The Bones of Djulung

(MP3-9'51'')

IN a beautiful island that lies in the southern seas, where chains of gay orchids bind the trees together, and the days and nights are equally long and nearly equally hot, there once lived a family of seven sisters. Their father and mother were dead, and they had no brothers, so the eldest girl ruled over the rest, and they all did as she bade them. One sister had to clean the house, a second carried water from the spring in the forest, a third cooked their food, while to the youngest fell the hardest task of all, for she had to cut and bring home the wood which was to keep the fire continually burning. This was very hot and tiring work, and when she had fed the fire and heaped up in a corner the sticks that were to supply it till the next day, she often threw herself down under a tree, and went sound asleep.

One morning, however, as she was staggering along with her bundle on her back, she thought that the river which flowed past their hut looked so cool and inviting that she determined to bathe in it, instead of taking her usual nap. Hastily piling up her load by the fire, and thrusting some sticks into the flame, she ran down to the river and jumped in. How delicious it was diving and swimming and floating in the dark forest, where the trees were so thick that you could hardly see the sun! But after a while she began to look about her, and her eyes fell on a little fish that seemed made out of a rainbow, so brilliant were the colours he flashed out.

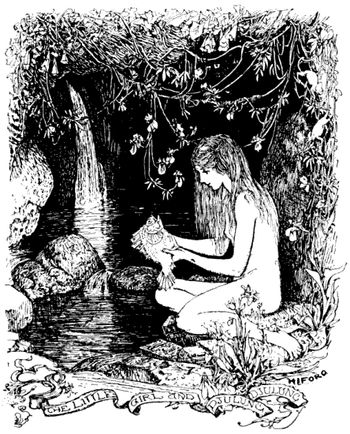

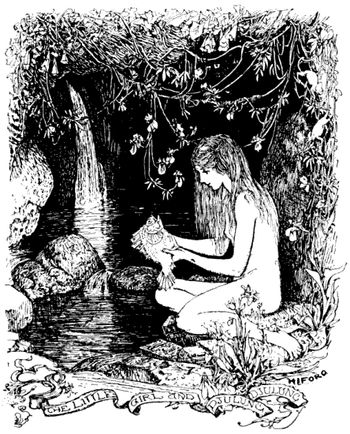

'I should like him for a pet,' thought the girl, and the next time the fish swam by, she put out her hand and caught him. Then she ran along the grassy path till she came to a cave in front of which a stream fell over some rocks into a basin. Here she put her little fish, whose name was Djulung-djulung, and promising to return soon and bring him some dinner, she went away.

By the time she got home, the rice for their dinner was ready cooked, and the eldest sister gave the other six their portions in wooden bowls. But the youngest did not finish hers, and when no one was looking, stole off to the fountain in the forest where the little fish was swimming about.

'See! I have not forgotten you,' she cried, and one by one she let the grains of rice fall into the water, where the fish gobbled them up greedily, for he had never tasted anything so nice.

'That is all for to-day,' she said at last, 'but I will come again to-morrow,' and bidding him good-bye she went down the path.

Now the girl did not tell her sisters about the fish, but every day she saved half of her rice to give him, and called him softly in a little song she had made for herself. If she sometimes felt hungry, no one knew of it, and, indeed, she did not mind that much, when she saw how the fish enjoyed it. And the fish grew fat and big, but the girl grew thin and weak, and the loads of wood felt heavier every day, and at last her sisters noticed it.

Then they took counsel together, and watched her to see what she did, and one of them followed her to the fountain where Djulung lived, and saw her give him all the rice she had saved from her breakfast. Hastening home the sister told the others what she had witnessed, and that a lovely fat fish might be had for the catching. So the eldest sister went and caught him, and he was boiled for supper, but the youngest sister was away in the woods, and did not know anything about it.

Next morning she went as usual to the cave, and sang her little song, but no Djulung came to answer it; twice and thrice she sang, then threw herself on her knees by the edge, and peered into the dark water, but the trees cast such a deep shadow that her eyes could not pierce it.

'Djulung cannot be dead, or his body would be floating on the surface,' she said to herself, and rising to[Pg 212] her feet she set out homewards, feeling all of a sudden strangely tired.

'What is the matter with me?' she thought, but somehow or other she managed to reach the hut, and threw herself down in a corner, where she slept so soundly that for days no one was able to wake her.

At length, one morning early, a cock began to crow so loud that she could sleep no longer; and as he continued to crow she seemed to understand what he was saying, and that he was telling her that Djulung was dead, killed and eaten by her sisters, and that his bones lay buried under the kitchen fire. Very softly she got up, and took up the large stone under the fire, and creeping out carried the bones to the cave by the fountain, where she dug a hole and buried them anew. And as she scooped out the hole with a stick she sang a song, bidding the bones grow till they became a tree—a tree that reached up so high into the heavens that its leaves would fall across the sea into another island, whose king would pick them up.

As there was no Djulung to give her rice to, the girl soon became fat again, and as she was able to do her work as of old, her sisters did not trouble about her. They never guessed that when she went into the forest to gather her sticks, she never failed to pay a visit to the tree, which grew taller and more wonderful day by day. Never was such a tree seen before. Its trunk was of iron, its leaves were of silk, its flowers of gold, and its fruit of diamonds, and one evening, though the girl did not know it, a soft breeze took one of the leaves, and blew it across the sea to the feet of one of the king's attendants.

'What a curious leaf! I have never beheld one like it before. I must show it to the king,' he said, and when the king saw it he declared he would never rest until he had found the tree which bore it, even if he had to spend the rest of his life in visiting the islands that lay all round. Happily for him, he began with the island that was nearest, and here in the forest he suddenly saw standing before him the iron tree, its boughs covered with shining leaves like the one he carried about him.

'But what sort of a tree is it, and how did it get here?' he asked of the attendants he had with him. No one could answer him, but as they were about to pass out of the forest a little boy went by, and the king stopped and inquired if there was anyone living in the neighbourhood whom he might question.

'Seven girls live in a hut down there,' replied the boy, pointing with his finger to where the sun was setting.

'Then go and bring them here, and I will wait,' said the king, and the boy ran off and told the sisters that a great chief, with strings of jewels round his neck, had sent for them.

Pleased and excited the six elder sisters at once followed the boy, but the youngest, who was busy, and who did not care about strangers, stayed behind, to finish the work she was doing. The king welcomed the girls eagerly, and asked them all manner of questions about the tree, but as they had never even heard of its existence, they could tell him nothing. 'And if we, who live close by the forest, do not know, you may be sure no one does,' added the eldest, who was rather cross at finding this was all that the king wanted of them.

'But the boy told me there were seven of you, and there are only six here,' said the king.

'Oh, the youngest is at home, but she is always half asleep, and is of no use except to cut wood for the fire,' replied they in a breath.

'That may be, but perhaps she dreams,' answered the king. 'Anyway, I will speak to her also.' Then he signed to one of his attendants, who followed the path that the boy had taken to the hut.

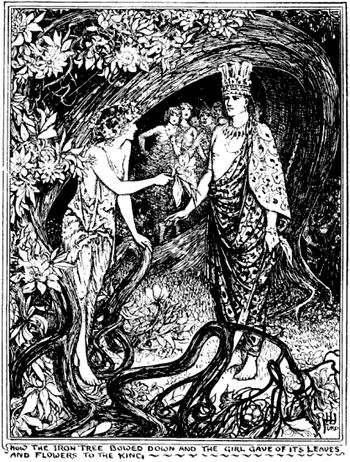

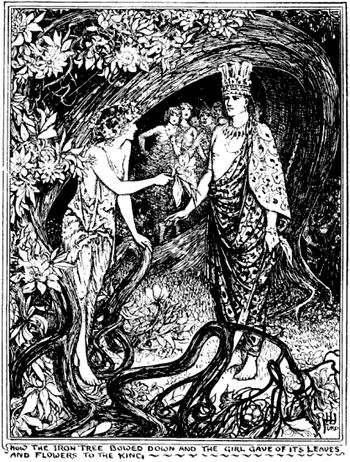

Soon the man returned, with the girl walking behind him. And as soon as she reached the tree, it bowed itself to the earth before her, and she stretched out her hand and picked some of its leaves and flowers and gave them to the king.

'The maiden who can work such wonders is fitted to be the wife of the greatest chief,' he said, and so he married her, and took her with him across the sea to his own home, where they lived happy for ever after.

From Folk Lore,' by A. F. Mackenzie.

Le ossa di Djulung

In una splendida isola dei mari del sud, nella quale catene di vivaci orchidee congiungono tra di loro gli alberi, e il giorno e la notte sono della medesima lunghezza e quasi del medesimo calore, viveva una famiglia di sette sorelle. Il padre e la madre erano morti e non avevano fratelli, così la maggiore governava le altre, che facevano tutto ciò che diceva. Una sorella doveva tenere pulita la casa, una seconda portava l’acqua dalla sorgente nella foresta, una terza cucinava il cibo, mentre la più giovane aveva il compito più gravoso di tutti perché doveva tagliare e portare a casa la legna con cui doveva mantenere il fuoco costantemente acceso. Era un lavoro che accaldava e stancava e, quando aveva alimentato il fuoco e ammucchiato in un angolo i rami che dovevano bastare fino al giorno successivo, spesso si sdraiava sotto un albero e si addormentava profondamente.

In ogni modo una mattina in cui procedeva vacillando con il fagotto sulle spalle, pensò che il fiume che scorreva vicino alla capanna sembrava così fresco e invitante che decise di farvi un bagno, invece di fare il solito sonnellino. Affrettandosi ad ammucchiare il carico presso il fuoco e gettando alcuni rami tra le fiamme, scese di corsa al fiume e vi balzò dentro. Com’era delizioso tuffarsi e nuotare nella cupa foresta in cui gli alberi erano così fitti che a malapena avreste visto il sole! Dopo un po’ cominciò a guardarsi attorno e lo sguardo le cadde su un pesciolino che sembrava fatto di arcobaleno, tanto erano brillanti i colori che sprigionava.

‘Mi piacerebbe averlo come animale domestico.’ pensò la ragazza e il momento dopo in cui il pesce le nuotò vicino, allungò la mano e lo afferrò. Poi corse lungo il sentiero erboso finché giunse a una grotta davanti alla quale una sorgente cadeva dalle rocce in una pozza. Vi mise il pesciolino, che si chiamava Djulung-djulung, e, promettendo di tornare presto a portargli qualcosa per cena, se ne andò.

Nel tempo che le occorse per tornare a casa, il riso per la cena era quasi cotto e la maggiore delle sorelle diede alle altre sei le loro porzioni nelle ciotole di legno. La più giovane non finì la propria e, quando nessuno la stava guardando, si recò alla pozza nella foresta in cui il pesciolino stava nuotando.

“Guarda! Non mi sono dimenticata di te.” gridò e lasciò cadere a uno a uno i chicchi di riso nell’acqua; il pesce li trangugiò avidamente perché non aveva mai assaggiato nulla di così gustoso.

“Per oggi è tutto,” disse alla fine la ragazza, “ma domani tornerò.” E salutandolo, se ne andò lungo il sentiero.

Dovete sapere che la ragazza non disse del pesce alle sorelle, ma ogni giorno conservava un po’ del proprio riso da dargli e lo chiamava dolcemente con un motivetto che si era inventata. Se qualche volta si sentiva affamata, nessuno lo sapeva, e lei davvero non se ne curava troppo, vedendo quanto il pesce gradisse. E il pesce divenne grasso e grande, ma la ragazza diventava magra e debole e i carichi di legna si facevano ogni giorno più pesanti, tanto che alla fine le sue sorelle se ne accorsero.

Allora si consultarono a vicenda e la osservarono per vedere che cosa facesse; una di loro la seguì alla pozza in cui viveva Djulung e la vide dargli tutto il riso che aveva conservato dalla colazione. Affrettandosi a tornare a casa, la sorella disse alle altre ciò di cui era stata testimone e che si sarebbe potuto catturare un bel pesce grasso, così la maggiore delle sorelle andò, lo prese e fu lessato per cena, ma la sorella più giovane era nei boschi e non ne seppe nulla.

Il mattino seguente andò come il solito alla pozza e cantò la canzoncina, ma da Djulung non giunse alcuna risposta; cantò due, tre volte, poi si gettò in ginocchio sul bordo e guardò nell’acqua scura, ma gli alberi gettavano ombre così profonde che il suo sguardo non potevano trapassarla.

‘Djulung non può essere morto o il suo corpo galleggerebbe in superficie.’ si disse e, sollevandosi, tornò verso casa, sentendosi all’improvviso stranamente stanca.

‘Che cosa mi sta accadendo?’ pensò, ma in un modo o nell’altro riuscì a raggiungere la capanna e a gettarsi in un angolo, dove dormì così profondamente che per giorni nessuno riuscì a svegliarla.

Infine una mattina presto un gallo cominciò a cantare così forte che lei non poté dormire più a lungo; e siccome continuava a cantare, le sembrò di capire che cosa stesse dicendo; le stava raccontando che Djulung era morto, ucciso e mangiato dalle sue sorelle, e che le sue ossa erano sepolte sotto il focolare della cucina. La ragazza sia alzò assai silenziosamente e sollevò la larga pietra sotto il focolare, poi, sgusciando fuori, portò le ossa nella grotta presso la pozza, dove scavò un buco e le seppellì di nuovo. E mentre scavava la buca con un bastoncino, cantava una canzone, ordinando alle ossa di crescere finché diventarono un albero – un albero che diventò così alto nel cielo che le sue foglie caddero oltre il mare su un’altra isola in cui il re le raccolse.

Siccome non c’era più Djulung al quale dare il riso, la ragazza ben presto ritornò in carne e siccome era in grado di svolgere il proprio lavoro come in precedenza, le sue sorelle non si preoccuparono di lei. Non avrebbero mai potuto immaginare che, quando andava nella foresta a raccogliere i ramoscelli, non mancava mai di far visita all’albero, che di giorno in giorno diventava sempre più alto e più bello. Né si era mai visto prima un albero simile. Il tronco era d’acciaio, le foglie di seta, i fiori d’oro e i frutti di diamanti; ogni sera, sebbene la ragazza non lo sapesse, una brezza leggera staccava una foglia e la soffiava di là dal mare ai piedi di uno degli attendenti del re.

“Che foglia particolare! Ne non avevo mai vista prima una così. Devo mostrarla al re.” disse, e quando il re la vide, affermò che non avrebbe avuto pace finché non avesse trovato l’albero che la produceva, pur se avesse dovuto impiegare tutto il resto della vita visitando le isole dei dintorni. Fortunatamente per lui, cominciò con l’isola più vicina e lì nella foresta vide improvvisamente davanti a sé l’albero d’acciaio, i cui rami erano coperti di foglie scintillanti come quella che aveva portato con sé.

“Che razza di albero è, e come si trova qui?” chiese agli attendenti che erano con lui. Nessuno poté rispondergli, ma mentre stavano per lasciare la foresta, giunse un bambino e il re lo fermò e gli chiese se nelle vicinanze vivesse qualcuno al quale potesse chiedere.

“Laggiù in una capanna vivono sette ragazze.” rispose il bambino, puntando il dito verso il sole che stava calando.

“Allora vai e conducile qui, io aspetterò.” disse il re, e il bambino corse e disse alle sorelle che le stava aspettando un grande capo con collane di gioielli intorno al collo.

Compiaciute ed eccitate le sei sorelle più grandi seguirono subito il bambino, ma la più giovane, che era affaccendata e non si interessava agli stranieri, rimase indietro a terminare il lavoro che stava svolgendo. Il re accolse le ragazze con ansia e rivolse loro ogni genere di domande sull’albero, ma siccome loro non avevano mai sentito parlare della sua esistenza, non gli poterono dire nulla. “E se non lo sappiamo noi, che viviamo vicino alla foresta, potete star certo che nessuno lo sappia.” aggiunse la maggiore, che era piuttosto arrabbiata alla scoperta che ciò era tutto quello che il re voleva da loro.

“Il bambino mi ha detto che eravate sette, ma qui siete solo in sei.” disse il re.

“La più giovane è a casa, ma è sempre mezzo addormentata e non serve ad altro che a tagliare la legna per il fuoco.” risposero sottovoce.

“È possibile, ma forse sogna,” rispose il re. “In ogni modo parlerò anche con lei.” Allora fece cenno a uno degli attendenti, il quale seguì il sentiero percorso dal bambino verso la capanna.

Ben presto l’uomo tornò con la ragazza dietro di sé. Appena ebbe raggiunto l’albero, esso s’inchinò fino a terra di fronte a lei e la ragazza allungò le mani e colse un po’ di foglie e di fiori e li diede al re.

“La fanciulla che può svolgere un lavoro così meraviglioso è degna di diventare la moglie del più grande capo.” disse il re e così la sposò, la portò con sé oltre il mare fino a casa propria, dove vissero felici e contenti per sempre.

Origine sconosciuta, tratta da Folclore di A.F. Mackenzie.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)