The One-handed Girl

(MP3-29'05'')

AN old couple once lived in a hut under a grove of palm trees, and they had one son and one daughter. They were all very happy together for many years, and then the father became very ill, and felt he was going to die. He called his children to the place where he lay on the floor—for no one had any beds in that country—and said to his son, 'I have no herds of cattle to leave you—only the few things there are in the house—for I am a poor man, as you know. But choose: will you have my blessing or my property?'

'Your property, certainly,' answered the son, and his father nodded.

'And you?' asked the old man of the girl, who stood by her brother.

'I will have blessing,' she answered, and her father gave her much blessing.

That night he died, and his wife and son and daughter mourned for him seven days, and gave him a burial according to the custom of his people. But hardly was the time of mourning over, than the mother was attacked by a disease which was common in that country.

'I am going away from you,' she said to her children, in a faint voice; 'but first, my son, choose which you will have: blessing or property.'

'Property, certainly,' answered the son,

'And you, my daughter?'

'I will have blessing,' said the girl; and her mother gave her much blessing, and that night she died.

When the days of mourning were ended, the brother bade his sister put outside the hut all that belonged to his father and his mother. So the girl put them out, and he took them away, save only a small pot and a vessel in which she could clean her corn. But she had no corn to clean.

She sat at home, sad and hungry, when a neighbour knocked at the door.

'My pot has cracked in the fire, lend me yours to cook my supper in, and I will give you a handful of corn in return.'

And the girl was glad, and that night she was able to have supper herself, and next day another woman borrowed her pot, and then another and another, for never were known so many accidents as befell the village pots at that time. She soon grew quite fat with all the corn she earned with the help of her pot, and then one evening she picked up a pumpkin seed in a corner, and planted it near her well, and it sprang up, and gave her many pumpkins.

At last it happened that a youth from her village passed through the place where the girl's brother was, and the two met and talked.

'What news is there of my sister?' asked the young man, with whom things had gone badly, for he was idle.

'She is fat and well-liking,' replied the youth, 'for the women borrow her mortar to clean their corn, and borrow her pot to cook it in, and for all this they give her more food than she can eat.' And he went his way.

Now the brother was filled with envy at the words of the man, and he set out at once, and before dawn he had reached the hut, and saw the pot and the mortar were standing outside. He slung them over his shoulders and departed, pleased with his own cleverness; but when his sister awoke and sought for the pot to cook her corn for breakfast, she could find it nowhere. At length she said to herself:

'Well, some thief must have stolen them while I slept. I will go and see if any of my pumpkins are ripe.' And indeed they were, and so many that the tree was almost broken by the weight of them. So she ate what she wanted and took the others, to the village, and gave them in exchange for corn, and the women said that no pumpkins were as sweet as these, and that she was to bring every day all that she had. In this way she earned more than she needed for herself, and soon was able to get another mortar and cooking pot in exchange for her corn. Then she thought she was quite rich.

Unluckily someone else thought so too, and this was her brother's wife, who had heard all about the pumpkin tree, and sent her slave with a handful of grain to buy her a pumpkin. At first the girl told him that so few were left that she could not spare any; but when she found that he belonged to her brother, she changed her mind, and went out to the tree and gathered the largest and the ripest that was there.

'Take this one,' she said to the slave, 'and carry it back to your mistress, but tell her to keep the corn, as the pumpkin is a gift.'

The brother's wife was overjoyed at the sight of the fruit, and when she tasted it, she declared it was the nicest she had ever eaten. Indeed, all night she thought of nothing else, and early in the morning she called another slave (for she was a rich woman) and bade him go and ask for another pumpkin. But the girl, who had just been out to look at her tree, told him that they were all eaten, so he went back empty-handed to his mistress.

In the evening her husband returned from hunting a long way off, and found his wife in tears.

'What is the matter?' asked he.

'I sent a slave with some grain to your sister to buy some pumpkins, but she would not sell me any, and told me there were none, though I know she lets other people buy them.'

'Well, never mind now—go to sleep,' said he, 'and to-morrow I will go and pull up the pumpkin tree, and that will punish her for treating you so badly.'

So before sunrise he got up and set out for his sister's house, and found her cleaning some corn.

'Why did you refuse to sell my wife a pumpkin yesterday when she wanted one?' he asked.

'The old ones are finished, and the new ones are not yet come,' answered the girl. 'When her slave arrived two days ago, there were only four left; but I gave him one, and would take no corn for it.'

'I do not believe you: you have sold them all to other people. I shall go and cut down the pumpkin,' cried her brother in a rage.

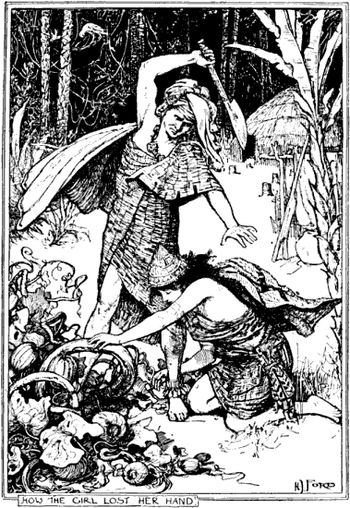

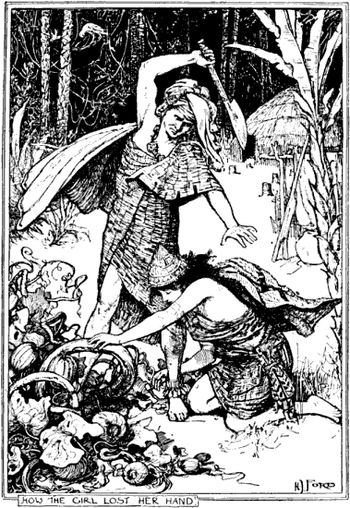

'If you cut down the pumpkin you shall cut off my hand with it,' exclaimed the girl, running up to her tree and catching hold of it. But her brother followed, and with one blow cut off the pumpkin and her hand too.

Then he went into the house and took away everything he could find, and sold the house to a friend of his who had long wished to have it, and his sister had no home to go to.

Meanwhile she had bathed her arm carefully, and bound on it some healing leaves that grew near by, and wrapped a cloth round the leaves, and went to hide in the forest, that her brother might not find her again.

For seven days she wandered about, eating only the fruit that hung from the trees above her, and every night she climbed up and tucked herself safely among the creepers which bound together the big branches, so that neither lions nor tigers nor panthers might get at her.

When she woke up on the seventh morning she saw from her perch smoke coming up from a little town on the edge of the forest. The sight of the huts made her feel more lonely and helpless than before. She longed desperately for a draught of milk from a gourd, for there were no streams in that part, and she was very thirsty, but how was she to earn anything with only one hand? And at this thought her courage failed, and she began to cry bitterly.

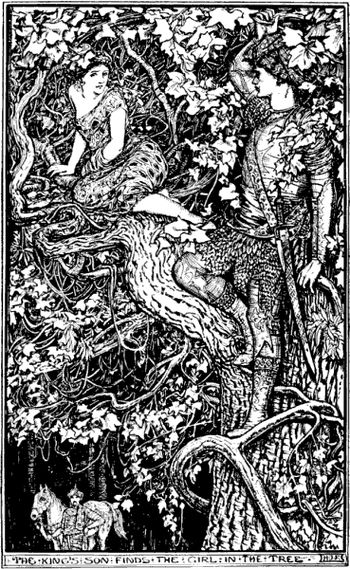

It happened that the king's son had come out from the town very early to shoot birds, and when the sun grew hot he felt tired.

'I will lie here and rest under this tree,' he said to his attendants. 'You can go and shoot instead, and I will just have this slave to stay with me!' Away they went, and the young man fell asleep, and slept long. Suddenly he was awakened by something wet and salt falling on his face.

'What is that? Is it raining?' he said to his slave. 'Go and look.'

'No, master, it is not raining,' answered the slave.

'Then climb up the tree and see what it is,' and the slave climbed up, and came back and told his master that a beautiful girl was sitting up there, and that it must have been her tears which had fallen on the face of the king's son.

'Why was she crying?' inquired the prince.

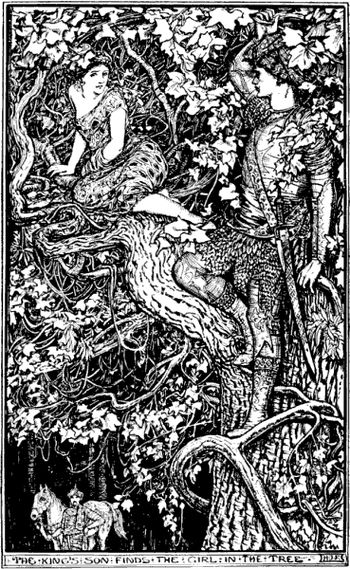

'I cannot tell—I did not dare to ask her; but perhaps she would tell you.' And the master, greatly wondering, climbed up the tree.

'What is the matter with you?' said he gently, and, as she only sobbed louder, he continued:

'Are you a woman, or a spirit of the woods?'

'I am a woman,' she answered slowly, wiping her eyes with a leaf of the creeper that hung about her.

'Then why do you cry?' he persisted.

'I have many things to cry for,' she replied, 'more than you could ever guess.'

'Come home with me,' said the prince; 'it is not very far. Come home to my father and mother. I am a king's son.'

'Then why are you here?' she said, opening her eyes and staring at him.

'Once every month I and my friends shoot birds in the forest,' he answered, 'but I was tired and bade them leave me to rest. And you—what are you doing up in this tree?'

At that she began to cry again, and told the king's son all that had befallen her since the death of her mother.

'I cannot come down with you, for I do not like anyone to see me,' she ended with a sob.

'Oh! I will manage all that,' said the king's son, and swinging himself to a lower branch, he bade his slave go quickly into the town, and bring back with him four strong men and a curtained li tter. When the man was gone, the girl climbed down, and hid herself on the ground in some bushes. Very soon the slave returned with the litter, which was placed on the ground close to the bushes where the girl lay.

'Now go, all of you, and call my attendants, for I do not wish to stay here any longer,' he said to the men, and as soon as they were out of sight he bade the girl get into the litter, and fasten the curtains tightly. Then he got in on the other side, and waited till his attendants came up.

'What is the matter, O son of a king?' asked they, breathless with running.

'I think I am ill; I am cold,' he said, and signing to the bearers, he drew the curtains, and was carried through the forest right inside his own house.

'Tell my father and mother that I have a fever, and want some gruel,' said he, 'and bid them send it quickly.'

So the slave hastened to the king's palace and gave his message, which troubled both the king and the queen greatly. A pot of hot gruel was instantly prepared, and carried over to the sick man, and as soon as the council which was sitting was over, the king and his ministers went to pay him a visit, bearing a message from the queen that she would follow a little later.

Now the prince had pretended to be ill in order to soften his parents' hearts, and the next day he declared he felt better, and, getting into his litter, was carried to the palace in state, drums being beaten all along the road.

He dismounted at the foot of the steps and walked up, a great parasol being held over his head by a slave. Then he entered the cool, dark room where his father and mother were sitting, and said to them:

'I saw a girl yesterday in the forest whom I wish to marry, and, unknown to my attendants, I brought her back to my house in a litter. Give me your consent, I beg, for no other woman pleases me as well, even though she has but one hand!'

Of course the king and queen would have preferred a daughter-in-law with two hands, and one who could have brought riches with her, but they could not bear to say 'No' to their son, so they told him it should be as he chose, and that the wedding feast should be prepared immediately.

The girl could scarcely believe her good fortune, and, in gratitude for all the kindness shown her, was so useful and pleasant to her husband's parents that they soon loved her.

By and bye a baby was born to her, and soon after that the prince was sent on a journey by his father to visit some of the distant towns of the kingdom, and to set right things that had gone wrong.

No sooner had he started than the girl's brother, who had wasted all the riches his wife had brought him in recklessness and folly, and was now very poor, chanced to come into the town, and as he passed he heard a man say, 'Do you know that the king's son has married a woman who has lost one of her hands?' On hearing these words the brother stopped and asked, 'Where did he find such a woman?'

'In the forest,' answered the man, and the cruel brother guessed at once it must be his sister.

A great rage took possession of his soul as he thought of the girl whom he had tried to ruin being after all so much better off than himself, and he vowed that he would work her ill. Therefore that very afternoon he made his way to the palace and asked to see the king.

When he was admitted to his presence, he knelt down and touched the ground with his forehead, and the king bade him stand up and tell wherefore he had come.

'By the kindness of your heart have you been deceived, O king,' said he. 'Your son has married a girl who has lost a hand. Do you know why she has lost it? She was a witch, and has wedded three husbands, and each husband she has put to death with her arts. Then the people of the town cut off her hand, and turned her into the forest. And what I say is true, for her town is my town also.'

The king listened, and his face grew dark. Unluckily he had a hasty temper, and did not stop to reason, and, instead of sending to the town, and discovering people who knew his daughter-in-law and could have told him how hard she had worked and how poor she had been, he believed all the brother's lying words, and made the queen believe them too. Together they took counsel what they should do, and in the end they decided that they also would put her out of the town. But this did not content the brother.

'Kill her,' he said. 'It is no more than she deserves for daring to marry the king's son. Then she can do no more hurt to anyone.'

'We cannot kill her,' answered they; 'if we did, our son would assuredly kill us. Let us do as the others did, and put her out of the town.' And with this the envious brother was forced to be content.

The poor girl loved her husband very much, but just then the baby was more to her than all else in the world, and as long as she had him with her, she did not very much mind anything. So, taking her son on her arm, and hanging a little earthen pot for cooking round her neck, she left her house with its great peacock fans and slaves and seats of ivory, and plunged into the forest.

For a while she walked, not knowing whither she went, then by and bye she grew tired, and sat under a tree to rest and to hush her baby to sleep. Suddenly she raised her eyes, and saw a snake wriggling from under the bushes towards her.

'I am a dead woman,' she said to herself, and stayed quite still, for indeed she was too frightened to move. In another minute the snake had reached her side, and to her surprise he spoke.

'Open your earthen pot, and let me go in. Save me from sun, and I will save you from rain,' and she opened the pot, and when the snake had slipped in, she put on the cover. Soon she beheld another snake coming after the other one, and when it had reached her it stopped and said, 'Did you see a small grey snake pass this way just now?'

'Yes,' she answered, 'it was going very quickly.'

'Ah, I must hurry and catch it up,' replied the second snake, and it hastened on.

When it was out of sight, a voice from the pot said:

'Uncover me,' and she lifted the lid, and the little grey snake slid rapidly to the ground.

'I am safe now,' he said. 'But tell me, where are you going?'

'I cannot tell you, for I do not know,' she answered. 'I am just wandering in the wood.'

'Follow me, and let us go home together,' said the snake, and the girl followed him through the forest and along the green paths, till they came to a great lake, where they stopped to rest.

The sun is hot,' said the snake, 'and you have walked far. Take your baby and bathe in that cool place where the boughs of the tree stretch far over the water.'

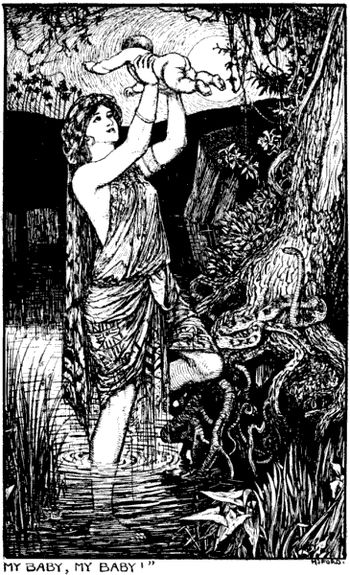

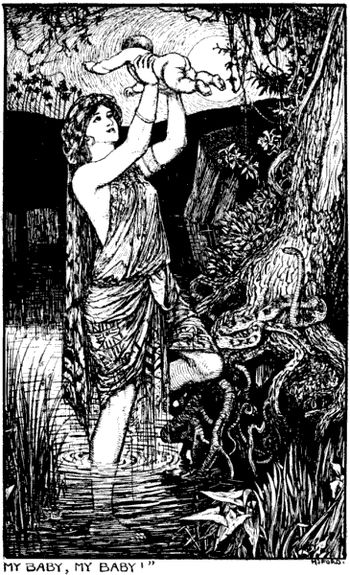

'Yes, I will,' answered she, and they went in. The baby splashed and crowed with delight, and then he gave a spring and fell right in, down, down, down, and his mother could not find him, though she searched all among the reeds.

Full of terror, she made her way back to the bank, and called to the snake, 'My baby is gone!—he is drowned, and never shall I see him again.'

'Go in once more,' said the snake, 'and feel everywhere, even among the trees that have their roots in the water, lest perhaps he may be held fast there.'

Swiftly she went back and felt everywhere with her whole hand, even putting her fingers into the tiniest crannies, where a crab could hardly have taken shelter.

'No, he is not here,' she cried. 'How am I to live without him?' But the snake took no notice, and only answered, 'Put in your other arm too.'

'What is the use of that?' she asked, 'when it has no hand to feel with?' but all the same she did as she was bid, and in an instant the wounded arm touched something round and soft, lying between two stones in a clump of reeds.

'My baby, my baby!' she shouted, and lifted him up, merry and laughing, and not a bit hurt or frightened.

'Have you found him this time?' asked the snake.

'Yes, oh, yes!' she answered, 'and, why—why—I have got my hand back again!' and from sheer joy she burst into tears.

The snake let her weep for a little while, and then he said—

'Now we will journey on to my family, and we will all repay you for the kindness you showed to me.' '

You have done more than enough in giving me[ back my hand,' replied the girl; but the snake only smiled.

'Be quick, lest the sun should set,' he answered, and began to wriggle along so fast that the girl could hardly follow him.

By and bye they arrived at the house in a tree where the snake lived, when he was not travelling with his father and mother. And he told them all his adventures, and how he had escaped from his enemy. The father and mother snake could not do enough to show their gratitude. They made their guest lie down on a hammock woven of the strong creepers which hung from bough to bough, till she was quite rested after her wanderings, while they watched the baby and gave him milk to drink from the coconuts which they persuaded their friends the monkeys to crack for them. They even managed to carry small fruit tied up in their tails for the baby's mother, who felt at last that she was safe and at peace. Not that she forgot her husband, for she often thought of him and longed to show him her son, and in the night she would sometimes lie awake and wonder where he was.

In this manner many weeks passed by.

And what was the prince doing?

Well, he had fallen very ill when he was on the furthest border of the kingdom, and he was nursed by some kind people who did not know who he was, so that the king and queen heard nothing about him. When he was better he made his way slowly home again, and into his father's palace, where he found a strange man standing behind the throne with the peacock's feathers. This was his wife's brother, whom the king had taken into high favour, though, of course, the prince was quite ignorant of what had happened.

For a moment the king and queen stared at their son, as if he had been unknown to them; he had grown so thin and weak during his illness that his shoulders were bowed like those of an old man.

'Have you forgotten me so soon?' he asked.

At the sound of his voice they gave a cry and ran towards him, and poured out questions as to what had happened, and why he looked like that. But the prince did not answer any of them.

'How is my wife?' he said. There was a pause.

Then the queen replied:

'She is dead.'

'Dead!' he repeated, stepping a little backwards. 'And my child?'

'He is dead too.'

The young man stood silent. Then he said, 'Show me their graves.'

At these words the king, who had been feeling rather uncomfortable, took heart again, for had he not prepared two beautiful tombs for his son to see, so that he might never, never guess what had been done to his wife? All these months the king and queen had been telling each other how good and merciful they had been not to take her brother's advice and to put her to death. But now, this somehow did not seem so certain.

Then the king led the way to the courtyard just behind the palace, and through the gate into a beautiful garden where stood two splendid tombs in a green space under the trees. The prince advanced alone, and, resting his head against the stone, he burst into tears. His father and mother stood silently behind with a curious pang in their souls which they did not quite understand. Could it be that they were ashamed of themselves?

But after a while the prince turned round, and walking past them into the palace he bade the slaves bring him mourning. For seven days no one saw him, but at the end of them he went out hunting, and helped his[Pg 204] father rule his people as before. Only no one dared to speak to him of his wife and son.

At last one morning, after the girl had been lying awake all night thinking of her husband, she said to her friend the snake:

'You have all shown me much kindness, but now I am well again, and want to go home and hear some news[ of my husband, and if he still mourns for me!' Now the heart of the snake was sad at her words, but he only said:

'Yes, thus it must be; go and bid farewell to my father and mother, but if they offer you a present, see that you take nothing but my father's ring and my mother's casket.'

So she went to the parent snakes, who wept bitterly at the thought of losing her, and offered her gold and jewels as much as she could carry in remembrance of them. But the girl shook her head and pushed the shining heap away from her.

'I shall never forget you, never,' she said in a broken voice, 'but the only tokens I will accept from you are that little ring and this old casket.'

The two snakes looked at each other in dismay. The ring and the casket were the only things they did not want her to have. Then after a short pause they spoke.

'Why do you want the ring and casket so much? Who has told you of them?'

'Oh, nobody; it is just my fancy,' answered she. But the old snakes shook their heads and replied: 'Not so; it is our son who told you, and, as he said, so it must be. If you need food, or clothes, or a house, tell the ring and it will find them for you. And if you are unhappy or in danger, tell the casket and it will set things right.' Then they both gave her their blessing, and she picked up her baby and went her way.

She walked for a long time, till at length she came near the town where her husband and his father dwelt. Here she stopped under a grove of palm trees, and told the ring that she wanted a house.

'It is ready, mistress,' whispered a queer little voice which made her jump, and, looking behind her, she saw a lovely palace made of the finest woods, and a row of slaves with tall fans bowing before the door. Glad indeed was she to enter, for she was very tired, and, after eating a good supper of fruit and milk which she found in one of the rooms, she flung herself down on a pile of cushions and went to sleep with her baby beside her.

Here she stayed quietly, and every day the baby grew taller and stronger, and very soon he could run about and even talk. Of course the neighbours had a great deal to say about the house which had been built so quickly—so very quickly—on the outskirts of the town, and invented all kinds of stories about the rich lady who lived in it. And by and bye, when the king returned with his son from the wars, some of these tales reached his ears.

'It is really very odd about that house under the palms,' he said to the queen; 'I must find out something of the lady whom no one ever sees. I daresay it is not a lady at all, but a gang of conspirators who want to get possession of my throne. To-morrow I shall take my son and my chief ministers and insist on getting inside.'

Soon after sunrise next day the prince's wife was standing on a little hill behind the house, when she saw a cloud of dust coming through the town. A moment afterwards she heard faintly the roll of the drums that announced the king's presence, and saw a crowd of people approaching the grove of palms. Her heart beat fast. Could her husband be among them? In any case they must not discover her there; so just bidding the ring prepare some food for them, she ran inside, and bound a veil of golden gauze round her head and face. Then, taking the child's hand, she went to the door and waited.

In a few minutes the whole procession came up, and she stepped forward and begged them to come in and rest.

'Willingly,' answered the king; 'go first, and we will follow you.'

They followed her into a long dark room, in which[Pg 207] was a table covered with gold cups and baskets filled with dates and coconuts and all kinds of ripe yellow fruits, and the king and the prince sat upon cushions and were served by slaves, while the ministers, among whom she recognised her own brother, stood behind.

'Ah, I owe all my misery to him,' she said to herself. 'From the first he has hated me,' but outwardly she showed nothing. And when the king asked her what news there was in the town she only answered:

'You have ridden far; eat first, and drink, for you must be hungry and thirsty, and then I will tell you my news.'

'You speak sense,' answered the king, and silence prevailed for some time longer. Then he said:

'Now, lady, I have finished, and am refreshed, therefore tell me, I pray you, who you are, and whence you come? But, first, be seated.'

She bowed her head and sat down on a big scarlet cushion, drawing her little boy, who was asleep in a corner, on to her knee, and began to tell the story of her life. As her brother listened, he would fain have left the house and hidden himself in the forest, but it was his duty to wave the fan of peacock's feathers over the king's head to keep off the flies, and he knew he would be seized by the royal guards if he tried to desert his post. He must stay where he was, there was no help for it, and luckily for him the king was too much interested in the tale to notice that the fan had ceased moving, and that flies were dancing right on the top of his thick curly hair.

The story went on, but the story-teller never once looked at the prince, even through her veil, though he on his side never moved his eyes from her.

When she reached the part where she had sat weeping in the tree, the king's son could restrain himself no longer.

'It is my wife,' he cried, springing to where she sat with the sleeping child in her lap. 'They have lied to me, and you are not dead after all, nor the boy either! But what has happened? Why did they lie to me? and why did you leave my house where you were safe?' And he turned and looked fiercely at his father.

'Let me finish my tale first, and then you will know,' answered she, throwing back her veil, and she told how her brother had come to the palace and accused her of being a witch, and had tried to persuade the king to slay her. 'But he would not do that,' she continued softly, 'and after all, if I had stayed on in your house, I should never have met the snake, nor have got my hand back again. So let us forget all about it, and be happy once more, for see! our son is growing quite a big boy.'

'And what shall be done to your brother?' asked the king, who was glad to think that someone had acted in this matter worse than himself.

'Put him out of the town,' answered she.

From 'Swaheli Tales,' by E. Steere

La ragazza con una mano sola

C’era una volta un’anziana coppia che viveva in un capanno sotto un boschetto di palme e che aveva un figlio e una figlia. Furono felici insieme per molti anni, poi il padre si ammalò e capì di essere in punto di morte. Chiamò i figli presso il giaciglio sul pavimento, perché nessuno in quel paese aveva letti, e disse al figlio: “Non ho mandrie di bestiame da lasciarti, ma solo le poche cose che si trovano in questa casa perché sono un uomo povero, lo sai. Però scegli: vuoi avere o la mia benedizione o i miei beni?

”I tuoi beni, certamente.” rispose il figlio, e il padre annuì.

”E tu?” chiese il vecchio alla ragazza, che stava accanto al fratello.

”Voglio la tua benedizione.” rispose, e il padre le diede ogni benedizione.

Quella notte morì e sua moglie, il figlio e la figlia lo piansero per sette giorni poi gli diedero sepoltura secondo le usanze del loro popolo. Ma era appena finito il periodo di lutto che la madre contrasse una malattia diffusa in quel paese.

”Sto per lasciarvi,” disse ai figli con voce flebile, “,a prima, figlio mio, scegli che cosa vuoi avere: la benedizione o i beni.”

”I beni, certamente.” rispose il figlio.

”E tu, figlia mia?”

”Io voglio avere la benedizione.” disse la ragazza; la madre le diede ogni benedizione e quella notte morì.

Quando furono terminate I giorni del lutto, il fratello ordinò alla sorella di mettere fuori dal capanno tutto i beni che apparteneva al padre e alla madre. Così la ragazza li mise fuori e lui li portò via, tranne una piccola pentola e un mortaio nel quale avrebbe potuto macinare il grano, ma non aveva grano da macinare.

Sedeva in casa, triste e affamata, quando una vicina bussò alla porta.

”La mia pentola si è incrinata sul fuoco, lasciami cucinare la cena nella tua e in cambio ti darò una manciata di grano.”

La ragazza ne fu contenta, quella sera avrebbe potuto cenare anche lei, e il giorno seguente un’altra donna prese in prestito la sua pentola, e poi un’altra e un’altra, perché nessuno sapeva che accidenti fosse accaduto a tutte le pentole del villaggio nel medesimo tempo. Ben presto ingrassò con tutto il grano ricavato con l’aiuto della pentola; una sera raccolse un seme di zucca in un angolo e lo piantò vicino al muro, crebbe e le fruttò molte zucche.

Infine accadde che un giovane del suo villaggio passasse nel luogo in cui si trovava il fratello della ragazza e i due si incontrarono e chiacchierarono.

”Che notizie ci sono di mia sorella?” chiese il giovane, al quale le cose erano andate male perché era disoccupato.

”È grassa e ben messa,” rispose l’altro giovane, “perché le donne prendono in prestito il suo mortaio per macinare il grano e la sua pentola per cucinarlo, perciò le danno molto più cibo di quanto possa mangiarne.” E se ne andò per la sua strada.

Il fratello divenne molto invidioso nel sentire le parole dell’uomo e partì subito, raggiungendo il capanno prima di sera; vide che la pentola e il mortaio erano lì fuori. Se li mise in spalla e ripartì, contento della propria astuzia; quando la sorella si svegliò e cercò la pentola per cucinare il grano per la colazione, non poté trovarla da nessuna parte. Alla fine si disse:

’Un ladro deve averla rubata mentre dormivo. Andrò a vedere se qualcuna delle mie zucche è matura.’ E infatti lo erano, così tante che la pianta quasi si spezzava sotto il loro peso. Così mangiò quanto voleva e portò le altre al villaggio, dove le diede in cambio del grano e le donne dissero che nessuna zucca era dolce come quelle e che doveva portare ogni giorno tutte quelle che aveva. In questo modo guadagnò di quanto le servisse e ben presto fu in grado di avere in cambio un altro mortaio e un’altra pentola per cucinare il grano. Allora pensò di essere quasi ricca.

Sfortunatamente lo pensava anche qualcun altro, e questa era la moglie di suo fratello, che aveva sentito tutto sulla pianta di zucche e aveva mandato il suo schiavo a comperare una zucca in cambio di una manciata di grano. Dapprima la ragazza gli disse che ne erano rimaste così poche che non poteva fare a meno di nessuna, ma quando scoprì che lo schiavo apparteneva al fratello, cambiò idea e andò all’albero a cogliere la più grossa e la più matura che ci fosse.

”Prendi questa,” disse allo schiavo, “e portala alla tua padrona, ma dille di tenere il grano perché la zucca è un regalo.”

La moglie del fratello fu felicissima alla vista del frutto e, quando lo assaggiò, dichiarò che era il più buono che avesse mai mangiato. In effetti non pensò a nient’altro per tutta la notte e il mattino seguente di buon’ora chiamò un altro schiavo (perché era una donna ricca) e gli ordinò di andare a chiedere un’altra zucca. Ma la ragazza, che aveva appena dato un’occhiata alla pianta, gli disse che le avevano mangiate tutte, così egli tornò dalla padrona a mani vuote.

Quella sera il marito ritornò dopo essere stato a caccia assai lontano e trovò la moglie in lacrime.

”Che succede?” le chiese.

”Ho mandato uno schiavo da tua sorella con un po’ di grano per acquistare alcune zucche, ma lei non ha voluto vendermele e mi ha detto di non averne, sebbene io sappia che le ha fatte acquistare ad altre persone.”

”Non ti preoccupare, vai a dormire,” disse lui, “e domani andrò a sradicare la pianta di zucche e questa sarà la sua punizione per averti trattata così male.”

Così prima del sorgere del sole si alzò e andò a casa della sorella; la trovò che macinava il grano.

”Perché ieri ti sei rifiutata di vendere una zucca a mia moglie quando la voleva?” le chiese.

”Quelle vecchie erano finite e quelle nuove non sono ancora pronte.” Rispose la ragazza. “Quando il suo schiavo e venuto due giorni fa, ne erano rimaste solo quattro; ma io gliene ho data una e non ho preso in cambio il grano.”

”Non ti credo; le hai vendute ad altre persone. Andrò a tagliare la pianta delle zucche.” strillò rabbioso il fratello.

”Se tagli la pianta di zucche, dovrai tagliare con esso anche la mia mano.” Esclamò la ragazza, correndo verso la pianta e afferrandola. Ma il fratello la seguì e con un colpo tagliò la pianta e anche la sua mano.

Poi entrò in casa e portò via tutto ciò che poté trovare, e vendette la casa a un amico che da tempo desiderava averla, così sua sorella non ebbe una casa in cui stare.

Intanto lei aveva pulito con cura il braccio e lo aveva fasciato con alcune foglie medicamentose che crescevano lì vicino, poi avvolse un panno intorno alle foglie e andò a nascondersi nella foresta così che il fratello non potesse ritrovarla.

Vagò per sette giorni, cibandosi solo dei frutti degli alberi, e ogni notte si arrampicava e si sistemava al sicuro tra i rampicati che s’intrecciavano ai grossi rami, così che i leoni e le pantere non potessero raggiungerla.

Quando si svegliò la mattina del settimo giorno dal proprio rifugio vide il fumo che proveniva da una piccola città ai margini della foresta. La vista delle capanne la fece sentire ancora più sola e indifesa di prima. Desiderava disperatamente un sorso di latte in un recipiente ricavato da una zucca, perché non c’erano fiumi in quella zona, e lei era molto assetata, ma come avrebbe potuto fare qualcosa con una mano sola? E a questo pensiero il suo coraggio svanì e cominciò a piangere amaramente.

Capitò che il figlio del re fosse uscito assai presto dalla città a caccia di uccelli e, quando il sole fu alto, si sentì stanco.

”Mi sdraierò qui e riposerò sotto quest’albero.” disse agli attendenti. “Voi invece andate a caccia e io farò restare con me solo questo schiavo.” Questi se ne andarono e il giovane si addormentò e dormì a lungo. Improvvisamente fu svegliato qualcosa di bagnato e di salato sul viso.

”Che cosa c’è? Sta piovendo?” chiese allo schiavo. “Andiamo a vedere.”

”No, padrone, non sta piovendo.” rispose lo schiavo.

”Allora arrampicati sull’albero e guarda di che cosa si tratta. Lo schiavo si arrampicò e tornò indietro dicendo al padrone che una splendida ragazza era seduta là in cima e che dovevano essere state le sue lacrime a cadere sul volto del figlio del re.

”Perché sta piangendo?” chiese in principe.

”Non ve lo so dire, e non ho osato domandarglielo; ma forse lo direbbe a voi.” E il principe, assai meravigliato, si arrampicò sull’albero.

”Che cosa ti succede?” disse gentilmente e, siccome singhiozzava soltanto, continuò:

”Sei una donna o uno spirito dei boschi?”

”Sono una donna.” rispose lentamente, asciugandosi gli occhi con una foglia dei rampicanti che la circondavano.

”Allora perché piangi?” insistette il principe.

”Ho molti motivi per piangere,” rispose la ragazza, “più di quanti tu possa mai indovinare.”

”Vieni a casa con me,” disse il principe, “non è molto lontana. A casa da mio padre e da mia madre. Io sono il figlio di un re.”

”Allora come mai sei qui?” chiese la ragazza, aprendo gli occhi e fissandolo.

”Una volta al mese io e I miei amici Andiamo a caccia di uccelli nella foresta,” rispose il principe, “ma mi ero stancato e ho detto loro di lasciarmi riposare. E tu, che stai facendo su quest’albero?”

A queste parole la ragazza ricominciò a piangere e raccontò al figlio del re tutto ciò che le era accaduto dalla morte della madre.

”Io non posso scendere con te perché non voglio che nessuno mi veda.” concluse con un singhiozzo.

”Penserò a tutto io.” disse il figlio del re e, appendendosi a un ramo più basso, ordinò allo schiavo di andare rapidamente in città e di riportare con sé quattro uomini forti e una portantina con le tende. Quando l’uomo se ne fu andato, la ragazza scese e si nascose a terra tra alcuni cespugli. Lo schiavo ritornò assai presto con la portantina, che fu posata sul terreno vicino ai cespugli in cui si nascondeva la ragazza.

”Adesso andate tutti e chiamate i miei attendenti perché non desidero stare qui più a lungo.” disse il principe agli uomini ,e appena furono spariti alla sua vista, disse alla ragazza di entrare nella portantina e chiuse ben bene le tende. Poi entrò dall’altra parte e attese finché giunsero gli attendenti.

”Che succede, figlio di re?” domandarono essi, con il fiato corto per la corsa.

”Penso di essere malato, ho freddo,” disse, e, facendo segno ai portatori, tirò le tende e fu trasportato attraverso la foresta dritto a casa.

”Di’ a mio padre e a mia madre che ho la febbre e voglio un po’ di farinata,” disse, “ e che me la mandino in fretta.”

Così lo schiavo si affrettò verso il palazzo del re e portò il messaggio, che preoccupò grandemente il re e la regina. Fu subito preparata una scodella di farinata e portata al malato, e appena fu terminato il consiglio che si era riunito, il re e i suoi ministri andarono a fargli visita, portando un messaggio da parte della regina, che sarebbe venuta un po’ più tardi.

Dovete sapere che il principe fingeva di essere malato per ammorbidire il cuore dei genitori e il giorno seguente dichiarò di sentirsi meglio e, condotto nella portantina, fu trasportato al palazzo in pompa magna, con i tamburi che rullavano lungo tutta la strada.

Scese ai piedi delle scale e salì, con un grande parasole sorretto sulla sua testa da uno schiavo. Poi entrò nella vasta e fredda sala in cui erano seduti il padre e la madre e disse loro:

”Ieri nella foresta ho visto una ragazza che vorrei sposare e, di nascosto dai miei attendenti, l’ho portata a casa mia con una portantina. Datemi il vostro consenso, vi prego, perché nessuna donna mi piace come lei, sebbene abbia una mano sola.”

Naturalmente il re e la regina avrebbero preferito una nuora con due mani e che portasse una ricca dote, ma non se la sentirono di dire “no” a loro figlio, così gli dissero di fare come voleva e che la festa di nozze sarebbe stata organizzata immediatamente.

La ragazza non riusciva a credere alla propria fortuna e, grata per tutte le cortesie usatele, era così servizievole e garbata con i genitori del marito che ben presto l’amarono.

Di lì a poco le nacque un bambino e poco dopo il principe fu mandato in viaggio dal padre per visitare alcune lontane città del regno per sistemare faccende che si erano messe male.

Il principe era partito da poco che il fratello della ragazza, che aveva dilapidato in speculazioni e follie tutte le ricchezze che la moglie gli aveva portato, e adesso era di nuovo povero, decise di venire in città e, mentre passava, udì un uomo dire: “Sapete che il figlio del re ha sposato una donna che ha perso una mano?” Sentendo queste parole, si fermò e chiese: “E dove ha trovato una donna simile?”

”Nella foresta.” rispose l’uomo, e il crudele fratello intuì che doveva trattarsi di sua sorella.

Lo invase una grande collera, al pensiero che la ragazza che aveva portato alla rovina dopotutto stesse meglio di lui e giurò che le avrebbe fatto del male. Perciò quel pomeriggio stesso si recò al palazzo e chiese di vedere il re.

Quando fu ammesso alla sua presenza, s’inginocchiò e toccò il pavimento con la fronte; il re gli disse di alzarsi e di alzarsi e di dirgli per quale ragione fosse venuto.

”Per la bontà del vostro cuore siete stato ingannato, o re.” disse. “Vostro figlio ha sposato una ragazza con una mano sola. Sapete perché l’ha perduta? Era una strega, ha avuto tre mariti è ognuno di loro è morto per i suoi malefici. Allora la gente del posto le ha tagliato una mano e l’ha portata nella foresta. Ciò che dico è vero perché la sua città è anche la mia.”

Il re ascolto e si fece scuro in volto. Sfortunatamente aveva un carattere irruente e non sentiva ragioni così invece di mandare in città a scovare chi conoscesse sua nuora e potesse dirgli quanto aveva lavorato duramente e quanto fosse stata povera, credette a tutte le false parole del fratello e fece in modo che ci credesse anche la regina. Si consigliarono a vicenda sul da farsi e infine decisero che dovevano cacciarla dalla città. Ma ciò non bastò al fratello.

”Uccidetela,” disse “è ciò che merita per aver osato sposare il figlio del re. poi non potrà più danneggiare nessuno.”

”Non possiamo ucciderla,” risposero, “se lo facessimo, di sicuro nostro figlio ucciderebbe noi. Lasciamo che lo facciano altri e mandiamola via dalla città.” E con ciò il fratello invidioso fu costretto ad accontentarsi.

La povera ragazza amava moltissimo il marito, ma il bambino era tutto per lei al mondo e quando lo aveva con sé, non si preoccupava di nulla. così, prendendo in braccio il bambino e mettendosi al collo una piccola pentola di terracotta per cucinare, lasciò la casa con i suoi grandi ventagli di penne di pavone, gli schiavi e i sedili d’avorio e si inoltrò nella foresta.

Camminò per un po’, senza sapere dove andasse, e siccome dopo un po’ fu stanca, sedette sotto un albero a calmare il bambino per farlo addormentare. Improvvisamente alzò gli occhi e vide un serpente che strisciava verso di lei da sotto un cespuglio.

’Sono una donna morta.’ Si disse e rimase immobile perché davvero aveva troppa paura per muoversi. Un istante e poi il serpente fu al suo fianco, ma con sua sorpresa, parlò:

”Apri la tua pentola di terracotta e fammici entrare. Salvami dal sole e io ti salverò dalla pioggia.” La ragazza aprì la pentola e, quando il serpente vi fu scivolato dentro, chiuse il coperchio. Presto vide un altro serpente venire dopo l’altro e quando l’ebbe raggiunta, si fermò e disse. “Hai visto un piccolo serpente grigio passare da queste parti proprio adesso?”

La ragazza rispose: “Sì, stava andando molto in fretta.”

”Devo sbrigarmi e catturarlo.” Ribatté il secondo serpente e se ne andò rapido.

Quando fu sparito alla vista, una voce dalla pentola disse:

”Scoprimi.” La ragazza sollevò il coperchio e il serpentello grigio sgusciò rapidamente sul terreno.

”Adesso sono salvo.” Disse. “Ma dimmi, dove stai andando?”

”Non posso dirtelo perché non lo so.” rispose la ragazza. “Sto solo vagando per il bosco.”

”Seguimi e andiamo a casa insieme.” Disse il serpente, e la ragazza lo seguì attraverso la foresta e lungo i sentieri verdeggianti, finché giunsero a un grande lago, presso il quale si fermarono a riposare.

”Il sole è caldo,” disse il serpente, “ e tu hai camminato molto. prendi il bambino e bagnalo in quella pozza fresca dove i rami degli alberi si tendono sull’acqua.”

”Lo farò.” Rispose la ragazza e s’incamminò. Il bambino schizzava e lanciava gridolini di gioia, poi fece un balzo e cadde giù, giù, giù e sua madre non riusciva a trovarlo, sebbene lo cercasse tra le canne.

Terrorizzata, tornò indietro e chiamò il serpente. “Il mio bambino è sparito! È annegato, e non lo rivedrò mai più.”

”Torna di nuovo là,” disse il serpente, “e cerca dappertutto, persino tra gli alberi che affondano le radici nell’acqua, potrebbe darsi che sia intrappolato lì.”

La ragazza tornò indietro in fretta e cercò dappertutto con l’unica mano, persino infilando le dita nelle più piccole fessure, dove a malapena un granchio sarebbe potuto trovare rifugio.

”No, qui non c’è,” gridò, “Come potrò vivere senza di lui?” il serpente fece finta di nulla e rispose solo: “Infila dentro anche l’altro braccio.”

”A che scopo?” chiese la ragazza, “quando non ho una mano con cui toccare?” tuttavia fece come le era stato detto e all’istante il suo braccio mutilato toccò qualcosa di tondo e morbido, che giaceva tra due pietre in un gruppo di canne.

”Il mio bambino, il mio bambino!” gridò, e lo sollevò, che rideva felice, senza segni di ferite o di paura.

”Stavolta l’hai trovato?” chiese il serpente.

”Sì, oh, sì!” rispose la ragazza “ e, guarda, guarda! Ho di nuovo la mia mano!” E scoppiò in lacrime per la gioia assoluta.

Il serpente la lasciò piangere per un po’ poi disse:

”Adesso raggiungeremo la mia famiglia e ti ripagheremo tutti per la gentilezza che mi hai mostrato.”

”Hai fatto più che abbastanza nel restituirmi la mano.” rispose la ragazza, ma il serpente si limitò a sorridere.

”Affrettiamoci, prima che il sole tramonti.” disse il serpente e cominciò a strisciare così veloce che la ragazza riusciva a seguirlo a malapena.

Di lì a poco giunsero alla casa in un albero in cui viveva il serpente, quando non viaggiava con il padre e la madre. Raccontò loro le proprie avventure e come fosse sfuggito al nemico. Il padre e la madre facevano di tutto per mostrare la loro gratitudine. Fecero sdraiare l’ospite su un’amaca, intrecciata con i più robusti rampicanti, che era appesa da un ramo all’altro, finché la ragazza si fu ripresa a sufficienza dal cammino, mentre loro sorvegliavano il bambino e gli davano da bere latte delle noci di cocco che avevano convinto le amiche scimmie a rompere per loro. Poi riuscirono a portare piccoli frutti appesi alle code per la madre del bambino, che capì alla fine di essere in salvo e tranquilla. Non che avesse dimenticato il marito, perché pensava spesso a lui e desiderava mostrargli il bambino; a volte di notte giaceva sveglia e si chiedeva dove fosse.

In questo modo le settimane passarono.

E che ne era stato del principe?

Ebbene, era caduto molto malato mentre si trovava ai più lontani confini del regno ed era stato curato da un popolo gentile che non sapeva chi egli fosse, così il re e la regina non avevano saputo nulla di lui. Quando si sentì meglio, riprese di nuovo lentamente la via di casa e del palazzo di suo padre, in cui trovò uno strano uomo che stava dietro il trono con le piume di pavone. Era il fratello di sua moglie, che il re teneva in grande considerazione, benché naturalmente il principe ignorasse ciò che era accaduto.

Per un istante il re e la regina fissarono il figlio come se non sapessero chi fosse; era diventato così magro e debole durante la malattia che aveva le spalle cadenti come quelle di un vecchio.

”Mi avete già dimenticato?” chiese il principe.

Al suono della sua voce scoppiarono in lacrime e corsero verso di lui, e gli fecero domande su ciò che era accaduto e perché avesse quell’aspetto. Ma il principe non rispose a nessuna di esse.

”Dov’è mia moglie?” chiese il principe. Vi fu una pausa di silenzio.

Poi la regina rispose:

“È morta.”

Morta!” ripeté il principe, facendo un passo indietro. “E mio figlio?”

”È morto anche lui.”

Il giovane restò in silenzio. Poi disse: “Mostratemi le loro tombe.”

A queste parole il re, che si sentiva piuttosto a disagio, si fece animo perché non aveva forse allestito due magnifiche tombe da mostrare al figlio, così che non potesse mai indovinare ciò che era stato di sua moglie? In tutti quei mesi il re e la regina si erano detti l’un l’altra quanto fossero stati buoni e compassionevoli nel non seguire il suggerimento del fratello di mettere a morte la ragazza. Ma ora, ciò non sembrava così sicuro.

Allora il re gli fece strada verso il cortile proprio dietro il palazzo e, attraverso il cancello, in un meraviglioso giardino in cui sorgevano due splendide tombe in uno spazio verde tra gli alberi. Il principe avanzò da solo e, posando la testa sulla pietra, scoppiò in lacrime. Il padre e la madre rimasero dietro in silenzio, con una strana fitta nel cuore che non riuscivano a comprendere del tutto. Poteva essere che si vergognassero di loro stessi?

Dopo un po’ il principe si girò e, camminando avanti a loro dentro il palazzo, ordinò che gli schiavi gli portassero gli abiti da lutto. Per sette giorni nessuno lo vide, ma al termine di essi andò a caccia e aiutò il padre come prima a governare il popolo. Solo che nessuno osava parargli della moglie e del figlio.

Infine un mattino, dopo che la ragazza era rimasta sveglia tutta la notte pensando al marito, disse all’amico serpente:

”Mi hai usato tante cortesie, ma ora io sto di nuovo bene e voglio andare a casa a sentire notizie di mio marito, e se mi piange ancora!” A queste parole il cuore del serpente si rattristò, ma disse solo:

”Sì, così deve essere, vai a dire addio a mio padre e amia madre, ma se ti offrono un dono, bada di non accettare altro che l’anello di mio padre e lo scrigno di mia madre.”

Così la ragazza andò dai genitori serpenti, i quali piansero amaramente al pensiero di perderla, e le offrirono oro e gioielli quanti ne avrebbe potuti portare, in loro ricordo. Ma la ragazza scosse la testa e allontanò da sé quel muccio scintillante.

”Non vi dimenticherò mai, mai,” disse con voce rotta, “ma gli unici pegni che accetterò da voi sono questo anellino e questo vecchio scrigno.”

I due serpenti si guardarono l’un l’altra costernati. L’anello e lo scrigno erano le sole due cose che non volevano lei avesse. Poi, dopo una breve pausa, parlarono:

”Perché vuoi tanto l’anello e lo scrigno? Chi te ne ha parlato”

”Oh, nessuno, è solo un mio capriccio.” rispose la ragazza. Ma i vecchi serpenti scossero le teste e risposero:

”Non è così; è stato nostro figlio a parlartene e, se lo ha fatto, così deve essere. Se avrai bisogno di cibo o di vestiti, dillo all’anello e li troverà per te. E se sei infelice o in pericolo, dillo allo scrigno e sistemerà le cose.” Poi la benedissero entrambi e lei prese il bambino e se ne andò.

Camminò per molto tempo finché alla fine giunse vicino alla città in cui vivevano il marito e suo padre. Si fermò sotto un gruppo di palme e disse all’anello che voleva una casa.

”Fatto, padrona.” sussurrò una strana vocina che la fece sobbalzare e, guardandosi attorno, vide un bel palazzo costruito con il legno più pregiato e una fila di schiavi con alti ventagli, che si inchinavano davanti alla porta. Fu molto contenta di entrare perché era assai stanca e, dopo aver mangiato un’ottima cena a base di frutta e di latte che aveva trovato in una delle stanze, si sdraiò su una pila di cuscini e si addormentò con il bambino accanto.

Se ne stette lì tranquilla e ogni giorno il bambino diventava più alto e più robusto, e ben presto poté correre e persino parlare. Naturalmente i vicini avevano un bel po’ da dire su quella casa che era stata costruita così rapidamente, molto rapidamente, alla periferia della città e inventavano ogni genere di storie sulla ricca dama che ci viveva. Di lì a poco, il re tornò dalla guerra con il figlio e alcune di queste chiacchiere giunsero al suo orecchio.

”È davvero strana quella casa tra le palme,” disse alla regina, “devo scoprire qualcosa sulla dama che nessuno ha mai visto. Suppongo che dopotutto non sia una dama, ma piuttosto una banda di cospiratori che vogliono impossessarsi del trono. Domani prenderò mio figlio e il primo ministro e insisteremo per entrare.”

Il giorno dopo all’alba la moglie del principe si trovava su una collinetta dietro la casa quando vide una nuvola di polvere che proveniva dalla città. Un attimo dopo sentì vagamento il rullio dei tamburi che annunciavano la presenza del re e vide una folla di persone che si avvicinava al gruppo di palme. Il suo cuore batté più in fretta. Ci sarebbe stato suo marito tra di loro? In ogni caso non dovevano sorprenderla lì; così, ordinando all’anello di procurare loro del cibo, corse dentro e si avvolse la testa e il volto con un velo di garza d’oro. Poi, prendendo per mano il bambino, andò alla porta e attese.

In pochi minuti arrivò tutta la processione e lei avanzò e li pregò di entrare a riposare.

”Volentieri,” rispose il re; “andate avanti per prima e noi vi seguiremo.”

La seguirono in una vasta sala buia nella quale c’era un tavolo coperto di coppe d’oro e di cestini pieni di datteri, di noci di cocco e di ogni genere di frutti gialli e maturi; il re e suo figlio sedettero sui cuscini e furono serviti dagli schiavi, mentre il primo ministro, in cui riconobbe il fratello, restò dietro di loro.

’Ah, devo a lui tutte le mie sventure,’ si disse. ?mi ha odiata sin dall’inizio.” Ma esteriormente non mostrò nulla. quando il re le chiese che novità vi fossero in città, rispose solo:

”Siete giunti cavalcando da lontano; prima mangiate e bevete perché siete affamati e assetati, poi vi racconterò le mie novità.”

”Parlate con assennatezza.” rispose il re, e il silenziò regnò per parecchio tempo. Poi disse:

”Adesso, mia signora, ho finito, mi sono ristorato, dunque ditemi, vi prego, chi siete e da dove venite? Prima, però, sedetevi.”

La ragazza chino la testa e sedette su un grosso cuscino scarlatto, mettendosi sulle ginocchia il bambino, che dormiva in un angolo, e cominciò a raccontare la storia della propria vita. Mentre il fratello ascoltava, avrebbe voluto lasciare la casa e nascondersi nella foresta, ma era suo compito agitare il ventaglio di piume di pavone sulla testa del re per allontanare le mosche, e sapeva che sarebbe stato catturato dalle guardie reali se avesse tentato di abbandonare il proprio posto. Doveva restare dove si trovava, non c’era scampo per lui, ma per sua fortuna il re era troppo interessato alla storia per notare che il ventaglio aveva smesso di muoversi e che le mosche stava svolazzando in cima ai suoi folti capelli ricciuti.

La storia proseguiva, ma la narratrice non guardò il principe neppure una volta, persino attraverso il velo, sebbene lui al suo fianco non le staccasse gli occhi di dosso.

Quando giunse al punto in cui si era seduta piangendo sull’albero, il figlio del re non seppe trattenersi più a lungo.

”È mia moglie.” gridò, slanciandosi verso il punto in cui lei sedeva con il bambino addormentato in grembo. “Mi hanno mentito, tu non sei affatto morta, e neppure il bambino! Ma che cosa è accaduto? Perché mi hanno mentito? E perché hai lasciato la mia casa in cui eri al sicuro?” e si voltò a guardare il padre con ferocia.

”Prima lasciami finire la mia storia e poi capirai.” Rispose la ragazza, gettando via il velo, e raccontò di come il fratello fosse venuto a palazzo e l’avesse accusata di essere una strega, e di come fosse riuscito a convincere il re a ucciderla “Ma lui non ha voluto farlo,” continuò dolcemente, “e dopotutto, se fossi rimasta nella tua casa, non avrei mai incontrato il serpente, né avrei riavuto indietro la mia mano. Così dimentichiamo tutto e siamo felici ancora una volta perché, vedi? tuo figlio è diventato un proprio un bel ragazzino.”

”Che ne faremo di tuo fratello?” chiese il re, felice di pensare che in quella faccenda qualcuno si fosse comportato peggio di lui.

”Che sia esiliato dalla città.” rispose la ragazza.

Dalle storie swahili raccolte da E. Steere

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)