There was once upon a time a peasant called Masaniello who had twelve daughters. They were exactly like the steps of a staircase, for there was just a year between each sister. It was all the poor man could do to bring up such a large family, and in order to provide food for them he used to dig in the fields all day long. In spite of his hard work he only just succeeded in keeping the wolf from the door, and the poor little girls often went hungry to bed.

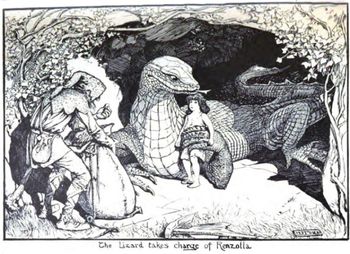

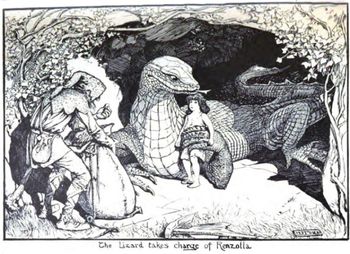

One day, when Masaniello was working at the foot of a high mountain, he came upon the mouth of a cave which was so dark and gloomy that even the sun seemed afraid to enter it. Suddenly a huge green lizard appeared from the inside and stood before Masaniello, who nearly went out of his mind with terror, for the beast was as big as a crocodile and quite as fierce looking.

But the lizard sat down beside him in the most friendly manner, and said: 'Don't be afraid, my good man, I am not going to hurt you; on the contrary, I am most anxious to help you.'

When the peasant heard these words he knelt before the lizard and said: 'Dear lady, for I know not what to call you, I am in your power; but I beg of you to be merciful, for I have twelve wretched little daughters at home who are dependent on me.'

'That's the very reason why I have come to you,' replied the lizard. 'Bring me your youngest daughter to-morrow morning. I promise to bring her up as if she were my own child, and to look upon her as the apple of my eye.'

When Masaniello heard her words he was very unhappy, because he felt sure, from the lizard's wanting one of his daughters, the youngest and tenderest too, that the poor little girl would only serve as dessert for the terrible creature's supper. At the same time he said to himself, 'If I refuse her request, she will certainly eat me up on the spot. If I give her what she asks she does indeed take part of myself, but if I refuse she will take the whole of me. What am I to do, and how in the world am I to get out of the difficulty?'

As he kept muttering to himself the lizard said, 'Make up your mind to do as I tell you at once. I desire to have your youngest daughter, and if you won't comply with my wish, I can only say it will be the worse for you.'

Seeing that there was nothing else to be done, Masaniello set off for his home, and arrived there looking so white and wretched that his wife asked him at once: 'What has happened to you, my dear husband? Have you quarrelled with anyone, or has the poor donkey fallen down?'

'Neither the one nor the other,' answered her husband,' but something far worse than either. A terrible lizard has nearly frightened me out of my senses, for she threatened that if I did not give her our youngest daughter, she would make me repent it. My head is going round like a mill-wheel, and I don't know what to do. I am indeed between the Devil and the Deep Sea . You know how dearly I love Renzolla, and yet, if I fail to bring her to the lizard to-morrow morning, I must say farewell to life. Do advise me what to do.'

When his wife had heard all he had to say, she said to him: 'How do you know, my dear husband, that the lizard is really our enemy? May she not be a friend in disguise? And your meeting with her may be the beginning of better things and the end of all our misery. Therefore go and take the child to her, for my heart tells me that you will never repent doing so.'

Masaniello was much comforted by her words, and next morning as soon as it was light he took his little daughter by the hand and led her to the cave.

The lizard, who was awaiting the peasant's arrival, came forward to meet him, and taking the girl by the hand, she gave the father a sack full of gold, and said: 'Go and marry your other daughters, and give them dowries with this gold, and be of good cheer, for Renzolla will have both father and mother in me; it is a great piece of luck for her that she has fallen into my hands.'

Masaniello, quite overcome with gratitude, thanked the lizard, and returned home to his wife.

As soon as it was known how rich the peasant had become, suitors for the hands of his daughters were not wanting, and very soon he married them all off; and even then there was enough gold left to keep himself and his wife in comfort and plenty all their days.

As soon as the lizard was left alone with Renzolla, she changed the cave into a beautiful palace, and led the girl inside. Here she brought her up like a little princess, and the child wanted for nothing. She gave her sumptuous food to eat, beautiful clothes to wear, and a thousand servants to wait on her.

Now, it happened, one day, that the king of the country was hunting in a wood close to the palace, and was overtaken by the dark. Seeing a light shining in the palace he sent one of his servants to ask if he could get a night's lodging there.

When the page knocked at the door the lizard changed herself into a beautiful woman, and opened it herself. When she heard the king's request she sent him a message to say that she would be delighted to see him, and give him all he wanted.

The king, on hearing this kind invitation, instantly betook himself to the palace, where he was received in the most hospitable manner. A hundred pages with torches came to meet him, a hundred more waited on him at table, and another hundred waved big fans in the air to keep the flies from him. Renzolla herself poured out the wine for him, and, so gracefully did she do it, that his Majesty could not take his eyes off her.

When the meal was finished and the table cleared, the king retired to sleep, and Renzolla drew the shoes from his feet, at the same time drawing his heart from his breast. So desperately had he fallen in love with her, that he called the fairy to him, and asked her for Renzolla's hand in marriage. As the kind fairy had only the girl's welfare at heart, she willingly gave her consent, and not her consent only, but a wedding portion of seven thousand golden guineas.

The king, full of delight over his good fortune, prepared to take his departure, accompanied by Renzolla, who never so much as thanked the fairy for all she had done for her. When the fairy saw such a base want of gratitude she determined to punish the girl, and, cursing her, she turned her face into a goat's head. In a moment Renzolla's pretty mouth stretched out into a snout, with a beard a yard long at the end of it, her cheeks sank in, and her shining plaits of hair changed into two sharp horns. When the king turned round and saw her he thought he must have taken leave of his senses. He burst into tears, and cried out: 'Where is the hair that bound me so tightly, where are the eyes that pierced through my heart, and where are the lips I kissed? Am I to be tied to a goat all my life? No, no! nothing will induce me to become the laughing-stock of my subjects for the sake of a goat-faced girl!' When they reached his own country he shut Renzolla up in a little turret chamber of his palace, with a waiting-maid, and gave each of them ten bundles of flax to spin, telling them that their task must be finished by the end of the week.

The maid, obedient to the king's commands, set at once to work and combed out the flax, wound it round the spindle, and sat spinning at her wheel so diligently that her work was quite done by Saturday evening. But Renzolla, who had been spoilt and petted in the fairy's house, and was quite unaware of the change that had taken place in her appearance, threw the flax out of the window and said: 'What is the king thinking of that he should give me this work to do? If he wants shirts he can buy them. It isn't even as if he had picked me out of the gutter, for he ought to remember that I brought him seven thousand golden guineas as my wedding portion, and that I am his wife and not his slave. He must be mad to treat me like this.'

All the same, when Saturday evening came, and she saw that the waiting-maid had finished her task, she took fright lest she should be punished for her idleness. So she hurried off to the palace of the fairy, and confided all her woes to her. The fairy embraced her tenderly, and gave her a sack full of spun flax, in order that she might show it to the king, and let him see what a good worker she was. Renzolla took the sack without one word of thanks, and returned to the palace, leaving the kind fairy very indignant over her want of gratitude.

When the king saw the flax all spun, he gave Renzolla and the waiting-maid each a little dog, and told them to look after the animals and train them carefully.

The waiting-maid brought hers up with the greatest possible care, and treated it almost as if it were her son. But Renzolla said: 'I don't know what to think. Have I come among a lot of lunatics? Does the king imagine that I am going to comb and feed a dog with my own hands?' With these words she opened the window and threw the poor little beast out, and he fell on the ground as dead as a stone.

When a few months had passed the king sent a message to say he would like to see how the dogs were getting on. Renzolla, who felt very uncomfortable in her mind at this request, hurried off once more to the fairy. This time she found an old man at the door of the fairy's palace, who said to her: 'Who are you, and what do you want?'

When Renzolla heard his question she answered angrily: 'Don't you know me, old Goat-beard? And how dare you address me in such a way?'

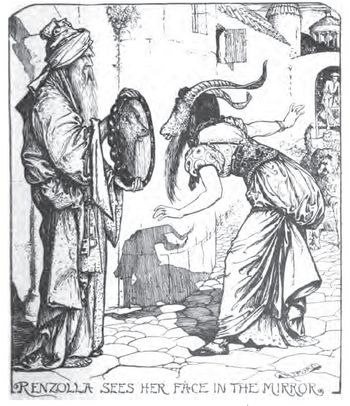

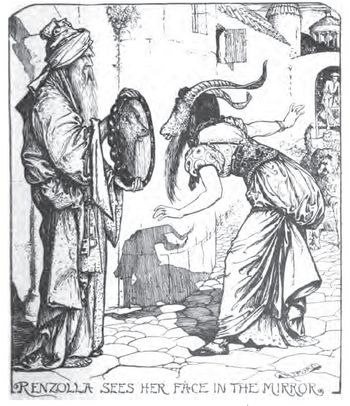

'The pot can't call the kettle black ,' answered the old man, 'for it is not I, but you who have a goat's head. Just wait a moment, you ungrateful wretch, and I will show you to what a pass your want of gratitude has brought you.'

With these words he hurried away, and returned with a mirror, which he held up before Renzolla. At the sight of her ugly, hairy face, the girl nearly fainted with horror, and she broke into loud sobs at seeing her countenance so changed.

Then the old man said: 'You must remember, Renzolla, that you are a peasant's daughter, and that the fairy turned you into a queen; but you were ungrateful, and never as much as thanked her for all she had done for you. Therefore she has determined to punish you. But if you wish to lose your long white beard, throw yourself at the fairy's feet and implore her to forgive you. She has a tender heart, and will, perhaps, take pity on you.'

Renzolla, who was really sorry for her conduct, took the old man's advice, and the fairy not only gave her back her former face, but she dressed her in a gold embroidered dress, presented her with a beautiful carriage, and brought her back, accompanied by a host of servants, to her husband. When the king saw her looking as beautiful as ever, he fell in love with her once more, and bitterly repented having caused her so much suffering.

So Renzolla lived happily ever afterwards, for she loved her husband, honoured the fairy, and was grateful to the old man for having told her the truth.

From the Italian. Kletke.

La ragazza con la faccia di capra

C’era una volta un contadino chiamato Masaniello che aveva dodici figlie. Erano esattamente come gli scalini di una scala perché c’era solo un anno tra ciascuna sorella. Il pover’uomo faceva di tutto per allevare una così vasta famiglia, e per procurare loro il cibo era solito zappare nei campi per tutto il giorno. Malgrado il duro lavoro, a malapena sbarcava il lunario e le povere ragazzine spesso andavano a letto affamate.

Un giorno in cui Masaniello stava lavorando ai piedi di un’alta montagna, arrivò all’imboccatura di una grotta così buia e tetra in cui perfino il sole sembrava avesse paura di entrare. Improvvisamente apparve dall’interno un’enorme lucertola verde e si fermò davanti a Masaniello, il quale per poco non uscì di senno per la paura perché la bestia era grossa come un coccodrillo e quasi altrettanto feroce alla vista.

Ma la lucertola sedette accanto a lui nel modo più amichevole e disse. “Non aver paura, buon’uomo, non ti voglio far del male; al contrario, sono assai ansiosa di aiutarti.”

Quando il contadino udì queste parole, si inginocchiò davanti alla lucertola e disse: “Mia cara dama, poiché non so che cosa chiedervi, sono in vostro potere; ma vi prego di avere pietà perché ho dodici infelici figliolette a casa che dipendono da me.”

”È questa la vera ragione per la quale sono venuta da te,” replicò la lucertola. “Domani mattina portami la tua figlia più piccola. Ti prometto che la terrò come fosse mia figlia e di custodirla come la pupilla dei miei occhi.”

Quando Masaniello udì queste parole, fu molto infelice, perché era sicuro, dato che la lucertola voleva una delle sue figlie, oltretutto la più giovane e la più delicata, che la povera bambina sarebbe diventata il dessert per la cena della terribile creatura. Nel medesimo tempo diceva a se stesso: “Se respingo la sua richiesta, certamente mi mangerà su due piedi. Se le do ciò che chiede, in effetti è come se prendesse una parte di me, ma se rifiuto, mi mangerà tutto intero. Che cosa devo fare, e in che modo potrò tirarmi fuori da questa difficoltà?”

Mentre borbottava così tra sé, la lucertola disse: “Decidi subito su ciò che ti ho detto. Desidero avere la tua figlia minore e se non intendi esaudire il mio desiderio, posso solo dirti che sarà peggio per te.”

Dato che non c’era altro da fare, Masaniello si mise in cammino verso casa, e vi arrivò così pallido e infelice che la moglie gli chiese subito: “Che cosa ti è successo, mio caro marito? Hai litigato con qualcuno o il povero asino è caduto?”

”Né l’una né l’altra cosa,” rispose il marito, “Ma qualcosa di peggio di entrambe. Una terribile lucertola mi ha quasi spaventato a morte perché ha minacciato che, se non le darò la nostra figlia minore, me ne farà pentire. La testa mi gira come la ruota di un mulino, e non so che cosa fare. Sono fra l’incudine e il martello (1). Sai quanto io ami teneramente Renzolla, e con tutto ciò, se non la porterò domattina dalla lucertola, dovrò rinunciare alla vita. Consigliami che cosa fare.”

Quando la moglie ebbe udito tutto ciò che aveva da dirle, gli disse: “Come puoi sapere, mio c aro marito, che la lucertola sia davvero tua nemica? Non potrebbe essere un’amica sotto mentite spoglie? E il tuo incontro con lei potrebbe essere l’inizio di buone cose e la fine di tutta la nostra miseria. Dunque va’ e portale la bambina, perché il cuore mi dice che non dovrai mai pentirtene.”

Masaniello fu molto confortato dalle sue parole, e la mattina successiva, appena fece giorno, prese la figlioletta per mano e la condusse alla caverna.

La lucertola, che stava spettando l’arrivo del contadino, venne fuori ad incontrarlo e, prendendo per mano la ragazzina, diede al padre un sacco pieno d’oro e disse: “Va’ e fai sposare le tue figlie, dando loro in dote quest’oro, e stai di buon animo perché Renzolla troverà in me un padre e una madre; è una gran fortuna per lei essere finita nelle mie mani.”

Masaniello, quasi sopraffatto dalla riconoscenza, ringraziò la lucertola e tornò a casa dalla moglie.

Appena si seppe come fosse diventato ricco il contadino, non mancarono pretendenti alla mano delle sue figlie e assai presto le vide tutte sposate; e tuttavia era rimasto abbastanza oro per mantenere lui e la moglie nelle comodità e nell’abbondanza fino alla fine dei loro giorni.

Appena la lucertola rimase sola con Renzolla, trasformò la caverna in un meraviglioso palazzo e vi condusse la fanciulla. Lì la allevò come una piccola principessa e alla bambina non mancava nulla. Le diede cibo raffinato da mangiare, splendidi abiti da indossare e un migliaio di domestiche a servirla.

Allora un giorno accadde che il re del paese stesse cacciando in un bosco vicino al palazzo e fosse sorpreso dal buio. Vedendo una luce brillare ne l palazzo, mando i servi a chiedere se potessero alloggiarlo per quella notte.

Quando il paggio bussò alla porta, la lucertola si trasformò in una splendida donna e aprì ella stessa. Quando udì la richiesta del re, gli mandò un messaggio in cui diceva che sarebbe stata lietissima di vederlo e che gli avrebbe offerto tutto ciò che voleva.

Ricevendo questo gentile invito, il re si recò subito a palazzo e fu ricevuto nel modo più ospitale. Un centinaio di paggi con le torce gli andarono incontro, più di cento lo aspettavano a tavola e altri cento agitavano grandi ventagli in aria per allontanare da lui le mosche. La stessa Renzolla gli servì il vino e lo fece con tale grazia che sua Maestà non poté toglierle gli occhi dosso.

Quando il pasto fu terminato e la tavola sparecchiata, il re si ritirò a dormire e Renzolla gli sfilò le scarpe dai piedi, rubandogli nel medesimo tempo il cuore dal petto. Si innamorò così perdutamente di lei che chiamò la fata e chiese la mano di Renzolla. Siccome la gentile fata aveva a cuore solo il benessere della fanciulla, diede volentieri il consenso, e non solo quello, ma anche una dote matrimoniale di settemila ghinee (2) d’oro.

Il re, al colmo della gioia per la propria buona fortuna, si preparò a partire, accompagnato da Renzolla, la quale neppure ringraziò la fata per tutto ciò che aveva fatto per lei. Quando la fata vide una tale mancanza di gratitudine, decise di punire la ragazza e, maledicendola, mutò il suo volto in una testa di capra. In un attimo la graziosa bocca di Renzolla si distorse in un grugno, con una lunga barba all’estremità, le guance calarono e la sua splendida treccia di capelli si mutò in due corna affilate. Quando il re si girò e la vide, pensò di essere uscito di senno. Scoppiò in lacrime e gridò: “Dove sono i capelli che mi hanno avvinto così saldamente, dove sono gli occhi che hanno trafitto il mio cuore e dove sono le labbra che ho baciato? Sarò legato a una capra per tutta la vita? No, no! Niente mi indurrà a diventare lo zimbello dei miei sudditi per una ragazza dal muso di capra!

Quando ebbero raggiunto il paese del re, egli rinchiuse Renzolla nella camera di una torretta del palazzo, con una cameriera personale, dando a ciascuna di loro dieci fasci di lino da filare e dicendo che il lavoro doveva essere terminato entro la fine della settimana.

La cameriera, obbedendo all’ordine del re, si mise subito al lavoro e pettinò il lino, arrotolandolo sul fuso e filandolo così diligentemente che il lavoro fu tutto fatto il sabato sera. Ma Renzolla, che era stata viziata e coccolata a casa della fata ed era completamente ignara del proprio mutamento di aspetto, gettò il lino fuori della finestra e disse: “Che cosa ha pensato il re, dandomi da fare questo lavoro? Se vuole camicie, gliele posso comprare. Non è come se mi avesse raccolta dalla strada, perché dovrebbe ricordarsi che gli ho portato in dote settemila ghinee d’oro, e che sono sua moglie e non la sua schiava. Deve essere impazzito per trattarmi così.”

Ciononostante, quando fu sabato sera e vide che la cameriera aveva svolto il compito, ebbe paura di essere punita per la propria pigrizia. Così corse al palazzo della fata e le confidò tutte le proprie pene. La fata l’abbracciò teneramente e le diede un sacco di lino filato affinché potesse mostrarlo al re e fargli vedere che buona lavoratrice fosse. Renzolla prese il sacco senza una parola di ringraziamento e ritornò a palazzo, lasciando la gentile fata assai indignata per la sua mancanza di gratitudine.

Quando il re vide il lino filato, diede a Renzolla e alla cameriera un cagnolino ciascuna e disse loro di accudire gli animali e di trattarli con cura.

La cameriera lo allevò con la più grande cura possibile e lo trattò come un figlio. Ma Renzolla disse: “Non so che cosa pensare. Che sia finita in mezzo a un branco di matti? Il re suppone che io possa pettinare e nutrire un cane con le mie mani?” Con queste parole aprì la finestra e gettò fuori la povera bestiola, che cadde sul pavimento morta e stecchita.

Quando che furono trascorsi pochi mesi il re mandò un messaggio, dicendo che gli sarebbe piaciuto vedere come stavano i cani. Renzolla, sentendosi in colpa per quella richiesta, corse un’altra volta dalla fata. Stavolta trovò un vecchio alla porta del palazzo della fata, il quale le disse: “Chi sei e che cosa vuoi?”

Sentendo la domanda, Renzolla rispose irosamente: “Non mi conosci, vecchia barba di capra? E come osi rivolgerti a me in questo modo?”

”Il bue che dice ‘cornuto’all’asino!” rispose il vecchio, “perché non sono io, ma tu, ad avere una testa di capra. Aspetta un momento, miserabile ingrata, e ti mostrerò dove ti ha condotta la mancanza di gratitudine.”

Con queste parole corse via e ritornò con uno specchio, che mise davanti a Renzolla. Alla vista della propria bruttezza, la ragazza quasi svenne per l’orrore e proruppe in alti lamenti nel vedere il proprio volto così cambiato.

Allora il vecchio disse: “Devi ricordare, Renzolla, che sei la figlia di un contadino e che la fata ha fatto di te una regina; ma sei stata ingrata, non l’hai mai ringraziata per tutto ciò che ha fatto per te. Perciò ha deciso di punirti. Ma se desideri perdere la tua lunga barba bianca, gettati ai piedi della fata e implorala che ti perdoni. Ha il cuore tenero e forse avrà pietà di te.”

Renzolla, che era veramente dispiaciuta per la propria condotta, ascoltò il consiglio del vecchio e la fata non solo le restituì il primitivo aspetto, ma la abbigliò con un abito ricamato d’oro, le offrì una meravigliosa carrozza e la rimandò indietro dal marito, accompagnata da una schiera di servitori. Quando il re vide che il suo aspetto era più bello che mai, si innamorò un’altra volta e si pentì amaramente di averle causato tante sofferenze.

Così Renzolla visse per sempre felice e contenta perché amava suo marito, rispettava la fata ed era grata al vecchio per averle detto la verità.

(1) essere minacciato contemporaneamente da due pericoli o malanni difficilmente evitabili, e in genere essere in una situazione grave o imbarazzante, in un brutto impiccio

(2) Moneta d’oro inglese emessa da Carlo II d’Inghilterra nel 1665 e così detta perché coniata con l’oro proveniente dalla costa della Guinea, del valore inizialmente oscillante dai 20 ai 30 scellini e poi stabilizzato (1717) a 21 scellini.

Tradotto dall’italiano da Herman Kletke

(N.d.T.) Questa è la versione inglese di una fiaba italiana contenuta ne Lo cunto de li cunti di Giambattista Basile, La faccia di capra che nel libro costituisce il trattenimento ottavo della giornata prima.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)