The History of Whittington

(MP3-17' 09'')

Dick Whittington was a very little boy when his father and mother died; so little, indeed, that he never knew them, nor the place where he was born. He strolled about the country as ragged as a colt, till he met with a wagoner who was going to London, and who gave him leave to walk all the way by the side of his wagon without paying anything for his passage. This pleased little Whittington very much, as he wanted to see London sadly, for he had heard that the streets were paved with gold, and he was willing to get a bushel of it; but how great was his disappointment, poor boy! when he saw the streets covered with dirt instead of gold, and found himself in a strange place, without a friend, without food, and without money.

Though the wagoner was so charitable as to let him walk up by the side of the wagon for nothing, he took care not to know him when he came to town, and the poor boy was, in a little time, so cold and hungry that he wished himself in a good kitchen and by a warm fire in the country.

In his distress he asked charity of several people, and one of them bid him "Go to work for an idle rogue." "That I will," said Whittington, "with all my heart; I will work for you if you will let me."

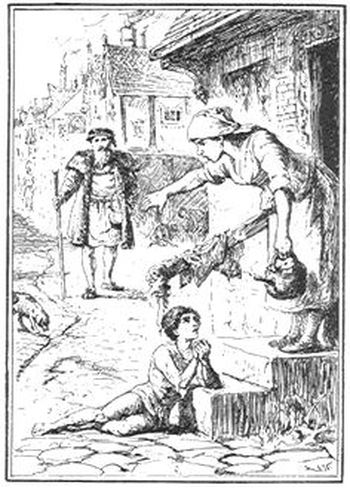

The man, who thought this savored of wit and impertinence (though the poor lad intended only to show his readiness to work), gave him a blow with a stick which broke his head so that the blood ran down. In this situation, and fainting for want of food, he laid himself down at the door of one Mr. Fitzwarren, a merchant, where the cook saw him, and, being an ill-natured hussy, ordered him to go about his business or she would scald him. At this time Mr. Fitzwarren came from the Exchange, and began also to scold at the poor boy, bidding him to go to work.

Whittington answered that he should be glad to work if anybody would employ him, and that he should be able if he could get some victuals to eat, for he had had nothing for three days, and he was a poor country boy, and knew nobody, and nobody would employ him.

He then endeavored to get up, but he was so very weak that he fell down again, which excited so much compassion in the merchant that he ordered the servants to take him in and give him some meat and drink, and let him help the cook to do any dirty work that she had to set him about. People are too apt to reproach those who beg with being idle, but give themselves no concern to put them in the way of getting business to do, or considering whether they are able to do it, which is not charity.

But we return to Whittington, who could have lived happy in this worthy family had he not been bumped about by the cross cook, who must be always roasting and basting, or when the spit was idle employed her hands upon poor Whittington! At last Miss Alice, his master's daughter, was informed of it, and then she took compassion on the poor boy, and made the servants treat him kindly.

Besides the crossness of the cook, Whittington had another difficulty to get over before he could be happy. He had, by order of his master, a flock-bed placed for him in a garret, where there was a number of rats and mice that often ran over the poor boy's nose and disturbed him in his sleep. After some time, however, a gentleman who came to his master's house gave Whittington a penny for brushing his shoes. This he put into his pocket, being determined to lay it out to the best advantage; and the next day, seeing a woman in the street with a cat under her arm, he ran up to know the price of it. The woman (as the cat was a good mouser) asked a deal of money for it, but on Whittington's telling her he had but a penny in the world, and that he wanted a cat sadly, she let him have it.

This cat Whittington concealed in the garret, for fear she should be beat about by his mortal enemy the cook, and here she soon killed or frightened away the rats and mice, so that the poor boy could now sleep as sound as a top.

Soon after this the merchant, who had a ship ready to sail, called for his servants, as his custom was, in order that each of them might venture something to try their luck; and whatever they sent was to pay neither freight nor custom, for he thought justly that God Almighty would bless him the more for his readiness to let the poor partake of his fortune.

All the servants appeared but poor Whittington, who, having neither money nor goods, could not think of sending anything to try his luck; but his good friend Miss Alice, thinking his poverty kept him away, ordered him to be called.

She then offered to lay down something for him, but the merchant told his daughter that would not do, it must be something of his own. Upon which poor Whittington said he had nothing but a cat which he bought for a penny that was given him. "Fetch thy cat, boy," said the merchant, "and send her." Whittington brought poor puss and delivered her to the captain, with tears in his eyes, for he said he should now be disturbed by the rats and mice as much as ever. All the company laughed at the adventure but Miss Alice, who pitied the poor boy, and gave him something to buy another cat.

While puss was beating the billows at sea, poor Whittington was severely beaten at home by his tyrannical mistress the cook, who used him so cruelly, and made such game of him for sending his cat to sea, that at last the poor boy determined to run away from his place, and having packed up the few things he had, he set out very early in the morning on All-Hallows day. He traveled as far as Holloway, and there sat down on a stone to consider what course he should take; but while he was thus ruminating, Bow bells, of which there were only six, began to ring; and he thought their sounds addressed him in this manner:

"Turn again, Whittington,

Thrice Lord Mayor of London."

"Lord Mayor of London!" said he to himself, "what would not one endure to be Lord Mayor of London, and ride in such a fine coach? Well, I'll go back again, and bear all the pummelling and ill-usage of Cicely rather than miss the opportunity of being Lord Mayor!" So home he went, and happily got into the house and about his business before Mrs. Cicely made her appearance.

We must now follow Miss Puss to the coast of Africa. How perilous are voyages at sea, how uncertain the winds and the waves, and how many accidents attend a naval life!

The ship that had the cat on board was long beaten at sea, and at last, by contrary winds, driven on a part of the coast of Barbary which was inhabited by Moors unknown to the English. These people received our countrymen with civility, and therefore the captain, in order to trade with them, showed them the patterns of the goods he had on board, and sent some of them to the King of the country, who was so well pleased that he sent for the captain and the factor to come to his palace, which was about a mile from the sea. Here they were placed, according to the custom of the country, on rich carpets, flowered with gold and silver; and the King and Queen being seated at the upper end of the room, dinner was brought in, which consisted of many dishes; but no sooner were the dishes put down but an amazing number of rats and mice came from all quarters and devoured all the meat in an instant.

The factor, in surprise, turned round to the nobles and asked if these vermin were not offensive. "Oh! yes," said they, "very offensive; and the King would give half his treasure to be freed of them, for they not only destroy his dinner, as you see, but they assault him in his chamber, and even in bed, so that he is obliged to be watched while he is sleeping, for fear of them."

The factor jumped for joy; he remembered poor Whittington and his cat, and told the King he had a creature on board the ship that would despatch all these vermin immediately. The King's heart heaved so high at the joy which this news gave him that his turban dropped off his head. "Bring this creature to me," said he; "vermin are dreadful in a court, and if she will perform what you say I will load your ship with gold and jewels in exchange for her." The factor, who knew his business, took this opportunity to set forth the merits of Miss Puss. He told his Majesty that it would be inconvenient to part with her, as, when she was gone, the rats and mice might destroy the goods in the ship—but to oblige his Majesty he would fetch her. "Run, run," said the Queen; "I am impatient to see the dear creature."

Away flew the factor, while another dinner was providing, and returned with the cat just as the rats and mice were devouring that also. He immediately put down Miss Puss, who killed a great number of them.

The King rejoiced greatly to see his old enemies destroyed by so small a creature, and the Queen was highly pleased, and desired the cat might be brought near that she might look at her. Upon which the factor called "Pussy, pussy, pussy!" and she came to him. He then presented her to the Queen, who started back, and was afraid to touch a creature who had made such havoc among the rats and mice; however, when the factor stroked the cat and called "Pussy, pussy!" the Queen also touched her and cried "Putty, putty!" for she had not learned English.

He then put her down on the Queen's lap, where she, purring, played with her Majesty's hand, and then sang herself to sleep.

The King, having seen the exploits of Miss Puss, and being informed that her kittens would stock the whole country, bargained with the captain and factor for the whole ship's cargo, and then gave them ten times as much for the cat as all the rest amounted to. On which, taking leave of their Majesties and other great personages at court, they sailed with a fair wind for England, whither we must now attend them.

The morn had scarcely dawned when Mr. Fitzwarren arose to count over the cash and settle the business for that day. He had just entered the counting-house, and seated himself at the desk, when somebody came, tap, tap, at the door. "Who's there?" said Mr. Fitzwarren. "A friend," answered the other. "What friend can come at this unseasonable time?" "A real friend is never unseasonable," answered the other. "I come to bring you good news of your ship Unicorn." The merchant bustled up in such a hurry that he forgot his gout; instantly opened the door, and who should be seen waiting but the captain and factor, with a cabinet of jewels, and a bill of lading, for which the merchant lifted up his eyes and thanked heaven for sending him such a prosperous voyage. Then they told him the adventures of the cat, and showed him the cabinet of jewels which they had brought for Mr. Whittington. Upon which he cried out with great earnestness, but not in the most poetical manner:

"Go, send him in, and tell him of his fame,

And call him Mr. Whittington by name."

It is not our business to animadvert upon these lines; we are not critics, but historians. It is sufficient for us that they are the words of Mr. Fitzwarren; and though it is beside our purpose, and perhaps not in our power to prove him a good poet, we shall soon convince the reader that he was a good man, which was a much better character; for when some who were present told him that this treasure was too much for such a poor boy as Whittington, he said: "God forbid that I should deprive him of a penny; it is his own, and he shall have it to a farthing." He then ordered Mr. Whittington in, who was at this time cleaning the kitchen and would have excused himself from going into the counting-house, saying the room was swept and his shoes were dirty and full of hob-nails. The merchant, however, made him come in, and ordered a chair to be set for him. Upon which, thinking they intended to make sport of him, as had been too often the case in the kitchen, he besought his master not to mock a poor simple fellow, who intended them no harm, but let him go about his business. The merchant, taking him by the hand, said: "Indeed, Mr. Whittington, I am in earnest with you, and sent for you to congratulate you on your great success. Your cat has procured you more money than I am worth in the world, and may you long enjoy it and be happy!"

At length, being shown the treasure, and convinced by them that all of it belonged to him, he fell upon his knees and thanked the Almighty for his providential care of such a poor and miserable creature. He then laid all the treasure at his master's feet, who refused to take any part of it, but told him he heartily rejoiced at his prosperity, and hoped the wealth he had acquired would be a comfort to him, and would make him happy. He then applied to his mistress, and to his good friend Miss Alice, who refused to take any part of the money, but told him she heartily rejoiced at his good success, and wished him all imaginable felicity. He then gratified the captain, factor, and the ship's crew for the care they had taken of his cargo. He likewise distributed presents to all the servants in the house, not forgetting even his old enemy the cook, though she little deserved it.

After this Mr. Fitzwarren advised Mr. Whittington to send for the necessary people and dress himself like a gentleman, and made him the offer of his house to live in till he could provide himself with a better.

Now it came to pass when Mr. Whittington's face was washed, his hair curled, and he dressed in a rich suit of clothes, that he turned out a genteel young fellow; and, as wealth contributes much to give a man confidence, he in a little time dropped that sheepish behavior which was principally occasioned by a depression of spirits, and soon grew a sprightly and good companion, insomuch that Miss Alice, who had formerly pitied him, now fell in love with him.

When her father perceived they had this good liking for each other he proposed a match between them, to which both parties cheerfully consented, and the Lord Mayor, Court of Aldermen, Sheriffs, the Company of Stationers, the Royal Academy of Arts, and a number of eminent merchants attended the ceremony, and were elegantly treated at an entertainment made for that purpose.

History further relates that they lived very happy, had several children, and died at a good old age. Mr. Whittington served as Sheriff of London and was three times Lord Mayor. In the last year of his mayoralty he entertained King Henry V and his Queen, after his conquest of France, upon which occasion the King, in consideration of Whittington's merit, said: "Never had prince such a subject"; which being told to Whittington at the table, he replied: "Never had subject such a king." His Majesty, out of respect to his good character, conferred the honor of knighthood on him soon after.

Sir Richard many years before his death constantly fed a great number of poor citizens, built a church and a college to it, with a yearly allowance for poor scholars, and near it erected a hospital.

He also built Newgate for criminals, and gave liberally to St. Bartholomew's Hospital and other public charities.

Unknown

La storia di Whittington

Dick Whittington era un bambino molto piccolo quando suo padre e sua madre morirono; davvero così piccolo che non sapeva nulla di loro, né in quale luogo fosse nato. Andò in giro per il paese, cencioso come un mendicante, finché incontrò un carrettiere che stava andando a Londra e che gli permise di fare la strada accanto al suo carro senza pagare nulla per il passaggio. Ciò piacque molto al piccolo Whittington, in quanto voleva tanto vedere Londra, perché aveva sentito che le sue strade erano lastricate d’oro e voleva prenderne uno staio; ma quale fu la sua delusione, povero bambino, quando vide le strade coperte di rifiuti anziché d’oro e si ritrovò in uno strano posto, senza un amico, senza cibo e senza denaro.

Sebbene il carrettiere fosse stato così caritatevole da lasciarlo camminare gratis accanto al carro, non si curò di sapere dove andasse in città e in poco tempo il povero bambino si ritrovò così infreddolito e affamato da desiderare di trovarsi in una bella cucina davanti a un caldo fuoco.

In difficoltà chiese l’elemosina a varie persone e una di esse gli disse: “Vai a lavorare per un pigro briccone.” “Lo farò,” disse Whittington, “con tutto il cuore; lavorerò per voi, se vorrete permettermelo.”

L’uomo, che pensò fosse una battuta di spirito e impertinenza, (sebbene il povero ragazzo avesse inteso solo mostrare la propria attitudine al lavoro), gli diede un colpo tale con un bastone che gli ferì la testa tanto da farlo sanguinare. In questo stato, e farneticando di volere del cibo, si lasciò cadere davanti alla porta di un certo messer Fitzwarren, un mercante, e lì la cuoca lo e vide e, essendo una ragazzaccia cattiva, gli ordinò di andarsene per i fatti suoi o lo avrebbe scottato. In quel momento messer Fitzwarren tornava dalla Borsa e cominciò a sgridare il povero ragazzo, ordinandogli di andare a lavorare.

Whittington rispose che sarebbe stato lieto di andare a lavorare se qualcuno lo avesse assunto, e che ne sarebbe stato in grado se avesse potuto avere qualcosa da mangiare perché non ne aveva avuto da tre giorni, era un povero ragazzo di campagna che non conosceva nessuno e che nessuno voleva assumere.

Allora si sforzò di alzarsi, ma era così debole che cadde di nuovo, il che mosse a compassione il mercante, che ordinò ai servi di prenderlo e di dargli un po’ di carne e una bevanda e lasciò che aiutasse la cuoca in qualsiasi sudicio lavoro lei volesse utilizzarlo. Le persone tendono troppo a rimproverare i mendicanti, ma non si preoccupano di metterli in condizione di fare qualcosa o di considerare ciò che sarebbero in grado di fare, il che non è elemosina.

Ma torniamo a Whittington, che sarebbe vissuto felicemente in questa degna famiglia se non fosse stato picchiato dalla rabbiosa cuoca, che doveva sempre condire e arrostire la carne, ma quando lo spiedo era vuoto, impiegava le mani sul povero Whittington! Alla fine, madamigella Alice, la figlia del padrone, fu informata di ciò e allora ebbe compassione del povero ragazzino e fece in modo che i servi lo trattassero gentilmente.

Oltre ai maltrattamenti della cuoca, Whittington aveva un’altra difficoltà che gli impediva di essere felice. Per ordine del padrone, il suo pagliericcio era stato collocato in una soffitta in cui c’era un gran numero di ratti e di topi che scorrazzavano sul naso del povero ragazzo e disturbavano il suo sonno. Dopo un po’ di tempo, in ogni modo, un gentiluomo che era venuto a casa del suo padrone diede a Whittington un penny per lucidargli le scarpe. Lui se lo mise in tasca, deciso a trarne il miglior beneficio; il giorno seguente, vedendo per strada una donna con una gatta sotto il braccio, corse a chiedergliene il prezzo. La donna (siccome la gatta era una buona cacciatrice di topi) chiese un bel po’ di denaro, ma siccome Whittington le disse di possedere un solo un penny, e purtroppo aveva bisogno di un gatto, gliela lasciò prendere.

Whittington nascose la gatta in soffitta, per paura che la cuoca sua nemica potesse picchiarla, e lì ben presto la gatta uccise o spaventò ratti e topi così che il povero ragazzo poté finalmente dormire sodo.

Dopo un po’ di tempo questo mercante, che aveva una nave pronta a salpare, chiamò i servi, come era sua abitudine, affinché ciascuno di loro potesse tentare la sorte in cerca di fortuna; e chiunque partisse, non pagava né merci né imbarco perché egli pensava che Dio Onnipotente lo avrebbe benedetto per la sua disponibilità a lasciare che quei poveracci condividessero la sua fortuna.

Vennero tutti i servi, ma il povero Whittington, non avendo né denaro né beni, non pensò di poter fare nulla per tentare la sorte, ma la sua buona amica Alice, pensando che la sua miseria lo tenesse a distanza, ordinò che fosse chiamato.

Allora offrì di dare qualcosa per lui, ma il mercante disse alla figlia che non poteva perchè doveva trattarsi di qualcosa di suo. Al che il povero Whittington disse di non avere altro che una gatta che aveva acquistato per un penny che gli era stato dato. “Il mercante disse: “Prendi la gatta e vendila.” Whittington prese la povera gatta e la consegnò al capitano con le lacrime agli occhi perché disse che sarebbe stato disturbato più che mai da ratti e topi. Tutta la combriccola rise di ciò, ma madamigella Alice, che aveva compassione del povero ragazzo, gli diede qualcosa per comprare un altro gatto.

Mentre la gatta era sbattuta dai cavalloni del mare, il povero Whittington era battuto duramente dalla sua tirannica padrona, la cuoca, la quale lo trattava così crudelmente e gliene faceva tante per aver mandato per mare la sua gatta che infine il povero ragazzo decise di scappare da quel posto e, impacchettate le poche cose che possedeva, se ne andò di mattina presto il giorno di Ognissanti. Andò lontano da Holloway e se dette su una pietra a considerare che linea di condotta avrebbe seguito; ma mentre era lì a rimuginare, cominciarono a suonare le campane, delle quali ce n’erano solo sei, e pensò che la loro musica si rivolgesse a lui in questo modo:

”Torna indietro, Whittington

Tre volte Sindaco di Londra.”

’Sindaco di Londra!’ disse tra sé, ‘chi potrebbe resistere all’idea di diventare Sindaco di Londra e viaggiare in una così bella carrozza? Ebbene, tornerò indietro e sopporterò tutte le batoste e i maltrattamenti di Cecilia pur di non perdere l’opportunità di diventare Sindaco!’. Così tornò a casa e rientrò felice nell’abitazione e alle proprie faccende prima che comparisse Cecilia.

Adesso però dobbiamo seguire la gattina sulle coste dell’Africa. Quanto è pericoloso il viaggio per mare, quanto sono incerti i venti e le onde e quanti incidenti capitano nella vita a bordo di una nave!

La nave con a bordo la gatta fu a lungo battuta dai marosi e alla fine, con i venti contrari, fu condotta su una parte della costa della Barberia che era abitata da Mori sconosciuti agli Inglesi. Queste genti ricevettero i nostri cittadini con educazione e quindi il capitano, allo scopo di fare affari con loro, esibì tutti i generi di beni che aveva a bordo e ne mandò un po’ al Re del paese, il quale ne fu così compiaciuto che mandò a chiamare il capitano e l’amministratore perché venissero nel suo palazzo, che si trovava ad alcune miglia dal mare. Secondo le usanze del paese lì furono fatti accomodare su ricchi tappeti intessuti d’oro e d’argento; il Re e la Regina erano seduti e i piatti erano stati appena posati che un incredibile numero di ratti e di topi giunsero da ogni parte e divorarono in un istante tutta la carne.

Sorpreso, l’amministratore si rivolse ai nobili e chiese se questi animali non fossero sgradevoli. Risposero: “Sì, sono molto sgradevoli e il Re darebbe metà del suo tesoro per esserne liberato perché essi non solo gli devastano i pasti, come avete visto, ma lo assalgono nella sua stanza, persino a letto, così è costretto a farsi sorvegliare mentre dorme, per paura di essi.”

L’amministratore fece un salto di gioia; si era rammentato del povero Whittington e della sua gatta e disse al Re di avere a bordo della nave una creatura che lo avrebbe immediatamente liberato da quegli animali nocivi. Il cuore del re sussultò talmente per la contentezza a questa notizia che gli era stata data che il turbante gli cadde dalla testa. “Portatemi questa creatura,” disse, “questi animali nocivi sono terribili in una corte e se farà ciò che dici, caricherò d’oro e di gioielli la vostra nave in cambio di essa.” L’amministratore, che sapeva il fatto suo, colse al volo l’opportunità di esibire le virtù della micetta. Disse a sua Maestà che non gli sarebbe convenuto separarsi da essa perché, quando se ne fosse andata, i ratti e i topi avrebbero distrutto il carico della nave, ma per fare una cortesia a sua Maestà, sarebbe andato a prenderla. “Correte, correte,” disse la Regina, “sono impaziente di vedere la cara creatura.”

Mentre veniva approntata un’altra cena, l’amministratore se ne andò e tornò con la gatta proprio mentre i ratti e i topi stavano di nuovo divorando tutto. Immediatamente mise giù la gattina, che ne uccise un gran numero.

Il Re fu felice di vedere distrutti i suoi vecchi nemici da una creatura così piccola; la Regina ne fu molto compiaciuta e volle che la gattina le fosse portata vicino per poterla guardare. Al che l’amministratore la chiamò: “Micina, micina, micina!” e venne da lui. Allora l’offrì alla Regina, che indietreggiò, aveva paura di toccare una creatura che avesse portato un tale scompiglio tra i ratti e i topi; in ogni mondo, quando l’amministratore accarezzò la gatta e la chiamò “Micina, micina!” anche la Regina la toccò ed esclamò: “Mastice, mastice!” perché non conosceva l’inglese.

Allora egli la mise in grembo alla Regina dove, facendo le fusa, giocò con la mano di Sua Maestà e poi lei cantò per farla addormentare.

Il Re, avendo visto le prodezze della gattina, e essendo stato informato che i suoi gattini si sarebbero potuti vende in tutto il paese, contrattò con il capitano e con l’amministratore l’intero carico della nave e poi diede loro per la gatta dieci volte tanto quanto ammontava tutto il resto. Al che, prendendo congedo dalle loro Maestà e dagli altri dignitari della corte, essi salparono con il vento favorevole alla volta dell’Inghilterra, dove ora dobbiamo seguirli.

Era appena l’alba quando messer Fitzwarren si alzò per contare l’incasso e organizzare gli affari della giornata. Era appena entrato in ufficio e si era seduto alla scrivania quando qualcuno bussò alla porta. “Chi è là?” disse messe Fitzwarren. “Un amico.” Rispose l’altro. “Quale amico può arrivare a quest’ora inopportuna?” “Un vero amico non è mai inopportuno.” rispose l’altro “vengo a portarvi buone notizie della vostra nave Unicorno.” Il mercante si agitò a tal punto che dimenticò la gotta; aprì immediatamente la porta e chi vide se non il capitano e l’amministratore, con una cassa di gioielli e una polizza di carico davanti ai quali il mercante strabuzzò gli occhi e ringraziò il cielo per avergli concesso un viaggio così fruttuoso. Poi essi gli narrarono le vicende della gatta e gli mostrarono la cassa di gioielli che avevano acquistato per messer Whittington. Al che egli strillò con grande serietà, ma non nella maniera più poetica:

Portatelo qui e ditegli della sua gloria

E chiamatelo messer Whittington per la storia.

Non è affar nostro criticare queste rime; non siamo critic, ma storici: per noi è sufficinete che siano state queste le parole di messer Fitzwarren; e sebbene vada oltre il nostro scopo e forse non sia nelle nostre possibilità dimostrare che fosse un buon poeta, convinceremo ben presto il lettore che era un buon uomo e che aveva un ancor miglior carattere perché quando qualcuno dei presenti gli disse che il tesoro era troppo per un povero ragazzo come Wittington, lui rispose: “Dio non voglia che io lo privi anche di un solo penny; è tutto suo e lo avrà fino all’ultimo centesimo.” Allora ordinò di far venire messer Whittington, che in quel momento stava pulendo la cucina e ricusava di entrare nell’ufficio, dicendo che la stanza era stata spazzata e i suoi scarponi erano chiodati e assai sporchi. In ogni modo il mercante lo fece venire e ordinò che gli fosse portata una sedia. Al che, pensando che intendesse farsi gioco di lui, come era accaduto spesso in cucina, implorò il padrone di non deridere un povero sempliciotto, il quale non intendeva far nulla di male, ma che lo lasciasse alle sue faccende. Prendendolo per mano, il mercante disse: “In verità, messer Whittington, faccio sul serio con voi e vi ho mandato a chiamare per congratularmi per il vostro grande successo. La vostra gatta vi ha procurato di quanto io stesso valga al mondo, e possiate gioirne a lungo ed essere felice!”

Alla fine, avendogli mostrato il Tesoro e essendosi fatto persuadere da lor che gli apparteneva interamente, cadde in ginocchio e ringraziò l’Onnipotente per la provvidenziale assistenza a una creatura così povera e miserabile. Poi sparse tutto il tesoro ai piedi del padrone, che rifiutò di prenderne la benché minima parte; gli disse di essere cordialmente felice per la sua ricchezza e sperava che i beni che aveva acquistato fossero una consolazione per lui e lo rendessero felice. Allora egli si rivolse alla sua padroncina e buona amica, madamigella Alice, la quale rifiutò di prendere nemmeno una moneta, ma gli disse che gioiva di cuore per il suo buon successo e gli augurava tutta la felicità possibile. Poi ringraziò il capitano, l’amministratore e la ciurma della nave per la cura con cui avevano custodito i suoi beni. E inoltre distribuì doni a tutti i servitori della casa, non trascurando neppure la sua vecchia nemica la cuoca, sebbene se lo meritasse assai poco.

Dopo di che messer Fitwarren avvertì messer Whittington di mandare qualcuno a prendere abiti adatti a vestirlo come un gentiluomo e gli offrì di vivere in casa propria finché non se fosse procurata una migliore.

Fu così che il viso di messer Whittington fu lavato, I suoi capelli arricciati e fu rivestito di un ricco completo, il che fece di lui un giovane gentiluomo; e, siccome la ricchezza contribuisce a ridare fiducia a un uomo, in poco tempo abbandonò quei comportamenti dettati principalmente da abbattimento dello spirito, ben presto divenne una compagnia piacevole e vivace tanto che madamigella Alice, la quale in precedenza aveva avuto compassione di lui, ora se ne innamorò.

Quando suo padre si accorse della reciproca attrazione, propose loro il matrimonio, al quale entrambi acconsentirono volentieri, e il Sindaco, i Consiglieri comunali, gli Sceriffi, la compagnia delle Guardie, i membri della reale Accademia d’Arte e un certo numero di eminenti mercanti parteciparono alla cerimonia e furono elegantemente intrattenuti con divertimenti creati allo scopo.

La storia inoltre ci informa che vissero felici e contenti, ebbero molti figli e morirono in tarda età. Messer Whittington fu Sceriffo di Londra e per tre volte Sindaco. Negli ultimi anni del suo mandato intrattenne re Enrico V e la regina, dopo la conquista della Francia, e in tale occasione il Re, in considerazione dei meritit di Whittington, disse. “Mai un principe ha avuto un tale suddito.” Al che, detto a Whittington a tavola, egli rispose: “Mai un suddito ha avuto un tale re.” Sua Maestà, in virtù delle sue buone doti, gli conferì poco dopo l’onore del cavalierato.

Molti anni prima di morire messer Riccardo sostenne costantemente un gran numero di poveri cittadini, costruì una chiesa e una scuola, con un sussidio annuo per gli studenti poveri, e lì vicino fece erigere un ospedale.

Costruì anche la prigione di Newgate per i criminali e fece generose donazioni all’ospedale di san Bartolomeo e ad altri enti pubblici assistenziali.

Origine sconosciuta.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)