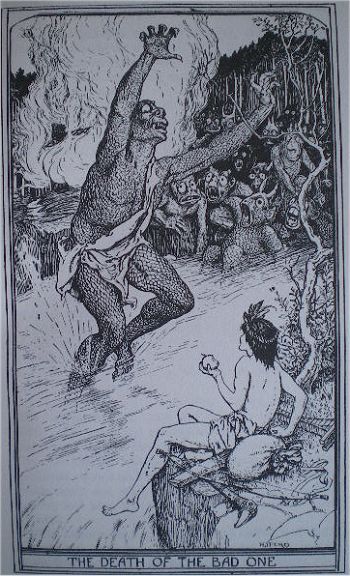

Ball-carrier and the bad One

Far, far in the forest there were two little huts, and in each of them lived a man who was a famous hunter, his wife, and three or four children. Now the children were forbidden to play more than a short distance from the door, as it was known that, away on the other side of the wood near the great river, there dwelt a witch who had a magic ball that she used as a means of stealing children.

Her plan was a very simple one, and had never yet failed. When she wanted a child she just flung her ball in the direction of the child's home, and however far off it might be, the ball was sure to reach it. Then, as soon as the child saw it, the ball would begin rolling slowly back to the witch, just keeping a little ahead of the child, so that he always thought that he could catch it the next minute. But he never did, and, what was more, his parents never saw him again.

Of course you must not suppose that all the fathers and mothers who had lost children made no attempts to find them, but the forest was so large, and the witch was so cunning in knowing exactly where they were going to search, that it was very easy for her to keep out of the way. Besides, there was always the chance that the children might have been eaten by wolves, of which large herds roamed about in winter.

One day the old witch happened to want a little boy, so she threw her ball in the direction of the hunters' huts. A child was standing outside, shooting at a mark with his bow and arrows, but the moment he saw the ball, which was made of glass whose blues and greens and whites, all frosted

over, kept changing one into the other, he flung down his bow, and stooped to pick the ball up. But as he did so it began to roll very gently downhill. The boy could not let it roll away, when it was so close to him, so he gave chase. The ball seemed always within his grasp, yet he could never catch it; it went quicker and quicker, and the boy grew more and more excited. That time he almost touched it—no, he missed it by a hair's breadth! Now, surely, if he gave a spring he could get in front of it! He sprang forward, tripped and fell, and found himself in the witch's house!

'Welcome! welcome! grandson!' said she; 'get up and rest yourself, for you have had a long walk, and I am sure you must be tired!' So the boy sat down, and ate some food which she gave him in a bowl. It was quite different from anything he had tasted before, and he thought it was delicious. When he had eaten up every bit, the witch asked him if he had ever fasted.

'No,' replied the boy, 'at least I have been obliged to sometimes, but never if there was any food to be had.'

'You will have to fast if you want the spirits to make you strong and wise, and the sooner you begin the better.'

'Very well,' said the boy, 'what do I do first?'

'Lie down on those buffalo skins by the door of the hut,' answered she; and the boy lay down, and the squirrels and little bears and the birds came and talked to him.

At the end of ten days the old woman came to him with a bowl of the same food that he had eaten before.

'Get up, my grandson, you have fasted long enough. Have the good spirits visited you, and granted you the strength and wisdom that you desire?'

'Some of them have come, and have given me a portion of both,' answered the boy, 'but many have stayed away from me.'

'Then,' said she, 'you must fast ten days more.'

So the boy lay down again on the buffalo skins, and fasted for ten days, and at the end of that time he turned his face to the wall, and fasted for twenty days longer. At length the witch called to him, and said:

'Come and eat something, my grandson.' At the sound of her voice the boy got up and ate the food she gave him. When he had finished every scrap she spoke as before: 'Tell me, my grandson, have not the good spirits visited you all these many days that you have fasted?'

'Not all, grandmother,' answered he; 'there are still some who keep away from me and say that I have not fasted long enough.'

'Then you must fast again,' replied the old woman, 'and go on fasting till you receive the gifts of all the good spirits. Not one must be missing.'

The boy said nothing, but lay down for the third time on the buffalo skins, and fasted for twenty days more. And at the end of that time the witch thought he was dead, his face was so white and his body so still. But when she had fed him out of the bowl he grew stronger, and soon was able to sit up.

'You have fasted a long time,' said she, 'longer than anyone ever fasted before. Surely the good spirits must be satisfied now?'

'Yes, grandmother,' answered the boy, 'they have all come, and have given me their gifts.'

This pleased the old woman so much that she brought him another basin of food, and while he was eating it she talked to him, and this is what she said: 'Far away, on the other side of the great river, is the home of the Bad One. In his house is much gold, and what is more precious even than the gold, a little bridge, which lengthens out when the Bad One waves his hand, so that there is no river or sea that he cannot cross. Now I want that bridge and some of the gold for myself, and that is the reason that I have stolen so many boys by means of my ball. I have tried to teach them how to gain the gifts of the good spirits, but none of them would fast long enough, and at last I had to send them away to perform simple, easy little tasks. But you have been strong and faithful, and you can do this thing if you listen to what I tell you! When you reach the river tie this ball to your foot, and it will take you across—you cannot manage it in any other way. But do not be afraid; trust to the ball, and you will be quite safe!'

The boy took the ball and put it in a bag. Then he made himself a club and a bow, and some arrows which would fly further than anyone else's arrows, because of the strength the good spirits had given him. They had also bestowed on him the power of changing his shape, and had increased the quickness of his eyes and ears so that nothing escaped him. And in some way or other they made him understand that if he needed more help they would give it to him.

When all these things were ready the boy bade farewell to the witch and set out. He walked through the forest for several days without seeing anyone but his friends the squirrels and the bears and the birds, but though he stopped and spoke to them all, he was careful not to let them know where he was going.

At last, after many days, he came to the river, and beyond it he noticed a small hut standing on a hill which he guessed to be the home of the Bad One. But the stream flowed so quickly that he could not see how he was ever to cross it, and in order to test how swift the current really was, he broke a branch from a tree and threw it in. It seemed hardly to touch the water before it was carried away, and even his magic sight could not follow it. He could not help feeling frightened, but he hated giving up anything that he had once undertaken, and, fastening the ball on his right foot, he ventured on the river. To his surprise he was able to stand up; then a panic seized him, and he scrambled up the bank again. In a minute or two he plucked up courage to go a little further into the river, but again its width frightened him, and a second time he turned back. However, he felt rather ashamed of his cowardice, as it was quite clear that his ball could support him, and on his third trial he got safely to the other side.

Once there he replaced the ball in the bag, and looked carefully round him. The door of the Bad One's hut was open, and he saw that the ceiling was supported by great wooden beams, from which hung the bags of gold and the little bridge. He saw, too, the Bad One sitting in the midst of his treasures eating his dinner, and drinking something out of a horn. It was plain to the boy that he must invent some plan of getting the Bad One out of the way, or else he would never be able to steal the gold or the bridge.

What should he do? Give horrible shrieks as if he were in pain? But the Bad One would not care whether he were murdered or not! Call him by his name? But the Bad One was very cunning, and would suspect some trick. He must try something better than that! Then suddenly an idea came to him, and he gave a little jump of joy. 'Oh, how stupid of me not to think of that before!' said he, and he wished with all his might that the Bad One should become very hungry—so hungry that he could not wait a moment for fresh food to be brought to him. And sure enough at that instant the Bad One called out to his servant, 'You did not bring food that would satisfy a sparrow. Fetch some more at once, for I am perfectly starving.' Then, without giving the woman time to go to the larder, he got up from his chair, and rolled, staggering from hunger, towards the kitchen.

Directly the door had closed on the Bad One the boy ran in, pulled down a bag of gold from the beam, and tucked it under his left arm. Next he unhooked the little bridge and put it under his right. He did not try to escape, as most boys of his age would have done, for the wisdom put into his mind by the good spirits taught him that before he could reach the river and make use of the bridge the Bad One would have tracked him by his footsteps and been upon him. So, making himself very small and thin, he hid himself behind a pile of buffalo skins in the corner, first tearing a slit through one of them, so that he could see what was going on.

He had hardly settled himself when the servant entered the room, and, as she did so, the last bag of gold on the beam fell to the ground—for they had begun to fall directly the boy had taken the first one. She cried to her master that someone had stolen both the bag and the bridge, and the Bad One rushed in, mad with anger, and bade her go and seek for footsteps outside, that they might find out where the thief had gone. In a few minutes she returned, saying that he must be in the house, as she could not see any footsteps leading to the river, and began to move all the furniture in the room, without discovering Ball Carrier.

'But he must be here somewhere,' she said to herself, examining for the second time the pile of buffalo skins; and Ball-Carrier, knowing that he could not possibly escape now, hastily wished that the Bad One should be unable to eat any more food at present.

'Ah, there is a slit in this one,' cried the servant, shaking the skin; 'and here he is.' And she pulled out Ball-Carrier, looking so lean and small that he would hardly have made a mouthful for a sparrow.

'Was it you who took my gold and bridge?' asked the Bad One.

'Yes,' answered Ball-Carrier, 'it was I who took them.'

The Bad One made a sign to the woman, who inquired where he had hidden them. He lifted his left arm where the gold was, and she picked up a knife and scraped his skin so that no gold should be left sticking to it.

'What have you done with the bridge?' said she. And he lifted his right arm, from which she took the bridge, while the Bad One looked on, well pleased. 'Be sure that he does not run away,' chuckled he. 'Boil some water, and get him ready for cooking, while I go and invite my friends the water-demons to the feast.'

The woman seized Ball-Carrier between her finger and thumb, and was going to carry him to the kitchen, when the boy spoke:

'I am very lean and small now,' he said, 'hardly worth the trouble of cooking; but if you were to keep me two days, and gave me plenty of food, I should get big and fat. As it is, your friends the water-demons would think you meant to laugh at them, when they found that I was the feast.'

'Well, perhaps you are right,' answered the Bad One; 'I will keep you for two days.' And he went out to visit the water-demons.

Meanwhile the servant, whose name was Lung Woman, led him into a little shed, and chained him up to a ring in the wall. But food was given him every hour, and at the end of two days he was as fat and big as a Christmas turkey, and could hardly move his head from one side to the other.

'He will do now,' said the Bad One, who came constantly to see how he was getting on. 'I shall go and tell the water-demons that we expect them to dinner to-night. Put the kettle on the fire, but be sure on no account to taste the broth.'

Lung-Woman lost no time in obeying her orders. She built up the fire, which had got very low, filled the kettle with water, and passing a rope which hung from the ceiling through the handle, swung it over the flames. Then she brought in Ball-Carrier, who, seeing all these preparations, wished that as long as he was in the kettle the water might not really boil, though it would hiss and bubble, and also, that the spirits would turn the water into fat.

The kettle soon began to sing and bubble, and Ball Carrier was lifted in. Very soon the fat which was to make the sauce rose to the surface, and Ball-Carrier, who was bobbing about from one side to the other, called out that Lung-Woman had better taste the broth, as he though that some salt should be added to it. The servant knew quite well that her master had forbidden her to do any thing of the kind, but when once the idea was put into her head, she found the smell from the kettle so delicious that she unhooked a long ladle from the wall and plunged it into the kettle.

'You will spill it all, if you stand so far off,' said the boy; 'why don't you come a little nearer?' And as she did so he cried to the spirits to give him back his usual size and strength and to make the water scalding hot. Then he gave the kettle a kick, which upset all the boiling water upon her, and jumping over her body he seized once more the gold and the bridge, picked up his club and bow and arrows, and after setting fire to the Bad One's hut, ran down to the river, which he crossed safely by the help of the bridge.

The hut, which was made of wood, was burned to the ground before the Bad One came back with a large crowd of water-demons. There was not a sign of anyone or anything, so he started for the river, where he saw Ball Carrier sitting quietly on the other side. Then the Bad One knew what had happened, and after telling the water demons that there would be no feast after all, he called to Ball-Carrier, who was eating an apple.

'I know your name now,' he said, 'and as you have ruined me, and I am not rich any more, will you take me as your servant?'

'Yes, I will, though you have tried to kill me,' answered Ball-Carrier, throwing the bridge across the water as he spoke. But when the Bad One was in the midst of the stream, the boy wished it to become small; and the Bad One fell into the water and was drowned, and the world was rid of him.

[U.S. Bureau of Ethnology.]

Porta-la-Palla e il Cattivo

Lontano, lontano nella foresta c'erano due capanne e in ciascuna di esse vivevano un uomo, che era un famoso cacciatore, sua moglie e tre o quattro bambini. Ai bambini era proibito giocare a poco più che breve distanza dalla porta, perché si sapeva che, all'altro lato del bosco, vicino al grande fiume, abitava una strega che aveva una palla magica che era solita usare per rapire i bambini.

Il suo piano era assai semplice e non aveva mai fallito. Quando voleva un bambino, doveva solo lanciare la palla in direzione della casa del fanciullo e comunque fosse lontano, la palla era certa di raggiungerlo. Allora, appena il bambino la vedeva, la palla rotolava lentamente indietro verso la strega, restando appena in vantaggio sul bambino, così che lui pensava sempre che l'avrebbe presa di lì a poco. Ma non accadeva mai e, inoltre, i suoi genitori non lo rivedevano più.

Naturalmente non dovete credere che tutti i padri e le madri che avevano perso i bambini non tentassero di ritrovarli, ma la foresta era così grande e la strega così astuta nel sapere esattamente dove andassero a cercarli, che era proprio facile per lei tenersi alla larga. Inoltre, c'era sempre la possibilità che i bambini fossero stati mangiati dai lupi, i cui grandi branchi vagabondavano nei dintorni in inverno.

Un giorno capitò che la vecchia strega voleva un maschietto, così lanciò la palla verso la capanna del cacciatore. Un bambino stava fuori, tirando a un bersaglio con l'arco e le frecce, ma nel momento in cui vide la palla, che era fatta di vetro i cui colori blu,

verde e bianco, tutti smerigliati, che si fondevano l'uno con l'altro, buttò giù l'arco e si chinò a prendere la palla.. ma come lo faceva, essa cominciava a rotolare dolcemente in discesa. Il bambino non voleva lasciarla rotolare via quando gli era così vicina, così si mise a inseguirla. La palla sembrava sempre a portata di mano, tuttavia non riusciva mai a prenderla; correva sempre più veloce e il bambino era sempre più eccitato. Una volta l'aveva quasi toccata-no, l'aveva perduta per un pelo! Ora, certamente, se desse una spinta, ci arriverebbe! Saltò avanti, inciampò e cadde, e si trovò in casa della strega!

"Benvenuto! benvenuto! nipote!" disse "Alzati e riposa, perché hai fatto tanta strada e sono certa che devi essere stanco!" così il bambino sedette e mangiò un po' del cibo che lei gli mise in una ciotola.. Era piuttosto diverso da qualsiasi cosa avesse assaggiato prima e pensò che fosse delizioso. Quando ebbe mangiato tutto, la strega gli chiese se avesse mai digiunato.

"No," rispose il bambino, "o almeno a volte sono stato obbligato, ma mai se c'era cibo da mangiare."

"Dovrai digiunare se vuoi che gli spiriti ti rendano forte e saggio, e presto diventerai il migliore."

"Benissimo," disse il bambino, "qual è la prima cosa che devo fare?"

"Sdraiati su queste pelli di bufalo alla porta del capanno," rispose lei; il bambino si sdraiò e scoiattoli, orsetti e uccelli vennero a parlargli.

Dopo dieci giorni la vecchia venne da lui con una ciotola dello stesso cibo che aveva già mangiato.

"Alzati, nipote mio, hai digiunato abbastanza. Gli spiriti buoni ti hanno fatto visita e concesso la forza e la saggezza che desideri?"

"Alcuni di loro sono venuti e mi hanno dato un po' di entrambe," rispose il bambino, "ma altri mi sono stati lontani."

"Allora," disse lei, "devi digiunare altri dieci giorni."

Così il bambino giacque sulle pelli di bufalo e digiunò per dieci giorni; alla fine di quel periodo si girò verso il muro e digiunò per altri venti giorni. Alla fine la strega lo chiamò e gli disse:

"Vieni e mangia qualcosa, nipote mio." Al suono della sua voce il bambino si alzò e mangiò il cibo che lei gli dette. Quando ebbe finito anche l'ultima briciola, gli chiese come la volta precedente: "Dimmi, nipote mio, gli spiriti buoni non ti hanno visitato dopo tutti questi giorni di digiuno?"

"Non tutti, nonna," rispose; "qualcuno è ancora rimasto lontano da me e dice che non ho digiunato abbastanza."

"Allora devi digiunare di nuovo," replicò la vecchia, "e restare digiuno finché avrai ricevuto i doni di tutti gli spiriti. Non ne devi perdere neppure uno."

Il bambino non disse nulla, si sdraiò per la terza volta sulle pelli di bufalo e digiunò per altri venti giorni. Alla fine la strega pensò che fosse morto, tanto il suo viso era pallido e il corpo rigido. Ma quando l'ebbe nutrito con il cibo della ciotola, si sentì più forte e presto fu in grado di mettersi a sedere.

"Hai digiunato a lungo," gli disse la strega, "più a lungo di quanto abbia nessuno prima d'ora. Sicuramente gli spiriti buoni adesso devono essere soddisfatti?"

"Sì, nonna," rispose il bambino, "sono venuti tutti e mi hanno portato I loro doni."

Ciò fece tanto piacere alla vecchia che gli portò un'altra ciotola di cibo, e mentre stava mangiando, gli parlò ed ecco che cosa gli disse:" Lontano, sull'altra riva del grande fiume, c'è la casa del Cattivo. Lì c'è tanto oro, ma, ancora più prezioso dell'oro, un ponticello che si allunga quando il Cattivo muove la mano, così che non c'è fiume o mare che egli non possa attraversare. Io voglio quel ponte e un po' di quell'oro, questa è la ragione per la quale ho rapito tanti bambini per mezzo della mia palla. Ho cercato di insegnare loro come ottenere i doni degli spiriti buoni, ma nessuno di loro ha digiunato abbastanza e alla fine ho dovuto mandarli via a eseguire semplici e facili compiti. Ma tu sei forte e leale e puoi farcela, se ascolterai ciò che ti dico! Quando raggiungi il fiume, legati al piede questa palla e sarai al sicuro!"

Il bambino prese la palla e la mise in una borsa. Poi si fece una clava e un arco, e alcune frecce che potevano andare più lontano di ogni altra freccia grazie alla forza che gli spiriti buoni gli avevano infuso. Essi gli avevano anche conferito il potere di cambiare forma e avevano acuito la rapidità dei suoi occhi e delle sue orecchie cosicché più nulla potesse sfuggirgli. E in un modo o nell'altro gli avevano fatto capire che, se avesse avuto bisogno del loro aiuto, glielo avrebbero concesso.

Quando ebbe preparato tutto, il bambino disse addio alla strega e se ne andò. Cammino per la foresta diversi giorni senza incontrare nessuno all'infuori degli amici scoiattoli, orsi e uccelli, ma benché si fermasse e raccontasse loro tutto, badò bene a non far capire loro dove stesse andando.

Alla fine, dopo vari giorni, giunse al fiume e al di là di esso notò un piccolo capanno che sorgeva su una collina e suppose fosse la casa del Cattivo. Ma il fiume scorreva così veloce che non capiva come avrebbe potuto attraversare; per provare quanto fosse rapida la corrente, staccò un rametto da un albero e lo gettò nel fiume. Aveva appena toccato l'acqua che fu trascinato via e non poté seguirlo neppure con il suo sguardo magico. La paura non l'avrebbe di certo aiutato; detestava rinunciare a qualcosa che aveva appena iniziato e, attaccandosi la palla al piede destro, si avventurò nel fiume. Con sua grande sorpresa fu capace di alzarsi; allora fu colto dal panico e si precipitò di nuovo a riva. In un paio di minuti ritrovò il coraggio di andare un po' più oltre nel fiume, ma di nuovo la sua ampiezza lo spaventò e tornò indietro per la seconda volta. Comunque si vergognava abbastanza della propria codardia, era abbastanza chiaro che la palla lo avrebbe sorretto, e al terzo tentativo raggiunse sano e salvo l'altra sponda.

Una volta lì, ripose la palla nella borsa e si guardò bene attorno. La porta del capanno del Cattivo era aperta e vide che il soffitto era sorretto da grosse travi di legno dalle quali pendevano le borse colme d'oro e il ponticello. Vide anche che il Cattivo se ne stava in mezzo ai suoi tesori, cenando e bevendo qualcosa da un corno. Al bambino era chiaro che dovesse inventari qualcosa per liberarsi del Cattivo, o non sarebbe mai riuscito a rubare l'oro o il ponticello.

Che fare? Lanciare orribili grida come se soffrisse? Ma al Cattivo non sarebbe interessato se lo uccidessero o no! Chiamarlo per nome? Ma il Cattivo era molto astuto e avrebbe sospettato un inganno. Doveva trovare qualcosa di meglio! Allora improvvisamente gli venne un'idea e fece un salto di gioia. "Oh, che stupido a non pensarci prima!" disse, e desiderò con tutte le forze che al Cattivo venisse fame, ma una fame tale da non poter aspettare neppure un momento che gli fosse portato del cibo fresco. E infatti in un attimo il Cattivo chiamò la serva, "non portarmi cibo che potrebbe sfamare un passero. Vanne a prendere subito di più perché sto morendo di fame." Allora, senza dare il tempo alla donna di andare alla dispensa, balzò dalla sedia e ciondolò verso la cucina, stravolto dalla fame.

Appena la porta si fu chiusa dietro il Cattivo, il bambino corse dentro, staccò una borsa d'oro dalla trave e se la infilò sotto il braccio sinistro. Poi sganciò il ponticello e se lo mise sotto il destro. Non cercò di scappare, come avrebbe fatto la maggior parte dei bambini della sua età, perché la saggezza infusa nella sua mente dagli spiriti buoni gli aveva insegnato che prima di poter raggiungere il fiume e usare il ponte, il Cattivo avrebbe seguito le tracce fino a lui. Così, facendosi piccolo e sottile, si nascose dietro a un mucchio di pelli di bufalo in un angolo, facendo un piccolo strappo in una di esse attraverso il quale poter vedere che cosa sarebbe accaduto.

Si era appena sistemato quando la serva entrò nella stanza e, quando l'ebbe fatto, l'ultima borsa d'oro sulla trave cadde a terra - perché avevano incominciato a cadere appena il bambino aveva preso la prima. Lei gridò al padrone che qualcuno aveva rubato sia la borsa che il ponte e il Cattivo si precipitò dentro, folle di rabbia; le ordinò di andare e seguire le tracce fuori per scoprire dove si fosse diretto il ladro. In pochi minuti lei tornò, dicendo che doveva essere in casa perché non aveva visto impronte che conducessero al fiume e cominciò a spostare tutti i mobili nella stanza, senza scoprire Porta-la-Palla.

"Deve essere qui da qualche parte," si disse, esaminando per la seconda volta il mucchio di pelli di bufalo; e Porta-la-Palla, sapendo che non sarebbe riuscito a scappare, rapidamente desiderò che il Cattivo non fosse in grado di mangiare nessun cibo la momento.

"Ah, c'è uno strappo in questa pelle," gridò la serva, scuotendola; "ed eccolo qui." Tirò fuori Porta-la-Palla, che sembrava così magro e piccolo che a malapena sarebbe stato un boccone per un passero.

"Hai preso tu il mio oro e il mio ponte?" chiese il Cattivo.

""Sì,"rispose Porta-la-Palla, "sono stato a prenderli."

Il Cattivo fece un cenno alla donna, che cercasse dove li aveva nascosti. Lui sollevò il braccio sinistro dove c'era l'oro, lei prese un coltello e gli raschiò la pelle così che non vi restasse attaccato dell'oro.

"Che ne hai fatto del ponte?" disse lei. E il bambino alzò il braccio destro, dal quale lei prese il ponte mene il Cattivo guardava compiaciuto. " Sta' pur certo che non scapperà," ridacchiò, "Metti a bollire un po' d'acqua e preparalo per essere cucinato mentre vado a invitare al banchetto i miei amici, i demoni dell'acqua."

La donna afferrò Porta-la-Palla tra le dita e il pollice e stava per portarlo in cucina quando il ragazzo parlò:

"Sono così magro e piccolo," disse, "non vale la pena di cucinarmi; ma se mi concedi due giorni e mi riempi di cibo, diventerò grosso e grasso. Così i demoni dell'acqua tuoi amici penseranno che ti voglia prendere gioco di loro, appena scopriranno che il banchetto ero io."

"Forse hai ragione," rispose il Cattivo; "ti concederò due giorni." E andò a trovare i demoni dell'acqua.

Intanto la serva, il cui nome era Colei-che-soffia-sul-Fuoco, lo condusse in una piccola baracca e lo incatenò a un anello nel muro. Gli portava cibo ogni ora e dopo due giorni il bambino fu grasso e grosso come un tacchino a Natale, e difficilmente poteva girare la testa da una parte all'altra.

"È pronto," disse il Cattivo, che andava regolarmente a vedere quanto aumentasse. "Andrò a dire ai demoni dell'acqua che li aspetto stasera a cena. Metti sul fuoco il bollitore, ma assicurati di non assaggiare per nessuna ragione la minestra."

Colei-che-soffia-sul-Fuoco non indugiò a obbedirgli. Attizzò il fuoco, che era assai basso, riempì d'acqua il bollitore e, passando nel manico una corda che pendeva dal soffitto, lo mise sulle fiamme. Poi prese Porta-la-Palla il quale, vedendo la preparazione, desiderò che finché lui fosse stato nel bollitore, l'acqua non bollisse davvero, benché sibilasse e spumeggiasse, e inoltre che gli spiriti mutassero l'acqua in grasso.

Ben presto il bollitore cominciò a gorgogliare e a spumeggiare, e Porta-la-Palla vi fu gettato. Assai presto il grasso della salsa salì alla superficie e Porta-la-palla, che stava andando su e giù da una parte all'altra, gridò che sarebbe stato meglio che Colei-che-soffia-sul-Fuoco assaggiasse la minestra, perché lui pensava che dovesse essere aggiunto un po' di sale. La serva sapeva bene che il padrone le aveva proibito di far nulla del genere, ma una volta entratale in testa quell'idea, le sembrò che il profumo della minestra fosse tanto delizioso che staccò dal muro un lungo mestolo e lo immerse nella minestra.

"Verserai tutto, se starai così lontana," disse il bambino; "perché non ti avvicini un po' di più?" Appena lei lo fece, egli chiese agli spiriti di rendergli le dimensioni e la forza primitive e di rendere l'acqua bollente. Allora diede un calcio al bollitore, che riversò l'acqua bollente sulla donna, e oltrepassando il suo corpo con un salto, afferrò di nuovo l'oro e il ponte, raccolse la clava, l'arco e le frecce e, dopo aver dato fuoco al capanno del Cattivo, corse al fiume, che attraversò senza pericoli grazie al ponte.

Il capanno, che era di legno, andò a fuoco prima che il Cattivo tornasse con una gran seguito di demoni dell'acqua. Non si vedeva niente e nessuno, così egli si avviò verso il fiume, dove vide Porta-la-Palla che sedeva tranquillamente sull'altra riva. Allora il Cattivo comprese ciò che era accaduto e, dopo aver detto ai demoni dell'acqua che non ci sarebbe stato più il banchetto, chiamò Porta-la-Palla, il quale stava mangiando una mela.

"So come ti chiami," disse, "E in che modo mi hai rovinato; ho perso la mia ricchezza, mi assumeresti come tuo servitore?"

"Lo farò certamente, benché tu abbia tentato di uccidermi." rispose Porta-la-Palla, gettando il ponte attraverso l'acqua mentre parlava. Ma mentre il Cattivo si trovava in mezzo al fiume, il fanciullo desiderò che si rimpicciolisse; il Cattivo cadde in acqua, annegò e il mondo fu liberato dalla sua presenza.

(Stati Uniti d'America, Dipartimento di Etnologia)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)