala a a restituirgli la vita. Lei possiede un unguento che sana ogni ferita e persino risveglia i morti. Quando tuo fratello sarà di nuovo sano e salvo davanti a te, tagliale la testa perché è una donna malvagia.”

Il ragazzo fu grato per quelle parole e promise di obbedire. Poi cavalcò via e ben presto raggiunse il castello. Salì baldanzosamente gli scalini ed entrò nella sala in cui l’orribile vecchia gli venne incontro. Gli mostrò un ghigno orrendo e gridò: “Con uno dei miei capelli posso trasformarti in pietra.”

“Lo puoi davvero?” disse il ragazzo, afferrandola per i capelli. “Vecchia miserabile! Dimmi che ne hai fatto di mio fratello o ti taglierò la testa all’istante.” in quel momento tutta la forza abbandonò la strega e dovette obbedire.

“Ti condurrò da tuo fratello,” disse, sperando di avere la meglio su di lui con l’astuzia, “ma lasciami andare. Mi tieni così stretta che non posso camminare.”

“Prendi in giro qualcun altro.” le rispose il ragazzo e la tenne più stretta che mai. Lo condusse in una vasta sala piena di statue di pietra, che una volta erano state uomini, e, indicandone una, disse: “Ecco tuo fratello.”

il ragazzo la guardò e scosse la testa. “Mio fratello non è qui. Portami da lui o sarà peggio per te.” Lei tentò di ingannarlo con altre statue, sebbene non fosse vero, e fu tutto inutile finché raggiunsero l’ultima di tutte le sale e lì vide il fratello che giaceva a terra.

“Quello è mio fratello,” disse il ragazzo, “adesso dammi l’unguento che gli restituirà la vita.”

Assai malvolentieri la vecchia strega aprì una credenza piena di bottiglie e di vasetti, ne tirò giù uno e lo diede al ragazzo. Lui però stava all’erta per i suoi inganni e, esaminatolo attentamente, vide che non aveva il potere di sanare. Ciò accadde molte volte finché alla fine lei vide che non serviva a niente e gli dette ciò che voleva. Quando l’ebbe con certezza, la fece piegare e unse il volto del fratello, badando bene di non lasciar mai andare i capelli della vecchia, e quando il morto aprì gli occhi, il ragazzo estrasse la spada e le tagliò la testa con un solo colpo. Allora il fratello maggiore si alzò e si stirò, poi disse: “Quanto ho dormito! Dove sono?”

“La vecchia strega ha gettato un incantesimo su di te, ma adesso è morta e sei libero. Sveglieremo gli altri cavalieri che teneva sotto incantesimo e poi ce ne andremo.”

E così fecero e, dopo aver diviso tra di loro i gioielli e l’oro trovati nel castello, ognuno prese la propria strada. I due fratelli rimasero insieme, il maggiore tenendo saldamente l’unguento che gli aveva restituito la vita.

Avevano molte cose da raccontarsi a vicenda mentre cavalcavano e alla fine il più giovane esclamò: “Pazzo, hai lasciato una moglie così bella per andare a combattere una strega! Mi ha scambiato per suo marito e io non l’ho negato.”

Quando il fratello maggiore sentì ciò, una grande rabbia gli colmò il cuore e, senza dire una parola, estrasse la spada e uccise il fratello, e il suo corpo rotolò nella polvere. Allora cavalcò finché raggiunse la propria casa in cui la moglie stava ancora seduta, piangendo amaramente.

Quando lo vide, balzò in piedi con un grido e gli si gettò tra le braccia. “Quanto a lungo ti ho atteso! Non devi lasciarmi mai più, mai più!”

Quando il vecchio re sentì la notizia, lo accolse come un figlio e fece approntare un banchetto a cui partecipò tutta la corte. La sera, quando il ragazzo fu solo con la moglie, lei gli disse: “Perché non hai voluto che ti toccassi quando sei tornato e mi hai sempre allontanata quando tentavo di abbracciarti o di baciarti?”

Allora il ragazzo comprese la verità di ciò che gli aveva detto il fratello e sedette a piangere e a torcersi le mani per la malvagia morte che gli aveva inflitto. Improvvisamente balzò in piedi perché si era rammentato dell’unguento che aveva

nascosto tra i vestiti e si precipitò fuori del palazzo verso il luogo in cui giaceva il fratello. Si gettò in ginocchio accanto al suo corpo e, estraendo l’unguento, lo strofinò sul collo dove la ferita era profonda e la pelle si risanò e i tendini si rinsaldarono e il ragazzo morto sedette e si guardò attorno. I due fratelli si abbracciarono e il maggiore chiese perdono per il malvagio colpo; tornarono insieme a palazzo e non si separarono mai più.

Da Fiabe siciliane raccolte da L.Gonzenbach

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)