A long, long way off, in a land where water is very scarce, there lived a man and his wife and several children. One day the wife said to her husband, ‘I am pining to have the liver of a nyamatsane for my dinner. If you love me as much as you say you do, you will go out and hunt for a nyamatsane, and will kill it and get its liver. If not, I shall know that your love is not worth having.’

‘Bake some bread,’ was all her husband answered, ‘then take the crust and put it in this little bag.’

The wife did as she was told, and when she had finished she said to her husband, ‘The bag is all ready and quite full.’

‘Very well,’ said he, ‘and now good-bye; I am going after the nyamatsane.’

But the nyamatsane was not so easy to find as the woman had hoped. The husband walked on and on and on without ever seeing one, and every now and then he felt so hungry that he was obliged to eat one of the crusts of bread out of his bag. At last, when he was ready to drop from fatigue, he found himself on the edge of a great marsh, which bordered on one side the country of the nyamatsanes. But there were no more nyamatsanes here than anywhere else. They had all gone on a hunting expedition, as their larder was empty, and the only person left at home was their grandmother, who was so feeble she never went out of the house. Our friend looked on this as a great piece of luck, and made haste to kill her before the others returned, and to take out her liver, after which he dressed himself in her skin as well as he could. He had scarcely done this when he heard the noise of the nyamatsanes coming back to their grandmother, for they were very fond of her, and never stayed away from her longer than they could help. They rushed clattering into the hut, exclaiming, ‘We smell human flesh! Some man is here,’ and began to look about for him; but they only saw their old grandmother, who answered, in a trembling voice, ‘No, my children, no! What should any man be doing here?’ The nyamatsanes paid no attention to her, and began to open all the cupboards, and peep under all the beds, crying out all the while, ‘A man is here! a man is here!’ but they could find nobody, and at length, tired out with their long day’s hunting, they curled themselves up and fell asleep.

Next morning they woke up quite refreshed, and made ready to start on another expedition; but as they did not feel happy about their grandmother they said to her, ‘Grandmother, won’t you come to-day and feed with us?’ And they led their grandmother outside, and all of them began hungrily to eat pebbles. Our friend pretended to do the same, but in reality he slipped the stones into his pouch, and swallowed the crusts of bread instead. However, as the nyamatsanes did not see this they had no idea that he was not really their grandmother. When they had eaten a great many pebbles they thought they had done enough for that day, and all went home together and curled themselves up to sleep. Next morning when they woke they said, ‘Let us go and amuse ourselves by jumping over the ditch,’ and every time they cleared it with a bound. Then they begged their grandmother to jump over it too, end with a tremendous effort she managed to spring right over to the other side. After this they had no doubt at all of its being their true grandmother, and went off to their hunting, leaving our friend at home in the hut.

As soon as they had gone out of sight our hero made haste to take the liver from the place where he had hid it, threw off the skin of the old nyamatsane, and ran away as hard as he could, only stopping to pick up a very brilliant and polished little stone, which he put in his bag by the side of the liver.

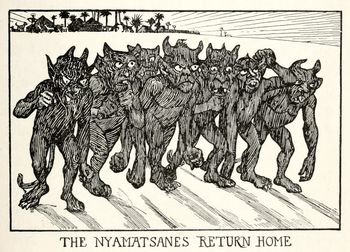

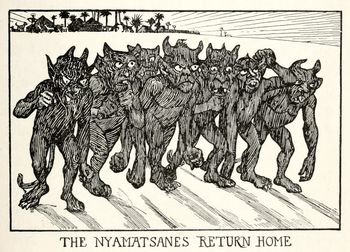

Towards evening the nyamatsanes came back to the hut full of anxiety to know how their grandmother had got on during their absence. The first thing they saw on entering the door was her skin lying on the floor, and then they knew that they had been deceived, and they said to each other, ‘So we were right, after all, and it was human flesh we smelt.’ Then they stooped down to find traces of the man’s footsteps, and when they had got them instantly set out in hot pursuit.

Meanwhile our friend had journeyed many miles, and was beginning to feel quite safe and comfortable, when, happening to look round, he saw in the distance a thick cloud of dust moving rapidly. His heart stood still within him, and he said to himself, ‘I am lost. It is the nyamatsanes, and they will tear me in pieces,’ and indeed the cloud of dust was drawing near with amazing quickness, and the nyamatsanes almost felt as if they were already devouring him. Then as a last hope the man took the little stone that he had picked up out of his bag and flung it on the ground. The moment it touched the soil it became a huge rock, whose steep sides were smooth as glass, and on the top of it our hero hastily seated himself. It was in vain that the nyamatsanes tried to climb up and reach him; they slid down again much faster than they had gone up; and by sunset they were quite worn out, and fell asleep at the foot of the rock.

No sooner had the nyamatsanes tumbled off to sleep than the man stole softly down and fled away as fast as his legs would carry him, and by the time his enemies were awake he was a very long way off. They sprang quickly to their feet and began to sniff the soil round the rock, in order to discover traces of his footsteps, and they galloped after him with terrific speed. The chase continued for several days and nights; several times the nyamatsanes almost reached him, and each time he was saved by his little pebble.

Between his fright and his hurry he was almost dead of exhaustion when he reached his own village, where the nyamatsanes could not follow him, because of their enemies the dogs, which swarmed over all the roads. So they returned home.

Then our friend staggered into his own hut and called to his wife: ‘Ichou! how tired I am! Quick, give me something to drink. Then go and get fuel and light a fire.’

So she did what she was bid, and then her husband took the nyamatsane’s liver from his pouch and said to her, ‘There, I have brought you what you wanted, and now you know that I love you truly.’

And the wife answered, ‘It is well. Now go and take out the children, so that I may remain alone in the hut,’ and as she spoke she lifted down an old stone pot and put on the liver to cook. Her husband watched her for a moment, and then said, ‘Be sure you eat it all yourself. Do not give a scrap to any of the children, but eat every morsel up.’ So the woman took the liver and ate it all herself.

Directly the last mouthful had disappeared she was seized with such violent thirst that she caught up a great pot full of water and drank it at a single draught. Then, having no more in the house, she ran in next door and said, ‘Neighbour, give me, I pray you, something to drink.’ The neighbour gave her a large vessel quite full, and the woman drank it off at a single draught, and held it out for more.

But the neighbour pushed her away, saying, ‘No, I shall have none left for my children.’

So the woman went into another house, and drank all the water she could find; but the more she drank the more thirsty she became. She wandered in this manner through the whole village till she had drunk every water-pot dry. Then she rushed off to the nearest spring, and swallowed that, and when she had finished all the springs and wells about she drank up first the river and then a lake. But by this time she had drunk so much that she could not rise from the ground.

In the evening, when it was time for the animals to have their drink before going to bed, they found the lake quite dry, and they had to make up their minds to be thirsty till the water flowed again and the streams were full. Even then, for some time, the lake was very dirty, and the lion, as king of the beasts, commanded that no one should drink till it was quite clear again.

But the little hare, who was fond of having his own way, and was very thirsty besides, stole quietly off when all the rest were asleep in their dens, and crept down to the margin of the lake and drank his fill. Then he smeared the dirty water all over the rabbit’s face and paws, so that it might look as if it were he who had been disobeying Big Lion’s orders.

The next day, as soon as it was light, Big Lion marched straight for the lake, and all the other beasts followed him. He saw at once that the water had been troubled again, and was very angry.

‘Who has been drinking my water?’ said he; and the little hare gave a jump, and, pointing to the rabbit, he answered, ‘Look there! it must be he! Why, there is mud all over his face and paws!’

The rabbit, frightened out of his wits, tried to deny the fact, exclaiming, ‘Oh, no, indeed I never did;’ but Big Lion would not listen, and commanded them to cane him with a birch rod.

Now the little hare was very much pleased with his cleverness in causing the rabbit to be beaten instead of himself, and went about boasting of it. At last one of the other animals overheard him, and called out, ‘Little hare, little hare! what is that you are saying?’

But the little hare hastily replied, ‘I only asked you to pass me my stick.’

An hour or two later, thinking that no one was near him, he said to himself again, ‘It was really I who drank up the water, but I made them think it was the rabbit.’

But one of the beasts whose ears were longer than the rest caught the words, and went to tell Big Lion about it. "Do you hear what the little hare is saying?’

So Big Lion sent for the little hare, and asked him what he meant by talking like that.

The little hare saw that there was no use trying to hide it, so he answered pertly, ‘It was I who drank the water, but I made them think it was the rabbit.’ Then he turned and ran as fast as he could, with all the other beasts pursuing him.

They were almost up to him when he dashed into a very narrow cleft in the rock, much too small for them to follow; but in his hurry he had left one of his long ears sticking out, which they just managed to seize. But pull as hard as they might they could not drag him out of the hole, and at last they gave it up and left him, with his ear very much torn and scratched.

When the last tail was out of sight the little hare crept cautiously out, and the first person he met was the rabbit. He had plenty of impudence, so he put a bold face on the matter, and said, ‘Well, my good rabbit, you see I have had a beating as well as you.’

But the rabbit was still sore and sulky, and he did not care to talk, so he answered, coldly, ‘You have treated me very badly. It was really you who drank that water, and you accused me of having done it.’

‘Oh, my good rabbit, never mind that! I’ve got such a wonderful secret to tell you! Do you know what to do so as to escape death?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Well, we must begin by digging a hole.’

So they dug a hole, and then the little hare said, ‘The next thing is to make a fire in the hole,’ and they set to work to collect wood, and lit quite a large fire.

When it was burning brightly the little hare said to the rabbit, ‘Rabbit, my friend, throw me into the fire, and when you hear my fur crackling, and I call “Itchi, Itchi,” then be quick and pull me out.’

The rabbit did as he was told, and threw the little hare into the fire; but no sooner did the little hare begin to feel the heat of the flames than he took some green bay leaves he had plucked for the purpose and held them in the middle of the fire, where they crackled and made a great noise. Then he called loudly ‘Itchi, Itchi! Rabbit, my friend, be quick, be quick! Don’t you hear how my skin is crackling?’

And the rabbit came in a great hurry and pulled him out.

Then the little hare said, ‘Now it is your turn!’ and he threw the rabbit in the fire. The moment the rabbit felt the flames he cried out ‘Itchi, Itchi, I am burning; pull me out quick, my friend!’

But the little hare only laughed, and said, ‘No, you may stay there! It is your own fault. Why were you such a fool as to let yourself be thrown in? Didn’t you know that fire burns?’ And in a very few minutes nothing was left of the rabbit but a few bones.

When the fire was quite out the little hare went and picked up one of these bones, and made a flute out of it, and sang this song:

Pii, pii, O flute that I love,

Pii, pii, rabbits are but little boys.

Pii, pii, he would have burned me if he could;

Pii, pii, but I burned him, and he crackled finely.

When he got tired of going through the world singing this the little hare went back to his friends and entered the service of Big Lion. One day he said to his master, ‘Grandfather, shall I show you a splendid way to kill game?’

‘What is it?’ asked Big Lion.

‘We must dig a ditch, and then you must lie in it and pretend to be dead.’

Big Lion did as he was told, and when he had lain down the little hare got up on a wall blew a trumpet and shouted—

Pii, pii, all you animals come and see,

Big Lion is dead, and now peace will be.

Directly they heard this they all came running. The little hare received them and said, ‘Pass on, this way to the lion.’ So they all entered into the Animal Kingdom. Last of all came the monkey with her baby on her back. She approached the ditch, and took a blade of grass and tickled Big Lion’s nose, and his nostrils moved in spite of his efforts to keep them still.

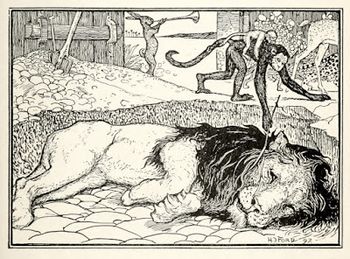

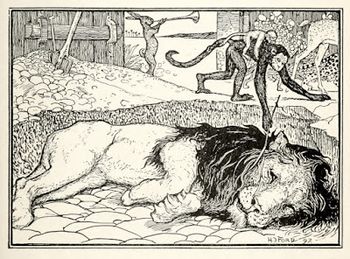

Then the monkey cried, ‘Come, my baby, climb on my back and let us go. What sort of a dead body is it that can still feel when it is tickled?’ And she and her baby went away in a fright. Then the little hare said to the other beasts, ‘Now, shut the gate of the Animal Kingdom.’ And it was shut, and great stones were rolled against it. When everything was tight closed the little hare turned to Big Lion and said ‘Now!’ and Big Lion bounded out of the ditch and tore the other animals in pieces.

But Big Lion kept all the choice bits for himself, and only gave away the little scraps that he did not care about eating; and the little hare grew very angry, and determined to have his revenge. He had long ago found out that Big Lion was very easily taken in; so he laid his plans accordingly. He said to him, as if the idea had just come into his head, ‘Grandfather, let us build a hut,’ and Big Lion consented. And when they had driven the stakes into the ground, and had made the walls of the hut, the little hare told Big Lion to climb upon the top while he stayed inside. When he was ready he called out, ‘Now, grandfather, begin,’ and Big Lion passed his rod through the reeds with which the roofs are always covered in that country. The little hare took it and cried, ‘Now it is my turn to pierce them,’ and as he spoke he passed the rod back through the reeds and gave Big Lion’s tail a sharp poke.

‘What is pricking me so?’ asked Big Lion.

‘Oh, just a little branch sticking out. I am going to break it,’ answered the little hare; but of course he had done it on purpose, as he wanted to fix Big Lion’s tail so firmly to the hut that he would not be able to move. In a little while he gave another prick, and Big Lion called again, ‘What is pricking me so?’

This time the little hare said to himself, ‘He will find out what I am at. I must try some other plan. ‘So he called out, ‘Grandfather, you had better put your tongue here, so that the branches shall not touch you.’ Big Lion did as he was bid, and the little hare tied it tightly to the stakes of the wall. Then he went outside and shouted, ‘Grandfather, you can come down now,’ and Big Lion tried, but he could not move an inch.

Then the little hare began quietly to eat Big Lion’s dinner right before his eyes, and paying no attention at all to his growls of rage. When he had quite done he climbed up on the hut, and, blowing his flute, he chanted ‘Pii, pii, fall rain and hail,’ and directly the sky was full of clouds, the thunder roared, and huge hailstones whitened the roof of the hut. The little hare, who had taken refuge within, called out again, ‘Big Lion, be quick and come down and dine with me.’ But there was no answer, not even a growl, for the hailstones had killed Big Lion.

The little hare enjoyed himself vastly for some time, living comfortably in the hut, with plenty of food to eat and no trouble at all in getting it. But one day a great wind arose, and flung down the Big Lion’s half-dried skin from the roof of the hut. The little hare bounded with terror at the noise, for he thought Big Lion must have come to life again; but on discovering what had happened he set about cleaning the skin, and propped the mouth open with sticks so that he could get through. So, dressed in Big Lion’s skin, the little hare started on his travels.

The first visit he paid was to the hyaenas, who trembled at the sight of him, and whispered to each other, ‘How shall we escape from this terrible beast?’ Meanwhile the little hare did not trouble himself about them, but just asked where the king of the hyaenas lived, and made himself quite at home there. Every morning each hyaena thought to himself, ‘To-day he is certain to eat me;’ but several days went by, and they were all still alive. At length, one evening, the little hare, looking round for something to amuse him, noticed a great pot full of boiling water, so he strolled up to one of the hyaenas and said, ‘Go and get in.’ The hyaena dared not disobey, and in a few minutes was scalded to death. Then the little hare went the round of the village, saying to every hyaena he met, ‘Go and get into the boiling water,’ so that in a little while there was hardly a male left in the village.

One day all the hyaenas that remained alive went out very early into the fields, leaving only one little daughter at home. The little hare, thinking he was all alone, came into the enclosure, and, wishing to feel what it was like to be a hare again, threw off Big Lion’s skin, and began to jump and dance, singing—

I am just the little hare, the little hare, the little hare;

I am just the little hare who killed the great hyaenas.

The little hyaena gazed at him in surprise, saying to herself, ‘What! was it really this tiny beast who put to death all our best people?’ when suddenly a gust of wind rustled the reeds that surrounded the enclosure, and the little hare, in a fright, hastily sprang back into Big Lion’s skin.

When the hyaenas returned to their homes the little hyaena said to her father: ‘Father, our tribe has very nearly been swept away, and all this has been the work of a tiny creature dressed in the lion’s skin.’

But her father answered, ‘Oh, my dear child, you don’t know what you are talking about.’

She replied, ‘Yes, father, it is quite true. I saw it with my own eyes.’

The father did not know what to think, and told one of his friends, who said, ‘To-morrow we had better keep watch ourselves.’

And the next day they hid themselves and waited till the little hare came out of the royal hut. He walked gaily towards the enclosure, threw off, Big Lion’s skin, and sang and danced as before—

I am just the little hare, the little hare, the little hare;

I am just the little hare who killed the great hyaenas.

That night the two hyaenas told all the rest, saying, ‘Do you know that we have allowed ourselves to be trampled on by a wretched creature with nothing of the lion about him but his skin?’

When supper was being cooked that evening, before they all went to bed, the little hare, looking fierce and terrible in Big Lion’s skin, said as usual to one of the hyaenas ‘Go and get into the boiling water.’ But the hyaena never stirred. There was silence for a moment; then a hyaena took a stone, and flung it with all his force against the lion’s skin. The little hare jumped out through the mouth with a single spring, and fled away like lightning, all the hyaenas in full pursuit uttering great cries. As he turned a corner the little hare cut off both his ears, so that they should not know him, and pretended to be working at a grindstone which lay there.

The hyaenas soon came up to him and said, ‘Tell me, friend, have you seen the little hare go by?’

‘No, I have seen no one.’

‘Where can he be?’ said the hyaenas one to another. ‘Of course, this creature is quite different, and not at all like the little hare.’ Then they went on their way, but, finding no traces of the little hare, they returned sadly to their village, saying, ‘To think we should have allowed ourselves to be swept away by a wretched creature like that!’

Contes populaires des Bassoutos. Recueillis et traduits par E. Jacottet. Paris: Leroux, Editeur.

Il leprotto

In una terra molto, molto lontana nella quale l'acqua era molto scarsa, vivevano un uomo, sua moglie e vari bambini. Un giorno la moglie disse al marito: "Mi sto struggendo dal desiderio di avere per cena il fegato di un nyamatsane. (1) Se mi ami tanto quanto dici di amarmi, uscirai e darai la caccia a un nyamatsane, lo ucciderai e prenderai il suo fegato altrimenti, saprò che non vale la pena di avere il tuo amore.”

"Cuoci un po 'di pane" fu tutta la risposta del marito, "poi prendi la crosta e mettila in questa piccola borsa".

La moglie fece come le era stato detto e, quando ebbe finito, disse al marito: "La borsa è pronta e piena".

"Molto bene," disse lui, "e ora addio, vado a cercare il nyamatsane."

Ma il nyamatsane non era così facile da trovare come la donna aveva sperato. Il marito continuò a camminare avanti e indietro senza mai vederne uno, e ogni tanto si sentiva così affamato che era costretto a mangiare una delle croste di pane presa dalla borsa. Alla fine, quando sta quasi per cedere alla fatica, si trovò sul limitare di una grande palude che confinava da un lato il paese dei nyamatsans. Ma qui non c'erano più nyamatsane che altrove. Erano partiti tutti per una spedizione di caccia perché la loro dispensa era vuota e l'unica persona rimasta a casa era la nonna, che era così debole che non usciva mai di casa. Il nostro amico considerò ciò una grande fortuna, e si affrettò a ucciderla prima che gli altri tornassero e a estrarre il fegato, dopo di che si vestì della sua pelle meglio che poté. Lo aveva appena fatto quando sentì il rumore dei nyamatsane che tornavano dalla nonna, perché le erano erano molto affezionati e non stavano mai lontani da lei più a lungo di quanto avrebbero potuto. Si precipitarono rumorosamente nella capanna, esclamando: "Sentiamo odore di carne umana! C'è un uomo qui.”e cominciò a cercarlo, ma videro solo la vecchia nonna, che rispose, con voce tremante: "No, figli miei, no! Che di dovrebbe qui fare qualsiasi uomo? I nyamatsane non la prestarono attenzione e cominciarono ad aprire tutti gli armadi e a sbirciare sotto tutti i letti, gridando per tutto il tempo: "C’è un uomo qui! C’è un uomo qui!” ma non riuscirono a trovare nessuno, e alla fine, stanchi della lunga giornata di caccia, si accoccolarono e si addormentarono.

Il mattino dopo si svegliarono abbastanza riposati e si prepararono a iniziare un'altra spedizione, ma siccome non si sentivano sicuri della nonna, le dissero: "Nonna, oggi non vieni a mangiare con noi?" E portarono fuori la nonna, e tutti cominciarono a mangiare avidamente ciottoli. Il nostro amico fece finta di fare lo stesso, ma in realtà infilava le pietre nella sacca e ingoiava invece le croste di pane. Tuttavia, poiché i nyamatsane non vedevano ciò, non avevano idea che non fosse davvero la loro nonna. Quando ebbero mangiato un gran numero di ciottoli pensavano di aver fatto abbastanza per quel giorno, e tutti andarono a casa insieme e si raggomitolarono per dormire. Il mattino dopo, quando si svegliarono, dissero: "Andiamo a divertirci saltando sul fosso.” e ogni volta lo oltrepassavano con un balzo. Poi pregarono la nonna di saltarci sopra anche lei, con uno sforzo tremendo riuscì a balzare proprio dall'altra parte. Dopo ciò, non ebbero dubbi sulla vera nonna e andarono a caccia, lasciando il nostro amico nella capanna.

Non appena furono spariti dalla vista, il nostro eroe si affrettò a prendere il fegato dal luogo in cui l'aveva nascosto, gettò via la pelle della vecchia nyamatsane e corse via più in fretta che poté, fermandosi solo per raccogliere un piccola pietra molto brillante e levigata, che mise nella borsa accanto al fegato.

Verso sera i nyamatsane tornarono alla capanna assai ansiosi di sapere come si fosse comportata la nonna durante la loro assenza. La prima cosa che videro quando entravano dalla porta fu la sua pelle distesa sul pavimento, e poi seppero di essere stati ingannati e si dissero l'un l'altro: "Quindi avevamo ragione, dopotutto, ed era carne umana che avevamo annusato.” Poi si chinarono per trovare le tracce dei passi dell'uomo e quando l’ebbero fatto, si gettarono immediatamente all'inseguimento.

Nel frattempo il nostro amico aveva percorso molte miglia, e stava cominciando a sentirsi al sicuro e tranquillo quando, guardandosi intorno, vide in lontananza una densa nuvola di polvere muoversi rapidamente. Il cuore gli si fermò e si disse: ‘Sono perso. Sono i nyamatsane, e mi faranno a pezzi.” In effetti la nuvola di polvere si stava avvicinando con sorprendente rapidità e i nyamatsane si sentivano quasi come se lo stessero già divorando. Come ultima risorsa, l'uomo prese la piccola pietra che aveva raccolto dalla borsa e la gettò a terra. Nel momento in cui toccò il terreno divenne un'enorme roccia, i cui lati scoscesi erano lisci come il vetro, e il nostro eroe si sedette rapidamente sulla cima. Invano i nyamatsane cercarono di arrampicarsi e di raggiungerlo; scivolarono molto più velocemente di quanto salissero e al tramonto erano piuttosto stanchi e si addormentarono ai piedi della roccia.

Non appena i nyamatsane si furono addormentati, l'uomo scese piano piano e fuggì alla maggior velocità con cui le gambe lo portassero e quando i nemici si svegliarono, era molto lontano. Si alzarono velocemente in piedi e cominciarono ad annusare il terreno attorno alla roccia, per scoprire le tracce dei suoi passi, e gli corsero dietro con velocità terrificante. L'inseguimento continuò per diversi giorni e notti; parecchie volte i nyamatsane quasi lo raggiunsero e ogni volta fu salvato da uno dei sassolini.

Tra la paura e la fretta era quasi morto di fatica quando raggiunse il suo villaggio, in cui i nyamatsane non potevano seguirlo, a causa dei cani, loro nemici, che brulicavano in tutte le strade. Così essi tornarono a casa.

Poi il nostro amico barcollò nella capanna e chiamò sua moglie: "Ichou! Come sono stanco! Svelta, dammi qualcosa da bere poi vai a prendere la legna e accendi il fuoco. "

La donna fece ciò che le fu chiesto poi suo marito prese il fegato del nyamatsane dalla sacca e le disse: "Ecco, ti ho portato quello che volevi, e ora sai che ti amo davvero".

E la moglie rispose: "Sta bene. Ora vai a prendere i bambini, così che io possa restare da solo nella capanna."e mentre parlava, sollevò una vecchia pentola di pietra e mise il fegato a cucinare. Suo marito la osservò per un momento, poi disse: "Assicurati di mangiarlo tutto da solo. Non darne un brandello a nessuno dei bambini, ma mangia tu ogni boccone.” Così la donna prese il fegato e se lo mangiò tutto da sola.

Appena l'ultimo boccone fu sparito, fu colta da una sete così violenta che raccolse una grande pentola piena d'acqua e la bevve in un solo sorso. Poi, non avendone più in casa, corse alla porta accanto e disse: "Vicina, ti prego, dammi qualcosa da bere". La vicina le diede un grosso vaso quasi pieno e la donna bevve in un solo sorso, e ne chiese di più.

Ma la vicina la spinse via, dicendo: "No, non ne resterà più per i miei figli".

Così la donna entrò in un'altra casa e bevve tutta l'acqua che riuscì a trovare; ma più beveva, più era assetata. Vagò in questo modo per l'intero villaggio fino a quando non ebbe bevuto ogni vaso d'acqua. Poi si precipitò alla sorgente più vicina e la inghiottì e, quando ebbe finito tutte le sorgenti e i pozzi, bevve prima il fiume e poi un lago. Ma ormai aveva bevuto così tanto che non riusciva a sollevarsi da terra.

La sera, quando era tempo che gli animali bevessero prima di andare a dormire, trovarono il lago completamente asciutto e dovettero rassegnarsi ad avere sete finché l'acqua non scorse di nuovo e i ruscelli furono colmi. Persino allora, per qualche tempo, il lago fu molto sporco e il leone, quale re degli animali, ordinò che nessuno bevesse finché non fosse di nuovo abbastanza limpido.

Ma il leprotto, che preferiva fare a modo proprio e aveva anche molta sete, se ne andò silenziosamente quando tutti gli altri dormivano nelle loro tane, e sgusciò fino al bordo del lago e bevve a sazietà. Poi sparse l'acqua sporca sul muso e sulle zampe del coniglio, in modo che sembrasse che fosse lui a disobbedire agli ordini del Grande Leone.

Il giorno seguente, appena vi fu luce, il Grande Leone si diresse verso il lago e tutti gli altri animali lo seguirono. Vide subito che l'acqua era stata di nuovo intorbidita e si arrabbiò molto.

"Chi ha bevuto la mia acqua?" disse, e il leprotto fece un salto e rispose, indicando il coniglio: "Guarda lì! Deve essere stato lui!C'è fango su tutto il muso e sulle zampe!

Il coniglio, spaventato dalla sua presenza di spirito cercò di negare il fatto, esclamando: "Oh, no, davvero non l'ho mai fatto" ma il Grande Leone non volle ascoltarlo e ordinò loro di fustigarlo con una verga di betulla.

Ora il leprotto era molto contento che la propria astuzia avesse permesso che il coniglio fosse picchiato al posto suo, e andava vantandosene. Alla fine uno degli altri animali lo sentì e disse: "Leprotto, leprotto! Che cosa stai dicendo? '

Ma il leprotto rispose frettolosamente: "Ti ho solo chiesto di passarmi il bastone".

Un'ora o due dopo, pensando che nessuno gli fosse vicino, si disse di nuovo: "Sono stato davvero io a bere l'acqua, ma ho fatto in modo pensassero che fosse il coniglio".

Ma una delle bestie, le cui orecchie erano più lunghe di quelle degli altri, captò le parole e andò a dirlo al Grande Leone. “Senti cosa sta dicendo il leprotto?

Così il Grande Leone mandò a chiamare il leprotto e gli chiese cosa intendesse dire, parlando in quel modo.

Il leprotto vide che non serviva a nulla cercare di nasconderlo, così rispose in modo educato: "Sono stato io a bere l'acqua, ma ho fatto in modo pensassero che fosse stato il coniglio". Poi si voltò e corse più veloce che poté, con tutte le altre bestie che lo inseguivano.

L’avevano quasi raggiunto quando si infilò in una fessura molto stretta nella roccia, troppo piccola per essi lo seguissero, ma nella fretta lasciò sporgere una delle sue lunghe orecchie per cui riuscirono a catturarlo. Per quanto tirassero con tutte le loro forze,,non riuscirono a trascinare fuori dal buco e alla fine rinunciarono e lo lasciarono lì, con l'orecchio tutto strappato e graffiato.

Quando l'ultima coda scomparve alla sua vista, il leprotto uscì cautamente e la prima creatura che incontrò fu il coniglio. Era molto impudente, quindi assunse un’aria ardita riguardo la faccenda e disse: "Bene, mio ??buon coniglio, vedi che sono stato picchiato come te".

Ma il coniglio era ancora dolorante e scontroso, e non gli importava niente di parlare, così rispose freddamente: "Mi hai trattato molto male. Sei stato davvero tu a bere quell'acqua e hai accusato me di averlo fatto. "

"Oh, mio ??buon coniglio, non importa! Ho un segreto così meraviglioso da dirti! Sai cosa fare per sfuggire alla morte?

"No, non lo so."

"Ebbene, dobbiamo iniziare scavando un buco."

Così scavarono un buco e poi il leprotto disse: "La prossima cosa è accendere un fuoco nel buco", e si misero al lavoro per raccogliere legna e accesero un bel fuoco.

Quando stava bruciando vivamente, il leprotto disse al coniglio: "Coniglio, amico mio, gettami nel fuoco, e quando sentirai scoppiettare la mia pelliccia e chiamare ‘Itchi, Itchi’ allora sbrigati a tirami fuori. '

Il coniglio fece come gli era stato detto e gettò il leprotto nel fuoco; appena il leprotto cominciò a sentire il calore delle fiamme, prese delle foglie verdi di alloro che aveva raccolto per lo scopo e le tenne nel mezzo del fuoco, dove crepitarono e fecero un gran rumore. Poi chiamò ad alta voce "Itchi, Itchi! Coniglio, amico mio, svelto, svelto! Non senti come sta crepitando la mia pelle?

E il coniglio arrivò in gran fretta e lo tirò fuori.

Poi il leprotto disse: "Adesso tocca a te!" e gettò il coniglio nel fuoco. Nel momento in cui il coniglio sentì le fiamme gridò "Itchi, Itchi, sto bruciando; svelto, tirami fuori, amico mio!

Ma il leprotto si limitò a ridere e disse: "No, puoi restare lì! È colpa tua. Perché sei stato così sciocco da lasciartici gettare? Non sapevi che il fuoco brucia? E in pochissimi minuti del coniglio non rimase altro che poche ossa.

Quando il fuoco fu quasi spento, il leprotto andò a prendere una di quelle ossa, ne fece un flauto e cantò questa canzone:

Pii, pii, O flauto che amo,

Pii, pii, i conigli non sono che ragazzini.

Pii, pii, mi avrebbe fatto bruciare se avesse potuto;

Pii, pii, ma l'ho bruciato io, e ha scoppiettato ben bene.

Quando fu stanco di andare per il mondo cantando così, il leprotto tornò dai suoi amici ed entrò al servizio del Grande leone. Un giorno disse al suo padrone: "Nonno, ti posso mostrare uno splendido modo per uccidere?"

'Qual è?” chiese il Grande Leone.

"Dobbiamo scavare una fossa e poi ti ci devi sdraiare e fingere di essere morto."

Il Grande Leone fece come gli era stato detto e, quando si fu sdraiato, il leprotto salì su un muro, suonò una tromba e gridò:

Pii, pii, tutti voi animali venite a vedere,

il Grande Leone è morto, e ora la pace potremo avere.

Appena lo sentirono, vennero tutti correndo. Il leprotto li accolse e disse: "Andate avanti, da questa parte per il leone". Così entrarono tutti nel Regno degli Animali. Ultima fra tutti arrivò la scimmia con il suo cucciolo sulla schiena. Si avvicinò al fossato, prese un filo d'erba e fece il solletico al naso del Grande Leone e le sue narici si mossero nonostante gli sforzi per tenerle ferme.

Poi la scimmia gridò: "Vieni, piccolo mio, sali sulla mia schiena e andiamo via. Che razza di cadavere può ancora sentire quando viene solleticato?” E lei e il suo piccolo se ne andarono via spaventati. Poi il leprotto disse alle altre bestie: "Ora, chiudete il cancello del Regno degli Animali". Fu chiuso e grandi pietre vennero fatte rotolare contro di esso. Quando tutto fu ben serrato, il leprotto si rivolse al Grande Leone e disse "Adesso!” e il Grande Leone balzò fuori dalla fossa e fece a pezzi gli altri animali

Il Grande Leone teneva per sé tutti i pezzi selezionati, e dava via solo i piccoli avanzi che non gli importava di mangiare; il leprotto si arrabbiò molto e decise di vendicarsi. Aveva scoperto da tempo che il Grande Leone poteva essere facilmente catturato così ordì i propri piani di conseguenza. Come se l'idea gli fosse appena venuta in mente, gli disse: "Nonno, costruiamo una capanna" e il Grande Leone acconsentì. E quando ebbero messo le palizzate nel terreno e alzati i muri della capanna, il leprotto disse al Grande leone di arrampicarsi sulla sommità mentre lui rimaneva dentro. Quando fu pronto, gridò: "Adesso, nonno, comincia," e il Grande leone passò il suo bastone tra le canne con le quali i tetti sono sempre coperti in quel paese. La piccola lepre lo prese e gridò: “Adesso è il mio turno di passarlo.” e, mentre parlava, passò il bastone attraverso le canne e diede un brusco colpo alla coda del Grande Leone.

"Perché mi sta punzecchiando così?" chiese il Grande Leone.

"Oh, è solo un rametto sporgente. Ho intenzione di romperlo.” rispose il leprotto, ma naturalmente lo aveva fatto apposta perché voleva fissare la coda del Grande Leone così saldamente alla capanna che non sarebbe stato in grado di muoversi. Poco dopo gli diede un'altra puntura, e il Grande Leone lo chiamò di nuovo, “Perché mi stai punzecchiando così?”

Questa volta il leprotto si disse: ‘Scoprirà che cosa sto facendo. Devo ideare qualche altro piano.’ Così gridò: " Nonno, faresti meglio a mettere la lingua qui, in modo che i rami non ti tocchino." Il Grande Leone fece come gli era stato detto e il leprotto lo legò saldamente ai paletti del muro. Poi uscì e gridò: "Nonno, puoi venire giù adesso" e il Grande Leone ci provò, ma non riuscì a muoversi di un pollice.

Poi il leprotto iniziò tranquillamente a mangiare la cena del Grande Leone proprio davanti ai suoi occhi, senza prestare alcuna attenzione ai suoi ringhi di rabbia. Quando ebbe finito, salì sulla capanna e, soffiando il suo flauto, cantò: "Pii, pii, cadete pioggia e grandine", e subito il cielo si riempì di nuvole, il tuono ruggì, e grossi chicchi di grandine imbiancarono il tetto della capanna. Il leprotto, che si era rifugiata dentro, chiamò di nuovo: "Grande Leone, brigati a scendere e vieni a cena con me". Ma non ci fu risposta, nemmeno un ringhio, perché i chicchi di grandine avevano ucciso il Grande Leone.

La piccola lepre si divertì moltissimo per un po' di tempo, vivendo comodamente nella capanna, con un sacco di cibo da mangiare e senza problemi nel procurarselo. Ma un giorno si alzò un grande vento e gettò giù dal tetto della capanna la pelle mezzo secca del Grande Leone. Il leprotto fu colto dal terrore al rumore, perché pensava che il Grande Leone fosse tornato di nuovo in vita; ma quando scoprì ciò che era accaduto, si mise a pulire la pelle e tenne la bocca aperta con bastoncini in modo che ci potesse passare attraverso. Così, vestito con la pelle del Grande Leone, il leprotto iniziò a viaggiare.

La prima visita che fece fu alle le iene, che tremarono alla sua vista e si sussurrarono l'un l'altra: "Come potremo sfuggire a questa terribile bestia?" Nel frattempo il leprotto non si preoccupò affatto di loro, ma chiese solo dove vivesse il re delle iene, e si stabilì lì. Ogni mattina ogni iena pensava tra sé: "Oggi di sicuro mi mangia" ma passarono diversi giorni ed erano ancora tutte vive. Infine una sera il leprotto, cercando qualcosa per divertirsi, notò una grande pentola piena d'acqua bollente, così si avvicinò a una delle iene e disse: "Vai e entra". La iena non osò disobbedire e in pochi minuti fu ustionata a morte. Poi il leprotto fece il giro del villaggio, dicendo a ogni iena che incontrava “Vai dentro l’acqua bollente.” così che in breve rimase a malapena un maschio nel villaggio.

Un giorno tutte le iene che erano rimaste vive andarono molto presto nei campi, lasciando solo una piccola figlia a casa. Il leprotto, pensando di essere solo, entrò nel recinto e, desiderando provare di nuovo come fosse essere una lepre, gettò via la pelle del Grande Leone, e cominciò a saltare e ballare, cantando:

Sono solo il leprotto, il leprotto, il leprotto;

Sono solo il leprotto che ha ucciso le grandi iene.

La piccola iena lo guardò sorpresa, dicendosi: ‘Ma come! è stato davvero questo piccolo animale a mettere a morte tutti migliori di noi?' quando all'improvviso una folata di vento fece frusciare le canne che circondavano il recinto e il leprotto, spaventato, tornò in fretta nella pelle del Grande Leone.

Quando le iene tornarono a casa, la piccola iena disse al padre: "Padre, la nostra tribù è stata quasi spazzata via e tutto ciò è stato opera di una piccola creatura vestita con la pelle del leone".

Ma suo padre rispose: "Oh, mia cara bambina, non sai di cosa stai parlando".

Lei rispose: "Sì, padre, è proprio vero. L'ho visto con i miei occhi.”

Il padre non sapeva che cosa pensare e lo raccontò a uno dei suoi amici, che disse: "Domani farò meglio a dare un’occhiata noi stessi".

E il giorno seguente si nascosero e attesero che il leprotto uscisse dalla capanna reale. Camminò allegramente verso il recinto, gettò via la pelle del Grande Leone, e cantò e ballò come la volta precedente:

Sono solo il leprotto, il leprotto, il leprotto;

Sono solo il leprotto che ha ucciso le grandi iene.

Quella notte le due iene raccontarono tutto, dicendo: "Sapete che abbiamo permesso di essere schiacciati da una miserabile creatura che del leone non ha altro se non la pelle?"

Quella sera, mentre stava cuocendo la cena, prima che tutti andassero a letto, il leprotto, che sembrava feroce e terribile nella pelle del Grande Leone, disse come al solito a una delle iene: "Vai a buttarti nell'acqua bollente". Ma la iena non si mosse . Ci fu silenzio per un momento poi un iena prese una pietra e la scagliò con tutta la sua forza contro la pelle del leone. Il leprotto saltò fuori dalla bocca con un solo balzo e fuggì via come un fulmine, tutte le iene insieme lo inseguirono emettendo grandi grida. Mentre girava un angolo, il leprotto si tagliò le orecchie, in modo che non lo conoscessero, e finse di lavorare a una macina che si trovava lì.

Le iene ben presto gli si avvicinarono e dissero: "Dimmi, amico, hai visto passare di qui il leprotto?"

"No, non ho visto nessuno."

"Dove può essere?" si dissero le iene l'una l'altra. "Certo, questa creatura è molto diversa e non somiglia proprio al leprotto." Poi se ne andarono, ma, non trovando alcuna traccia del leprotto, tornarono tristemente al loro villaggio, dicendo: ' E pensare che abbiamo permesso di essere spazzati via da una simile miserabile creatura!'

(1) Creatura del folclore dei Basotho, la nazione è l’attuale Leshoto, dall’aspetto simile a quello di un grosso babbuino.

Racconti popolari dei Basotho raccolti e tradotti da E. Jacottet, Parigi, e pubblicati da Leroux.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)