The Forty Thieves

(MP3-18' 25'')

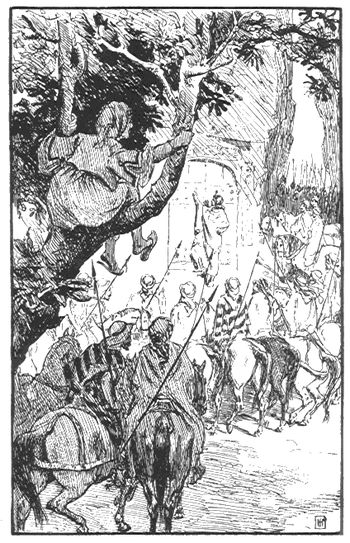

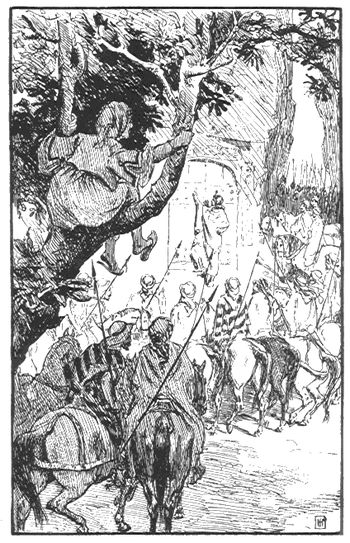

In a town in Persia there dwelt two brothers, one named Cassim, the other Ali Baba. Cassim was married to a rich wife and lived in plenty, while Ali Baba had to maintain his wife and children by cutting wood in a neighboring forest and selling it in the town. One day, when Ali Baba was in the forest, he saw a troop of men on horseback, coming toward him in a cloud of dust. He was afraid they were robbers, and climbed into a tree for safety. When they came up to him and dismounted, he counted forty of them. They unbridled their horses and tied them to trees. The finest man among them, whom Ali Baba took to be their captain, went a little way among some bushes, and said: “Open, Sesame!” so plainly that Ali Baba heard him.

A door opened in the rocks, and having made the troop go in, he followed them, and the door shut again of itself. They stayed some time inside, and Ali Baba, fearing they might come out and catch him, was forced to sit patiently in the tree. At last the door opened again, and the Forty Thieves came out. As the Captain went in last he came out first, and made them all pass by him; he then closed the door, saying: “Shut, Sesame!” Every man bridled his horse and mounted, the Captain put himself at their head, and they returned as they came.

Then Ali Baba climbed down and went to the door concealed among the bushes, and said: “Open, Sesame!” and it flew open. Ali Baba, who expected a dull, dismal place, was greatly surprised to find it large and well lighted, hollowed by the hand of man in the form of a vault, which received the light from an opening in the ceiling. He saw rich bales of merchandise—silk, stuff-brocades, all piled together, and gold and silver in heaps, and money in leather purses. He went in and the door shut behind him. He did not look at the silver, but brought out as many bags of gold as he thought his asses, which were browsing outside, could carry, loaded them with the bags, and hid it all with fagots. Using the words: “Shut, Sesame!” he closed the door and went home.

Then he drove his asses into the yard, shut the gates, carried the money-bags to his wife, and emptied them out before her. He bade her keep the secret, and he would go and bury the gold. “Let me first measure it,” said his wife. “I will go borrow a measure of someone, while you dig the hole.” So she ran to the wife of Cassim and borrowed a measure. Knowing Ali Baba’s poverty, the sister was curious to find out what sort of grain his wife wished to measure, and artfully put some suet at the bottom of the measure. Ali Baba’s wife went home and set the measure on the heap of gold, and filled it and emptied it often, to her great content. She then carried it back to her sister, without noticing that a piece of gold was sticking to it, which Cassim’s wife perceived directly her back was turned. She grew very curious, and said to Cassim when he came home: “Cassim, your brother is richer than you. He does not count his money, he measures it.” He begged her to explain this riddle, which she did by showing him the piece of money and telling him where she found it. Then Cassim grew so envious that he could not sleep, and went to his brother in the morning before sunrise. “Ali Baba,” he said, showing him the gold piece, “you pretend to be poor and yet you measure gold.” By this Ali Baba perceived that through his wife’s folly Cassim and his wife knew their secret, so he confessed all and offered Cassim a share. “That I expect,” said Cassim; “but I must know where to find the treasure, otherwise I will discover all, and you will lose all.” Ali Baba, more out of kindness than fear, told him of the cave, and the very words to use. Cassim left Ali Baba, meaning to be beforehand with him and get the treasure for himself. He rose early next morning, and set out with ten mules loaded with great chests. He soon found the place, and the door in the rock. He said: “Open, Sesame!” and the door opened and shut behind him. He could have feasted his eyes all day on the treasures, but he now hastened to gather together as much of it as possible; but when he was ready to go he could not remember what to say for thinking of his great riches. Instead of “Sesame,” he said: “Open, Barley!” and the door remained fast. He named several different sorts of grain, all but the right one, and the door still stuck fast. He was so frightened at the danger he was in that he had as much forgotten the word as if he had never heard it.

About noon the robbers returned to their cave, and saw Cassim’s mules roving about with great chests on their backs. This gave them the alarm; they drew their sabres, and went to the door, which opened on their Captain’s saying: “Open, Sesame!” Cassim, who had heard the trampling of their horses’ feet, resolved to sell his life dearly, so when the door opened he leaped out and threw the Captain down. In vain, however, for the robbers with their sabres soon killed him. On entering the cave they saw all the bags laid ready, and could not imagine how anyone had got in without knowing their secret. They cut Cassim’s body into four quarters, and nailed them up inside the cave, in order to frighten anyone who should venture in, and went away in search of more treasure.

As night drew on Cassim’s wife grew very uneasy, and ran to her brother-in-law, and told him where her husband had gone. Ali Baba did his best to comfort her, and set out to the forest in search of Cassim. The first thing he saw on entering the cave was his dead brother. Full of horror, he put the body on one of his asses, and bags of gold on the other two, and, covering all with some fagots, returned home. He drove the two asses laden with gold into his own yard, and led the other to Cassim’s house. The door was opened by the slave Morgiana, whom he knew to be both brave and cunning. Unloading the ass, he said to her: “This is the body of your master, who has been murdered, but whom we must bury as though he had died in his bed. I will speak with you again, but now tell your mistress I am come.” The wife of Cassim, on learning the fate of her husband, broke out into cries and tears, but Ali Baba offered to take her to live with him and his wife if she would promise to keep his counsel and leave everything to Morgiana; whereupon she agreed, and dried her eyes.

Morgiana, meanwhile, sought an apothecary and asked him for some lozenges. “My poor master,” she said, “can neither eat nor speak, and no one knows what his distemper is.” She carried home the lozenges and returned next day weeping, and asked for an essence only given to those just about to die. Thus, in the evening, no one was surprised to hear the wretched shrieks and cries of Cassim’s wife and Morgiana, telling everyone that Cassim was dead. The day after Morgiana went to an old cobbler near the gates of the town who opened his stall early, put a piece of gold in his hand, and bade him follow her with his needle and thread.

Having bound his eyes with a handkerchief, she took him to the room where the body lay, pulled off the bandage, and bade him sew the quarters together, after which she covered his eyes again and led him home. Then they buried Cassim, and Morgiana his slave followed him to the grave, weeping and tearing her hair, while Cassim’s wife stayed at home uttering lamentable cries. Next day she went to live with Ali Baba, who gave Cassim’s shop to his eldest son.

The Forty Thieves, on their return to the cave, were much astonished to find Cassim’s body gone and some of their money-bags. “We are certainly discovered,” said the Captain, “and shall be undone if we cannot find out who it is that knows our secret. Two men must have known it; we have killed one, we must now find the other. To this end one of you who is bold and artful must go into the city dressed as a traveler, and discover whom we have killed, and whether men talk of the strange manner of his death. If the messenger fails he must lose his life, lest we be betrayed.” One of the thieves started up and offered to do this, and after the rest had highly commended him for his bravery he disguised himself, and happened to enter the town at daybreak, just by Baba Mustapha’s stall. The thief bade him good-day, saying: “Honest man, how can you possibly see to stitch at your age?” “Old as I am,” replied the cobbler, “I have very good eyes, and will you believe me when I tell you that I sewed a dead body together in a place where I had less light than I have now.” The robber was overjoyed at his good fortune, and, giving him a piece of gold, desired to be shown the house where he stitched up the dead body. At first Mustapha refused, saying that he had been blindfolded; but when the robber gave him another piece of gold he began to think he might remember the turnings if blindfolded as before. This means succeeded; the robber partly led him, and was partly guided by him, right in front of Cassim’s house, the door of which the robber marked with a piece of chalk. Then, well pleased, he bade farewell to Baba Mustapha and returned to the forest. By and by Morgiana, going out, saw the mark the robber had made, quickly guessed that some mischief was brewing, and fetching a piece of chalk marked two or three doors on each side, without saying anything to her master or mistress.

The thief, meantime, told his comrades of his discovery. The Captain thanked him, and bade him show him the house he had marked. But when they came to it they saw that five or six of the houses were chalked in the same manner. The guide was so confounded that he knew not what answer to make, and when they returned he was at once beheaded for having failed. Another robber was dispatched, and, having won over Baba Mustapha, marked the house in red chalk; but Morgiana being again too clever for them, the second messenger was put to death also. The Captain now resolved to go himself, but, wiser than the others, he did not mark the house, but looked at it so closely that he could not fail to remember it. He returned, and ordered his men to go into the neighboring villages and buy nineteen mules, and thirty-eight leather jars, all empty except one, which was full of oil. The Captain put one of his men, fully armed, into each, rubbing the outside of the jars with oil from the full vessel. Then the nineteen mules were loaded with thirty-seven robbers in jars, and the jar of oil, and reached the town by dusk. The Captain stopped his mules in front of Ali Baba’s house, and said to Ali Baba, who was sitting outside for coolness: “I have brought some oil from a distance to sell at to-morrow’s market, but it is now so late that I know not where to pass the night, unless you will do me the favor to take me in.” Though Ali Baba had seen the Captain of the robbers in the forest, he did not recognize him in the disguise of an oil merchant. He bade him welcome, opened his gates for the mules to enter, and went to Morgiana to bid her prepare a bed and supper for his guest. He brought the stranger into his hall, and after they had supped went again to speak to Morgiana in the kitchen, while the Captain went into the yard under pretense of seeing after his mules, but really to tell his men what to do. Beginning at the first jar and ending at the last, he said to each man: “As soon as I throw some stones from the window of the chamber where I lie, cut the jars open with your knives and come out, and I will be with you in a trice.” He returned to the house, and Morgiana led him to his chamber. She then told Abdallah, her fellow-slave, to set on the pot to make some broth for her master, who had gone to bed. Meanwhile her lamp went out, and she had no more oil in the house. “Do not be uneasy,” said Abdallah; “go into the yard and take some out of one of those jars.” Morgiana thanked him for his advice, took the oil pot, and went into the yard. When she came to the first jar the robber inside said softly: “Is it time?”

Any other slave but Morgiana, on finding a man in the jar instead of the oil she wanted, would have screamed and made a noise; but she, knowing the danger her master was in, bethought herself of a plan, and answered quietly: “Not yet, but presently.” She went to all the jars, giving the same answer, till she came to the jar of oil. She now saw that her master, thinking to entertain an oil merchant, had let thirty-eight robbers into his house. She filled her oil pot, went back to the kitchen, and, having lit her lamp, went again to the oil jar and filled a large kettle full of oil. When it boiled she went and poured enough oil into every jar to stifle and kill the robber inside. When this brave deed was done she went back to the kitchen, put out the fire and the lamp, and waited to see what would happen.

In a quarter of an hour the Captain of the robbers awoke, got up, and opened the window. As all seemed quiet, he threw down some little pebbles which hit the jars. He listened, and as none of his men seemed to stir he grew uneasy, and went down into the yard. On going to the first jar and saying, “Are you asleep?” he smelt the hot boiled oil, and knew at once that his plot to murder Ali Baba and his household had been discovered. He found all the gang was dead, and, missing the oil out of the last jar, became aware of the manner of their death. He then forced the lock of a door leading into a garden, and climbing over several walls made his escape. Morgiana heard and saw all this, and, rejoicing at her success, went to bed and fell asleep.

At daybreak Ali Baba arose, and, seeing the oil jars still there, asked why the merchant had not gone with his mules. Morgiana bade him look in the first jar and see if there was any oil. Seeing a man, he started back in terror. “Have no fear,” said Morgiana; “the man cannot harm you: he is dead.” Ali Baba, when he had recovered somewhat from his astonishment, asked what had become of the merchant. “Merchant!” said she, “he is no more a merchant than I am!” and she told him the whole story, assuring him that it was a plot of the robbers of the forest, of whom only three were left, and that the white and red chalk marks had something to do with it. Ali Baba at once gave Morgiana her freedom, saying that he owed her his life. They then buried the bodies in Ali Baba’s garden, while the mules were sold in the market by his slaves. The Captain returned to his lonely cave, which seemed frightful to him without his lost companions, and firmly resolved to avenge them by killing Ali Baba. He dressed himself carefully, and went into the town, where he took lodgings in an inn. In the course of a great many journeys to the forest he carried away many rich stuffs and much fine linen, and set up a shop opposite that of Ali Baba’s son. He called himself Cogia Hassan, and as he was both civil and well dressed he soon made friends with Ali Baba’s son, and through him with Ali Baba, whom he was continually asking to sup with him. Ali Baba, wishing to return his kindness, invited him into his house and received him smiling, thanking him for his kindness to his son. When the merchant was about to take his leave Ali Baba stopped him, saying: “Where are you going, sir, in such haste? Will you not stay and sup with me?” The merchant refused, saying that he had a reason; and, on Ali Baba’s asking him what that was, he replied: “It is, sir, that I can eat no victuals that have any salt in them.” “If that is all,” said Ali Baba, “let me tell you that there shall be no salt in either the meat or the bread that we eat to-night.” He went to give this order to Morgiana, who was much surprised. “Who is this man,” she said, “who eats no salt with his meat?” “He is an honest man, Morgiana,” returned her master; “therefore do as I bid you.” But she could not withstand a desire to see this strange man, so she helped Abdallah to carry up the dishes, and saw in a moment that Cogia Hassan was the robber Captain, and carried a dagger under his garment. “I am not surprised,” she said to herself, “that this wicked man, who intends to kill my master, will eat no salt with him; but I will hinder his plans.”

She sent up the supper by Abdallah, while she made ready for one of the boldest acts that could be thought on. When the dessert had been served, Cogia Hassan was left alone with Ali Baba and his son, whom he thought to make drunk and then to murder them. Morgiana, meanwhile, put on a head-dress like a dancing-girl’s, and clasped a girdle round her waist, from which hung a dagger with a silver hilt, and said to Abdallah: “Take your tabor, and let us go and divert our master and his guest.” Abdallah took his tabor and played before Morgiana until they came to the door, where Abdallah stopped playing and Morgiana made a low courtesy. “Come in, Morgiana,” said Ali Baba, “and let Cogia Hassan see what you can do”; and, turning to Cogia Hassan, he said: “She’s my slave and my housekeeper.” Cogia Hassan was by no means pleased, for he feared that his chance of killing Ali Baba was gone for the present; but he pretended great eagerness to see Morgiana, and Abdallah began to play and Morgiana to dance. After she had performed several dances she drew her dagger and made passes with it, sometimes pointing it at her own breast, sometimes at her master’s, as if it were part of the dance. Suddenly, out of breath, she snatched the tabor from Abdallah with her left hand, and, holding the dagger in her right hand, held out the tabor to her master. Ali Baba and his son put a piece of gold into it, and Cogia Hassan, seeing that she was coming to him, pulled out his purse to make her a present, but while he was putting his hand into it Morgiana plunged the dagger into his heart.

“Unhappy girl!” cried Ali Baba and his son, “what have you done to ruin us?”

“It was to preserve you, master, not to ruin you,” answered Morgiana. “See here,” opening the false merchant’s garment and showing the dagger; “see what an enemy you have entertained! Remember, he would eat no salt with you, and what more would you have? Look at him! he is both the false oil merchant and the Captain of the Forty Thieves.”

Ali Baba was so grateful to Morgiana for thus saving his life that he offered her to his son in marriage, who readily consented, and a few days after the wedding was celebrated with greatest splendor.

At the end of a year Ali Baba, hearing nothing of the two remaining robbers, judged they were dead, and set out to the cave. The door opened on his saying: “Open Sesame!” He went in, and saw that nobody had been there since the Captain left it. He brought away as much gold as he could carry, and returned to town. He told his son the secret of the cave, which his son handed down in his turn, so the children and grandchildren of Ali Baba were rich to the end of their lives.

Arabian Nights.

I quaranta ladri

In una città della Persia vivevano due fratelli, uno si chiamava Cassim e l’altro Ali Baba. Cassim era sposato con una donna ricca e viveva nell’abbondanza mentre Ali Baba doveva mantenere la moglie e i figli tagliando la legna nella vicina foresta e vendendola in città. Un giorno in cui Ali Baba era nella foresta, vide un gruppo di uomini a cavallo venire verso di lui in una nuvola di polvere. Ebbe paura che fossero ladri e per sicurezza si arrampicò su un albero. Quando giunsero presso di lui e smontarono da cavallo, ne contò quaranta. Tolsero le briglie ai cavalli e li legarono agli alberi. Il più imponente tra di loro, che Ali Baba reputò essere il capo, si fece strada tra i cespugli e disse: “Apriti, sesamo!” così chiaramente che Ali Baba lo udì.

Si aprì una porta nelle rocce e, avendo fatto entrare il drappello, egli lo seguì e la porta si richiuse da sola. Rimasero lì dentro per un po’ di tempo e Ali Baba, timoroso che se fosse sceso lo avrebbero catturato, fu obbligato a restare pazientemente sull’albero. Infine la porta si aprì di nuovo e i quaranta ladri uscirono. Il loro capo uscì per primo, così come era entrato per ultimo, e gli altri passarono dopo di lui; allora chiuse la porta, dicendo: “Chiuditi, sesamo!” ogni uomo rimise le briglie al proprio cavallo e montò in sella, il capo si mise alla loro testa e se ne andarono come erano venuti.

Allora Ali Baba scese, andò alla porta nascosta dai cespugli e disse: “Apriti, sesamo!” e la porta si aprì. Ali Baba, che si aspettava un luogo triste e desolato, fu assai sorpreso di scoprire che fosse ampio e ben illuminato, scavato dalla mano dell’uomo in forma di volta che riceveva luce da un’apertura sul soffitto. Vide ricche balle di mercanzia… sete e broccati tutti accatastati, e mucchi d’oro e d’argento e denaro in borse di pelle. Entrò e la porta si chiuse dietro di lui. Non guardò l’argento, ma prese quante più borse d’oro pensò i suoi asini, che stavano brucando fuori, potessero portare, li caricò delle borse e le nascose con le fascine. Servendosi delle parole: “Chiuditi, sesamo!” chiuse la porta e tornò a casa.

Allora condusse gli asini in cortile, chiuse i cancelli, portò le borse di denaro alla moglie e le svuotò dinnanzi a lei. Le ordinò di mantenere il segreto e lui sarebbe andato a seppellire l’oro. “Prima lasciamelo pesare,” disse la moglie “andrò a prendere in prestito da qualcuno un dosatore mentre tu scavi la buca.” Così corse dalla moglie di Cassim e prese in prestito un dosatore. Conoscendo la povertà di Ali Baba, la sorella era curiosa di scoprire che tipo di grano sua moglie dovesse pesare e mise astutamente un po’ di grasso sul fondo del dosatore. La moglie di Ali Baba tornò a casa e immerse il dosatore nel mucchio d’oro e lo riempì e lo vuotò con gran contentezza. Poi lo riportò alla sorella, senza rendersi conto che vi era rimasto attaccato un pezzo d’oro, cosa di cui si accorse subito la moglie di Cassim appena le fu restituito. Divenne assai curiosa e quando Cassim tornò a casa, gli disse: “Cassim, tuo fratello è più ricco di te. Non conta le monete, le pesa.” Lui la pregò di spiegargli questo mistero, cosa che lei fece mostrandogli la moneta d’oro e dicendogli dove l’aveva trovata. Allora Cassim diventò così invidioso da non poter dormire e la mattina prima dell’alba andò dal fratello. “Ali Baba,” gli disse, mostrandogli la moneta d’oro, “fingi di essere povero eppure pesi l’oro.” Da ciò Ali Baba comprese che per la follia della moglie Cassim e sua moglie conoscevano il loro segreto, così confessò tutto e offrì una parte a Cassim. “È ciò che mi aspetto,” disse Cassim, “ma devo sapere dove hai trovato il tesoro, altrimenti scoprirò tutto e tu perderai tutto.” Ali Baba, più per gentilezza che per paura, gli raccontò della caverna e delle esatte parole da usare. Cassim lasciò Ali Baba, con l’intenzione di arrivare prima di lui e prendere per se stesso il tesoro. Il mattino seguente si alzò presto e partì con dieci muli caricati di grossi cesti. Ben presto trovò il posto e la porta nella roccia. Disse: “Apriti, sesamo!” e la porta si aprì e si chiuse dietro di lui. Avrebbe voluto lustrarsi gli occhi per tutto il giorno con il tesoro, ma si affrettò ad ammucchiarne quanto più possibile; quando fu pronto per andarsene non poté rammentare ciò che doveva dire perché stava pensando alle sue grandi ricchezze. Invece di “sesamo!” disse: “Apriti, orzo!” e la porta restò chiusa. Nominò diversi tipi di semi tranne quello giusto e la porta restava ben chiusa. Era così spaventato per il pericolo in cui si trovava che aveva dimenticato la parola come se non l’avesse mai sentita.

Verso mezzogiorno i ladri tornarono nella loro caverna e videro i muli di Cassim che brucavano lì vicino con le grandi ceste sul dorso. Ciò li insospettì; sguainarono le sciabole e andarono alla porta, che si aprì alla frase del capo: “Apriti, sesamo!”. Cassim, che aveva sentito il calpestio degli zoccoli dei cavalli, decise di vendere cara la pelle così quando la porta si aprì, saltò e trascinò giù il capo. Invano, in ogni modo, perché i ladri lo uccisero subito con le sciabole. Entrando nella caverna, videro tutte le borse pronte e non potevano immaginare in quale modo qualcuno fosse entrato senza conoscere il loro segreto. Tagliarono il corpo di Cassim in quattro pezzi e li inchiodarono all’interno della caverna, in modo tale da spaventare chiunque vi si avventurasse, e andarono via in cerca di altri tesori.

Quando calò la notte la moglie di Cassim diventò ansiosa e corse dal cognato a dirgli dove fosse andato il marito. Ali Baba fece del proprio meglio per confortarla e andò nella foresta in cerca di Cassim. La prima cosa che vide entrando nella caverna fu il fratello morto. Pieno di orrore caricò il corpo su uno dei suoi asini e le borse d’oro sugli altri due e, coprendo tutto con delle fascine, tornò a casa. Condusse nel proprio cortile i due asini carichi d’oro e portò l’altro a casa di Cassim. La porta fu aperta dalla schiava Morgiana, che lui sapeva essere coraggiosa e astuta. Scaricando l’asino, le disse: “Questo è il corpo del tuo padrone, che è stato assassinato, ma che dobbiamo seppellire come se fosse morto nel suo letto. Ne parleremo ancora, ma per adesso di’ alla tua padrona che sono arrivato.” La moglie di Cassim, apprendendo la sorte del marito, scoppiò in grida e lacrime, ma Ali Baba si offrì di prenderla a vivere con sé e con la moglie se lei avesse promesso di accettare i suoi consigli e affidare tutto a Morgiana, al che lei accettò e si asciugò gli occhi.

Nel frattempo Morgiana era andata in cerca di uno speziale e gli aveva chiesto alcune pastiglie. “Il mio povero padrone” disse “non può né mangiare né parlare e nessuno sa malanno sia.” Portò a casa le pastiglie e il giorno successivo tornò piangendo, e chiese un’essenza di quelle per chi era in fin di vita. Così la sera nessuno si sorprese di sentire le acute grida della moglie di Cassim e di Morgiana, che dicevano a ognuno che Cassim era morto. Il giorno dopo Morgiana andò da un vecchio calzolaio vicino ai cancelli della città, il quale apriva presto la bottega, gli mise in mano un pezzo d’oro e gli disse di seguirla con ago e filo.

Avendogli bendato gli occhi con un fazzoletto, lo condusse nella stanza in cui giaceva il corpo, tolse le bende e gli disse di cucire insieme i pezzi, dopodiché gli coprì di nuovo gli occhi e lo ricondusse a casa. Poi seppellirono Cassim e la sua schiava Morgiana lo seguì nella tomba, piangendo e strappandosi i capelli, mentre la moglie di Cassim stava in casa emettendo grida di dolore. Il giorno seguente andò a vivere con Ali Baba, che diede la bottega di Cassim al figlio maggiore.

Di ritorno alla caverna i quaranta ladri rimasero attoniti nello scoprire che erano spariti il corpo di Cassim e un po’ di borse d’oro. “Siamo stati di certo scoperti” disse il capo “e saremo rovinati se non troveremo chi conosce il nostro segreto. Lo devono sapere due uomini; uno lo abbiamo ucciso, dobbiamo trovare l’altro. A tale scopo uno di voi che sia audace e scaltro dovrà andare in città travestito da viaggiatore e scoprire chi abbiamo ucciso e se si parli della sua strana morte. Se il messaggero fallirà, perderà la vita, in modo tale che non saremo traditi.” Uno dei ladri si alzò e si offrì di fare ciò e, dopo che il resto del gruppo l’ebbe grandemente lodato per il suo coraggio, si travestì e fece in modo di entrare in città all’alba proprio presso la bottega di Baba Mustafa. Il ladro gli diede il buongiorno, dicendo: “Brav’uomo, come è possibile che vediate i punti alla vostra età?” “Per quanto sia vecchio,” rispose il calzolaio “ho occhi molto buoni e dovete credermi se vi dico che ho cucito un cadavere fatto a pezzi in un posto in cui c’era meno luce di quanta ce ne sia ora.” Il ladro fu contento della propria buona sorte e, dandogli un pezzo d’oro, espresse il desiderio che gli mostrasse la casa in cui aveva rimesso insieme il cadavere. Dapprima Mustafa rifiutò, dicendo di essere stato bendato, ma quando il ladro gli diede un altro pezzo d’oro cominciò a pensare che avrebbe rammentato il percorso se fosse stato bendato come la volta precedente. E fu quel che successe; il ladro un po’ lo condusse e un po’ fu guidato da lui fin davanti alla casa di Cassim, la cui porta segnò con un pezzo di gesso. Poi, soddisfatto, si congedò da Baba Mustafa e tornò nella foresta. Nel frattempo Morgiana, uscendo, vide il segno che il ladro aveva fatto, pensò rapidamente che si trattasse di qualche guaio e, prendendo un pezzo di gesso, segnò altre due o tre porte da ogni parte, senza dire niente al padrone o alla padrona.

Intanto il ladro aveva riferito al capo la propria scoperta. Il capo lo ringraziò e gli ordinò di mostrargli la casa che aveva segnato. Ma quando giunsero, videro che altre cinque o sei case erano segnate con il gesso nel medesimo modo. La guida fu così confusa che non seppe che cosa rispondere e quando tornarono, fu subito decapitata per aver fallito. Fu inviato un altro ladro e, avendo persuaso Baba Mustafa, segnò la casa con il gessò rosso; ma Morgiana fu di trovo troppo furba per loro e anche il secondo messaggero fu messo a morte. Il capo decise di andarci in persona ma, più saggio degli altri, non segnò la casa ma la guardò così attentamente da non potersi sbagliare nel rammentarla. Tornò e ordinò agli uomini di andare nei villaggi vicini e comperare diciannove muli e trentotto grosse giare, tutte vuote, eccetto una che fu riempita d’olio. Il capo fece nascondere in ognuna uno dei suoi uomini armato, strofinando l’esterno della giara con l’olio dell’unica piena. Poi i diciannove muli furono condotti con i trentasette ladri nelle giare e la giara d’olio in città verso sera. Il capo fermò i muli di fronte alla casa di Ali Baba e al quale disse, mentre era seduto fuori al fresco: “Ho portato da lontano un po’ d’olio da vendere al mercato di domani, ma adesso è così tardi che non so dove trascorrere la notte, a meno che non mi facciate il favore di accogliermi.” Sebbene Ali Baba avesse visto nella foresta il capo dei ladri, non lo riconobbe per via del travestimento da mercante d’olio. Gli diede il benvenuto, aprì i cancelli per far entrare i muli e andò a dire a Morgiana di preparare un letto e la cena per l’ospite. Condusse lo straniero in sala e, dopo che ebbero cenato, andò di nuovo a parlare con Morgiana in cucina mentre il capo andava in cortile con la scusa di dare un’occhiata ai muli ma in realtà per dire ai propri uomini che cosa fare. Cominciando dalla prima giara e finendo con l’ultima, disse a ciascun uomo: “Appena avrò gettato alcune pietre fuori dalla finestra della camera in cui dormo, aprite con i vostri coltelli l’imboccatura delle giare e uscite, e io mi unirò a voi in un attimo.” Tornò in casa e Morgiana lo condusse nella sua camera. Poi disse ad Abdallah, suo compagno di schiavitù, di mettere su la pentola per preparare un po’ di brodo per il padrone, che era andato a letto. Nel frattempo prese la lampada e in casa non c’era più olio. “Non è un problema£ disse Abdallah “va’ in cortile e prendine un po’ da una di quelle giare.” Morgiana lo ringraziò per il suggerimento, prese il vaso dell’olio e andò in cortile. Quando raggiunse la prima giara, il ladro all’interno disse a bassa voce: “È ora?”

Qualunque altro schiavo che non fosse Morgiana, trovando un uomo nella giara invece dell’olio, avrebbe gridato e fatto rumore, ma lei, sapendo che il padrone fosse in pericolo, architettò un piano e rispose sottovoce: “Non ancora, ma tra poco.” Andò presso tutte le giare, dando la medesima risposta, finché giunse alla giara con l’olio. Adesso aveva visto che il suo padrone, credendo di ospitare un mercante d’olio, si era portato in casa trent’otto ladri. Riempì d’olio il vaso, tornò in cucina e, avendo acceso la lampada, tornò di nuovo alla giara d’olio e riempì fino all’orlo un grande bollitore. Quando bollì, andò e versò abbastanza olio dentro ciascuna giara da soffocare e uccidere il ladro all’interno. Quando ebbe compiuto questo coraggioso gesto, tornò in cucina, spense il fuoco e la lampada e rimase a vedere che cosa sarebbe successo.

Di lì a un quarto d’ora il capo dei ladri si svegliò, si alzò e aprì la finestra. Siccome tutto sembrava tranquillo, gettò fuori alcuni piccoli ciottoli che colpirono le giare. Ascoltò e siccome nessuno dei suoi uomini sembrava si muovesse, si sentì inquieto e andò in cortile. Avvicinandosi alla prima giara e dicendo: “Stai dormendo?” sentì l’odore di olio bollito e seppe subito che il suo piano di uccidere Ali Baba e gli abitanti della casa era stato scoperto. Trovò tutta i membri della banda morti e, dalla sparizione dell’olio nella prima giara, compresa in quale maniera fosse avvenuto. Allora forzò la serratura di una porta che conduceva in giardino e fuggì, arrampicandosi sui muri. Morgiana sentì e vide tutto ciò e, lieta del proprio successo, andò a letto e si addormentò.

All’alba Ali Baba si alzò e, vedendo le giare d’olio ancora lì, chiese perché il mercante non se ne fosse andato con i suoi muli. Morgiana gli disse di guardare nella prima giara e vedere se vi fosse dell’olio. Vedendo un uomo, arretrò per lo spavento. “Non temere” disse Morgiana “l’uomo non può farti del male, è morto.” Ali Baba, quando si fu ripreso dallo sbalordimento, chiese che cosa ne fosse stato del mercante. “Mercante!” disse Morgiana “Non era un mercante più di me!” e gli raccontò tutta la storia, assicurandogli che era stato un complotto dei ladri della foresta, dei quali erano rimasti solo tre e che i segni di gesso bianco e rosso avevano qualcosa che fare con ciò. Ali Baba restituì subito a Morgiana la libertà, dicendole che le doveva la vita. Poi seppellirono i corpi nel giardino di Ali Baba mentre i muli furono venduti al mercato dai suoi schiavi. Il capo tornò nella caverna solitaria, che gli sembrava spaventosa senza i compagni, e decise con fermezza che li avrebbe vendicati uccidendo Ali Baba. Si vestì con cura e andò in città, dove prese alloggio in una locanda. In seguito a una gran quantità di viaggi nella foresta, portò via molte ricche stoffe e molti belle pezze di lino e aprì una bottega di fronte a quella del figlio di Ali Baba. Si diede nome Cogia Hassan e, siccome era educato e ben vestito, fece presto amicizia con il figlio di Ali Baba, e attraverso di lui con Ali Baba , al quale chiedeva continuamente di cenare con lui. Ali Baba, desiderando ricambiare la gentilezza, lo invitò a casa propria e lo ricevette sorridendo, ringraziandolo per la gentilezza verso suo figlio. Quando il mercante stava per congedarsi, Ali Baba lo fermò, dicendogli: “Dove state andando, signore, con tanta fretta? Non volete restare a cena con me?” il mercante rifiutò, dicendo di avere un motivo e, avendogli chiesto Ali Baba quale fosse, rispose: “Signore, il fatto è che non posso mangiare cibi che contengano sale.” “Se è tutto qui” disse Ali Baba “lasciatemi dire che non ci sarà sale né nella carne né nel pane che mangeremo stasera.” E andò a dare l’ordine a Morgiana che apparve molto sorpresa. Chiese: “Chi è quest’uomo che mangia carne senza sale?” “È un uomo onesto, Morgiana” rispose il padrone “perciò fai come ti ho detto.” Lei non seppe resistere al desiderio di vedere questo strano uomo, così aiutò Abdallah a portare i piatti e si accorse subito che Cogia Hassan era il capo dei ladri e portava un pugnale sotto il vestito. ‘Non sono sorpresa’ si disse ‘che questo uomo malvagio, che vuole uccidere il mio padrone, non voglia mangiare salato con lui; intralcerò i suoi piani.’

Fece servire la cena da Abdallah mentre si preparava a uno dei più audaci gesti che si potessero pensare. Quando fu servito il dolce, Cogia Hassan fu lasciato solo con Ali Baba e suo figlio, che pensava di far ubriacare e poi di uccidere. Nel frattempo Morgiana si era abbigliata da danzatrice, si allacciò alla vita una cintura, dalla quale pendeva un pugnale con l’impugnatura d’argento, e disse ad Abdallah; “Prendi il tuo tamburello e andiamo a intrattenere il padrone e il suo ospite.” Abdallah prese il tamburello e suonò davanti a Morgiana finché giunsero alla porta, dove Abdallah smise di suonare e Morgiana fece un profondo inchino. “Entra, Morgiana” disse Ali Baba “e mostra a Corgia Hassan che cosa sai fare.” E rivolgendosi a Corgia Hassan, disse: “Lei è la mia schiava e la mia governante.” Corgia Hassan non era contento perché temeva che per il momento fosse rimandata la possibilità di uccidere Ali Baba, ma finse un gran desiderio di vedere Morgiana e Abdallah cominciò a suonare e Morgiana a danzare. Dopo che si fu esibita in varie danze, estrasse il pugnale e fece dei gesti con esso, a volte puntandoselo contro il petto, a volte contro quello del padrone, come se facessero parte della danza. Improvvisamente, senza fiato, afferrò il tamburello di Abdallah con la mano sinistra e, tenendo il pugnale con la destra, lo porse al padrone. Ali Baba e suo figlio vi misero un pezzo d’oro e Cogia Hassan, vedendo che lei si stava avvicinando, tirò fuori la borsa per farle un omaggio, ma mentre vi stava infilando la mano, Morgiana gli piantò il pugnale nel cuore.

“Ragazza infelice!” gridarono Ali Baba e suo figlio, “Che cos’hai fatto per rovinarci?”

“L’ho fatto per salvarvi, padrone, non per rovinarvi.” rispose Morgiana “Guardate qui,” disse aprendo il vestito del falso mercante e mostrando il pugnale “guardate che razza di nemico avete intrattenuto! Rammentate, non voleva mangiare il sale con voi e che altro volete? Guardatelo! Lui è sia il falso mercante d’olio che il capo dei quaranta ladri.”

Ali Baba fu così grato a Morgiana per avergli salvato la vita che le offrì di sposare il proprio figlio, il quale acconsentì volentieri, e pochi giorni dopo le nozze furono celebrate con la più grande magnificenza.

Dopo un anno Ali Baba, non sentendo più notizie dei due ladri rimanenti, ritenne che fossero morti e andò alla caverna. La porta si aprì alla frase: “Apriti, sesamo!”. Entrò e vide che nessuno vi era entrato dopo che il capo l’aveva lasciata. Prese tanto oro quanto ne poté portare e tornò in città. Rivelò al figlio il segreto della caverna affinché vi andasse a propria volta e così i figli e i nipoti di Ali Baba furono ricchi fino alla fine dei loro giorni.

Da Le mille e una notte.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)