The Battle of the Birds

(MP3-28'57'')

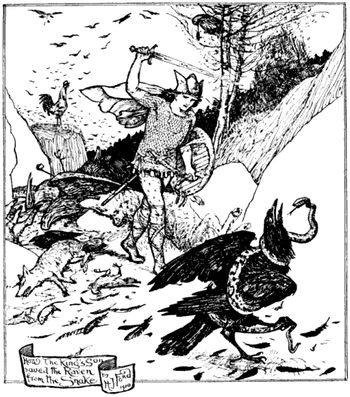

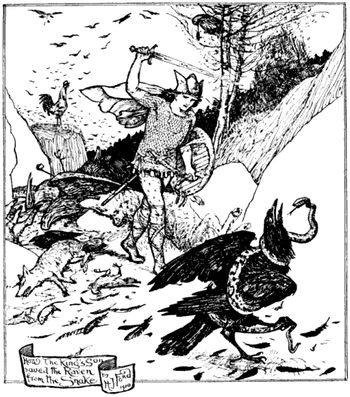

There was to be a great battle between all the creatures of the earth and the birds of the air. News of it went abroad, and the son of the king of Tethertown said that when the battle was fought he would be there to see it, and would bring back word who was to be king. But in spite of that, he was almost too late, and every fight had been fought save the last, which was between a snake and a great black raven. Both struck hard, but in the end the snake proved the stronger, and would have twisted himself round the neck of the raven till he died had not the king’s son drawn his sword, and cut off the head of the snake at a single blow. And when the raven beheld that his enemy was dead, he was grateful, and said:

‘For thy kindness to me this day, I will show thee a sight. So come up now on the root of my two wings.’ The king’s son did as he was bid, and before the raven stopped flying, they had passed over seven bens and seven glens and seven mountain moors.

‘Do you see that house yonder?’ said the raven at last. ‘Go straight for it, for a sister of mine dwells there, and she will make you right welcome. And if she asks, “Wert thou at the battle of the birds?” answer that thou wert, and if she asks, “Didst thou see my likeness?” answer that thou sawest it, but be sure thou meetest me in the morning at this place.’

The king’s son followed what the raven told him and that night he had meat of each meat, and drink of each drink, warm water for his feet, and a soft bed to lie in.

Thus it happened the next day, and the next, but on the fourth meeting, instead of meeting the raven, in his place the king’s son found waiting for him the handsomest youth that ever was seen, with a bundle in his hand.

‘Is there a raven hereabouts?’ asked the king’s son, and the youth answered:

‘I am that raven, and I was delivered by thee from the spells that bound me, and in reward thou wilt get this bundle. Go back by the road thou camest, and lie as before, a night in each house, but be careful not to unloose the bundle till thou art in the place wherein thou wouldst most wish to dwell.’

Then the king’s son set out, and thus it happened as it had happened before, till he entered a thick wood near his father’s house. He had walked a long way and suddenly the bundle seemed to grow heavier; first he put it down under a tree, and next he thought he would look at it.

The string was easy to untie, and the king’s son soon unfastened the bundle. What was it he saw there? Why, a great castle with an orchard all about it, and in the orchard fruit and flowers and birds of very kind. It was all ready for him to dwell in, but instead of being in the midst of the forest, he did wish he had left the bundle unloosed till he had reached the green valley close to his father’s palace. Well, it was no use wishing, and with a sigh he glanced up, and beheld a huge giant coming towards him.

‘Bad is the place where thou hast built thy house, king’s son,’ said the giant.

‘True; it is not here that I wish to be,’ answered the king’s son.

‘What reward wilt thou give me if I put it back in the bundle?’ asked the giant.

‘What reward dost thou ask?’ answered the king’s son.

‘The first boy thou hast when he is seven years old,’ said the giant.

‘If I have a boy thou shalt get him,’ answered the king’s son, and as he spoke the castle and the orchard were tied up in the bundle again.

‘Now take thy road, and I will take mine,’ said the giant. ‘And if thou forgettest thy promise, I will remember it.’

Light of heart the king’s son went on his road, till he came to the green valley near his father’s palace. Slowly he unloosed the bundle, fearing lest he should find nothing but a heap of stones or rags. But no! all was as it had been before, and as he opened the castle door there stood within the most beautiful maiden that ever was seen.

‘Enter, king’s son,’ said she, ‘all is ready, and we will be married at once,’ and so they were.

The maiden proved a good wife, and the king’s son, now himself a king, was so happy that he forgot all about the giant. Seven years and a day had gone by, when one morning, while standing on the ramparts, he beheld the giant striding towards the castle. Then he remembered his promise, and remembered, too, that he had told the queen nothing about it. Now he must tell her, and perhaps she might help him in his trouble.

The queen listened in silence to his tale, and after he had finished, she only said:

‘Leave thou the matter between me and the giant,’ and as she spoke, the giant entered the hall and stood before them.

‘Bring out your son,’ cried he to the king, ‘as you promised me seven years and a day since.’

The king glanced at his wife, who nodded, so he answered:

‘Let his mother first put him in order,’ and the queen left the hall, and took the cook’s son and dressed him in the prince’s clothes, and led him up to the giant, who held his hand, and together they went out along the road. They had not walked far when the giant stopped and stretched out a stick to the boy.

‘If your father had that stick, what would he do with it?’ asked he.

‘If my father had that stick, he would beat the dogs and cats that steal the king’s meat,’ replied the boy.

‘Thou art the cook’s son!’ cried the giant. ‘Go home to thy mother’; and turning his back he strode straight to the castle.

‘If you seek to trick me this time, the highest stone will soon be the lowest,’ said he, and the king and queen trembled, but they could not bear to give up their boy.

‘The butler’s son is the same age as ours,’ whispered the queen; ‘he will not know the difference,’ and she took the child and dressed him in the prince’s clothes, and the giant let him away along the road. Before they had gone far he stopped, and held out a stick.

‘If thy father had that rod, what would he do with it?’ asked the giant.

‘He would beat the dogs and cats that break the king’s glasses,’ answered the boy.

‘Thou art the son of the butler!’ cried the giant. ‘Go home to thy mother’; and turning round he strode back angrily to the castle.

‘Bring out thy son at once,’ roared he, ‘or the stone that is highest will be lowest,’ and this time the real prince was brought.

But though his parents wept bitterly and fancied the child was suffering all kinds of dreadful things, the giant treated him like his own son, though he never allowed him to see his daughters. The boy grew to be a big boy, and one day the giant told him that he would have to amuse himself alone for many hours, as he had a journey to make. So the boy wandered to the top of the castle, where he had never been before. There he paused, for the sound of music broke upon his ears, and opening a door near him, he beheld a girl sitting by the window, holding a harp.

‘Haste and begone, I see the giant close at hand,’ she whispered hurriedly, ‘but when he is asleep, return hither, for I would speak with thee.’ And the prince did as he was bid, and when midnight struck he crept back to the top of the castle.

‘To-morrow,’ said the girl, who was the giant’s daughter, ‘to-morrow thou wilt get the choice of my two sisters to marry, but thou must answer that thou wilt not take either, but only me. This will anger him greatly, for he wishes to betroth me to the son of the king of the Green City, whom I like not at all.’

Then they parted, and on the morrow, as the girl had said, the giant called his three daughters to him, and likewise the young prince to whom he spoke.

‘Now, O son of the king of Tethertown, the time has come for us to part. Choose one of my two elder daughters to wife, and thou shalt take her to your father’s house the day after the wedding.’

‘Give me the youngest instead,’ replied the youth, and the giant’s face darkened as he heard him.

‘Three things must thou do first,’ said he.

‘Say on, I will do them,’ replied the prince, and the giant left the house, and bade him follow to the byre, where the cows were kept.

‘For a hundred years no man has swept this byre,’ said the giant, ‘but if by nightfall, when I reach home, thou has not cleaned it so that a golden apple can roll through it from end to end, thy blood shall pay for it.’

All day long the youth toiled, but he might as well have tried to empty the ocean. At length, when he was so tired he could hardly move, the giant’s youngest daughter stood in the doorway.

‘Lay down thy weariness,’ said she, and the king’s son, thinking he could only die once, sank on the floor at her bidding, and fell sound asleep. When he woke the girl had disappeared, and the byre was so clean that a golden apple could roll from end to end of it. He jumped up in surprise, and at that moment in came the giant.

‘Hast thou cleaned the byre, king’s son?’ asked he.

‘I have cleaned it,’ answered he.

‘Well, since thou wert so active to-day, to-morrow thou wilt thatch this byre with a feather from every different bird, or else thy blood shall pay for it,’ and he went out.

Before the sun was up, the youth took his bow and his quiver and set off to kill the birds. Off to the moor he went, but never a bird was to be seen that day. At last he got so tired with running to and fro that he gave up heart.

‘There is but one death I can die,’ thought he. Then at midday came the giant’s daughter.

‘Thou art tired, king’s son?’ asked she.

‘I am,’ answered he; ‘all these hours have I wandered, and there fell but these two blackbirds, both of one colour.’

‘Lay down thy weariness on the grass,’ said she, and he did as she bade him, and fell fast asleep.

When he woke the girl had disappeared, and he got up, and returned to the byre. As he drew near, he rubbed his eyes hard, thinking he was dreaming, for there it was, beautifully thatched, just as the giant had wished. At the door of the house he met the giant.

‘Hast thou thatched the byre, king’s son?’

‘I have thatched it.’

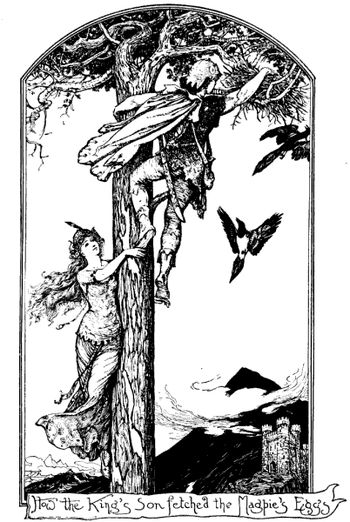

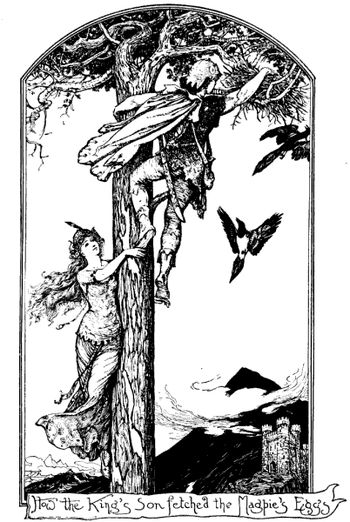

‘Well, since thou hast been so active to-day, I have something else for thee! Beside the loch thou seest over yonder there grows a fir tree. On the top of the fir tree is a magpie’s nest, and in the nest are five eggs. Thou wilt bring me those eggs for breakfast, and if one is cracked or broken, thy blood shall pay for it.’

Before it was light next day, the king’s son jumped out of bed and ran down to the loch. The tree was not hard to find, for the rising sun shone red on the trunk, which was five hundred feet from the ground to its first branch. Time after time he walked round it, trying to find some knots, however small, where he could put his feet, but the bark was quite smooth, and he soon saw that if he was to reach the top at all, it must be by climbing up with his knees like a sailor. But then he was a king’s son and not a sailor, which made all the difference.

However, it was no use standing there staring at the fir, at least he must try to do his best, and try he did till his hands and knees were sore, for as soon as he had struggled up a few feet, he slid back again. Once he climbed a little higher than before, and hope rose in his heart, then down he came with such force that his hands and knees smarted worse than ever.

‘This is no time for stopping,’ said the voice of the giant’s daughter, as he leant against the trunk to recover his breath.

‘Alas! I am no sooner up than down,’ answered he.

‘Try once more,’ said she, and she laid a finger against the tree and bade him put his foot on it. Then she placed another finger a little higher up, and so on till he reached the top, where the magpie had built her nest.

‘Make haste now with the nest,’ she cried, ‘for my father’s breath is burning my back,’ and down he scrambled as fast as he could, but the girl’s little finger had caught in a branch at the top, and she was obliged to leave it there. But she was too busy to pay heed to this, for the sun was getting high over the hills.

‘Listen to me,’ she said. ‘This night my two sisters and I will be dressed in the same garments, and you will not know me. But when my father says ‘Go to thy wife, king’s son,’ come to the one whose right hand has no little finger.’

So he went and gave the eggs to the giant, who nodded his head.

‘Make ready for thy marriage,’ cried he, ‘for the wedding shall take place this very night, and I will summon thy bride to greet thee.’ Then his three daughters were sent for, and they all entered dressed in green silk of the same fashion, and with golden circlets round their heads. The king’s son looked from one to another. Which was the youngest? Suddenly his eyes fell on the hand of the middle one, and there was no little finger.

‘Thou hast aimed well this time too,’ said the giant, as the king’s son laid his hand on her shoulder, ‘but perhaps we may meet some other way’; and though he pretended to laugh, the bride saw a gleam in his eye which warned her of danger.

The wedding took place that very night, and the hall was filled with giants and gentlemen, and they danced till the house shook from top to bottom. At last everyone grew tired, and the guests went away, and the king’s son and his bride were left alone.

‘If we stay here till dawn my father will kill thee,’ she whispered, ‘but thou art my husband and I will save thee, as I did before,’ and she cut an apple into nine pieces, and put two pieces at the head of the bed, and two pieces at the foot, and two pieces at the door of the kitchen, and two at the big door, and one outside the house. And when this was done, and she heard the giant snoring, she and the king’s son crept out softly and stole across to the stable, where she led out the blue-grey mare and jumped on its back, and her husband mounted behind her. Not long after, the giant awoke.

‘Are you asleep?’ asked he.

‘Not yet,’ ‘Not yet,’ answered the apple at the head of the bed, and the giant turned over, and soon was snoring as loudly as before. By and bye he called again.

‘Are you asleep?’

‘Not yet,’ said the apple at the foot of the bed, and the giant was satisfied. After a while, he called a third time, ‘Are you asleep?’

‘Not yet,’ replied the apple in the kitchen, but when in a few minutes, he put the question for the fourth time and received an answer from the apple outside the house door, he guessed what had happened, and ran to the room to look for himself.

The bed was cold and empty!

‘My father’s breath is burning my back,’ cried the girl, ‘put thy hand into the ear of the mare, and whatever thou findest there, throw it behind thee.’ And in the mare’s ear there was a twig of sloe tree, and as he threw it behind him there sprung up twenty miles of thornwood so thick that scarce a weasel could go through it. And the giant, who was striding headlong forwards, got caught in it, and it pulled his hair and beard.

‘This is one of my daughter’s tricks,’ he said to himself, ‘but if I had my big axe and my wood-knife, I would not be long making a way through this,’ and off he went home and brought back the axe and the wood-knife.

It took him but a short time to cut a road through the blackthorn, and then he laid the axe and the knife under a tree.

‘I will leave them there till I return,’ he murmured to himself, but a hoodie crow, which was sitting on a branch above, heard him.

‘If thou leavest them,’ said the hoodie, ‘we will steal them.’

‘You will,’ answered the giant, ‘and I must take them home.’ So he took them home, and started afresh on his journey.

‘My father’s breath is burning my back,’ cried the girl at midday. ‘Put thy finger in the mare’s ear and throw behind thee whatever thou findest in it,’ and the king’s son found a splinter of grey stone, and threw it behind him, and in a twinkling twenty miles of solid rock lay between them and the giant.

‘My daughter’s tricks are the hardest things that ever met me,’ said the giant, ‘but if I had my lever and my crowbar, I would not be long in making my way through this rock also,’ but as he had got them, he had to go home and fetch them. Then it took him but a short time to hew his way through the rock.

‘I will leave the tools here,’ he murmured aloud when he had finished.

‘If thou leavest them, we will steal them,’ said a hoodie who was perched on a stone above him, and the giant answered:

‘Steal them if thou wilt; there is no time to go back.’

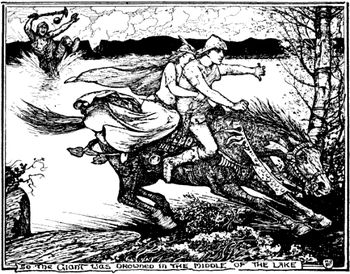

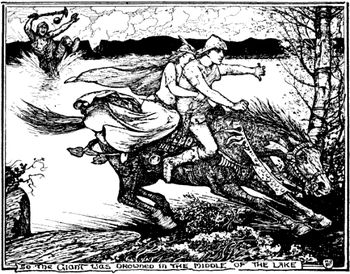

‘My father’s breath is burning my back,’ cried the girl; ‘look in the mare’s ear, king’s son, or we are lost,’ and he looked, and found a tiny bladder full of water, which he threw behind him, and it became a great lock. And the giant, who was striding on so fast, could not stop himself, and he walked right into the middle and was drowned.

The blue-grey mare galloped on like the wind, and the next day the king’s son came in sight of his father’s house.

‘Get down and go in,’ said the bride, ‘and tell them that thou hast married me. But take heed that neither man nor beast kiss thee, for then thou wilt cease to remember me at all.’

‘I will do thy bidding,’ answered he, and left her at the gate. All who met him bade him welcome, and he charged his father and mother not to kiss him, but as he greeted them his old greyhound leapt on his neck, and kissed him on the mouth. And after that he did not remember the giant’s daughter.

All that day she sat on a well which was near the gate, waiting, waiting, but the king’s son never came. In the darkness she climbed up into an oak tree that shadowed the well, and there she lay all night, waiting, waiting.

On the morrow, at midday, the wife of a shoemaker who dwelt near the well went to draw water for her husband to drink, and she saw the shadow of the girl in the tree, and thought it was her own shadow.

‘How handsome I am, to be sure,’ said she, gazing into the well, and as she stopped to behold herself better, the jug struck against the stones and broke in pieces, and she was forced to return to her husband without the water, and this angered him.

‘Thou hast turned crazy,’ said he in wrath. ‘Go thou, my daughter, and fetch me a drink,’ and the girl went, and the same thing befell her as had befallen her mother.

‘Where is the water?’ asked the shoemaker, when she came back, and as she held nothing save the handle of the jug he went to the well himself. He too saw the reflection of the woman in the tree, but looked up to discover whence it came, and there above him sat the most beautiful woman in the world.

‘Come down,’ he said, ‘for a while thou canst stay in my house,’ and glad enough the girl was to come.

Now the king of the country was about to marry, and the young men about the court thronged the shoemaker’s shop to buy fine shoes to wear at the wedding.

‘Thou hast a pretty daughter,’ said they when they beheld the girl sitting at work.

‘Pretty she is,’ answered the shoemaker, ‘but no daughter of mine.’

‘I would give a hundred pounds to marry her,’ said one.

‘And I,’ ‘And I,’ cried the others.

‘That is no business of mine,’ answered the shoemaker, and the young men bade him ask her if she would choose one of them for a husband, and to tell them on the morrow. Then the shoemaker asked her, and the girl said that she would marry the one who would bring his purse with him. So the shoemaker hurried to the youth who had first spoken, and he came back, and after giving the shoemaker a hundred pounds for his news, he sought the girl, who was waiting for him.

‘Is it thou?’ inquired she. ‘I am thirsty, give me a drink from the well that is yonder.’ And he poured out the water, but he could not move from the place where he was; and there he stayed till many hours had passed by.

‘Take away that foolish boy,’ cried the girl to the shoemaker at last, ‘I am tired of him,’ and then suddenly he was able to walk, and betook himself to his home, but he did not tell the others what had happened to him.

Next day there arrived one of the other young men, and in the evening, when the shoemaker had gone out and they were alone, she said to him, ‘See if the latch is on the door.’ The young man hastened to do her bidding, but as soon as he touched the latch, his fingers stuck to it, and there he had to stay for many hours, till the shoemaker came back, and the girl let him go. Hanging his head, he went home, but he told no one what had befallen him.

Then was the turn of the third man, and his foot remained fastened to the floor, till the girl unloosed it. And thankfully, he ran off, and was not seen looking behind him.

‘Take the purse of gold,’ said the girl to the shoemaker, ‘I have no need of it, and it will better thee.’ And the shoemaker took it and told the girl he must carry the shoes for the wedding up to the castle.

‘I would fain get a sight of the king’s son before he marries,’ sighed she.

‘Come with me, then,’ answered he; ‘the servants are all my friends, and they will let you stand in the passage down which the king’s son will pass, and all the company too.’

Up they went to the castle, and when the young men saw the girl standing there, they led her into the hall where the banquet was laid out and poured her out some wine. She was just raising the glass to drink when a flame went up out of it, and out of the flame sprang two pigeons, one of gold and one of silver. They flew round and round the head of the girl, when three grains of barley fell on the floor, and the silver pigeon dived down, and swallowed them.

‘If thou hadst remembered how I cleaned the byre, thou wouldst have given me my share,’ cooed the golden pigeon, and as he spoke three more grains fell, and the silver pigeon ate them as before.

‘If thou hadst remembered how I thatched the byre, thou wouldst have given me my share,’ cooed the golden pigeon again; and as he spoke three more grains fell, and for the third time they were eaten by the silver pigeon.

‘If thou hadst remembered how I got the magpie’s nest, thou wouldst have given me my share,’ cooed the golden pigeon.

Then the king’s son understood that they had come to remind him of what he had forgotten, and his lost memory came back, and he knew his wife, and kissed her. But as the preparations had been made, it seemed a pity to waste them, so they were married a second time, and sat down to the wedding feast.

From Tales of the West Highlands.

La battaglia degli uccelli

Ci sarebbe stata una grande battaglia tra tutte le creature della terra e gli uccelli dell’aria. La notizia si diffuse e il figlio del re di Tethertown disse che, quando fosse stata combattuta, sarebbe stato là a vederla e avrebbe riportato indietro la notizia di chi fosse diventato re. Ma nonostante ciò, fece troppo tardi e tutte le battaglie erano state combattute tranne l’ultima, quella tra un serpente e un grosso corvo nero. Lottarono entrambi duramente, ma alla fine il serpente si mostrò il più forte e si sarebbe avvolto intorno al collo del corvo finché fosse morto se il figlio del re non avesse sguainato la spada e tagliato la testa del serpente con un sol colpo. Quando il corvo vide che il nemico era morto, fu riconoscente e disse:

“Per la tua gentilezza verso di me in questo giorno, ti farò vedere qualcosa. Così salì all’attaccatura delle mie ali.” Il figlio del re fece come gli era stato detto e prima che il corvo finisse di volare erano passati su sette cime, sette valli e sette brughiere montane.

“Vedi quella casa laggiù?” disse alla fine il corvo. “Dirigiti là perché una delle mie sorelle vi dimora e ti darà il benvenuto. E se chiede ‘Sei stato alla battaglia degli uccelli?’ rispondi che ci sei stato, e se chiede ‘Hai visto qualcuno simile a me?’ rispondi che l’hai visto, ma bada bene di incontrarmi domattina in questo posto.”

Il figlio de re fece come gli aveva detto il corvo e quella notte ebbe carne di ogni carne, bevanda di ogni bevanda, acqua calda per i piedi e un letto soffice per giacere.

Ciò accadde il giorno seguente, e anche il successivo, ma la quarta mattina, invece di incontrare il corvo, al suo posto il figlio del re trovò ad attenderlo il più bel ragazzo che avesse mai visto, con un involto in mano.

“C’è un corvo nero da queste parti?” chiese il figlio del re, e il ragazzo rispose:

“Il corvo sono io e sono stato liberato da te dall’incantesimo che mi imprigionava; come ricompensa prendi questo involto. Torna indietro sulla strada da cui sei venuto e riposati come hai fatto prima, una notte in ciascuna casa, ma bada bene di non aprire l’involto finché non sarai nel luogo in cui più desideri stare.”

Allora il figlio de re se ne andò e tutto accadde come era accaduto in precedenza finché entro in un fitto bosco vicino alla casa di suo padre. Aveva percorso molta strada e improvvisamente l’involto sembrò diventare più pesante; dapprima lo pose a terra sotto un albero e poi pensò che gli avrebbe dato un’occhiata.

La corda era facile da sciogliere e il figlio del re ben presto disfece l’involto. Che cosa vi vide? Ebbene, un grande castello con un frutteto tutto intorno, e nel frutteto frutti, fiori e uccelli di ogni tipo. Era tutto pronto perché lui vi abitasse, ma invece che nel mezzo della foresta, desiderò di aver lasciato chiuso l’involto finché non avesse raggiunto la verde vallata presso il palazzo di suo padre. Ebbene, fu vano desiderarlo, e con un sospiro dette un occhiata in su e vide un enorme gigante venire verso di lui.

“Brutto posto dove vuoi costruire la tua casa, figlio del re.” disse il gigante.

“È vero, non è qui che vorrei fosse.” rispose il figlio del re.

“Che ricompensa mi darai se la rimetto nell’involto?” chiese il gigante.

“Che ricompensa chiedi?” rispose il figlio del re.

“Il tuo primo figlio quando avrà sette anni.” disse il gigante.

“Se avrò un figlio, potrai prenderlo.” rispose il figlio del re e, mentre parlava, il castello e il frutteto furono di nuovo richiusi nell’involto.

“Ora prendi la tua strada e io prenderò la mia,” disse il gigante, “ e se dimenticherai la tua promessa, la rammenterò io.”

Il figlio del re riprese la strada con il cuore leggero finché giunse alla verde vallata vicino al palazzo di suo padre. Lentamente aprì l’involto, temendo che in fine non vi avrebbe trovato niente altro che un mucchio di pietre o di stracci. Ma no! Era tutto come prima e, quando aprì la porta del castello, lì c’era la più bella fanciulla che avesse mai visto.

“Entra, figlio de re,” disse lei, “è tutto pronto e noi ci sposeremo subito.” e così fu.

La fanciulla si dimostrò una buona moglie e il figlio del re, ora re lui stesso, era così felice che dimenticò del tutto il gigante. Erano trascorsi sette anni e un giorno quando una mattina, mentre si trovava sui bastioni, vide il gigante venire a grandi passi verso il castello. Allora rammentò la promessa e anche di non averne mai parlato con la regina. Adesso glielo doveva dire e forse lei lo avrebbe potuto aiutarlo in quel guaio.

La regina ascoltò in silenzio il racconto e, dopo che lui ebbe finito, disse solo:

“Lascia che me la veda io con il gigante.” e aveva appena parlato che il gigante entrò nella sala e si mise davanti a loro.

“Portate vostro figlio,” gridò al re, “me lo avevi promesso sette anni e un giorno fa.”

Il re gettò un’occhiata alla moglie, che scrollò la testa, così rispose:

“Lascia che sua madre lo metta in ordine.” e la regina lasciò la sala e prese il figlio del cuoco, gli fece indossare gli abiti del principe e lo condusse dal gigante, che lo prese per mano e se ne andarono insieme lungo la strada. Non avevano camminato molto quando il gigante si fermò e porse un bastoncino al bambino.

“Se tuo padre avesse questo bastoncino, che cosa ci farebbe?” chiese.

“Se mio padre avesse quel bastoncino, picchierebbe i cani e i gatti che rubano la carne del re.” rispose il bambino.

“Tu sei il figlio del cuoco!” gridò il gigante. “Torna a casa da tua madre.” e, voltandogli le spalle, andò difilato al castello.

“Se questa volta mi giocate un brutto tiro, la pietre più alta diventerà presto la più bassa.” disse, e il re e la regina tremarono, ma non osavano dargli il loro bambino.

“il figlio del maggiordomo ha la medesima età del nostro,” sussurrò la regina, non capirà la differenza. “ e prese il bambino, lo vestì con gli abiti del principe e il gigante lo portò via lungo la strada. Prima che fossero giunti lontano, si fermò e tirò fuori il bastoncino.

“Se tuo padre avesse questo bastoncino, che cosa ne farebbe?” chiese il gigante.

“Picchierebbe i cani e i gatti che rompono i cristalli del re.” rispose il bambino.

“Tu sei il figlio del maggiordomo!” strillò il gigante. “Vai a casa da tua madre.” e, girandosi, tornò rabbiosamente a lunghi passi al castello.

“Portate subito vostro figlio,” ruggì, “o la pietra più alta diventerà la più bassa.” e stavolta fu condotto il vero principe.

Sebbene i suoi genitori avessero pianto amaramente e immaginato che il bambino soffrisse ogni genere di cose spaventose, il gigante lo trattava come un figlio, sebbene non gli permettesse mai di vedere le sue figlie. Il bambino crebbe e diventò un ragazzone e un giorno il gigante gli disse che si sarebbe potuto svagare da solo per alcune ore perché lui doveva compiere un viaggio. Così il ragazzo andò sulla sommità del castello, dove non era mai stato prima.

Lì si arrestò perché un suono di musica gli colpì le orecchie e, aprendo una porta vicina a lui, vide una ragazza seduta alla finestra che stava suonando un’arpa.

“Sbrigati ad andartene, vedo il gigante nelle vicinanze,” sussurrò frettolosamente, “ma quando dormirà, torna qui perché vorrei parlare con te.” e il principe fece come gli era stato detto e, quando batté la mezzanotte, sgusciò fino alla sommità del castello.

“Domani” disse la ragazza, che era la figlia del gigante, “domani ti sarà data la scelta di sposare una delle mie due sorelle, ma devi rispondere che non vuoi prendere nessuna delle due, ma solo me. Ciò lo farà arrabbiare enormemente perché desidera promettermi in matrimonio al figlio del re della Città Verde, che non mi piace per niente.”

Poi si separarono e l’indomani, come aveva detto la ragazza, il gigante chiamò le tre figlie e anche il giovane principe, al quale parlò.

“Adesso, o figlio de re di Tethertown, è venuto il momento di separarci. Scegli come moglie una delle mie due figlie maggiori e portala a casa di tuo padre il giorno dopo le nozze.”

“Dammi invece la tua figlia minore,” rispose il ragazzo, e il viso del gigante si oscurò nel sentirlo.

“Prima dovrai fare tre cose.” disse.

“Dille, e le farò,” replicò il principe e il gigante lasciò la casa e gli ordinò di proseguire per la stalla in cui erano tenute le mucche.

“Per cento anni nessun uomo ha pulito questa stalla;2 disse il gigante, “ma se al termine della notte, quando sarò tornato a casa, tu non l’avrai pulita talmente che una mela d’oro vi possa rotolare dall’inizio alla fine, il tuo sangue pagherà per questo.”

Il ragazzo fece pulizia per tutto il giorno, ma era come tentare di svuotare l’oceano. Alla fine quando fu così stanco che malapena poteva muoversi, la figlia minore del gigante comparve sulla soglia.

“Abbandona la stanchezza.” disse, e il figlio del re, pensando che sarebbe morto una volta sola, si lasciò cadere a terra alle sue parole e si addormentò profondamente. Quando si svegliò, la ragazza era sparita e la stalla era così pulita che una mela d’oro avrebbe potuto rotolarvi dall’inizio alla fine. Balzò in piedi sorpreso e in quel momento giunse il gigante.

“Hai pulito la stalla, figlio del re?” chiese.

“L’ho pulita.” rispose lui.

“Ebbene, visto che sei stato così operoso oggi, domani ricoprirai questa stalla con una piuma di ogni tipo di uccello altrimenti il tuo sangue pagherà per questo.” e se ne andò.

Prima che il sole si levasse, il ragazzo prese l’arco e la faretra e partì per uccidere gli uccelli. Andò nella brughiera, ma quel giorno non si vide neppure un uccello. Alla fine si sentì così stanco per aver corso qua e là che gli cedette.

‘C’è una sola morte di cui posso morire.’ pensò. Poi a mezzogiorno venne la figlia del gigante. “Sei stanco, figlio del re?” gli chiese.

“Lo sono,” rispose lui, “ho vagato per tutte queste ore e non ho abbattuto che due merli, entrambi di un solo colore.”

“Abbandona la stanchezza nell’erba.” disse la ragazza, e lui fece come gli era stato detto e cadde addormentato.

Quando si svegliò, la ragazza era sparita; si alzò e tornò alla stalla. Quando fu vicino, si stropicciò forte gli occhi, pensando di sognare, perché era meravigliosamente ricoperta proprio come aveva desiderato il gigante. Sulla porta di casa incontrò il gigante.

“Hai ricoperto la stalla, figlio del re?”

“L’ho ricoperta.”

“Ebbene, siccome oggi sei stato così operoso, ho qualcos’altro per te! Accanto al lago che vedi laggiù cresce un abete. Sulla cima dell’abete c’è un nido di gazza e nel nido ci sono cinque uova. Portami quelle uova per colazione e se una si incrina o si rompe, il tuo sangue pagherà per questo.”

Prima che sorgesse il giorno successivo, il figlio del re balzò giù dal letto e corse al lago. L’albero non fu difficile da trovare perché il sole nascente brillava rosso sul tronco, che era alto cinquecento piedi dal terreno ai rami estremi. Più volte gli girò intorno, cercando di trovare qualche nodo, per quanto piccolo, su cui potesse appoggiare il piede, ma la corteccia era completamente liscia e ben presto vide che, se voleva proprio raggiungere la cima, si sarebbe dovuto arrampicare con le ginocchia come un marinaio. Ma lui era un figlio di re e non un marinaio, il che faceva tutta la differenza.

In ogni modo siccome non serviva a niente star lì a fissare l’abete, alla fine cercò di fare del proprio meglio e tentò finché le mani e le ginocchia furono scorticate perché appena si era fatto strada con un piede, scivolava di nuovo indietro. Una volta si arrampicò un poco più in alto di prima e la speranza gli si riaccese in cuore, poi venne giù con tale forza che le mani e le ginocchia gli bruciarono peggio che mai.

“Non è tempo di fermarsi.” disse la voce della figlia del gigante, appena lui si appoggiò al tronco per riprendere fiato.

“Ahimè, non sono più veloce a salire quanto a scendere.” rispose lui.

“Tenta ancora una volta.” disse lei e puntò un dito contro l’albero e gli disse di salirci con il piede. Poi puntò un altro dito un po’ più in alto e così fece finché egli raggiunse la cima sulla quale la gazza aveva costruito il nido.

“Sbrigati con il nido,” gridò la ragazza, “perché il respiro di mio padre mi sta bruciando la schiena.” e lui scese carponi più in fretta che poté, ma il mignolo della ragazza rimase impigliato in un ramo in cima e lei fu costretta a lasciarlo lì. Ma era troppo occupata per badarvi perché il sole stava calando dietro le colline.

“Ascoltami.” gli disse. “Stanotte le mie due sorelle e io indosseremo i medesimi abiti e tu non mi riconoscerai. Ma quando mio padre dirà: ‘Vai da tua moglie, figlio del re.” vai da quella la cui mano destra non avrà il mignolo.

Così lui andò e diede le uova al gigante, che accennò di sì con la testa.

“Preparati per il matrimonio,” gridò il gigante, “perché le nozze avranno luogo proprio stanotte e io ordinerò alla tua sposa di accoglierti.” Poi furono mandate a chiamare le tre sorelle ed entrarono vestite di seta verde nella medesima foggia con cerchietti d’oro intorno alle teste. Il figlio del re le guardò dall’una all’altra. Qual era la più giovane? Improvvisamente lo sguardo gli cadde sulla mano di quella al centro e non c’era il mignolo.

“Hai mirato bene anche stavolta,” disse il gigante, quando il figlio del re le posò la mano sulla spalla, “ma forse potremo incontrarci in altro modo.” e sebbene fingesse di ridere, la sposa vide un luccichio nel suo occhio che l’avvertiva del pericolo.

Le nozze ebbero luogo proprio quella notte e la sala era piena di giganti e di gentiluomini e danzarono finché la casa tremò da cima a fondo. Alla fine tutti furono stanchi, gli ospiti andarono via e il figlio del re e la sua sposa furono lasciati soli.

“Se resteremo qui fino all’alba, mio padre ti ucciderà,” sussurrò, “ma tu sei mio marito e io ti salverò, come ho fatto in precedenza.” e tagliò una mela in nove pezzi, mise due pezzi alla testa del letto, due pezzi ai piedi, due pezzi alla porta della cucina, due alla porta principale e uno fuori di casa. Quando ciò fu fatto e udì il gigante russare, lei e il figlio del re scivolarono fuori silenziosamente e si avvicinarono furtivi alla stalla dove lei tirò fuori la giumenta grigio-blu, le balzò in groppa e il marito salì dietro di lei. Poco più tardi il gigante si svegliò.

“State dormendo?” chiese.

“Non ancora.” rispose la mela a capo del letto e il gigante si voltò e ben presto russava sonoramente come prima. Di lì a poco chiamò di nuovo.

“State dormendo?”

“Non ancora.” disse la mela ai piedi del letto e il gigante fu soddisfatto. Dopo un po’ chiamò per la terza volta. “State dormendo?”

“Non ancora.” rispose la mela in cucina ma quando pochi minuti dopo pose la domanda per la quarta volta e ricevette una risposta dalla mela fuori della porta, intuì che qualcosa stava accadendo e corse nella stanza per vedere da sé.

Il letto era freddo e vuoto!

“Il respiro di mio padre mi sta bruciando la schiena,” gridò la ragazza, “metti la mano nell’orecchio della puledra e qualsiasi cosa trovi, gettala dietro di te.” e nell’orecchio della puledra c’era un ramoscello di prugno selvatico e come l’ebbe gettato alle spalle, spuntarono venti miglia di bosco di biancospini così fitto che a malapena vi sarebbe passata attraverso una donnola. E il gigante, che stava avanzando a grandi passi a testa bassa, vi rimase preso e gli strappò capelli e barba.

‘Questo è uno dei trucchi di mia figlia’ si disse, ‘ ma se avessi con me l’ascia e il coltello, mi potrei fare strada attraverso il bosco.’ e tornò a casa e prese l’ascia e il coltello.

Gli occorse poco tempo per aprirsi un varco nel bosco di biancospini e poi depose l’ascia e il coltello sotto un albero.

‘Li lascerò fino al mio ritorno’ mormorò tra sé, ma una cornacchia grigia, che era appollaiata su un ramo lì sopra, lo sentì.

“Se li lasci lì,” disse la cornacchia grigia, “li ruberemo.”

“Lo fareste,” rispose il gigante, “ e devo portarli a casa.” così li portò a casa e poi riprese il viaggio.

“Il respiro di mio padre mi sta bruciando la schiena,” gridò a mezzogiorno la ragazza. “metti le dita nell’orecchio della puledra e getta dietro di te qualsiasi cosa vi trovi.” e il figlio del re trovò una scheggia di pietra grigia, la gettò dietro di sé e in un batter d’occhio venti miglia di di solida roccia si stesero tra loro e il gigante.

“I trucchi di mia figlia sono le cose più difficili che mi siano capitate,” disse il gigante, “ ma se avessi la mia leva e il mio palanchino non mi ci vorrebbe molto per farmi strada anche attraverso questa roccia.” Siccome non li aveva, dovette tornare a casa a prenderli. Gli ci volle poco tempo per aprirsi un varco nella roccia.

“Lascerò qui gli attrezzi.” mormorò quando ebbe finito.

“Se li lasci, li ruberemo.” disse una gazza grigia che era appollaiata su una pietra in alto e il gigante rispose:

“Rubateli pure, se volete; non c’è tempo per tornare indietro.”

“Il respiro di mio padre mi sta bruciando la schiena,” gridò la ragazza, “guarda nell’orecchio della puledra, figlio del re, o saremo perduti.” Lui guardò e trovò una piccola vescica piena d’acqua, che gettò dietro di sé e diventò un grande lago. E il gigante, che stava avanzando così veloce a grandi passi, non poté fermarsi e vi finì dritto in mezzo e annegò.

La puledra grigio-blu galoppava come il vento e il giorno seguente il figlio del re giunse in vista della casa del padre.

“Smonta e vai,” disse la sposa, “ e di’ loro che mi hai sposata. Ma bada che né un uomo né un animale ti bacino perché allora smetterai del tutto di ricordarti di me.”

“Farò come dici.” rispose lui e la lasciò al cancello. Tutti quelli che lo incontravano gli davano il benvenuto e chiese al padre e alla madre di non baciarlo, ma mentre li salutava, il suo vecchio levriero gli saltò alle ginocchia e lo baciò sulla bocca. Dopodiché non si rammentò più della figlia del gigante.

Lei rimase seduta tutto il giorno sul pozzo vicino al cancello, in attesa, ma il figlio del re non tornava mai. Quando fu buio si arrampicò sulla quercia che ombreggiava il muro e li si sdraiò per la notte, in attesa.

La mattina, a mezzogiorno, la moglie del calzolaio, che abitava vicino al pozzo, venne a prendere l’acqua da far bere al marito e vide l’ombra della ragazza sull’albero e pensò che fosse la propria.

“Come sono bella, di certo.” disse, rimirandosi nel pozzo e, siccome si fermò per guardarsi meglio, la brocca sbatté contro le pietre e andò in pezzi così fu costretta a tornare dal marito senza l’acqua e ciò lo fece arrabbiare.

“Sei impazzita,” disse incollerito. “Figlia mia, vai tu a prendermi da bere.” e la ragazza andò e le accadde la medesima cosa che era accaduta alla madre.

“Dov’è l’acqua?” chiese il calzolaio quando tornò, ma siccome non aveva niente salvo il manico della brocca, andò al pozzo lui stesso. Anche lui vide il riflesso della donna sull’albero, ma guardò su per scoprire da dove venisse e sopra di lui sedeva la donna più bella del mondo.

“Scendi,” disse, le disse, “puoi stare per un po’ a casa mia.” e la ragazza fu contenta di venirci.

Il re del paese stava per sposarsi e i giovani di corte affollavano la bottega del calzolaio per comperare scarpe eleganti da indossare alle nozze.

“Hai una bella figlia.” dissero, quando videro la ragazza seduta al lavoro.

“È bella,” rispose il calzolaio, “ma non è mia figlia.”

“Darei cento sterline per sposarla.” disse uno.

“Anche io! Anche io!” gridarono gli altri

“Non è affar mio,” rispose il calzolaio e i giovani gli dissero di chiederle se avesse voluto scegliere uno di loro come marito e di dirlo loro l’indomani. Allora il calzolaio glielo chiese e la ragazza disse che avrebbe sposato colui che avesse portato con sé la borsa. Così il calzolaio andò in fretta dal giovane che aveva parlato per primo e lui tornò indietro e, dopo aver dato al calzolaio le cento sterline per le sue notizie, andò in cerca della ragazza, che lo stava spettando.

“Sei tu?” gli chiese. “Ho sete, portami da bere dal pozzo che è laggiù.” lui attinse l’acqua, ma non poté muoversi dal posto in cui era e l’ rimase finché furono trascorse un po’ di ore.

“Porta via quel ragazzo sciocco.” gridò infine la ragazza al calzolaio. “Sono stanca di lui.” e allora improvvisamente lui fu in grado di camminare e tornò a casa, ma non disse agli altri ciò che gli era accaduto.

Il giorno seguente arrivò un altro dei giovanotti e la sera, quando il calzolaio fu andato via e rimasero soli, la ragazza gli disse: “Guarda se c’è il chiavistello alla porta.” Il ragazzo si affrettò a fare ciò che gli era stato detto, ma appena toccò il chiavistello, le sue dita rimasero attaccate e l’ rimase per molte ore finché tornò il calzolaio e la ragazza lo mandò via. Chinando la testa, tornò a casa, ma non disse a nessuno ciò che gli era capitato.

Poi fu il turno del terzo uomo e i suoi piedi rimasero incollati al pavimento finché la ragazza non lo liberò. Grato, corse via e non lo si vide guardare indietro.

“Prendi la borsa dell’oro.” disse la ragazza al calzolaio. “Io non ne ho bisogno e sarà più utile a te.” e il calzolaio la prese e disse alla ragazza che doveva portare al castello le scarpe per il matrimonio.

“Mi piacerebbe dare un’occhiata al figlio del re prima che si sposi.” sospirò la ragazza.

“Vieni con me, allora,” disse il calzolaio, “i servitori sono tutti amici miei e ti permetteranno di stare nel corridoio nel quale passeranno il figlio del re e anche tutto il seguito.”

Andarono al castello e quando i giovanotti videro la ragazza che stava lì, la condussero nella sala in cui era allestito il banchetto e le versarono un po’ di vino. Stava sollevando il calice per bere quando ne scaturì una fiamma e dalla fiamma balzarono due piccioni, uno d’oro e uno d’argento. Volarono intorno alla testa della ragazza quando tre chicchi d’orzo caddero sul pavimento e il piccione d’argento scese in picchiata e li divorò.

“Se ti fossi rammentato come ho pulito la stalla, mi avresti dato la mia parte.” tubò il piccione d’oro e, mentre parlava, altri tre chicchi caddero e il piccione d’argento li mangiò come prima.

“Se ti fossi rammentato come ho ricoperto la stalla, mi avresti dato la mia parte.” tubà di nuovo il piccione d’oro; e come parlò, caddero altri tre chicchi e per la terza volta furono mangiati dal piccione d’argento.

“Se ti fossi rammentato di come presi il nido della gazza, mi avresti dato la mia parte.” tubò il piccione d’oro.

Allora il figlio del re comprese che erano venuti a rammentargli ciò che aveva dimenticato e gli tornò la memoria perduta, riconobbe la moglie e la baciò. Ma siccome i preparativi erano stati fatti e sembrava un peccato sprecarli, si sposarono una seconda volta e sedettero al banchetto di nozze.

Da Storie delle Highland occidentali

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)