The Winning of Olwen

(MP3-26'23'')

There was once a king and queen who had a little boy, and they called his name Kilwch. The queen, his mother, fell ill soon after his birth, and as she could not take care of him herself she sent him to a woman she knew up in the mountains, so that he might learn to go out in all weathers, and bear heat and cold, and grow tall and strong. Kilwch was quite happy with his nurse, and ran races and climbed hills with the children who were his playfellows, and in the winter, when the snow lay on the ground, sometimes a man with a harp would stop and beg for shelter, and in return would sing them songs of strange things that had happened in the years gone by.

But long before this, changes had taken place in the court of Kilwch's father. Soon after she had sent her baby away the queen became much worse, and at length, seeing that she was going to die, she called her husband to her and said:

'Never again shall I rise from this bed, and by and bye thou wilt take another wife. But lest she should make thee forget thy son, I charge thee that thou take not a wife until thou see a briar with two blossoms upon my grave.' And this he promised her. Then she further bade him to see to her grave that nothing might grow thereon. This likewise he promised her, and soon she died, and for seven years the king sent a man every morning to see that nothing was growing on the queen's grave, but at the end of seven years he forgot.

One day when the king was out hunting he rode past the place where the queen lay buried, and there he saw a briar growing with two blossoms on it.

'It is time that I took a wife,' said he, and after long looking he found one. But he did not tell her about his son; indeed he hardly remembered that he had one till she heard it at last from an old woman whom she had gone to visit. And the new queen was very pleased, and sent messengers to fetch the boy, and in his father's court he stayed, while the years went by till one day the queen told him that a prophecy had foretold that he was to win for his wife Olwen the daughter of Yspaddaden Penkawr.

When he heard this Kilwch felt proud and happy. Surely he must be a man now, he thought, or there would be no talk of a wife for him, and his mind dwelt all day upon his promised bride, and what she would be like when he beheld her.

'What aileth thee, my son?' asked his father at last, when Kilwch had forgotten something he had been bidden to do, and Kilwch blushed red as he answered:

'My stepmother says that none but Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden Penkawr, shall be my wife.'

'That will be easily fulfilled,' replied his father. 'Arthur the king is thy cousin. Go therefore unto him and beg him to cut thy hair, and to grant thee this boon.'

Then the youth pricked forth upon a dapple grey horse of four years old, with a bridle of linked gold, and gold upon his saddle. In his hand he bore two spears of silver with heads of steel; a war-horn of ivory was slung round his shoulder, and by his side hung a golden sword. Before him were two brindled white-breasted greyhounds with collars of rubies round their necks, and the one that was on the left side bounded across to the right side, and the one on the right to the left, and like two sea-swallows sported round him. And his horse, cast up four sods with his four hoofs, like four swallows in the air about his head, now above, now below. About him was a robe of purple, and an apple of gold was at each corner, and every one of the apples was of the value of a hundred cows. And the blades of grass bent not beneath him, so light were his horse's feet as he journeyed toward the gate of Arthur's palace.

'Is there a porter?' cried Kilwch, looking round for some one to open the gate.

'There is; and I am Arthur's porter every first day of January,' answered a man coming out to him. 'The rest of the year there are other porters, and among them Pennpingyon, who goes upon his head to save his feet.'

'Well, open the portal, I say.'

'No, that I may not do, for none can enter save the son of a king or a pedlar who has goods to sell. But elsewhere there will be food for thy dogs and hay for thy horse, and for thee collops cooked and peppered, and sweet wine shall be served in the guest chamber.'

'That will not do for me,' answered Kilwch. 'If thou wilt not open the gate I will send up three shouts that shall be heard from Cornwall unto the north, and yet again to Ireland.'

'Whatsoever clamour thou mayest make,' spake Glewlwyd the porter, 'thou shalt not enter until I first go and speak with Arthur.'

Then Glewlwyd went into the hall, and Arthur said to him:

'Hast thou news from the gate?' and the porter answered:

'Far have I travelled, both in this island and elsewhere, and many kingly men have I seen; but never yet have I beheld one equal in majesty to him who now stands at the door.'

'If walking thou didst enter here, return thou running,' replied Arthur, 'and let every one that opens and shuts the eye show him respect and serve him, for it is not meet to keep such a man in the wind and rain.' So Glewlwyd unbarred the gate and Kilwch rode in upon his charger.

'Greeting unto thee, O ruler of this land,' cried he, 'and greeting no less to the lowest than to the highest.'

'Greeting to thee also,' answered Arthur. 'Sit thou between two of my warriors, and thou shalt have minstrels before thee and all that belongs to one born to be a king, while thou remainest in my palace.'

'I am not come,' replied Kilwch, 'for meat and drink, but to obtain a boon, and if thou grant it me I will pay it back, and will carry thy praise to the four winds of heaven. But if thou wilt not grant it to me, then I will proclaim thy discourtesy wherever thy name is known.'

'What thou askest that shalt thou receive,' said Arthur, 'as far as the wind dries and the rain moistens, and the sun revolves and the sea encircles and the earth extends. Save only my ship and my mantle, my sword and my lance, my shield and my dagger, and Guinevere my wife.'

'I would that thou bless my hair,' spake Kilwch, and Arthur answered:

'That shall be granted thee.'

Forthwith he bade his men fetch him a comb of gold and a scissors with loops of silver, and he combed the hair of Kilwch his guest.

'Tell me who thou art,' he said, 'for my heart warms to thee, and I feel thou art come of my blood.'

'I am Kilwch, son of Kilydd,' replied the youth.

'Then my cousin thou art in truth,' replied Arthur, 'and whatsoever boon thou mayest ask thou shalt receive.'

'The boon I crave is that thou mayest win for me Olwen, the daughter of Yspaddaden Penkawr, and this boon I seek likewise at the hands of thy warriors. From Sol, who can stand all day upon one foot; from Ossol, who, if he were to find himself on the top of the highest mountain in the world, could make it into a level plain in the beat of a bird's wing; from Clust, who, though he were buried under the earth, could yet hear the ant leave her nest fifty miles away: from these and from Kai and from Bedwyr and from all thy mighty men I crave this boon.'

'O Kilwch,' said Arthur, 'never have I heard of the maiden of whom thou speakest, nor of her kindred, but I will send messengers to seek her if thou wilt give me time.'

'From this night to the end of the year right willingly will I grant thee,' replied Kilwch; but when the end of the year came and the messengers returned Kilwch was wroth, and spoke rough words to Arthur.

It was Kai, the boldest of the warriors and the swiftest of foot—he who could pass nine nights without sleep, and nine days beneath the water—that answered him:

'Rash youth that thou art, darest thou speak thus to Arthur? Come with us, and we will not part company till we have won that maiden, or till thou confess that there is none such in the world.'

Then Arthur summoned his five best men and bade them go with Kilwch. There was Bedwyr the one-handed, Kai's comrade and brother in arms, the swiftest man in Britain save Arthur; there was Kynddelig, who knew the paths in a land where he had never been as surely as he did those of his own country; there was Gwrhyr, that could speak all tongues; and Gwalchmai the son of Gwyar, who never returned till he had gained what he sought; and last of all there was Menw, who could weave a spell over them so that none might see them, while they could see every one.

So these seven journeyed together till they reached a vast open plain in which was a fair castle. But though it seemed so close it was not until the evening of the third day that they really drew near to it, and in front of it a flock of sheep was spread, so many in number that there seemed no end to them. A shepherd stood on a mound watching over them, and by his side was a dog, as large as a horse nine winters old.

'Whose is this castle, O herdsman?' asked the knights.

'Stupid are ye truly,' answered the herdsman. 'All the world knows that this is the castle of Yspaddaden Penkawr.'

'And who art thou?'

'I am called Custennin, brother of Yspaddaden, and ill has he treated me. And who are you, and what do you here?'

'We come from Arthur the king, to seek Olwen the daughter of Yspaddaden,' but at this news the shepherd gave a cry:

'O men, be warned and turn back while there is yet time. Others have gone on that quest, but none have escaped to tell the tale,' and he rose to his feet as if to leave them. Then Kilwch held out to him a ring of gold, and he tried to put it on his finger, but it was too small, so he placed it in his glove, and went home and gave it to his wife.

'Whence came this ring?' asked she, 'for such good luck is not wont to befall thee.'

'The man to whom this ring belonged thou shalt see here in the evening,' answered the shepherd; 'he is Kilwch, son of Kilydd, cousin to king Arthur, and he has come to seek Olwen.' And when the wife heard that she knew that Kilwch was her nephew, and her heart yearned after him, half with joy at the thought of seeing him, and half with sorrow for the doom she feared.

Soon they heard steps approaching, and Kai and the rest entered into the house and ate and drank. After that the woman opened a chest, and out of it came a youth with curling yellow hair.

'It is a pity to hide him thus,' said Gwrhyr, 'for well I know that he has done no evil.'

'Three and twenty of my sons has Yspaddaden slain, and I have no more hope of saving this one,' replied she, and Kai was full of sorrow and answered:

'Let him come with me and be my comrade, and he shall never be slain unless I am slain also.' And so it was agreed.

'What is your errand here?' asked the woman.

'We seek Olwen the maiden for this youth,' answered Kai; 'does she ever come hither so that she may be seen?'

'She comes every Saturday to wash her hair, and in the vessel where she washes she leaves all her rings, and never does she so much as send a messenger to fetch them.'

'Will she come if she is bidden?' asked Kai, pondering.

'She will come; but unless you pledge me your faith that you will not harm her I will not fetch her.'

'We pledge it,' said they, and the maiden came.

A fair sight was she in a robe of flame-coloured silk, with a collar of ruddy gold about her neck, bright with emeralds and rubies. More yellow was her head than the flower of the broom, and her skin was whiter than the foam of the wave, and fairer were her hands than the blossom of the wood anemone. Four white trefoils sprang up where she trod, and therefore was she called Olwen.

She entered, and sat down on a bench beside Kilwch, and he spake to her:

'Ah, maiden, since first I heard thy name I have loved thee—wilt thou not come away with me from this evil place?'

'That I cannot do,' answered she, 'for I have given my word to my father not to go without his knowledge, for his life will only last till I am betrothed. Whatever is, must be, but this counsel I will give you. Go, and ask me of my father, and whatsoever he shall require of thee grant it, and thou shalt win me; but if thou deny him anything thou wilt not obtain me, and it will be well for thee if thou escape with thy life.'

'All this I promise,' said he.

So she returned to the castle, and all Arthur's men went after her, and entered the hall.

'Greeting to thee, Yspaddaden Penkawr,' said they. 'We come to ask thy daughter Olwen for Kilwch, son of Kilydd.'

'Come hither to-morrow and I will answer you,' replied Yspaddaden Penkawr, and as they rose to leave the hall he caught up one of the three poisoned darts that lay beside him and flung it in their midst. But Bedwyr saw and caught it, and flung it back so hard that it pierced the knee of Yspaddaden.

'A gentle son-in-law, truly!' he cried, writhing with pain. 'I shall ever walk the worse for this rudeness. Cursed be the smith who forged it, and the anvil on which it was wrought!'

That night the men slept in the house of Custennin the herdsman, and the next day they proceeded to the castle, and entered the hall, and said:

'Yspaddaden Penkawr, give us thy daughter and thou shalt keep her dower. And unless thou wilt do this we will slay thee.'

'Her four great grandmothers and her four great grandfathers yet live,' answered Yspaddaden Penkawr; 'it is needful that I take counsel with them.'

'Be it so; we will go to meat,' but as they turned he took up the second dart that lay by his side and cast it after them. And Menw caught it, and flung it at him, and wounded him in the chest, so that it came out at his back.

'A gentle son-in-law, truly!' cried Yspaddaden; 'the iron pains me like the bite of a horse-leech. Cursed be the hearth whereon it was heated, and the smith who formed it!'

The third day Arthur's men returned to the palace into the presence of Yspaddaden.

'Shoot not at me again,' said he, 'unless you desire death. But lift up my eyebrows, which have fallen over my eyes, that I may see my son-in-law.' Then they arose, and as they did so Yspaddaden Penkawr took the third poisoned dart and cast it at them. And Kilwch caught it, and flung it back, and it passed through his eyeball, and came out on the other side of his head.

'A gentle son-in-law, truly! Cursed be the fire in which it was forged and the man who fashioned it!'

The next day Arthur's men came again to the palace and said:

'Shoot not at us any more unless thou desirest more pain than even now thou hast, but give us thy daughter without more words.'

'Where is he that seeks my daughter? Let him come hither so that I may see him.' And Kilwch sat himself in a chair and spoke face to face with him.

'Is it thou that seekest my daughter?'

'It is I,' answered Kilwch.

'First give me thy word that thou wilt do nothing towards me that is not just, and when thou hast won for me that which I shall ask, then thou shalt wed my daughter.'

'I promise right willingly,' said Kilwch. 'Name what thou wilt.'

'Seest thou yonder hill? Well, in one day it shall be rooted up and ploughed and sown, and the grain shall ripen, and of that wheat I will bake the cakes for my daughter's wedding.'

'It will be easy for me to compass this, although thou mayest deem it will not be easy,' answered Kilwch, thinking of Ossol, under whose feet the highest mountain became straightway a plain, but Yspaddaden paid no heed, and continued:

'Seest thou that field yonder? When my daughter was born nine bushels of flax were sown therein, and not one blade has sprung up. I require thee to sow fresh flax in the ground that my daughter may wear a veil spun from it on the day of her wedding.'

'It will be easy for me to compass this.'

'Though thou compass this there is that which thou wilt not compass. For thou must bring me the basket of Gwyddneu Garanhir which will give meat to the whole world. It is for thy wedding feast. Thou must also fetch me the drinking-horn that is never empty, and the harp that never ceases to play until it is bidden. Also the comb and scissors and razor that lie between the two ears of Trwyth the boar, so that I may arrange my hair for the wedding. And though thou get this yet there is that which thou wilt not get, for Trwyth the boar will not let any man take from him the comb and the scissors, unless Drudwyn the whelp hunt him. But no leash in the world can hold Drudwyn save the leash of Cant Ewin, and no collar will hold the leash except the collar of Canhastyr.'

'It will be easy for me to compass this, though thou mayest think it will not be easy,' Kilwch answered him.

'Though thou get all these things yet there is that which thou wilt not get. Throughout the world there is none that can hunt with this dog save Mabon the son of Modron. He was taken from his mother when three nights old, and it is not known where he now is, nor whether he is living or dead, and though thou find him yet the boar will never be slain save only with the sword of Gwrnach the giant, and if thou obtain it not neither shalt thou obtain my daughter.'

'Horses shall I have, and knights from my lord Arthur. And I shall gain thy daughter, and thou shalt lose thy life.'

The speech of Kilwch the son of Kilydd with Yspaddaden Penkawr was ended.

Then Arthur's men set forth, and Kilwch with them, and journeyed till they reached the largest castle in the world, and a black man came out to meet them.

'Whence comest thou, O man?' asked they, 'and whose is that castle?'

'That is the castle of Gwrnach the giant, as all the world knows,' answered the man, 'but no guest ever returned thence alive, and none may enter the gate except a craftsman, who brings his trade.' But little did Arthur's men heed his warning, and they went straight to the gate.

'Open!' cried Gwrhyr.

'I will not open,' replied the porter.

'And wherefore?' asked Kai.

'The knife is in the meat, and the drink is in the horn, and there is revelry in the hall of Gwrnach the giant, and save for a craftsman who brings his trade the gate will not be opened to-night.'

'Verily, then, I may enter,' said Kai, 'for there is no better burnisher of swords than I.'

'This will I tell Gwrnach the giant, and I will bring thee his answer.'

'Bid the man come before me,' cried Gwrnach, when the porter had told his tale, 'for my sword stands much in need of polishing,' so Kai passed in and saluted Gwrnach the giant.

'Is it true what I hear of thee, that thou canst burnish swords?'

'It is true,' answered Kai. Then was the sword of Gwrnach brought to him.

'Shall it be burnished white or blue?' said Kai, taking a whetstone from under his arm.

'As thou wilt,' answered the giant, and speedily did Kai polish half the sword. The giant marvelled at his skill, and said:

'It is a wonder that such a man as thou shouldst be without a companion.'

'I have a companion, noble sir, but he has no skill in this art.'

'What is his name?' asked the giant.

'Let the porter go forth, and I will tell him how he may know him. The head of his lance will leave its shaft, and draw blood from the wind, and descend upon its shaft again.' So the porter opened the gate and Bedwyr entered.

Now there was much talk amongst those who remained without when the gate closed upon Bedwyr, and Goreu, son of Custennin, prevailed with the porter, and he and his companions got in also and hid themselves.

By this time the whole of the sword was polished, and Kai gave it into the hand of Gwrnach the giant, who felt it and said:

'Thy work is good; I am content.'

Then said Kai:

'It is thy scabbard that hath rusted thy sword; give it to me that I may take out the wooden sides of it and put in new ones.' And he took the scabbard in one hand and the sword in the other, and came and stood behind the giant, as if he would have sheathed the sword in the scabbard. But with it he struck a blow at the head of the giant, and it rolled from his body. After that they despoiled the castle of its gold and jewels, and returned, bearing the sword of the giant, to Arthur's court.

They told Arthur how they had sped, and they all took counsel together, and agreed that they must set out on the quest for Mabon the son of Modron, and Gwrhyr, who knew the languages of beasts and of birds, went with them. So they journeyed until they came to the nest of an ousel, and Gwrhyr spoke to her.

'Tell me if thou knowest aught of Mabon the son of Modron, who was taken when three nights old from between his mother and the wall.'

And the ousel answered:

'When I first came here I was a young bird, and there was a smith's anvil in this place. But from that time no work has been done upon it, save that every evening I have pecked at it, till now there is not so much as the size of a nut remaining thereof. Yet all that time I have never once heard of the man you name. Still, there is a race of beasts older than I, and I will guide you to them.'

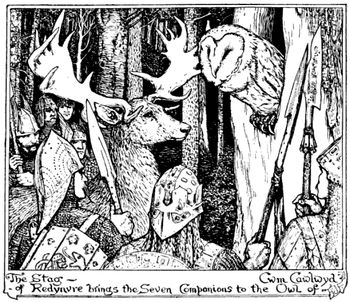

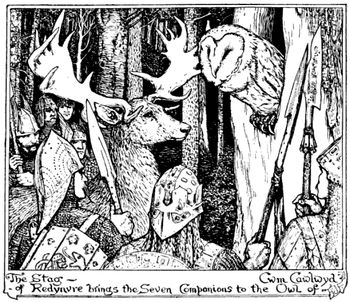

So the ousel flew before them, till she reached the stag of Redynvre; but when they inquired of the stag whether he knew aught of Mabon he shook his head.

'When first I came hither,' said he, 'the plain was bare save for one oak sapling, which grew up to be an oak with a hundred branches. All that is left of that oak is a withered stump, but never once have I heard of the man you name. Nevertheless, as you are Arthur's men, I will guide you to the place where there is an animal older than I;' and the stag ran before them till he reached the owl of Cwm Cawlwyd. But when they inquired of the owl if he knew aught of Mabon he shook his head.

'When first I came hither,' said he, 'the valley was a wooded glen; then a race of men came and rooted it up. After that there grew a second wood, and then a third, which you see. Look at my wings also—are they not withered stumps? Yet until to-day I have never heard of the man you name. Still, I will guide you to the oldest animal in the world, and the one that has travelled most, the eagle of Gwern Abbey.' And he flew before them, as fast as his old wings would carry him, till he reached the eagle of Gwern Abbey, but when they inquired of the eagle whether he knew aught of Mabon he shook his head.

'When I first came hither,' said the eagle, 'there was a rock here, and every evening I pecked at the stars from the top of it. Now, behold, it is not even a span high! But only once have I heard of the man you name, and that was when I went in search of food as far as Llyn Llyw. I swooped down upon a salmon, and struck my claws into him, but he drew me down under water till scarcely could I escape from him. Then I summoned all my kindred to destroy him, but he made peace with me, and I took fifty fish spears from his back. Unless he may know something of the man whom you seek I cannot tell who may. But I will guide you to the place where he is.'

So they followed the eagle, who flew before them, though so high was he in the sky, it was often hard to mark his flight. At length he stopped above a deep pool in a river.

'Salmon of Llyn Llyw,' he called, 'I have come to thee with an embassy from Arthur to inquire if thou knowest aught concerning Mabon the son of Modron?' And the Salmon answered:

'As much as I know I will tell thee. With every tide I go up the river, till I reach the walls of Gloucester, and there have I found such wrong as I never found elsewhere. And that you may see that what I say is true let two of you go thither on my shoulders.' So Kai and Gwrhyr went upon the shoulders of the salmon, and were carried under the walls of the prison, from which proceeded the sound of great weeping.

'Who is it that thus laments in this house of stone?'

'It is I, Mabon the son of Modron.'

'Will silver or gold bring thy freedom, or only battle and fighting?' asked Gwrhyr again.

'By fighting alone shall I be set free,' said Mabon.

Then they sent a messenger to Arthur to tell him that Mabon was found, and he brought all his warriors to the castle of Gloucester and fell fiercely upon it; while Kai and Bedwyr went on the shoulders of the salmon to the gate of the dungeon, and broke it down and carried away Mabon. And he now being free returned home with Arthur.

After this, on a certain day, as Gwrhyr was walking across a mountain he heard a grievous cry, and he hastened towards it. In a little valley he saw the heather burning and the fire spreading fast towards an anthill, and all the ants were hurrying to and fro, not knowing whither to go. Gwrhyr had pity on them, and put out the fire, and in gratitude the ants brought him the nine bushels of flax seed which Yspaddaden Penkawr required of Kilwch. And many of the other marvels were done likewise by Arthur and his knights, and at last it came to the fight with Trwyth the boar, to obtain the comb and the scissors and the razor that lay between his ears. But hard was the boar to catch, and fiercely did he fight when Arthur's men gave him battle, so that many of them were slain.

Up and down the country went Trwyth the boar, and Arthur followed after him, till they came to the Severn sea. There three knights caught his feet unawares and plunged him into the water, while one snatched the razor from him, and another seized the scissors. But before they laid hold of the comb he had shaken them all off, and neither man nor horse nor dog could reach him till he came to Cornwall, whither Arthur had sworn he should not go. Thither Arthur followed after him with his knights, and if it had been hard to win the razor and the scissors, the struggle for the comb was fiercer still. Often it seemed as if the boar would be the victor, but at length Arthur prevailed, and the boar was driven into the sea. And whether he was drowned or where he went no man knows to this day.

In the end all the marvels were done, and Kilwch set forward, and with him Goreu, the son of Custennin, to Yspaddaden Penkawr, bearing in their hands the razor, the scissors and the comb, and Yspaddaden Penkawr was shaved by Kaw.

'Is thy daughter mine now?' asked Kilwch.

'She is thine,' answered Yspaddaden, 'but it is Arthur and none other who has won her for thee. Of my own free will thou shouldst never have had her, for now I must lose my life.' And as he spake Goreu the son of Custennin cut off his head, as it had been ordained, and Arthur's hosts returned each man to his own country.

From the Mabinogion..

La conquista di Olwen

C’ERANO una volta un re e una regina che avevano un bambino di nome Kilwch. La regina sua madre si ammalò poco dopo la sua nascita e siccome non poteva prendersi cura di lui da sola, lo mandò tra le montagne presso una donna che conosceva così che potesse apprendere a resistere a tutte le intemperie, sopportare il caldo e il freddo, crescere alto e forte. Kilwch era molto felice con la sua balia e faceva le corse, si arrampicava sulle colline con i bambini suoi compagni di giochi e in inverno, quando c’era la neve sul terreno, molte volte un uomo con un’arpa si fermava a chiedere ospitalità e in cambio cantava canzoni su strane cose che erano accadute negli anni passati.

Ma molto prima di ciò, erano avvenuti dei cambiamenti alla corte del padre di Kilwch. Poco dopo aver allontanato il bambino, la regina peggiorò sempre di più e alla fine, vedendo di essere prossima alla morte, chiamò a sé il marito e disse:

“Non mi rialzerò più da questo letto e ben presto tu prenderai un’altra moglie. Affinché non ti faccia dimenticare tuo figlio, ti chiedo di non prendere un’altra moglie finché non vedrai sulla mia tomba un tralcio spinoso con due fiori.” Lui promise. Poi gli chiese inoltre di badare alla sua tomba affinché non vi crescesse altro. Egli promise anche questo e lei ben presto morì; per sette anni il re mandò ogni mattina un uomo a vedere che niente crescesse sulla tomba della regina, ma al termine dei sette anni se ne dimenticò.

Un giorno in cui il re era a caccia, passò a cavallo nel luogo in cui era sepolta la regina e vide un tralcio spinoso con due fiori.

“È tempo che prenda moglie.” disse e dopo averla cercata, ne trovò una. Non le disse del figlio; in effetti si rammentava a malapena di averne uno finché lei lo sentì da una vecchia che era andata a trovare. La nuova regina fu molto contenta e mandò messaggeri a prendere il bambino e lui si stabilì alla corte del padre mentre gli anni passavano finché un giorno la regina gli raccontò che una profezia le aveva predetto che lui avrebbe avuto in moglie Olwen, la figlia di Yspaddaden Penkawr.

Quando udì ciò, Kilwch si sentì orgoglioso e felice. Sicuramente ora era un uomo, pensò, o non gli sarebbe stato detto di prender moglie, e la sua mente ogni giorno indugiava sulla promessa sposa e su come gli sarebbe piaciuta quando l’avesse vista.

“Che cosa ti affligge, figlio mio?” chiese alla fine il padre quando Kilwch ebbe dimenticato qualcosa che gli aveva detto di fare, e Kilwch arrossì mentre rispondeva:

“La mia matrigna mi ha detto che nessun’altra sarà la mia sposa se non Olwen, figlia di Yspaddaden Penkawr.”

“Ciò si potrà realizzare facilmente.” rispose il padre. “Re Artù è tuo cugino. Vai dunque al suo servizio e pregalo di tagliarti i capelli e di concederti questo beneficio.”

Allora il giovane principe insistette per avere un cavallo grigio chiazzato di quattro anni, con le briglie d’oro intrecciate e oro anche sulla sella. Portava in mano due lance d’argento con l’impugnatura d’acciaio, appeso alle spalle un corno da guerra in avorio e al suo fianco pendeva una spada d’oro. Lo precedevano due levrieri pezzati dal petto bianco con collari di rubini intorno al collo e quello che era sul lato sinistro si slanciava a destra e quello che era a destra, a sinistra e saltellavano attorno a lui come due rondini di mare. Il suo cavallo, scalciava in aria quattro zolle di terra con gli zoccoli, così come quattro rondini in aria volavano vicino alla sua testa, ora sopra, ora sotto. Indossava un mantello purpureo con una mela d’oro a ogni angolo, e ciascuna di quelle mele valeva quanto cento mucche. E i fili d’erba non si piegavano sotto di lui, tanto era leggero il passo del suo cavallo mentre viaggiava verso le porte del palazzo di Artù.

“C’è un guardiano?” gridò Kilwch, guardandosi attorno in cerca di qualcuno che aprisse il portone.

“Ci sono io; sono il guardiano di Artù dal primo giorno di gennaio.” rispose un uomo che veniva verso dii lui. “Il resto dell’anno ci sono altri guardiani e tra di loro c’è Pennpingyon, che cammina sulla testa per risparmiare i piedi.”

“Ebbene, allora ti dico di aprirmi il portone.”

“Non , non posso farlo perché nessuno può entrare escluso un figlio di re o un venditore ambulante che abbia mercanzia da vendere. Altrove avrai cibo per i tuoi cani e fieno per il tuo cavallo, e per te fettine di carne cucinate e impepate, e vino dolce sarà servito nella stanza degli ospiti.”

“Ciò sarà fatto per me,” rispose Kilwch “ e se non aprirai il portone io emetterò tre urla che saranno udite dalla Cornovaglia al nord e persino in Irlanda.”

“Qualsiasi schiamazzo tu possa produrre,” disse Glewlwyd il guardiano, “non ti farà entrare finché non sarò andato a parlare con Artù.”

Allora Glewlwyd entrò nel salone e Artù gli disse:

“Ci sono novità dal portone?” e il guardiano rispose:

“Ho viaggiato molto lontano, sia in quest’isola che altrove, e ho visto molti uomini dall’aspetto regale, ma non ne avevo mai visto uno pari per maestà a quello che ora è alla porta.”

“Se sei venuto fin qui camminando, ora ritorna correndo,” rispose Artù “e lascia che tutti coloro i quali aprono e chiudono gli occhi gli mostrino rispetto e lo servano perché non si può tenere alla pioggia e al vento un uomo simile.” così Glewlwyd aprì il portone e Kilwch entrò a cavallo.

“Salute a te, signore di questa terra,” esclamò “ e salute tanto a chi sta più in basso quanto a chi sta più in alto.”

“Salute anche a te.” rispose Artù “Siedi tra due dei miei guerrieri e, finché resterai nel mio palazzo, avrai menestrelli davanti a te e tutto ciò che spetta a uno che sia nato per essere re.”

Kilwch rispose: “Non sono venuto per mangiare e bere, ma per ottenere un beneficio e se tu me lo concederai, io saprò ripagarlo e porterò le tue lodi ai quattro venti del cielo. Ma se non me lo concederai , allora proclamerò la tua scortesi ovunque il tuo nome sia conosciuto.”

“Ciò che chiedi sarà ciò che riceverai,” disse Artù, “per quanto lontano il vento porti l’arsura e la pioggia il bagnato, e il sole ruoti e il mare circondi e la terra si estenda. Ad eccezione della mia nave e del mio mantello, della mia spada e della mia lancia, del mio scudo e del mio pugnale e di mia moglie Ginevra.”

“Voglio che mi tagli i capelli.” disse Kilwch e Artù rispose:

“Ti sarà concesso.”

Disse subito ai suoi uomini di portargli un pettine d’oro e un paio di forbici con l’impugnatura d’argento e tagliò i capelli di Kilwch suo ospite.

“Dimmi chi sei,” disse il re “perché il mio cuore si riscalda di fronte a te e mi sento che tu fossi del mio stesso sangue.”

“Sono Kilwch, figlio di Kilydd.” rispose il ragazzo.

“Allora in verità sei mio cugino,” replicò Artù “e qualsiasi beneficio tu possa chiedere, lo riceverai.”

“Il beneficio che imploro è che vostra maestà conquisti per me Olwen, figlia di Yspaddaden Penkawr, e questo beneficio io reclamerò anche dalle mani dei tuoi guerrieri. Da Sol, che può stare tutto il giorno su un piede solo; da Ossol il quale, se si trovasse da solo in cima alla montagna più alta, la renderebbe una pianura nel battito d’ali di un uccello; da Clust il quale, sebbene sepolto sotto terra, potrebbe sentire una formica lasciare il formicaio a cinquanta miglia di distanza; da essi e da Kai e da Bedwyr e da tutti i tuoi possenti uomini io imploro questo beneficio.”

Artù disse: “O Kilwch, non ho mai sentito nulla della fanciulla di chi parli né dei suoi parenti, ma invierò messaggeri a cercarla, se tu me ne darai il tempo.”

“Te lo concederò volentieri da stanotte fino alla fine dell’anno.” rispose Kilwch; ma quando giunse la fine dell’anno e i messaggeri tornarono, Kilwch si adirò e rivolse parole dure ad Artù.

Fu Kai, il più audace dei guerrieri e il più veloce di piede – poteva trascorrere nove notti senza dormire e nove giorni sott’acqua – che gli rispose:

“Giovane sventato che non sei altro, come osi parlare così ad Artù? Vieni con noi e la nostra compagnia non si dividerà finché non avremo conquistato la fanciulla o tu avrai confessato che non ne esista al mondo una simile.”

Allora Artù convocò i suoi cinque migliori uomini e ordinò loro di anadare con Kilwch. Erano Bedwyr il monco, compagno e fratello d’armi di Kai, l’uomo più veloce della Britannia eccetto Artù; c’era Kynddelig, che conosceva come quelli del proprio paese i sentieri di una terra dove non era di certo mai stato; c’era Gwrhyr, che poteva parlare tutte le lingue; e Gwalchmai figlio di Gwyar, che non tornava mai finché non aveva compiuto ciò che aveva intrapreso; e ultimo di tutti era Menw, che avrebbe potuto gettare su di loro un incantesimo così che nessuno potesse vederli mentre essi avrebbero potuto vedere tutti.

Così viaggiarono insieme per sette giorni finché raggiunsero una vasta pianura sulla quale sorgeva un bel castello. Sebbene sembrasse così vicino, fu solo la sera del terzo giorno che giunsero davvero nei pressi e di fronte c’era un gregge di pecore così numeroso che sembrava non aver fine. Un pastore stava su un cumulo a sorvegliarle e al fianco aveva un cane, grande come un cavallo vecchio di nove inverni.

“Pastore, di chi è questo castello?” chiesero i cavalieri.

“Siete davvero stupidi,” rispose il pastore “tutto il mondo sa che è il castello di Yspaddaden Penkawr.”

“E tu chi sei?”

“Mi chiamo Custennin, fratello di Yspaddaden, e lui mi ha trattato male. E voi chi siete e che cosa fate qui?”

“Veniamo da parte di re Artù a chiedere Olwen, figlia di Yspaddaden.” ma a queste parole il pastore lanciò un grido.

“Uomini, state in guardia e tornate indietro finché siete in tempo. Altri hanno intrapreso questa impresa, ma nessuno è scampato per raccontarla.” e si alzò in piedi come se volesse lasciarli. Allora Kilwch gli porse un anello d’oro e lui tentò di infilarselo al dito, ma era troppo piccolo, così lo infilò nel guanto e andò a casa e lo diede alla moglie.

“Da dove viene questo anello?” chiese la donna “Perché una simile fortuna non ti capita spesso.”

“Vedrai qui stasera l’uomo al quale appartiene questo anello.” rispose il pastore “È Kilwch, cugino di Artù, ed è venuto a prendere Olwen.” e quando la moglie sentì ciò, seppe che Kilwch era suo nipote e il suo cuore s’intenerì per lui, diviso a metà tra la gioia al pensiero di vederlo e il dolore per il destino che temeva per lui.

Ben presto sentirono avvicinarsi dei passi e Kai e il resto della compagnia entrarono in casa e mangiarono e bevvero. Dopodiché la donna aprì una cassapanca e ne uscì un giovane dai riccioli biondi.

“È un peccato nasconderlo,” disse Gwrhyr “ sono certo che non abbia fatto alcun male.”

“Ventitré dei miei figli sono stati uccisi da Yspaddaden e non ho più speranza di salvare quest’unico.” disse la donna e Kai, addolorato, rispose:

“Lascialo venire con me come mio compagno e non sarà mai ucciso a meno che non lo sia anche io.” e così fu concordato.

“Per quale impresa siete giunti qui?” chiese la donna.

“Reclamiamo Olwen la fanciulla per questo ragazzo,” rispose Kai “Viene mai qui, così che sia possibile vederla?”

“Viene ogni sabato a lavarsi i capelli e lascia gli anelli nel bacile in cui li lava; non ha mai mandato un messaggero prenderli.”

“Verrà, se sarà chiamata?” chiese Kai, meditando.

“Verrà, ma a meno che non mi darete la vostra parola che non le farete del male, non la manderò a prendere.”

“Te la diamo.” dissero e la fanciulla venne.

Era una visione incantevole con l’abito di seta di un colore fiammeggiante, con una collana d’oro rosso al collo, lucente di smeraldi e di rubini. La sua capigliatura era più dorata del fiore di ginestra e la sua pelle più bianca della schiuma delle onde, e le sue mani erano più graziose dei fiori dell’anemone dei boschi. Quattro trifogli bianchi sbocciavano dove camminasse e perciò era chiamata Olwen.

Entrò e sedette su uno scanno accanto a Kilwch e lui le disse:

“Mia fanciulla, sin dalla prima volta in cui ho udito il tuo nome, ti ho amata… vuoi venire via con me da questo luogo malvagio?”

“Non posso farlo,” rispose lei “perché ho dato la parola a mio padre che non me ne andrò senza il suo permesso visto che lui vivrà solo fino a che sarò promessa sposa. Qualunque cosa sia, deve essere, ma questo è il consiglio che ti do. Vai e chiedimi a mio padre e promettigli qualsiasi cosa ti chiederà così mi otterrai; ma se tu gli rifiuterai qualcosa, non mi avrai e sarà già una cosa buona per te fuggire con salva la vita.”

“Prometto tutto ciò.” disse lui.

Così la fanciulla tornò al castello e tutti gli uomini di Artù la seguirono ed entrarono nel salone.

“Salute a te, Yspaddaden Penkawr,” dissero “siamo venuti a chiederti tua figlia Olwen per Kilwch, figlio di Kilydd.”

“Venite domani e vi darò la risposta.” replicò Yspaddaden Penkawr e mentre loro si alzarono per lasciare il salone, afferrò uno dei tre giavellotti avvelenati che teneva accanto a sé e lo scagliò in mezzo a loro. , ma Bedwyr lo vide, lo afferrò e lo rilanciò indietro con forza tale che si conficcò in un ginocchio di Yspaddaden.

“Davvero un un genero cortese!” gridò, in preda al dolore. “Camminerò sempre male per questa villania. Maledetto il fabbro che l’ha forgiato e l’incudine sul quale è stato battuto!”

Quella notte gli uomini dormirono nella casa di Custennin il pastore e il giorno seguente si diressero al castello, entrarono nel salone e dissero:

“Yspaddaden Penkawr, dacci tua figlia e ti pagheremo la dote. Se non lo farai, ti uccideremo.”

“Le sue quattro bisnonne e i suoi quattro bisnonni vivono ancora,” rispose Yspaddaden Penkawr “è necessario che mi consulti con loro.”

“E sia, noi andremo a mangiare.” ma quando si voltarono, egli afferrò il secondo giavellotto che teneva accanto e e lo scagliò verso di loro. Menw lo afferrò e glielo rilanciò, lo ferì al petto e gli uscì dal dorso.

“Davvero un genero cortese!” gridò Yspaddaden “il ferro mi fa soffrire come il morso di una sanguisuga dei cavalli. Maledetta la fornace in cui è stato fuso e il fabbro che l’ha forgiato!”

Il terzo giorno gli uomini di Artù tornarono a palazzo al cospetto di Yspaddaden.

“Non colpitemi di nuovo,” disse “a meno che non desideriate la morte. Sollevatemi le palpebre che mi sono calate sugli occhi così che possa vedere mio genero.” Allora si alzarono e, mentre lo facevano, Yspaddaden Penkawr prese il terzo giavellotto avvelenato e lo scagliò in mezzo a loro.

Kilwch lo afferrò e lo rilanciò indietro, esso gli trapassò un occhio e uscì dall’altra parte della testa.

“Davvero un genero cortese! Maledetto il fuoco in cui è stato forgiato e l’uomo che l’ha modellato!”

Il giorno seguente gli uomini di Artù andarono di nuovo a palazzo e dissero:

“Non ci colpire un’altra volta se non vuoi soffrire più di quanto tu abbia già fatto ma dacci tua figlia senza senza altre chiacchiere.”

“Dov’è colui che chiede mia figlia? Fatelo venire qui così che possa vederlo.” e Kilwch sedette su una scranna e gli parlò a faccia a faccia.

“Sei tu che chiedi mia figlia?”

“Sì, sono io.” rispose Kilwch.

“Prima dammi la tua parola che non farai nulla contro di me che no sia lecito e quando avrò avuto tutto ciò che ti chiederò, allora potrai sposare mia figlia.”

“Prometto volentieri.” disse Kilwch. “Chiedi quello che vuoi.”

“Vedi quella collina? Ebbene in un giorno dovrà essere ripulita dalle radici, arata, seminata e il grano dovrà essere raccolto; da quella farina saranno cucinate le torte per il matrimonio di mia figlia.”

“Sarà facile per me riuscirci, sebbene tu possa ritenere che non lo sia.” rispose Kilwch, pensando a Ossol, sotto i cui piedi le più alte montagne diventavano subito pianura, ma Yspaddaden fece finta di nulla e continuò:

“Vedi quel campo laggiù? Quando nacque mia figlia vi furono seminati nove stai di semi di lino e non un filo è spuntato. Ti chiedo di seminare semi freschi di lino nel terreno così che mia figlia possa indossare un velo tessuto da essi il giorno delle sue nozze.”

“Sarà facile per me riuscirvi.”

“Sebbene tu ci riesca, vi è qualcosa in cui non riuscirai. Devi portarmi il canestro di Gwyddneu Garanhir che può nutrire il mondo intero. È per il banchetto di nozze. Devi portarmi anche il corno da bevanda che non è mai vuoto e l’arpa che non smette mai di suonare finché non glielo si ordini. E anche il pettine, le forbici e il rasoio che che si trovano tra le orecchie di Trwyth il cinghiale così che io possa sistemarmi i capelli per le nozze. E sebbene tu otterrai tutto ciò, vi è qualcosa che non otterrai perché Trwyth il cinghiale non permette a nessun uomo di prendergli il pettine e le forbici a meno che Drudwyn il cucciolo non gli dia la caccia. Ma nessun guinzaglio al mondo può trattenere Drudwyn, salvo il guinzaglio di Cant Ewin, e nessun collare può reggere il guinzaglio tranne il collare di Canhastyr.”

“Sarà facile per me ottenere ciò, sebbene tu pensi che non lo sia.” gli rispose Kilwch.

“Sebbene tu possa ottenere tutte queste cose, c’è qualcosa che non otterrai. In tutto il mondo non c’è nessuno che possa cacciare con questo cane eccetto Mabon figlio di Modron. È stato rapito a sua madre a tre notti dalla nascita e non si sa sa dove sia ora né se sia vivo o morto, e seppure tu lo trovassi, il cinghiale non potrebbe essere ucciso se non con la spada di Gwrnach il gigante e se non l’otterrai, non otterrai mia figlia.”

“Avrò i cavalli e i cavalieri dal mio sire Artù. Mi guadagnerò tua figlia e tu perderai la vita.”

Il colloquio di Kilwch figlio di Kilydd con Yspaddaden Penkawr era terminato.

Allora gli uomini di Artù se ne andarono e Kilwch con essi; viaggiarono finché raggiunsero il più grande castello del mondo e un uomo nero venne loro incontro.

“Uomo, da dove vieni?” chiesero “E che cos’è quel castello?”

“È il castello di Gwmach il gigante, al mondo lo sanno tutti.” rispose l’uomo “ma nessun ospite è mai tornato vivo da lì e nessuno può oltrepassare il portone eccetto un artigiano che porti con sé il proprio mestiere.” ma gli uomini di Artù dettero poca importanza a questo avvertimento e andarono difilati al portone.

“Aprite!” gridò Gwrhyr.

“Non aprirò.” rispose il guardiano.

“E perché?”

“Il coltello è nella carne e la bevanda nel corno, si fa baldoria nella sala di Gwrnach il gigante e, salvo per un artigiano che porti con sé il proprio mestiere, stanotte il portone non sarà aperto.”

“Allora in verità io posso entrare,” disse Kai “perché non c’è miglior brunitore di spade di me.”

“Lo dirò a Gwrnach il gigante e ti riferirò la sua risposta.”

“Conduci davanti a me quell’uomo” gridò Gwrnach quando il guardiano gli ebbe riferito la faccenda. “perché la mia spada ha proprio bisogno di essere lucidata. Così Kai entrò e salutò Gwrnach il gigante.

“È vero ciò che ho sentito di te, che tu puoi brunire le spade?”

“È vero.” rispose Kai. Allora gli fu portata la spada di Gwrnach.

“Preferisci che sia brunita in bianco o in azzurro?” chiese Kai, prendendo da sotto il braccio una pietra da cote.

“Come vuoi tu.” rispose il gigante e velocemente Kai pulì mezza spada. Il gigante si meravigliò della sua abilità e disse.

“”Mi meraviglia che un uomo come te non abbia un compagno.”

“Ho un compagno, nobile signore, ma non ha capacità in quest’arte.”

“Come si chiama?” chiese il gigante.

“Fai uscire il guardiano e ti dirò come potrà riconoscerlo. La punta della sua lancia si staccherà dall’asta, farà sanguinare il vento e scenderà di nuovo sull’asta.” così il guardiano aprì il portone e Bedwyr entrò.

Ci fu una lunga discussione tra coloro i quali erano rimasti fuori quando il portone si era chiuso dietro Bedwyr e Goreu, figlio di Custennin, ebbe la meglio sul guardiano e anche lui e i suoi compagni entrarono e si nascosero.

Nel frattempo la spada era stata lucidata per intero e Kai l’aveva messa in mano a Gwrnach il gigante, che la tastò e disse:

“Il tuo lavoro è buono, sono contento.”

Allora Kai disse:

“È il fodero che ha fatto arrugginire la tua spada; dammelo così che possa levare le parti di legno e metterne di nuove.” E prese il fodero in una mano e la spada nell’altra poi venne a mettersi davanti al gigante come se volesse inguainare la spada nel fodero, ma con essa sferrò un colpo alla testa del gigante che rotolò via dal corpo. Dopodiché spogliò il castello del suo oro e dei suoi gioielli e tornò alla corte di Artù, brandendo la spada del gigante.

Raccontarono ad Artù come avessero avuto successo e tennero consiglio tutti insieme poi concordarono che sarebbero andati alla ricerca di Mabon figlio di Modron e Gwrhyr, che conosceva i linguaggi degli animali e degli uccelli, andò con loro. Così viaggiarono finché giunsero al nido di un merlo femmina e Gwrhyr parlò con lei.

“Dimmi se sai qualcosa di Mabon, figlio di Modron, il quale fu rapito tre notti dopo la nascita da dove si trovava tra sua madre e il muro.”

Il merlo femmina rispose:

“Quando venni qui la prima volta, ero un giovane uccello e in questo luogo c’era l’incudine di un fabbro. Da allora non vi è stato fatto sopra nessun lavoro, salvo che ogni sera lo beccavo finché ora non è rimasto che della dimensione di una noce. Eppure in tutto questo tempo non ho mai sentito nemmeno una volta dell’uomo che tu nomini. Tuttavia c’è una razza di animali più vecchia di me e ti guiderò da loro.”

Così il merlo femmina volò davanti a loro finché raggiunsero il cervo di Redynvre, ma quando gli chiesero se avesse mai conosciuto Mabon, scosse la testa.

“Quando sono venuto qui la prima volta,” disse “la pianura era spoglia salvo un alberello di quercia che è cresciuto fino a diventare una quercia con cento rami. Tutto ciò che è rimasto della quercia è un ceppo inaridito, ma mai una volta ho sentito dell’uomo che tu nomini. Tuttavia, poiché siete uomini di Artù, vi guiderò in un posto in cui c’è un animale più vecchio di me.” e il cervo corse davanti a loro finché raggiunsero il gufo di Cmw Cawlwyd. Ma quando chiesero al gufo se conoscesse Mabon, scosse la testa.

“La prima volta in cui sono venuto qui” disse la valle era tutta un bosco; poi è giunta la razza umana e lo ha abbattuto. Poi è cresciuto un secondo bosco, poi un terzo, che voi vedete. Guadate le mie ali… non sono moncherini rattrappiti? Eppure fino a oggi non ho mai sentito dell’uomo che nomini. Tuttavia vi guiderò dall’animale più vecchio del mondo, quello che più a ha viaggiato, l’aquila di Gwern Abbey.” e volò davanti a loro, più velocemente che gli consentirono le vecchie ali, finché raggiunse l’aquila di Gwern Abbey, ma quando le chiesero se conoscesse Mabon, scosse la testa.

“Quando venni qui la prima volta,” disse l’aquila “c’era una roccia e ogni sera io becchettavo le stelle dalla sua cima. Adesso guardate, non è alta neanche un palmo! Solo una volta ho sentito dell’uomo che nomini ed è stato quando andai in cerca di cibo fino a Llyn Llyw. Scesi a capofitto su un salmone e lo afferrai con gli artigli, ma mi trascinò sott’acqua tanto che riuscii a malapena a sfuggirgli. Allora radunai tutti i miei parenti per distruggerlo, ma lui fece pace con me e io presi cinquanta fiocine dal suo dorso. A meno che lui sappia qualcosa dell’uomo che cercate, io non posso dirvi chi possa. Però vi guiderò nel posto in cui si trova.”

Così seguirono l’aquila, che volò davanti a loro, sebbene così in alto nel cielo che spesso era molto difficile seguire il suo volo. Alla fine si fermò presso una pozza profonda in un fiume.

“Salmone di Llyn Llyw,” chiamò “sono venuto da te con un’ambasciata da parte di Artù che chiede se tu sappia qualcosa riguardo Mabon figlio di Modron.” e il salmone rispose:

“Ti dirò tutto ciò che so. A ogni marea risalgo il fiume finché raggiungo le mura di Gloucester e lì mi sono trovato così male come mai in nessun altro luogo. Per poter vedere che dico la verità, due di voi mi montino sul dorso.” così Kai e Gwrhyr salirono sul dorso del salmone e furono portati sotto le mura della prigione dalle quali proveniva il suono di un intenso pianto.

“Chi si lamenta in questa casa di pietra?”

“Sono io, Mabon figlio di Modron.”

“L’argento e l’oro potranno farti ottenere la libertà o solo battaglia e combattimento?” chiese di nuovo Gwrhyr.

“Con il combattimento sarò libero.” disse Mabon.

Allora mandarono un messaggero ad Artù per dirgli che Mabon era stato trovato e che inviasse tutti i suoi guerrieri al castello di Gloucester e lo attaccassero ferocemente. Mentre Kai e Bedwyr andarono sul dorso del salmone al cancello della prigione e lo abbatterono, portando via Mabon. E adesso che era libero, tornò a casa con Artù.

Dopodiché, un certo giorno, mentre Gwrhyr stava camminando su per una montagna, sentì un pianto penoso e si affrettò in quella direzione. In una piccola valle vide l’erica che bruciava e il fuoco che che si spandeva velocemente verso un formicaio e tutte le formiche si stavano affrettando qua e là, non sapendo dove andare. Gwrhyr ebbe pietà di loro e spense il fuoco, e in segno di gratitudine le formiche gli portarono i nove stai di semi di lino che Yspaddaden Penkawr aveva chiesto a Kilwch. E molte delle altre meraviglie furono trovate così da Artù e dai suoi cavalieri, e alla fine si trovarono a combattere con Trwyth il cinghiale per ottenere il pettine, le forbici e il rasoio che erano tra le sue orecchie. Ma dura fu la lotta con il cinghiale e combatté fieramente quando gli uomini di Artù gli diedero battaglia, così che molti di loro rimasero uccisi.

Trwyth il cinghiale andò su e giù per il paese e Artù lo seguiva dappresso finché giunsero al mare Severn. Lì tre cavalieri gli afferrarono di sorpresa le zampe e lo immersero nell’acqua mentre uno gli sottraeva il rasoio e un altro afferrava le forbici. Ma prima che potessero prendergli il pettine, se li era scrollati di dosso e nessun uomo o cavallo o cane poté raggiungerlo finché arrivò in Cornovaglia, dove Artù aveva giurato che non sarebbe andato. Laggiù Artù gli andò dietro con i suoi cavalieri e se era stato difficile conquistare il rasoio e le forbici, la lotta per il pettine fu ancora più dura. A volte sembrava che il cinghiale avrebbe vinto, ma alla fine prevalse Artù e il cinghiale fu trascinato in mare. Se sia stato affogato o dove sia andato, fino ad oggi nessun uomo lo sa.

Alla fine tutte le meraviglie furono ottenute e Kilwch andò da Yspaddaden Penkawr, e con lui Goreu, figlio di Custennin, portando in mano il rasoio, le forbici e il pettine e Yspaddaden Penkawr fu acconciato da Kai.

“Adesso tua figlia mi appartiene?” chiese Kilwch.

“È tua,” rispose Yspaddaden, “ma è stato Artù e nessun altro a conquistarla per te. Di mia spontanea volontà non l’avresti mai avuta perché io adesso dovrò perdere la vita.” e mentre parlava, Goreu figlio di Custennin gli tagliò la testa come era stato decretato e gli uomini di Artù tornarono ciascuno al proprio paese.

Dal Mabinogion, gruppo di testi in prosa provenienti da manoscritti gallesi medievali, contenenti sia molti eventi storici dell'Alto Medioevo, ma anche numerose reminiscenze mitologiche e antichissime tradizioni (risalenti all'Età del Ferro), che hanno alcune corrispondenze con quelle dell'Irlanda. Questo racconto proviene dalla tradizione gallese e dalla leggenda e ha molto interessato gli studiosi in quanto contiene antiche tradizioni su re Artù. (da Wikipedia)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)