The Castle of Kerglas

(MP3-28'57'')

PERONNIK was a poor idiot who belonged to nobody, and he would have died of starvation if it had not baking a hole in it, crept in, like a lizard. Idiot though he was, he was never unhappy, but always thanked gratefully those who fed him, and sometimes would stop foeen for the kindness of the village people, who gave him food whenever he chose to ask for it. And as for a bed, when night came, and he grew sleepy, he looked about for a heap of straw, and mr a little and sing to them. For he could imitate a lark so well, that no one knew which was Peronnik and which was the bird.

He had been wandering in a forest one day for several hours, and when evening approached, he suddenly felt very hungry. Luckily, just at that place the trees grew thinner, and he could see a small farmhouse a little way off. Peronnik went straight towards it, and found the farmer's wife standing at the door holding in her hands the large bowl out of which her children had eaten their supper.

'I am hungry, will you give me something to eat?' asked the boy.

'If you can find anything here, you are welcome to it,' answered she, and, indeed, there was not much left, as everybody's spoon had dipped in. But Peronnik ate what was there with a hearty appetite, and thought that he had never tasted better food.

'It is made of the finest flour and mixed with the richest milk and stirred by the best cook in all the countryside,' and though he said it to himself, the woman heard him.

'Poor innocent,' she murmured, 'he does not know what he is saying, but I will cut him a slice of that new wheaten loaf,' and so she did, and Peronnik ate up every crumb, and declared that nobody less than the bishop's baker could have baked it. This flattered the farmer's wife so much that she gave him some butter to spread on it, and Peronnik was still eating it on the doorstep when an armed knight rode up.

'Can you tell me the way to the castle of Kerglas?' asked he.

'To Kerglas? are you really going to Kerglas?' cried the woman, turning pale.

'Yes; and in order to get there I have come from a country so far off that it has taken me three months' hard riding to travel as far as this.'

'And why do you want to go to Kerglas?' said she.

'I am seeking the basin of gold and the lance of diamonds which are in the castle,' he answered. Then Peronnik looked up.

'The basin and the lance are very costly things,' he said suddenly.

'More costly and precious than all the crowns in the world,' replied the stranger, 'for not only will the basin furnish you with the best food that you can dream of, but if you drink of it, it will cure you of any illness however dangerous, and will even bring the dead back to life, if it touches their mouths. As to the diamond lance, that will cut through any stone or metal.'

'And to whom do these wonders belong?' asked Peronnik in amazement.

'To a magician named Rogéar who lives in the castle,' answered the woman. 'Every day he passes along[ he

re, mounted on a black mare, with a colt thirteen months old trotting behind. But no one dares to attack him, as he always carries his lance.'

'That is true,' said the knight, 'but there is a spell laid upon him which forbids his using it within the castle of Kerglas. The moment he enters, the basin and lance are put away in a dark cellar which no key but one can open. And that is the place where I wish to fight the magician.'

'You will never overcome him, Sir Knight,' replied the woman, shaking her head. 'More than a hundred gentlemen have ridden past this house bent on the same errand, and not one has ever come back.'

'I know that, good woman,' returned the knight, 'but then they did not have, like me, instructions from the hermit of Blavet.'

'And what did the hermit tell you?' asked Peronnik.

'He told me that I should have to pass through a wood full of all sorts of enchantments and voices, which would try to frighten me and make me lose my way. Most of those who have gone before me have wandered they know not where, and perished from cold, hunger, or fatigue.'

'Well, suppose you get through safely?' said the idiot.

'If I do,' continued the knight, 'I shall then meet a sort of fairy armed with a needle of fire which burns to ashes all it touches. This dwarf stands guarding an apple-tree, from which I am bound to pluck an apple.'

'And next?' inquired Peronnik.

'Next I shall find the flower that laughs, protected by a lion whose mane is formed of vipers. I must pluck that flower, and go on to the lake of the dragons and fight the black man who holds in his hand the iron ball which never misses its mark and returns of its own accord to its master. After that, I enter the valley of pleasure, where some who conquered all the other obstacles have left their bones. If I can win through this, I shall reach a river with only one ford, where a lady in black will be seated. She will mount my horse behind me, and tell me what I am to do next.'

He paused, and the woman shook her head.

'You will never be able to do all that,' said she, but he bade her remember that these were only matters for men, and galloped away down the path she pointed out.

The farmer's wife sighed and, giving Peronnik some more food, bade him good-night. The idiot rose and was opening the gate which led into the forest when the farmer himself came up.

'I want a boy to tend my cattle,' he said abruptly, 'as the one I had has run away. Will you stay and do it?' and Peronnik, though he loved his liberty and hated work, recollected the good food he had eaten, and agreed to stop.

At sunrise he collected his herd carefully and led them to the rich pasture which lay along the borders of the forest, cutting himself a hazel wand with which to keep them in order.

His task was not quite so easy as it looked, for the cows had a way of straying into the wood, and by the time he had brought one back another was off. He had gone some distance into the trees, after a naughty black cow which gave him more trouble than all the rest, when he heard the noise of horse's feet, and peeping through the leaves he beheld the giant Rogéar seated on his mare, with the colt trotting behind. Round the giant's neck hung the golden bowl suspended from a chain, and in his hand he grasped the diamond lance, which gleamed like fire. But as soon as he was out of sight the idiot sought in vain for traces of the path he had taken.

This happened not only once but many times, till Peronnik grew so used to him that he never troubled to hide. But on each occasion he saw him the desire to possess the bowl and the lance became stronger.

One evening the boy was sitting alone on the edge of the forest, when a man with a white beard stopped beside him. 'Do you want to know the way to Kerglas?' asked the idiot, and the man answered 'I know it well.'

'You have been there without being killed by the magician?' cried Peronnik.

'Oh! he had nothing to fear from me,' replied the white-bearded man, 'I am Rogéar's elder brother, the wizard Bryak. When I wish to visit him I always pass this way, and as even I cannot go through the enchanted wood without losing myself, I call the colt to guide me.' Stooping down as he spoke he traced three circles on the ground and murmured some words very low, which Peronnik could not hear. Then he added aloud:

Colt, free to run and free to eat,

Colt, gallop fast until we meet.

and instantly the colt appeared, frisking and jumping to the wizard, who threw a halter over his neck and leapt on his back.

Peronnik kept silence at the farm about this adventure, but he understood very well that if he was ever to get to Kerglas he must first catch the colt which knew the way. Unhappily he had not heard the magic words uttered by the wizard, and he could not manage to draw the three circles, so if he was to summon the colt at all he must invent some other means of doing it.

All day long, while he was herding the cows, he thought and thought how he was to call the colt, for he felt sure that once on its back he could overcome the other dangers. Meantime he must be ready in case a chance should come, and he made his preparations at night, when every one was asleep. Remembering what he had seen the wizard do, he patched up an old halter that was hanging in a corner of the stable, twisted a rope of hemp to catch the colt's feet, and a net such as is used for snaring birds. Next he sewed roughly together some bits of cloth to serve as a pocket, and this he filled with glue and larks' feathers, a string of beads, a whistle of elder wood, and a slice of bread rubbed over with bacon fat. Then he went out to the path down which Rogéar, his mare, and the colt always rode, and crumbled the bread on one side of it.

Punctual to their hour all three appeared, eagerly watched by Peronnik, who lay hid in the bushes close by. Suppose it was useless; suppose the mare, and not the colt, ate the crumbs? Suppose—but no! the mare and her rider went safely by, vanishing round a corner, while the colt, trotting along with its head on the ground, smelt the bread, and began greedily to lick up the pieces. Oh, how good it was! Why had no one ever given it that before, and so absorbed was the little beast, sniffing about after a few more crumbs, that it never heard Peronnik creep up till it felt the halter on its neck and the rope round its feet, and—in another moment—some one on its back.

Going as fast as the hobbles would allow, the colt turned into one of the wildest parts of the forest, while its rider sat trembling at the strange sights he saw. Sometimes the earth seemed to open in front of them and he was looking into a bottomless pit; sometimes the trees burst into flames and he found himself in the midst of a fire; often in the act of crossing a stream the water rose and threatened to sweep him away; and again, at the foot of a mountain, great rocks would roll towards him, as if they would crush him and his colt beneath their weight. To his dying day Peronnik never knew whether these things were real or if he only imagined them, but he pulled down his knitted cap so as to cover his eyes, and trusted the colt to carry him down the right road.

At last the forest was left behind, and they came out on a wide plain where the air blew fresh and strong. The idiot ventured to peep out, and found to his relief that the enchantments seemed to have ended, though a thrill of horror shot through him as he noticed the skeletons of men scattered over the plain, beside the skeletons of their horses. And what were those grey forms trotting away in the distance? Were they—could they be—wolves?

But vast though the plain seemed, it did not take long to cross, and very soon the colt entered a sort of shady park in which was standing a single apple-tree, its branches bowed down to the ground with the weight of its fruit. In front was the korigan—the little fairy man—holding in his hand the fiery sword, which reduced to ashes everything it touched. At the sight of Peronnik he uttered a piercing scream, and raised his sword, but without appearing surprised the youth only lifted his cap, though he took care to remain at a little distance.

'Do not be alarmed, my prince,' said Peronnik, 'I am just on my way to Kerglas, as the noble Rogéar has begged me to come to him on business.'

'Begged you to come!' repeated the dwarf, 'and who, then, are you?'

'I am the new servant he has engaged, as you know very well,' answered Peronnik.

'I do not know at all,' rejoined the korigan sulkily, 'and you may be a robber for all I can tell.'

'I am so sorry,' replied Peronnik, 'but I may be wrong in calling myself a servant, for I am only a bird-catcher. But do not delay me, I pray, for his highness the magician expects me, and, as you see, has lent me his colt so that I may reach the castle all the quicker.'

At these words the korigan cast his eyes for the first time on the colt, which he knew to be the one belonging to the magician, and began to think that the young man was speaking the truth. After examining the horse, he studied the rider, who had such an innocent, and indeed vacant, air that he appeared incapable of inventing a story. Still, the dwarf did not feel quite sure that all was right, and asked what the magician wanted with a bird-catcher.

'From what he says, he wants one very badly,' replied Peronnik, 'as he declares that all his grain and all the fruit in his garden at Kerglas are eaten up by the birds.'

'And how are you going to stop that, my fine fellow?' inquired the korigan; and Peronnik showed him the snare he had prepared, and remarked that no bird could possibly escape from it.

'That is just what I should like to be sure of,' answered the korigan. 'My apples are completely eaten up by blackbirds and thrushes. Lay your snare, and if you can manage to catch them, I will let you pass.'

'That is a fair bargain,' and as he spoke Peronnik jumped down and fastened his colt to a tree; then, stooping, he fixed one end of the net to the trunk of the apple-tree, and called to the korigan to hold the other while he took out the pegs. The dwarf did as he was bid, when suddenly Peronnik threw the noose over his neck and drew it close, and the korigan was held as fast as any of the birds he wished to snare.

Shrieking with rage, he tried to undo the cord, but he only pulled the knot tighter. He had put down the sword on the grass, and Peronnik had been careful to fix the net on the other side of the tree, so that it was now easy for him to pluck an apple and to mount his horse, without being hindered by the dwarf, whom he left to his fate.

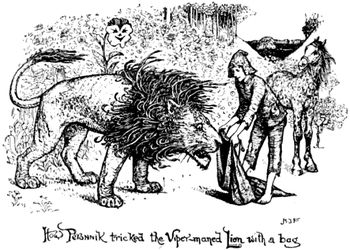

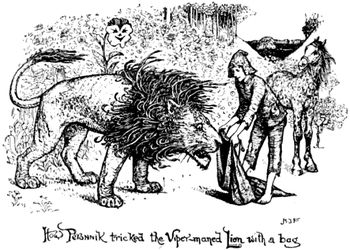

When they had left the plain behind them, Peronnik and his steed found themselves in a narrow valley in which was a grove of trees, full of all sorts of sweet-smelling things—roses of every colour, yellow broom, pink honeysuckle—while above them all towered a wonderful scarlet pansy whose face bore a strange expression. This was the flower that laughs, and no one who looked at it could help laughing too. Peronnik's heart beat high at the thought that he had reached safely the second trial, and he gazed quite calmly at the lion with the mane of vipers twisting and twirling, who walked up and down in front of the grove.

The young man pulled up and removed his cap, for, idiot though he was, he knew that when you have to do with people greater than yourself, a cap is more useful in the hand than on the head. Then, after wishing all kinds of good fortune to the lion and his family, he inquired if he was on the right road to Kerglas.

'And what is your business at Kerglas?' asked the lion with a growl, and showing his teeth.

'With all respect,' answered Peronnik, pretending to be very frightened, 'I am the servant of a lady who is a friend of the noble Rogéar and sends him some larks for a pasty.'

'Larks?' cried the lion, licking his long whiskers. 'Why, it must be a century since I have had any! Have you a large quantity with you?'

'As many as this bag will hold,' replied Peronnik, opening, as he spoke, the bag which he had filled with feathers and glue; and to prove what he said, he turned his back on the lion and began to imitate the song of a lark.

'Come,' exclaimed the lion, whose mouth watered, 'show me the birds! I should like to see if they are fat enough for my master.'

'I would do it with pleasure,' answered the idiot, 'but if I once open the bag they will all fly away.'

'Well, open it wide enough for me to look in,' said the lion, drawing a little nearer.

Now this was just what Peronnik had been hoping for, so he held the bag while the lion opened it carefully and put his head right inside, so that he might get a good mouthful of larks. But the mass of feathers and glue stuck to him, and before he could pull his head out again Peronnik had drawn tight the cord, and tied it in a knot that no man could untie. Then, quickly gathering the flower that laughs, he rode off as fast as the colt could take him.

The path soon led to the lake of the dragons, which had to swim across. The colt, who was accustomed to it, plunged into the water without hesitation; but as soon as the dragons caught sight of Peronnik they approached from all parts of the lake in order to devour him.

This time Peronnik did not trouble to take off his cap, but he threw the beads he carried with him into the water, as you throw black corn to a duck, and with each bead that he swallowed a dragon turned on his back and died, so that the idiot reached the other side without further trouble.

The valley guarded by the black man now lay before him, and from afar Peronnik beheld him, chained by one foot to a rock at the entrance, and holding the iron ball which never missed its mark and always returned to its master's hand. In his head the black man had six eyes that were never all shut at once, but kept watch one after the other. At this moment they were all open, and Peronnik knew well that if the black man caught a glimpse of him he would cast his ball. So, hiding the colt behind a thicket of bushes, he crawled along a ditch and crouched close to the very rock to which the black man was chained.

The day was hot, and after a while the man began to grow sleepy. Two of his eyes closed, and Peronnik sang gently. In a moment a third eye shut, and Peronnik sang on. The lid of a fourth eye dropped heavily, and then those of the fifth and the sixth. The black man was asleep altogether.

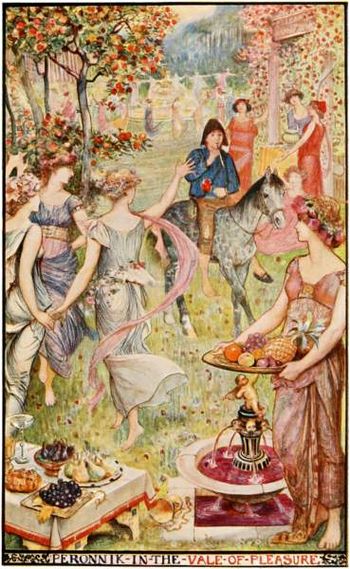

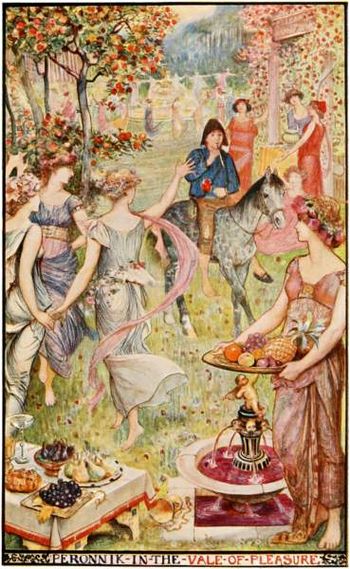

Then, on tiptoe, the idiot crept back to the colt, which he led over soft moss past the black man into the vale of pleasure, a delicious garden full of fruits that dangled before your mouth, fountains running with wine, and flowers chanting in soft little voices. Further on, tables were spread with food, and girls dancing on the grass called to him to join them.

Peronnik heard, and, scarcely knowing what he did, drew the colt into a slower pace. He sniffed greedily the smell of the dishes, and raised his head the better to see the dancers. Another instant and he would have stopped altogether and been lost, like others before him, when suddenly there came to him like a vision the golden bowl and the diamond lance. Drawing his whistle from his pocket, he blew it loudly, so as to drown the sweet sounds about him, and ate what was left of his bread and bacon to still the craving of the magic fruits. His eyes he fixed steadily on the ears of the colt, that he might not see the dancers.

In this way he was able to reach the end of the garden, and at length perceived the castle of Kerglas, with the river between them which had only one ford. Would the lady be there, as the old man had told him? Yes, surely that was she, sitting on a rock, in a black satin dress, and her face the colour of a Moorish woman's. The idiot rode up, and took off his cap more politely than ever, and asked if she did not wish to cross the river.

'I was waiting for you to help me do so,' answered she. 'Come near, that I may get up behind you.'

Peronnik did as she bade him, and by the help of his arm she jumped nimbly on to the back of the colt.

'Do you know how to kill the magician?' asked the lady, as they were crossing the ford.

'I thought that, being a magician, he was immortal, and that no one could kill him,' replied Peronnik.

'Persuade him to taste that apple, and he will die, and if that is not enough I will touch him with my finger, for I am the plague,' answered she.

'But if I kill him, how am I to get the golden bowl and the diamond lance that are hidden in the cellar without a key?' rejoined Peronnik.

'The flower that laughs opens all doors and lightens all darkness,' said the lady; and as she spoke, they reached the further bank, and advanced towards the castle.

In front of the entrance was a sort of tent supported on poles, and under it the giant was sitting, basking in the sun. As soon as he noticed the colt bearing Peronnik and the lady, he lifted his head, and cried in a voice of thunder:

'Why, it is surely the idiot, riding my colt thirteen months old!'

'Greatest of magicians, you are right,' answered Peronnik.

'And how did you manage to catch him?' asked the giant.

'By repeating what I learnt from your brother Bryak on the edge of the forest,' replied the idiot. 'I just said—

Colt, free to run and free to eat,

Colt, gallop fast until we meet.

and it came directly.'

'You know my brother, then?' inquired the giant. 'Tell me why he sent you here.'

'To bring you two gifts which he has just received from the country of the Moors,' answered Peronnik: 'the apple of delight and the woman of submission. If you eat the apple you will not desire anything else, and if you take the woman as your servant you will never wish for another.'

'Well, give me the apple, and bid the woman get down,' answered Rogéar.

The idiot obeyed, but at the first taste of the apple the giant staggered, and as the long yellow finger of the woman touched him he fell dead.

Leaving the magician where he lay, Peronnik entered the palace, bearing with him the flower that laughs. Fifty doors flew open before him, and at length he reached a long flight of steps which seemed to lead into the bowels of the earth. Down these he went till he came to a silver door without a bar or key. Then he held up high the flower that laughs, and the door slowly swung back, displaying a deep cavern, which was as bright as day from the shining of the golden bowl and the diamond lance. The idiot hastily ran forward and hung the bowl round his neck from the chain which was attached to it, and took the lance in his hand. As he did so, the ground shook beneath him, and with an awful rumbling the palace disappeared, and Peronnik found himself standing close to the forest where he led the cattle to graze.

Though darkness was coming on, Peronnik never thought of entering the farm, but followed the road which led to the court of the duke of Brittany. As he passed through the town of Vannes he stopped at a tailor's shop, and bought a beautiful costume of brown velvet and a white horse, which he paid for with a handful of gold that he had picked up in the corridor of the castle of Kerglas. Thus he made his way to the city of Nantes, which at that moment was besieged by the French.

A little way off, Peronnik stopped and looked about him. For miles round the country was bare, for the enemy had cut down every tree and burnt every blade of corn; and, idiot though he might be, Peronnik was able to grasp that inside the gates men were dying of famine. He was still gazing with horror, when a trumpeter appeared on the walls, and, after blowing a loud blast, announced that the duke would adopt as his heir the man who could drive the French out of the country.

On the four sides of the city the trumpeter blew his blast, and the last time Peronnik, who had ridden up as close as he might, answered him.

'You need blow no more,' said he, 'for I myself will free the town from her enemies.' And turning to a soldier who came running up, waving his sword, he touched him with the magic lance, and he fell dead on the spot. The men who were following stood still, amazed. Their comrade's armour had not been pierced, of that they were sure, yet he was dead, as if he had been struck to the heart. But before they had time to recover from their astonishment, Peronnik cried out:

'You see how my foes will fare; now behold what I can do for my friends,' and, stooping down, he laid the golden bowl against the mouth of the soldier, who sat up as well as ever. Then, jumping his horse across the trench, he entered the gate of the city, which had opened wide enough to receive him.

The news of these marvels quickly spread through the town, and put fresh spirit into the garrison, so that they declared themselves able to fight under the command of the young stranger. And as the bowl restored all the dead Bretons to life, Peronnik soon had an army large enough to drive away the French, and fulfilled his promise of delivering his country.

As to the bowl and the lance, no one knows what became of them, but some say that Bryak the sorcerer managed to steal them again, and that any one who wishes to possess them must seek them as Peronnik did. .

From Le Foyer Breton' par Emile Souvestre.

Il castello di Kerglas

PERONNIK era un povero sciocco senza parenti e sarebbe morto di fame se non fosse stato per la gentilezza degli abitanti del villaggio, che gli davano cibo ogni volta in cui decideva di chiederlo. Quanto al letto, quando calava la notte e gli veniva sonno, cercava un mucchio di paglia e, ricavandovi una nicchia, vi scivolava dentro come una lucertola. Per quanto fosse stupido, non era mai infelice e ringraziava sempre calorosamente color che lo nutriva e a volte si fermava per un po’ e cantava per loro. Perché sapeva imitare così bene l’allodola che nessuno poteva distinguere quando fosse Peronnik e quando fosse l’uccello.

Un giorno aveva gironzolato diverse ore nella foresta e, quando si fece sera, improvvisamente si sentì molto affamato. Per fortuna proprio in quel punto gli alberi erano più radi e poté vedere una piccola fattoria non lontano da lì. Peronnik vi si diresse subito e scoprì che la moglie del fattore stava sulla soglia, tenendo in mano la grande scodella dalla quale i suoi bambini avevano mangiato la cena.

“Sono affamato, mi dareste qualcosa da mangiare?” chiese il ragazzo.

“Se puoi trovare qualcosa qui, prego.” rispose la donna, e in effetti non era rimasto molto siccome tutti i cucchiai vi erano stati immersi. Ma Peronnik mangiò quel che c’era con robusto appetito e pensò di non aver mai assaggiato cibo migliore.

‘È fatto con la farina migliore, amalgamata con il latte più cremoso e mescolata dalla miglio cuoca di tutto il paese.’ e sebbene lo dicesse a se stesso, la donna lo sentì.

“Povero sempliciotto,” mormorò la donna “non sa quello che sta dicendo, ma gli taglierò una fetta di quella pagnotta fresca di frumento.” e così fece. Perronik mangiò fino all’ultima briciola e dichiarò che nessuno all’infuori del fornaio del vescovo doveva averla preparata. Ciò lusingò tanto la moglie del fattore che gli diede un po’ di burro da spalmarvi sopra e Perronik stava soddisfatto sulla soglia a mangiare quando giunse un cavaliere armato.

“Potete indicarmi la strada per il castello di Kerglas?” chiese.

“Per Kerglas? Volete andare davvero a Kerglas?” esclamò la donna, impallidendo.

“Sì, e per questo motivo sono venuto da un paese così lontano che ha richiesto un duro viaggio di tre mesi a cavallo.”

“E perché volete andare a Kerglas?” chiese la donna.

“Sto cercando la coppa d’oro e la lancia di diamanti che si trovano nel castello.” rispose il cavaliere. Allora Peronnik alzò lo sguardo.

“La coppa e la lancia sono oggetti molto costosi.” disse improvvisamente.

“Più costosi e preziosi di tutte le corone del mondo.” rispose lo straniero “perché non solo la coppa ti fornisce il miglior cibo tu possa sognare, ma se bevi da esso, curerai ogni tua malattia persino la più pericolosa e potrai tornare perfino dalla vita alla morte, se ti sfiora le labbra. E così la lancia di diamanti, che può tagliare qualsiasi pietra o metallo.”

“E a chi appartengono queste meraviglie?” chiese sbalordito Peronnik.

“A un mago di nome Rogéar, che vive nel castello.” rispose la donna. “Ogni giorno passa qui davanti, in sella a una giumenta nera, seguito al trotto da un puledro di tredici mesi. Siccome porta sempre con sé la lancia, nessuno osa attaccarlo.”

“È vero,” disse il cavaliere, “ma su di lui c’è un incantesimo che gli impedisce di usarli nel castello di Kerglas. Nel momento in cui vi entra, la coppa e la lancia vengono posti in una cella oscura che nessuna chiave tranne una può aprire. E quello è il luogo in cui voglio combattere il mago.”

“Non lo sconfiggerai mai, cavaliere,” replicò la donna, scuotendo la testa. “Più di cento gentiluomini sono passati da questa casa con il medesimo scopo e nessuno è mai tornato indietro.”

“Lo so, brava donna,” rispose il cavaliere, “ma non avevano ricevuto istruzioni dall’eremita di Blavet, come me.”

“Che cosa ti ha detto l’eremita?” chiese Peronnik.

“Mi ha detto che sarei dovuto passare attraverso un bosco pieno di ogni sorta di incantesimi e di voci che avrebbero tentato di spaventarmi e di farmi smarrire la strada. Molti di quelli che erano venuti prima di me avevano vagato senza sapere dove andassero ed erano morti di freddo, di fame o di fatica.”

“Ebbene, tu ritieni di passarvi in mezzo senza pericolo?” chiese lo sciocco.

“Se lo farò,” proseguì il cavaliere, “allora incontrerò una specie di creatura fatata armata di un ago di fuoco che riduce in cenere tutto ciò che tocca. Questo gnomo sta a guardia di un melo dal quale io sono obbligato a cogliere una mela.”

“E poi?” chiese Peronnik.

“Poi troverò il fiore che ride, protetto da un leone la cui criniera è fatta di vipere. Io devo cogliere quel fiore, andare al lago del drago e combattere con l’uomo nero che regge in mano la palla d’acciaio che non fallisce mai un colpo e ritorna spontaneamente dal suo padrone. Dopo di che entrerò nella valle del piacere in cui molti che hanno superato tutti gli altri ostacoli hanno lasciato le ossa. Se ne uscirò vincitore, raggiungerò un fiume con un solo guado presso il quale è seduta una dama vestita di nero. Lei salirà a cavallo dietro di me e mi dirà che cosa dovrò fare dopo.”

Il cavaliere smise di parlare e la donna scosse la testa.

“Non riuscirai mai a fare tutto ciò.” gli disse, ma lui le disse di rammentare che quelle erano cose solo da uomini e galoppò via lungo il sentiero che lei gli indicò.

La moglie del fattore sospirò e, dando ancora un po’ di cibo a Peronnik, gli augurò la buonanotte. Lo sciocco si alzò e stava aprendo il cancello che conduceva nella foresta quando venne il fattore in persona.

“Mi serve un ragazzo che badi al bestiame” disse bruscamente “perché quello che avevo è scappato. Resterai qui a farlo?” e Peronnik, sebbene amasse la libertà e odiasse lavorare, rammentò il buon cibo che aveva mangiato e acconsentì a fermarsi.

all’alba radunò accuratamente il bestiame e lo condusse nel ricco pascolo che si trovava ai margini della foresta, tagliandosi da sé un bastone di nocciolo con il quale condurlo in ordine.

Il suo compito non era facile come sembrava perché le mucche tendevano ad allontanarsi nel bosco e quando ne riportava indietro una, se ne andava un’altra. Aveva percorso una certa distanza tra gli alberi, dietro una capricciosa mucca nera che lo faceva tribolare più di tutte le altre, quando sentì un rumore di zoccoli di cavallo e, sbirciando tra le foglie, vide il gigantesco Rogéar sulla sua giumenta, con il puledro che gli trotterellava dietro. Al collo del gigante pendeva la coppa d’oro appeso a una catena e in mano teneva la lancia di diamanti, luminosa come il fuoco. Ma appena lo perse di vista, lo sciocco cercò invano le sue tracce sul sentiero che aveva preso.

Ciò accadde non una volta sola ma più volte finché Perronik si fu così abituato a lui che non si curava più di nascondersi. Ma ogni volta in cui lo vedeva, il desiderio di possedere la coppa e la lancia diventava più forte.

Una sera il ragazzo era tutto solo al margine della foresta quando un uomo con la barba bianca gli si fermò accanto. “Vuoi conoscere la strada per Kerglas?” chiese lo sciocco e l’uomo rispose: “La conosco bene.”

“Sei stato là senza essere stato ucciso dal mago?” gridò Peronnik.

“Non ha nulla da temere da me,” rispose l’uomo con la barba bianca “sono il fratello maggiore di Rogéar, il mago Bryak. Quando desidero andare a fargli visita, passo sempre per questa strada e siccome non posso passare per il bosco incantato senza perdermi, chiamo il puledro a guidarmi.” Chinandosi mentre parlava, tracciò tre cerchi sul terreno e mormorò assai piano alcune parole che Peronnik non poté udire. Poi aggiunse a voce alta:

Puledro, libero di correre e di mangiare,

galoppa veloce fino a farci incontrare.

e immediatamente comparve il puledro, sgambettando e saltellando verso il mago, il quale gli gettò al collo le briglie e gli salì sul dorso.

Peronnik alla fattoria tacque sulla sua avventura, ma capiva benissimo che, se mai volesse andare a Kerglas, prima doveva catturare il puledro che conosceva la strada. Sfortunatamente non aveva sentito le parole magiche borbottate dal mago e non sarebbe riuscito a disegnare i tre cerchi, così se doveva convocare il puledro, avrebbe dovuto inventarsi qualche altro modo per farlo.

Per tutto il giorno, mentre faceva pascolare il bestiame, pensò e ripensò al modo in cui chiamare il puledro perché si sentiva sicuro del fatto che, una volta in sella, avrebbe superato gli altri pericoli. Nel frattempo doveva esser pronto, in caso avesse avuto un’opportunità, e fece i preparativi di notte, quando tutti dormivano. Rammentando ciò che aveva visto fare al mago, aggiusto delle vecchie briglie che erano appese in un angolo della stalla, arrotolò una corda di canapa per catturare le zampe del puledro e una rete come quelle che si usavano per intrappolare gli uccelli. Poi cucì grossolanamente alcuni frammenti di abito che gli servissero come sacco e lo riempì di colla e piume di allodola, fili di perline, un fischietto di legno stagionato e una fetta di pane spalmata di grasso di maiale. Poi andò sul sentiero lungo il quale cavalcavano sempre Rogéar, la sua giumenta e il puledro e vi sbriciolò il pane da un lato.

Alla solita ora apparvero tutti e tre, osservati attentamente da Peronnik, il quale stava nascosto nei cespugli vicini. Supponiamo che fosse inutile; supponiamo che la giumenta, e non il puledro, mangiasse le briciole? Supponiamo – ma no! La giumenta e il suo cavaliere proseguirono tranquillamente, svanendo alla svolta, mentre il puledro, che trotterellava con la testa china sul terreno, annusò il pane e cominciò a leccare avidamente le briciole. Andava a meraviglia! Siccome nessuno gliene aveva mai date prima e la bestiola era così assorta ad annusare in cerca di altre briciole, neppure udì Peronnik sgattaiolare finché non sentì le briglie sul collo e la fune intorno alle zampe e, un attimo dopo, un’altra sul dorso.

Andando il più velocemente gli consentisse l’andatura zoppicante, il puledro si si addentrò in una delle parti più selvagge della foresta mentre il suo cavaliere sedeva tremando alle strane cose che vedeva. Talvolta sembrava che la terra si aprisse davanti a loro e lui stesse guardando in una cavità senza fondo; talvolta gli alberi prendevano fuoco e lui si trovava in mezzo alle fiamme; spesso nell’atto di attraversare un fiume, l’acqua si sollevava e minacciava di affogarlo; e di nuovo, ai piedi di una montagna, grosse rocce sembravano rotolare verso di lui come se volessero schiacciare lui e il puledro sotto il loro peso. Sul finire del giorno Peronnik non sapeva se quelle cose fossero state reali o le avesse solo immaginate, ma si tirò giù il berretto fatto a maglia per coprire gli occhi e confidò che il puledro lo portasse sulla strada giusta.

Alla fine si lasciò la foresta alle spalle e si diressero vesto una vasta pianura in cui il vento soffiava forte e freddo. Lo sciocco osò sbirciare fuori e scoprì con sollievo che gli incantesimi sembravano essere finiti sebbene lo scuotesse un brivido di orrore alla vista degli scheletri di uomini sparpagliati sulla pianura, accanto agli scheletri dei loro cavalli. E che cos’erano quelle forme grigie che cavalcavano in lontananza? Erano… sarebbero potuti essere… lupi?

Per quanto la pianura sembrasse vasta, non ci volle molto per attraversarla e ben presto il puledro entrò in una specie di parco ombreggiato in cui si ergeva un solo melo, i cui rami si curvavano a terra per il peso dei frutti. Di fronte vi era il korigan, l’ometto fatato, che teneva in mano la spada fiammeggiante che riduceva in cenere qualunque cosa toccasse. Alla vista di Peronnik gettò un grido acuto e sollevò la spada, ma senza mostrarsi sorpreso il ragazzo si tolse solo il cappello, badando bene di restare a breve distanza.

“Non vi spaventate, mio principe,” disse Peronnik, “Sto proprio andando a Kerglas perché il nobile Rogèar mi ha chiesto di andare da lui per un affare.”

“Ti ha chiesto di andare!” ripeté lo gnomo “E allora, tu chi saresti?”

“Sono il nuovo servitore che ha assunto, come ben sapete.” rispose Peronnik.

“Io non so niente del tutto,” replicò imbronciato il korigan, “per quanto mi riguarda potresti essere un ladro.”

“Mi dispiace,” rispose Peronnik, “ma potrei sbagliarmi nel definirmi un servo perché sono solo un acchiappa-uccelli. Non trattenetemi, vi prego, perché sua altezza il mago mi aspetta e, come potete vedere, mi ha prestato il suo puledro perché possa raggiungere il suo castello il più velocemente possibile.”

A queste parole il korigan posò per la prima volta gli occhi sul puledro, che sapeva essere uno di quelli appartenenti al mago, e cominciò a pensare che il ragazzo stesse dicendo la verità. Dopo aver esaminato il cavallo, esaminò il cavaliere, che aveva un’aria così innocente, e persino assente, da sembrargli incapace di inventare una storia. Tuttavia lo gnomo non era completamente sicuro che andasse tutto bene e chiese che cosa volesse il mago da un acchiappa-uccelli.

“Da quanto ha detto, il precedente era pessimo,” rispose Peronnik “visto che ha affermato che tutti i semi e i frutti del giardino a Kerglas venivano mangiati dagli uccelli.”

“E che cosa intendi fare per fermare ciò, mio buon amico?” chiese il korigan, e Peronnik gli mostrò la trappola che aveva preparato e sottolineò che a nessun uccello sarebbe stato possibile fuggirne.

“È proprio ciò che volevo per esserne sicuro.” rispose il korigan. “Le mie mele sono state mangiate completamente dai merli e dai tordi. Metti la tua trappola e, se riuscirai a prenderli, ti lascerò passare.”

“È un incarico ragionevole” e come ebbe parlato, Peronnik balzò giù e legò il puledro a un albero poi, chinandosi, fissò un’estremità della rete a al tronco del melo e disse al korigan di reggere l’altra mentre lui prendeva i paletti. Lo gnomo fece come gli era stato detto quando improvvisamente Peronnik gli gettò il cappio intorno al collo e lo strinse e ebbe in pugno il korigan in fretta come uno qualsiasi degli uccelli che desiderava intrappolare.

Strillando di rabbia, egli tentò di slacciare la corda, ma riusciva solo a stringere di più il nodo. Aveva adagiato la spada nell’erba e Peronnik stette bene attento a fissare la rete dall’altro lato dell’albero così che ora per lui fu facile staccare una mela e montare a cavallo senza essere intralciato dallo gnomo, che lasciò al suo destino.

Quando si fu lasciato alle spalle la pianura, Peronnik e il suo puledro si ritrovarono in una stretta valle in cui c’era un boschetto di alberi pieni di ogni genere di cose dal dolce profumo – rose di ogni colore, ginestre gialle, caprifogli rosa – mentre sopra tutti essi torreggiava una meravigliosa viola del pensiero scarlatta il cui volto mostrava una strana espressione. Era il fiore che ride e nessuno che lo guardasse poteva fare a meno di ridere anche lui. Il cuore di Peronnik batté forte al pensiero di aver superato sano e salvo la seconda prova e fissò con tutta calma il leone con la criniera di vipere guizzanti che camminava su e giù di fronte al boschetto.

Il ragazzo sollevò il berretto e se lo tolse perché, per quanto fosse sciocco, sapeva che quando hai che fare con qualcuno più grosso di te un berretto è più utile in mano che in testa. Poi, dopo aver augurato ogni genere di cose buone al leone e alla sua famiglia, chiese se fosse sulla strada giusta per Kerglas.

“Che cosa devi fare a Kerglas?” chiese il leone con un ruggito, mostrando i denti.

“Con tutto il rispetto” rispose Peronnik, fingendo di essere molto spaventato “sono il servitore di una dama che è amica del nobile Rogéar e gli manda alcune allodole per farne un pasticcio.”

“Allodole?” gridò il leone, leccandosi i lunghi baffi “Deve essere passato un secolo da quando ne ho avuta qualcuna! Ne hai con te una gran quantità?”

“Quante ne può contenere questo sacco.” rispose Peronnik, aprendo, mentre parlava, il sacco che aveva riempito di piume e di colla; e per dimostrare ciò che aveva detto, volse la schiena al leone e cominciò a imitare il canto di un’allodola.

“Vieni” esclamò il leone, che aveva l’acquolina in bocca “mostrami gli uccelli! Mi piacerebbe vedere se sono abbastanza grassi per il mio padrone.”

“Lo farei con piacere,” rispose lo sciocco “ma se apro una volta il sacco, voleranno via tutti.”

“Beh, apri quanto basta perché vi pssa guardare dentro.” disse il leone, avvicinandosi un po’.

Era proprio ciò che Peronnik aveva sperato facesse, così tenne il sacco mentre il leone lo apriva con cautela e vi metteva dentro la testa, così da poter prendere un bel boccone di allodole. Ma la quantità di piume e di colla lo imprigionò e prima che potesse tirar fuori di nuovo la testa, Peronnik aveva tirato ben bene la corda e fattone un nodo che nessun uomo poteva sciogliere. Poi, cogliendo rapidamente il fiore che ride, galoppò via quanto più velocemente il puledro poté portarlo.

Il sentiero conduceva rapidamente al lago dei draghi che dovette attraversare a nuoto. Il puledro, che vi era abituato, si tuffò in acqua senza esitazione ma, appena i draghi videro Peronnik, si avvicinarono da tutte le parti del lago per divorarlo.

Questa volta Peronnik non si diede pena di levarsi il berretto, ma gettò nell’acqua le perline che aveva portato con sé, come se gettasse mais a un’anatra, e a ogni perlina che un drago inghiottiva, si ribaltava e morì così che lo sciocco raggiunse l’altra riva senza altri problemi.

Ora si stendeva davanti a lui la valle custodita dall’uomo nero e Peronnik lo vide da lontano, incatenato per un piede a una roccia all’ingresso e che reggeva la palla di ferro che non sbagliava mai la mira e tornava sempre nella mano del padrone. In testa l’uomo nero aveva sei occhi che non mai chiusi tutti insieme, ma che montavano la guardia l’uno dopo l’altro. In quel momento erano tutti aperti e Peronnik comprese che se l’uomo nero lo avesse intravisto, avrebbe lanciato la palla. Così, nascondendo il puledro dietro a una macchia di cespugli, strisciò lungo un fosso e si acquattò proprio vicino alla roccia alla quale l’uomo nero era incatenato.

La giornata era calda e dopo un po’ l’uomo cominciò ad avere sonno. Due dei suoi occhi si chiusero e Peronnik cantò dolcemente. In un attimo si chiuse un terzo occhio e Peronnik continuò a cantare. La palpebra di un quarto occhio calò pesantemente e poi quella del quinto e del sesto. l’uomo nero si era del tutto addormentato.

Allora, in punta di piedi, lo sciocco sgusciò all’indietro verso il puledro, che condusse sul soffice muschio oltre l’uomo nero nella valle del piacere, un delizioso giardino pieno di frutti che ti penzolano davanti alla bocca, di fontane dalle quali scorre il vino e di fiori che cantano con delicate vocine. Più in là c’erano tavole apparecchiate con il cibo e ragazze che danzavano sull’erba invitandolo a unirsi a loro.

Peronnik sentì e, capendo a malapena ciò che stesse facendo, condusse il puledro ad andatura lenta. Annusò avidamente il profumo dei piatti e sollevò la testa per vedere meglio le danzatrici. Ancora un istante e si sarebbe fermato del tutto e sarebbe stato perduto, come quelli prima di lui, quando improvvisamente ebbe come una visione della ,coppa d’oro e della lancia di diamante. Estraendo dalla sacca il fischietto, soffiò così forte da coprire i dolci suoni intorno a lui e mangiò ciò che restava del pane con la pancetta per spegnere il desiderio ardente dei frutti magici. Teneva gli occhi fissi sulle orecchie del puledro così da non poter vedere le danzatrici.

In questo modo fu in grado di giungere in fondo al giardino e finalmente vide il castello di Kerglas con il fiume con un solo guado tra di loro. La dama sarebbe stata là, come gli aveva detto il vecchio? Sì, certamente c’era, seduta su una roccia, con un abito di raso nero, e il suo volto aveva il colore di una donna moresca. Lo sciocco cavalcò là e si tolse il berretto più educatamente che mai e chiese se non volesse attraversare il fiume.

“Stavo aspettando che tu venissi ad aiutarmi,” rispose lei, “avvicinati così che io possa salire dietro di te.”

Peronnik fece come lei gli aveva detto e, con l’aiuto del suo braccio, balzò agilmente sul dorso del puledro.

“Sai come uccidere il mago?” chiese la dama, mentre attraversavano il guado.

“Penso che, essendo un mago, sia immortale e che nessuno possa ucciderlo.” rispose Peronnik.

“Convincilo ad assaggiare quella mela e morirà, e se non fosse abbastanza, lo toccherò con un dito perché io sono la Peste.” rispose lei.

“Ma se lo uccido, come potrò prendere senza una chiave la coppa d’oro e la lancia di diamante che sono nascosti in cantina?” replicò Peronnik.

“Il fiore che ride apre tutte le porte e illumina tutte le tenebre.” disse la dama e, mentre parlava, raggiunsero l’altra riva e avanzarono verso il castello.

Di fronte all’entrata c’era una specie di tenda sostenuta da pali e sotto vi era seduto il gigante, che si crogiolava al sole. Appena vide il puledro che portava Peronnik e la dama, sollevò la testa e gridò con voce tonante:

“Chi, se non di certo uno sciocco, cavalcherebbe un puledro di tredici mesi!”

“Il più grande dei maghi, tu hai ragione.” rispose Peronnik.

“E come sei riuscito a catturarlo?” chiese il gigante.

“Ripetendo ciò che avevo appreso da tuo fratello Bryak al margine della foresta,” rispose lo sciocco “ ho solo detto:

Puledro, libero di correre e di mangiare,

galoppa veloce fino a farci incontrare.

ed è venuto subito.”

“Allora conosci mio fratello?” domandò il gigante. “Dimmi perché ti ha mandato qui.”

“Per portarti i due doni che aveva appunto ricevuto dal paese dei Mori:” rispose Peronnik “la mela della delizia e la donna del rispetto. Se mangi la mela, non desidererai altro e se prendi la donna come tua serva non ne desidererai un’altra.”

“Ebbene, dammi la mela e di’ alla donna di scendere.” rispose Rogéar.

Lo sciocco obbedì, ma al primo assaggio della mela il gigante barcollò e appena il lungo dito giallo della donna lo toccò, cadde morto.

Lasciando il mago dove giaceva, Peronnik entrò nel palazzo, portando con sé il fiore che ride. Cinquanta porte si aprirono davanti a lui e alla fine raggiunse una lunga serie di gradini che sembravano condurre nelle viscere della terra. Andò giù finché giunse a una porta d’argento senza spranga o chiave. Allora sollevò in alto il fiore che rise e la porta lentamente oscillò all’indietro, mostrando una profonda caverna che era illuminata a giorno dallo scintillio della coppa d’oro e della lancia di diamante. Lo sciocco corse avanti precipitosamente e si appese la coppa al collo per mezzo della catena che vi era attaccata e prese in mano la lancia. Come l’ebbe fatto, il terreno tremò sotto di lui e il palazzo scomparve con un rombo spaventoso, e Peronnik si ritrovò vicino alla foresta in cui aveva condotto il bestiame a pascolare.

Sebbene stessero calando le tenebre, Peronnik neppure pensò di entrare nella fattoria, ma seguì la strada che conduceva alla corte del duca di Bretagna. Mentre passava per la città di Vannes, si fermò nella bottega di un sarto e comprò un magnifico abito di velluto marrone e un cavallo bianco, che pagò con una manciata dell’oro che aveva preso nel corridoio del castello di Kerglas. Poi prese la strada per la città di Nantes che in quel momento era assediata dai Francesi.

Dopo poca strada, Peronnik si fermò e si guardò attorno. Per miglia all’intorno il paese era spoglio perchè il nemico aveva tagliato ogni albero e bruciato ogni foglia di mais; per quanto sciocco potesse essere, Peronnik fu in grado di comprendere che dietro i cancelli gli uomini stavano morendo di fame. Sta ancora guardando inorridito quando sulle mura comparve un trombettiere il quale, dopo aver fatto uno squillo sonoro, annunciò che il duca avrebbe designato come erede l’uomo che avesse condotto i Francesi fuori del suo paese.

Il trombettiere fece uno squillo ai quattro angoli della città e all’ultimo momento Peronnik, che si era avvicinato al galoppo più che aveva potuto, gli rispose.

“Non hai bisogno di suonare ancora,” disse “perché io stesso libererò la città dai suoi nemici.” E voltandosi verso un soldato che giungeva di corsa, agitando la spada, lo toccò con la lancia magica e lui cadde morto sul posto. Gli uomini che lo stavano seguendo si immobilizzarono, sbalorditi. L’armatura del loro compagno non era stata trapassata, di ciò erano certi, eppure egli era morto come se fosse stato colpito al cuore. Prima che avessero il tempo di riprendersi dallo stupore, Peronnik gridò:

“Vedete come se la passano i mie nemici, ora guardate che cosa posso fare per gli amici.” e smontando da cavallo, posò la coppa d’oro sulla bocca del soldato il quale si alzò meglio di prima. Poi, saltando il fossato con il cavallo, oltrepassò il cancello della città che era stato aperto a sufficienza per per accoglierlo.

Le notizie di tali meraviglie attraversarono in fretta la città e ridiedero animo alla guarnigione, così che si dichiarò in gradio di combattere al comando del giovane straniero. E siccome la coppa riportò in vita tutti i bretoni morti, ben presto Peronnik ebbe un esercito grande abbastanza da mandar via i francesi e mantenere la promessa di liberare il paese.

Quanto alla coppa e alla lancia, nessuno seppe che ne fu, ma qualcuno dice che Bryak il mago fece in modo di rubarli di nuovo e che chiunque desideri possederli deve andarne alla ricerca come fece Peronnik.

Da Racconti bretoni di Charles Émile Souvestre (1806-54) avvocato, giornalista e scrittore francese

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)