The Enchented Head

(MP3-13'37'')

Once upon a time an old woman lived in a small cottage near the sea with her two daughters. They were very poor, and the girls seldom left the house, as they worked all day long making veils for the ladies to wear over their faces, and every morning, when the veils were finished, the mother took them over the bridge and sold them in the city. Then she bought the food that they needed for the day, and returned home to do her share of veil-making.

One morning the old woman rose even earlier than usual, and set off for the city with her wares. She was just crossing the bridge when, suddenly, she knocked up against a human head, which she had never seen there before. The woman started back in horror; but what was her surprise when the head spoke, exactly as if it had a body joined on to it.

‘Take me with you, good mother!’ it said imploringly; ‘take me with you back to your house.’

At the sound of these words the poor woman nearly went mad with terror. Have that horrible thing always at home? Never! never! And she turned and ran back as fast as she could, not knowing that the head was jumping, dancing, and rolling after her. But when she reached her own door it bounded in before her, and stopped in front of the fire, begging and praying to be allowed to stay.

All that day there was no food in the house, for the veils had not been sold, and they had no money to buy anything with. So they all sat silent at their work, inwardly cursing the head which was the cause of their misfortunes.

When evening came, and there was no sign of supper, the head spoke, for the first time that day:

‘Good mother, does no one ever eat here? During all the hours I have spent in your house not a creature has touched anything.’

‘No,’ answered the old woman, ‘we are not eating anything.’

‘And why not, good mother?’

‘Because we have no money to buy any food.’

‘Is it your custom never to eat?’

‘No, for every morning I go into the city to sell my veils, and with the few shillings I get for them I buy all we want. To-day I did not cross the bridge, so of course I had nothing for food.’

‘Then I am the cause of your having gone hungry all day?’ asked the head.

‘Yes, you are,’ answered the old woman.

‘Well, then, I will give you money and plenty of it, if you will only do as I tell you. In an hour, as the clock strikes twelve, you must be on the bridge at the place where you met me. When you get there call out “Ahmed,” three times, as loud as you can. Then a negro will appear, and you must say to him: “The head, your master, desires you to open the trunk, and to give me the green purse which you will find in it.”’ ‘Very well, my lord,’ said the old woman, ‘I will set off at once for the bridge.’ And wrapping her veil round her she went out.

Midnight was striking as she reached the spot where she had met the head so many hours before.

‘Ahmed! Ahmed! Ahmed!’ cried she, and immediately a huge negro, as tall as a giant, stood on the bridge before her.

‘What do you want?’ asked he.

‘The head, your master, desires you to open the trunk, and to give me the green purse which you will find in it.’

‘I will be back in a moment, good mother,’ said he. And three minutes later he placed a purse full of sequins in the old woman’s hand.

No one can imagine the joy of the whole family at the sight of all this wealth. The tiny, tumble-down cottage was rebuilt, the girls had new dresses, and their mother ceased selling veils. It was such a new thing to them to have money to spend, that they were not as careful as they might have been, and by-and-by there was not a single coin left in the purse. When this happened their hearts sank within them, and their faces fell.

‘Have you spent your fortune?’ asked the head from its corner, when it saw how sad they looked. ‘Well, then, go at midnight, good mother, to the bridge, and call out “Mahomet!” three times, as loud as you can. A negro will appear in answer, and you must tell him to open the trunk, and to give you the red purse which he will find there.’

The old woman did not need twice telling, but set off at once for the bridge.

‘Mahomet! Mahomet! Mahomet!’ cried she, with all her might; and in an instant a negro, still larger than the last, stood before her.

‘What do you want?’ asked he.

‘The head, your master, bids you open the trunk, and to give me the red purse which you will find in it.’

‘Very well, good mother, I will do so,’ answered the negro, and, the moment after he had vanished, he reappeared with the purse in his hand.

This time the money seemed so endless that the old woman built herself a new house, and filled it with the most beautiful things that were to be found in the shops. Her daughters were always wrapped in veils that looked as if they were woven out of sunbeams, and their dresses shone with precious stones. The neighbours wondered where all this sudden wealth had sprung from, but nobody knew about the head.

‘Good mother,’ said the head, one day, ‘this morning you are to go to the city and ask the sultan to give me his daughter for my bride.’

‘Do what?’ asked the old woman in amazement. ‘How can I tell the sultan that a head without a body wishes to become his son-in-law? They will think that I am mad, and I shall be hooted from the palace and stoned by the children.’

‘Do as I bid you,’ replied the head; ‘it is my will.’

The old woman was afraid to say anything more, and, putting on her richest clothes, started for the palace. The sultan granted her an audience at once, and, in a trembling voice, she made her request.

‘Are you mad, old woman?’ said the sultan, staring at her.

‘The wooer is powerful, O Sultan, and nothing is impossible to him.’

‘Is that true?’

‘It is, O Sultan; I swear it,’ answered she.

‘Then let him show his power by doing three things, and I will give him my daughter.’

‘Command, O gracious prince,’ said she.

‘Do you see that hill in front of the palace?’ asked the sultan. ‘I see it,’ answered she.

‘Well, in forty days the man who has sent you must make that hill vanish, and plant a beautiful garden in its place. That is the first thing. Now go, and tell him what I say.’

So the old woman returned and told the head the sultan’s first condition.

‘It is well,’ he replied; and said no more about it.

For thirty-nine days the head remained in its favourite corner. The old woman thought that the task set before was beyond his powers, and that no more would be heard about the sultan’s daughter. But on the thirty-ninth evening after her visit to the palace, the head suddenly spoke.

‘Good mother,’ he said, ‘you must go to-night to the bridge, and when you are there cry “Ali! Ali! Ali!” as loud as you can. A negro will appear before you, and you will tell him that he is to level the hill, and to make, in its place, the most beautiful garden that ever was seen.’

‘I will go at once,’ answered she. It did not take her long to reach the bridge which led to the city, and she took up her position on the spot where she had first seen the head, and called loudly ‘Ali! Ali! Ali.’ In an instant a negro appeared before her, of such a huge size that the old woman was half frightened; but his voice was mild and gentle as he said: ‘What is it that you want?’

‘Your master bids you level the hill that stands in front of the sultan’s palace and in its place to make the most beautiful garden in the world.’

‘Tell my master he shall be obeyed,’ replied Ali; ‘it shall be done this moment.’ And the old woman went home and gave Ali’s message to the head.

Meanwhile the sultan was in his palace waiting till the fortieth day should dawn, and wondering that not one spadeful of earth should have been dug out of the hill. ‘If that old woman has been playing me a trick,’ thought he, ‘I will hang her! And I will put up a gallows to-morrow on the hill itself.’

But when to-morrow came there was no hill, and when the sultan opened his eyes he could not imagine why the room was so much lighter than usual, and what was the reason of the sweet smell of flowers that filled the air.

‘Can there be a fire?’ he said to himself; ‘the sun never came in at this window before. I must get up and see.’ So he rose and looked out, and underneath him flowers from every part of the world were blooming, and creepers of every colour hung in chains from tree to tree.

Then he remembered. ‘Certainly that old woman’s son is a clever magician!’ cried he; ‘I never met anyone as clever as that. What shall I give him to do next? Let me think. Ah! I know.’ And he sent for the old woman, who by the orders of the head, was waiting below.

‘Your son has carried out my wishes very nicely,’ he said. ‘The garden is larger and better than that of any other king. But when I walk across it I shall need some place to rest on the other side. In forty days he must build me a palace, in which every room shall be filled with different furniture from a different country, and each more magnificent than any room that ever was seen.’ And having said this he turned round and went away.

‘Oh! he will never be able to do that,’ thought she; ‘it is much more difficult than the hill.’ And she walked home slowly, with her head bent.

‘Well, what am I to do next?’ asked the head cheerfully. And the old woman told her story.

‘Dear me! is that all? why it is child’s play,’ answered the head; and troubled no more about the palace for thirty-nine days. Then he told the old woman to go to the bridge and call for Hassan.

‘What do you want, old woman?’ asked Hassan, when he appeared, for he was not as polite as the others had been.

‘Your master commands you to build the most magnificent palace that ever was seen,’ replied she; ‘and you are to place it on the borders of the new garden.’

‘He shall be obeyed,’ answered Hassan. And when the sultan woke he saw, in the distance, a palace built of soft blue marble, resting on slender pillars of pure gold.

‘That old woman’s son is certainly all-powerful,’ cried he; ‘what shall I bid him do now?’ And after thinking some time he sent for the old woman, who was expecting the summons.

‘The garden is wonderful, and the palace the finest in the world,’ said he, ‘so fine, that my servants would cut but a sorry figure in it. Let your son fill it with forty slaves whose beauty shall be unequalled, all exactly like each other, and of the same height.’

This time the king thought he had invented something totally impossible, and was quite pleased with himself for his cleverness.

Thirty-nine days passed, and at midnight on the night of the last the old woman was standing on the bridge.

‘Bekir! Bekir! Bekir!’ cried she. And a negro appeared, and inquired what she wanted.

‘The head, your master, bids you find forty slaves of unequalled beauty, and of the same height, and place them in the sultan’s palace on the other side of the garden.’

And when, on the morning of the fortieth day, the sultan went to the blue palace, and was received by the forty slaves, he nearly lost his wits from surprise.

‘I will assuredly give my daughter to the old woman’s son,’ thought he. ‘If I were to search all the world through I could never find a more powerful son-in-law.’

And when the old woman entered his presence he informed her that he was ready to fulfil his promise, and she was to bid her son appear at the palace without delay.

This command did not at all please the old woman, though, of course, she made no objections to the sultan.

‘All has gone well so far,’ she grumbled, when she told her story to the head,’ but what do you suppose the sultan will say, when he sees his daughter’s husband?’

‘Never mind what he says! Put me on a silver dish and carry me to the palace.’

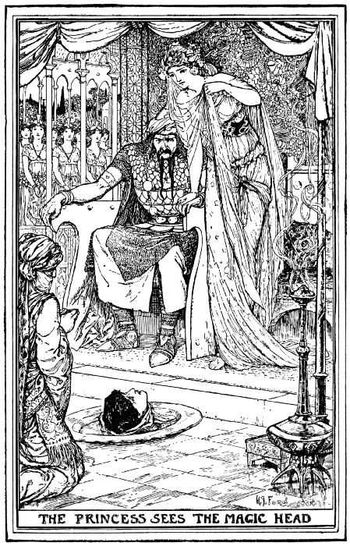

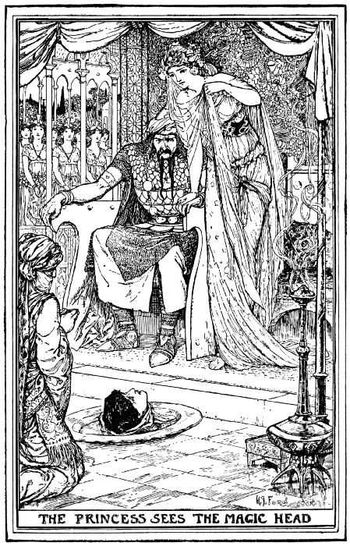

So it was done, though the old woman’s heart beat as she laid down the dish with the head upon it.

At the sight before him the king flew into a violent rage.

‘I will never marry my daughter to such a monster,’ he cried. But the princess placed her head gently on his arm.

‘You have given your word, my father, and you cannot break it,’ said she.

‘But, my child, it is impossible for you to marry such a being,’ exclaimed the sultan.

‘Yes, I will marry him. He had a beautiful head, and I love him already.’

So the marriage was celebrated, and great feasts were held in the palace, though the people wept tears to think of the sad fate of their beloved princess. But when the merry-making was done, and the young couple were alone, the head suddenly disappeared, or, rather, a body was added to it, and one of the handsomest young men that ever was seen stood before the princess.

‘A wicked fairy enchanted me at my birth,’ he said, ‘and for the rest of the world I must always be a head only. But for you, and you only, I am a man like other men.’ ‘And that is all I care about,’ said the princess.

Traditions Populaires de toutes le nations (Asie Mineure)

La testa fatata

C’era una volta una vecchia che viveva in una casetta vicino al mare con le sue due figlie. Erano assai povere e raramente le ragazze lasciavano la casa, perché lavoravano tutto il giorno a cucire veli che le dame indossavano sul volto e ogni mattina, quando i veli erano completati, la madre li portava al di là del ponte e li vendeva in città. Poi acquistava il cibo di cui aveva bisogno per la giornata e tornava a casa al suo lavoro di cucitrice di veli.

Una mattina la vecchia si alzò più presto del solito e andò in città con la mercanzia. Stava giusto attraversando il ponte quando, improvvisamente, incappò in una testa umana, che non aveva mai visto lì prima. La donna indietreggiò inorridita, ma quale fu la sua sorpresa quando la testa parlò, proprio come se avesse un corpo a cui fosse unita.

”Portami con te, buona madre!” la implorò, “Portami con te a casa tua.”

A queste parole la povera donna quasi impazzì di terrore. Avere per sempre a casa quella cosa orribile? Mai! Mai! E si voltò e corse più in fretta che poté, senza sapere che la testa stava saltando, danzando e rotolando dopo di lei. Quando ebbe raggiunto la porta, le balzò davanti e si fermò di fronte al fuoco, pregando e implorando che le fosse permesso di restare.

Per tutto il giorno in casa non vi fu cibo perché i veli non erano stati venduti e non avevano con cui comprare qualcosa. Così sedevano tutte silenziose al lavoro, maledicendo dentro di loro la testa che era stata la causa delle loro disgrazie.

Quando fu sera e non c’era traccia della cena, la testa parlò per la prima volta in quel giorno:

”Buona madre, qui nessuno mangia mai? Durante tutte le ore che ho trascorso in questa casa nessuno ha toccato nulla.”

La vecchia rispose: “No, non abbiamo nulla da mangiare.”

”E perché no, buona madre?”

”Perché non abbiamo denaro per comperare nessun cibo.”

”È vostra consuetudine non mangiare mai?”

”No, perché ogni mattina vado in città a vendere i miei veli e con i pochi denari che ne ricavo, compro tutto ciò che vogliamo. Oggi non ho attraversato il ponte, così naturalmente non ho nulla da mangiare.”

”Allora sono io la causa della vostra fame oggi?” chiese la testa.

”Sì, sei tu.” rispose la vecchia.

”Ebbene, allora vi darò denaro in abbondanza, se solo farete ciò che vi dirò. Entro un’ora, quando l’orologio batterà le dodici, dovrai essere sul ponte nel posto in cui mi hai incontrata. Quando sarai là, grida tre volte ‘Ahmed’, più forte che puoi. Allora apparirà un negro e tu dovrai dirgli: “La testa, tua padrona, desidera che tu apra il baule e mi dia il borsellino verde che vi troverai.”

”Benissimo, signore,” disse la vecchia, “andrò subito al ponte.” E uscì, avvolgendosi nel velo.

Stava suonando la mezzanotte quando raggiunse il luogo in cui aveva incontrato la testa molte ore prima.

”Ahmed! Ahmed! Ahmed!” gridò e immediatamente un imponente negro, alto come un gigante, comparve davanti a lei sul ponte.

”Che cosa vuoi?” le chiese.

”La testa, tua padrona, desidera che tu apra il baule e mi dia il borsellino verde che vi troverai.”

”Tornerò in un attimo, buona madre.” disse. E tre minuti dopo mise in mano alla vecchia un borsellino pieno di zecchini.

Non si può immaginare la gioia dell’intera famiglia alla vista di tutta quella ricchezza. La piccola casa diroccata fu ricostruita, le ragazze ebbero vestiti nuovi e la loro madre smise di vendere veli. Era una cosa tanto nuova per loro possedere denaro da spendere che non furono parsimoniose come avrebbero dovuto essere e di lì a poco non rimase una sola moneta nel borsellino. Quando ciò accadde, i loro cuori sprofondarono e i loro volti s’incupirono.

”Avete speso la vostra fortuna?” chiese la testa dal suo angolo, quando vide come apparivano tristi. “Ebbene, allora, buona madre, a mezzanotte vai sul ponte e chiama tre volte ‘Mahomet!’ più forte che puoi. In risposta comparirà un negro e tu dovrai dirgli di aprire il baule e di darti il borsellino rosso che vi troverà.”

La vecchia non se lo fece dire due volte e andò subito sul ponte.

“Mahomet! Mahomet! Mahomet!” gridò con tutte le forze; in un istante un negro, più grande del precedente, fu davanti a lei.

”Che cosa vuoi?” chiese.

”La testa, tua padrona, dice di aprire il baule e di darmi il borsellino rosso che vi troverai.”

”Benissimo, buona madre, farò così.” rispose il negro e un attimo dopo essere sparito, riapparve con il borsellino in mano.

Stavolta il borsellino sembrava così inesauribile che la vecchia si costruì una nuova casa e la riempì delle cose più belle che si potevano trovare nelle botteghe. Le sue figlie erano sempre avvolte in veli che sembravano intessuti di raggi di sole e i loro abiti scintillavano di pietre preziose. I vicini si domandavano da dove fosse venuta tutta questa improvvisa ricchezza, ma nessuno sapeva della testa.

”Buona madre,” disse un giorno la testa, “stamatttina devi andare in città e chiedere al sultano di darmi sua figlia in moglie.”

”Che cosa?” chiese la vecchia stupita, “Come posso dire al sultano che una testa senza corpo desidera diventare suo genero? Penseranno che io sia pazza e i bambini fuori del palazzo mi grideranno dietro e tireranno pietre.”

”Fai come ti ho detto,” rispose la testa, “è la mia volontà.”

La vecchia ebbe paura di dire altro e, indossando gli abiti più sontuosi, si recò a palazzo. Il sultano le diede subito udienza e, con voce tremante, fece la sua richiesta.

”Vecchia, sei pazza?”, disse il sultano, fissandola.

”Il pretendente è potente, o Sultano, e niente gli è impossibile.”

” È la verità?”

“Sì, o sultano, lo giuro.” rispose la vecchia.

”Allora che mi mostri il suo potere facendo tre cose e io gli darò mia figlia.”

”Comanda, o grazioso principe.” disse lei.

”Vedi quella collina di fronte al palazzo?” chiese il sultano.

“La vedo.” rispose la vecchia.

”Ebbene, in quaranta giorni l’uomo che ti ha mandata deve far sparire quella collina e piantare un meraviglioso giardino al suo posto. Questa è la prima cosa. Ora vai e riferiscigli che cosa ti ho detto.”

Così la vecchia tornò e espose alla testa la prima condizione del sultano.

Va bene.” replicò, e non disse altro al riguardo.

Per trentanove giorni la testa rimase nel suo angolo preferito. La vecchia pensò che l’impresa fosse al di sopra delle sue forze e che non avrebbe sentito altro sulla figlia del sultano, ma la trentanovesima sera dalla sua visita al palazzo, la testa improvvisamente parlò.

”Buona madre,” disse, “stanotte devi andare sul ponte e, quando sarai là, grida ‘Alì! Alì! Alì’ più forte che puoi. Apparirà davanti a te un negro e gli dirai che deve appianare la collina e realizzare, al suo posto, il più bel giardino che si sia mai visto.”

“Andrò subito.” rispose la vecchia.

Non le occorse molto per raggiungere il ponte che conduceva in città e prese posto nel luogo in cui aveva visto per la prima volta la testa, poi chiamò forte: “Alì! Alì! Alì!” in un attimo comparve davanti a lei un negro, così imponente che la vecchia ne fu quasi impaurita; ma la sua voce era dolce e gentile quando le disse: “Che cosa vuoi?”

“Il tuo padrone ordina di appianare la collina che sorge di fronte al palazzo del sultano e di realizzare al suo posto il più bel giardino del mondo.”

“Di’ al mio padrone che sarà obbedito.” rispose Alì. “Sarà fatto all’istante.” E la vecchia tornò a casa e riferì alla testa il messaggio di Alì.

Nel frattempo il sultano era nel suo palazzo ad aspettare che scadesse il quarantesimo giorno, pensando che nessuna vanga del mondo avrebbe spalato via la collina.

“Se la vecchia mi ha giocato un brutto tiro,” pensava, “la farò impiccare! E farò innalzare una forca domani sulla collina stessa.”

Ma il giorno seguente non c’era nessuna collina e, quando il sultano aprì gli occhi, non avrebbe potuto immaginare perché la stanza fosse tanto più luminosa del solito e quale fosse la causa del dolce profumo di fiori che impregnava l’aria.

“Che ci sia un fuoco?” si disse, “Prima il sole non è mai entrato da questa finestra. Devo andare a vedere.” Così si alzò e guardò fuori, e sotto di lui stavano sbocciando fiori di ogni parte del mondo, e rampicanti di ogni colore pendevano da un albero all’altro come catene.

Allora si rammentò. “Certamente il figlio della vecchia è un intelligente mago!” esclamò; “Non ho mai incontrato nessuno così ingegnoso. Che gli darò da fare la prossima volta? Ah! Lo so.” E mandò a chiamare la vecchia la quale, per ordine della testa, stava aspettando di sotto.

“Tuo figlio ha realizzato i miei desideri assai bene” disse. “Il giardino è più grande e migliore di quello di qualsiasi altro re. Ma quando ci passo in mezzo, mi servirà dall’altro lato un posto in cui riposare. In quaranta giorni deve costruirmi un palazzo nel quale ogni stanza sia colmi di mobili diversi di paesi diversi e ognuna più sfarzosa di qualsiasi altra stanza si sia mai vista.” Detto ciò, si voltò e andò via.

“Oh! Non sarà mai in grado di farlo,” pensò la vecchia; “è molto più difficile della collina.” E si mosse lentamente verso casa, con la testa china.

“Ebbene, che cosa devo fare poi?” chiese allegramente la testa. E la vecchia gli narrò la faccenda.

“Povera me! È tutto? Perché si tratta di un gioco da ragazzi.” Rispose la testa; e non lavorò al palazzo per trentanove giorni. Poi disse alla vecchia di andare sul ponte e di chiamare Hassan.

“Che cosa vuoi, vecchia?” chiese Hassan quando apparve, perché non era cortese come lo erano stati gli altri. “Il tuo padrone ti ordina di costruire il palazzo più splendido che si sia mai visto,” rispose lei, “e devi collocarlo ai confini del nuovo giardino.”

“Sarà obbedito.” rispose Hassan. E quando il sultano si svegliò, vide in lontananza un palazzo costruito di delicato marmo azzurro, che posava su snelle colonne d’oro puro.

“Il figlio di quella vecchia è certamente potentissimo,” esclamò; “che cosa gli ordinerò di fare adesso? E dopo avervi pensato un po’, mandò a chiamare la vecchia, che stava aspettando la chiamata.

“Il giardino è meraviglioso e il palazzo è il più bello del mondo,” disse il sultano, “così bello che i miei servi vi farebbero una misera figura. Che tuo figlio vi collochi quaranta schiavi di differente bellezza, tutti esattamente l’uno come l’altro e del medesimo peso.”

Stavolta il sultano pensava di aver escogitato qualcosa di totalmente impossibile e si congratulò con se stesso per l’astuzia.

Trascorsero trentanove giorni e a mezzanotte dell’ultima notte la vecchia era sul ponte.

“Berik! Berik! Berik!” gridava, e apparve un negro a chiederle che cosa volesse. “La testa, tuo padrone, ordina che porti quaranta schiavi di differente bellezza e del medesimo peso e che li collochi nel palazzo del sultano all’altro lato del giardino.”

Quando il mattino del quarantesimo giorno il sultano andò nel palazzo azzurro e fu ricevuto dai quaranta schiavi, quasi perse il senno per la sorpresa.

“Sicuramente concederò mia figlia al figlio della vecchia.” pensò. “Se cercassi in tutto il mondo, non troverei mai un genero così potente.”

E quando la vecchia fu introdotta alla sua presenza, la informò di essere pronto a mantenere la promessa e che le veniva ordinato che il figlio si presentasse a palazzo senza indugio.

Questo ordine non piacque del tutto alla vecchia, sebbene, naturalmente, non facesse obiezioni al sultano.

“Fino ad oggi tutto è andato bene,” brontolò, quando narrò la faccenda alla testa, “ma che cosa supponi dirà il sultano quando vedrà il marito di sua figlia?”

“Non badare a ciò che dirà! Mettimi su un piatto d’argento e portami a palazzo.”

Così fu fatto, sebbene il cuore della vecchia battesse forte mentre posava il piatto con sopra la testa.

Di fronte a quella vista la collera del sultano esplose violenta.

“Non darò mai mia figlia in sposa a un simile mostro.” gridò, ma la principessa prese gentilmente la testa tra le braccia.

“Hai dato la tua parola, padre mio, e non puoi infrangerla.” Disse la principessa.

“Ma, bambina mia, è impossibile che tu sposi una cosa simile.” esclamò il sultano.

”Lo sposerò. Ha una testa meravigliosa e lo amo già.”

Così fu celebrato il matrimonio e a palazzo si tenne una gran festa, sebbene il popolo piangesse al pensiero del triste destino dell’amata principessa. Ma quando la festa fu terminata e la giovane coppia rimase sola, la testa scomparve improvvisamente, o meglio, le fu aggiunto un corpo e davanti alla principessa comparve uno dei giovani più affascinanti che si fosse mai visto. “Una fata malvagia mi ha stregato alla nascita,” disse il giovane, “e per il resto del mondo io devo essere solo una testa. Per te, e solo per te, io sono un uomo come gli altri.”

“E questo è tutto ciò di cui mi importa.” disse la principessa.

Tradizioni popolari di tutte le nazioni (Asia Minore)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)