Over all the vast under-world the mountain Gnome Rubezahl was lord; and busy enough the care of his dominions kept him. There were the endless treasure chambers to be gone through, and the hosts of gnomes to be kept to their tasks. Some built strong barriers to hold back the fiery vapours to change dull stones to precious metal, or were hard at work filling every cranny of the rocks with diamonds and rubies; for Rubezahl loved all pretty things. Sometimes the fancy would take him to leave those gloomy regions, and come out upon the green earth for a while, and bask in the sunshine and hear the birds sing. And as gnomes live many hundreds of years he saw strange things. For, the first time he came up, the great hills were covered with thick forests, in which wild animals roamed, and Rubezahl watched the fierce fights between bear and bison, or chased the grey wolves, or amused himself by rolling great rocks down into the desolate valleys, to hear the thunder of their fall echoing among the hills. But the next time he ventured above ground, what was his surprise to find everything changed! The dark woods were hewn down, and in their place appeared blossoming orchards surrounding cosy-looking thatched cottages; for every chimney the blue smoke curled peacefully into the air, sheep and oxen fed in the flowery meadows, while from the shade of the hedges came the music of the shepherd’s pipe. The strangeness and pleasantness of the sight so delighted the gnome that he never thought of resenting the intrusion of these unexpected guests, who, without saying ‘by your leave’ or ‘with your leave,’ had made themselves so very much at home upon his hills; nor did he wish to interfere with their doings, but left them in quiet possession of their homes, as a good householder leaves in peace the swallows who have built their nests under his eaves. He was indeed greatly minded to make friends with this being called ‘man,’ so, taking the form of an old field labourer, he entered the service of a farmer. Under his care all the crops flourished exceedingly, but the master proved to be wasteful and ungrateful, and Rubezahl soon left him, and went to be shepherd to his next neighbour. He tended the flock so diligently, and knew so well where to lead the sheep to the sweetest pastures, and where among the hills to look for any who strayed away, that they too prospered under his care, and not one was lost or torn by wolves; but this new master was a hard man, and begrudged him his well-earned wages. So he ran away and went to serve the judge. Here he upheld the law with might and main, and was a terror to thieves and evildoers; but the judge was a bad man, who took bribes, and despised the law. Rubezahl would not be the tool of an unjust man, and so he told his master, who thereupon ordered him to be thrown in prison. Of course that did not trouble the gnome at all, he simply got out through the keyhole, and went away down to his underground palace, very much disappointed by his first experience of mankind. But, as time went on, he forgot the disagreeable things that had happened to him, and thought he would take another look at the upper world.

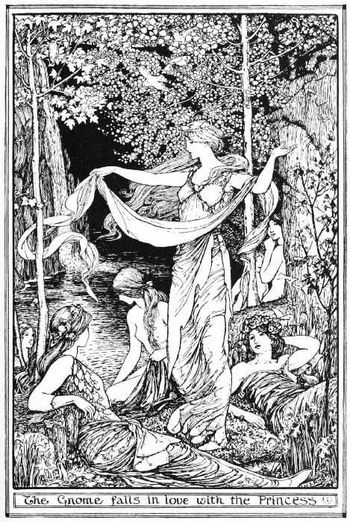

So he stole into the valley, keeping himself carefully hidden in copse or hedgerow, and very soon met with an adventure; for, peeping through a screen of leaves, he saw before him a green lawn where stood a charming maiden, fresh as the spring, and beautiful to look upon. Around her upon the grass lay her young companions, as if they had thrown themselves down to rest after some merry game. Beyond them flowed a little brook, into which a waterfall leapt from a high rock, filling the air with its pleasant sound, and making a coolness even in the sultry noontide.

The sight of the maiden so pleased the gnome that, for the first time, he wished himself a mortal; and, longing for a better view of the gay company, he changed himself into a raven and perched upon an oaktree which overhung the brook. But he soon found that this was not at all a good plan. He could only see with a raven’s eyes, and feel as a raven feels; and a nest of field-mice at the foot of the tree interested him far more than the sport of the maidens. When he understood this he flew down again in a great hurry into the thicket, and took the form of a handsome young man—that was the best way—and he fell in love with the girl then and there. The fair maiden was the daughter of the king of the country, and she often wandered in the forest with her play fellows gathering the wild flowers and fruits, till the midday heat drove the merry band to the shady lawn by the brook to rest, or to bathe in the cool waters. On this particular morning the fancy took them to wander off again into the wood. This was Master Rubezahl’s opportunity. Stepping out of his hiding-place he stood in the midst of the little lawn, weaving his magic spells, till slowly all about him changed, and when the maidens returned at noon to their favourite resting-place they stood lost in amazement, and almost fancied that they must be dreaming. The red rocks had become white marble and alabaster; the stream that murmured and struggled before in its rocky bed, flowed in silence now in its smooth channel, from which a clear fountain leapt, to fall again in showers of diamond drops, now on this side now on that, as the wandering breeze scattered it.

Daisies and forget-me-nots fringed its brink, while tall hedges of roses and jasmine ringed it round, making the sweetest and daintiest bower imaginable. To the right and left of the waterfall opened out a wonderful grotto, its walls and arches glittering with many-coloured rock-crystals, while in every niche were spread out strange fruits and sweetmeats, the very sight of which made the princess long to taste them. She hesitated a while, however, scarcely able to believe her eyes, and not knowing if she should enter the enchanted spot or fly from it. But at length curiosity prevailed, and she and her companions explored to their heart’s content, and tasted and examined everything, running hither and thither in high glee, and calling merrily to each other.

At last, when they were quite weary, the princess cried out suddenly that nothing would content her but to bathe in the marble pool, which certainly did look very inviting; and they all went gaily to this new amusement. The princess was ready first, but scarcely had she slipped over the rim of the pool when down—down—down she sank, and vanished in its depths before her frightened playmates could seize her by so much as a lock of her floating golden hair!

Loudly did they weep and wail, running about the brink of the pool, which looked so shallow and so clear, but which had swallowed up their princess before their eyes. They even sprang into the water and tried to dive after her, but in vain; they only floated like corks in the enchanted pool, and could not keep under water for a second.

They saw at last that there was nothing for it but to carry to the king the sad tidings of his beloved daughter’s disappearance. And what great weeping and lamentation there was in the palace when the dreadful news was told! The king tore his robes, dashed his golden crown from his head, and hid his face in his purple mantle for grief and anguish at the loss of the princess. After the first outburst of wailing, however, he took heart and hurried off to see for himself the scene of this strange adventure, thinking, as people will in sorrow, that there might be some mistake after all. But when he reached the spot, behold, all was changed again! The glittering grotto described to him by the maidens had completely vanished, and so had the marble bath, the bower of jasmine; instead, all was a tangle of flowers, as it had been of old. The king was so much perplexed that he threatened the princess’s playfellows with all sorts of punishments if they would not confess something about her disappearance; but as they only repeated the same story he presently put down the whole affair to the work of some sprite or goblin, and tried to console himself for his loss by ordering a grand hunt; for kings cannot bear to be troubled about anything long.

Meanwhile the princess was not at all unhappy in the palace of her elfish lover.

When the water-nymphs, who were hiding in readiness, had caught her and dragged her out of the sight of her terrified maidens, she herself had not had time to be frightened. They swam with her quickly by strange underground ways to a palace so splendid that her father’s seemed but a poor cottage in comparison with it, and when she recovered from her astonishment she found herself seated upon a couch, wrapped in a wonderful robe of satin fastened with a silken girdle, while beside her knelt a young man who whispered the sweetest speeches imaginable in her ear. The gnome, for he it was, told her all about himself and his great underground kingdom, and presently led her through the many rooms and halls of the palace, and showed her the rare and wonderful things displayed in them till she was fairly dazzled at the sight of so much splendour. On three sides of the castle lay a lovely garden with masses of gay, sweet flowers, and velvet lawns all cool and shady, which pleased the eye of the princess. The fruit trees were hung with golden and rosy apples, and nightingales sang in every bush, as the gnome and the princess wandered in the leafy alleys, sometimes gazing at the moon, sometimes pausing to gather the rarest flowers for her adornment. And all the time he was thinking to himself that never, during the hundreds of years he had lived, had he seen so charming a maiden. But the princess felt no such happiness; in spite of all the magic delights around her she was sad, though she tried to seem content for fear of displeasing the gnome. However, he soon perceived her melancholy, and in a thousand ways strove to dispel the cloud, but in vain. At last he said to himself: ‘Men are sociable creatures, like bees or ants. Doubtless this lovely mortal is pining for company. Who is there I can find for her to talk to?’

Thereupon he hastened into the nearest filed and dug up a dozen or so of different roots—carrots, turnips, and radishes—and laying them carefully in an elegant basket brought them to the princess, who sat pensive in the shade of the rose-bower.

‘Loveliest daughter of earth,’ said the gnome, ‘banish all sorrow; no more shall you be lonely in my dwelling. In this basket is all you need to make this spot delightful to you. Take this little many-coloured wand, and with a touch give to each root the form you desire to see.’

With this he left her, and the princess, without an instant’s delay, opened the basket, and touching a turnip, cried eagerly: ‘Brunhilda, my dear Brunhilda! come to me quickly!’ And sure enough there was Brunhilda, joyfully hugging and kissing her beloved princess, and chattering as gaily as in the old days.

This sudden appearance was so delightful that the princess could hardly believe her own eyes, and was quite beside herself with the joy of having her dear playfellow with her once more. Hand in hand they wandered about the enchanted garden, and gathered the golden apples from the trees, and when they were tired of this amusement the princess led her friend through all the wonderful rooms of the palace, until at last they came to the one in which were kept all the marvellous dresses and ornaments the gnome had given to his hoped-for bride. There they found so much to amuse them that the hours passed like minutes. Veils, girdles, and necklaces were tried on and admired, the imitation Brunhilda knew so well how to behave herself, and showed so much taste that nobody would ever have suspected that she was nothing but a turnip after all. The gnome, who had secretly been keeping an eye upon them, was very pleased with himself for having so well understood the heart of a woman; and the princess seemed to him even more charming than before. She did not forget to touch the rest of the roots with her magic wand, and soon had all her maidens about her, and even, as she had two tiny radishes to spare, her favourite cat, and her little dog whose name was Beni.

And now all went cheerfully in the castle. The princess gave to each of the maidens her task, and never was mistress better served. For a whole week she enjoyed the delight of her pleasant company undisturbed. They all sang, they danced, they played from morning to night; only the princess noticed that day by day the fresh young faces of her maidens grew pale and wan, and the mirror in the great marble hall showed her that she alone still kept her rosy bloom, while Brunhilda and the rest faded visibly. They assured her that all was well with them; but, nevertheless, they continued to waste away, and day by day it became harder to them to take part in the games of the princess, till at last, one fine morning, when the princess started from bed and hastened out to join her gay playfellows, she shuddered and started back at the sight of a group of shrivelled crones, with bent backs and trembling limbs, who supported their tottering steps with staves and crutches, and coughed dismally. A little nearer to the hearth lay the once frolicsome Beni, with all four feet stretched stiffly out, while the sleek cat seemed too weak to raise his head from his velvet cushion.

The horrified princess fled to the door to escape from the sight of this mournful company, and called loudly for the gnome, who appeared at once, humbly anxious to do her bidding.

‘Malicious Sprite,’ she cried, ‘why do you begrudge me my playmates —the greatest delight of my lonely hours? Isn’t this solitary life in such a desert bad enough without your turning the castle into a hospital for the aged? Give my maidens back their youth and health this very minute, or I will never love you!’

‘Sweetest and fairest of damsels,’ cried the gnome, ‘do not be angry; everything that is in my power I will do—but do not ask the impossible. So long as the sap was fresh in the roots the magic staff could keep them in the forms you desired, but as the sap dried up they withered away. But never trouble yourself about that, dearest one, a basket of fresh turnips will soon set matters right, and you can speedily call up again every form you wish to see. The great green patch in the garden will prove you with a more lively company.’

So saying the gnome took himself off. And the princess with her magic wand touched the wrinkled old women, and left them the withered roots they really were, to be thrown upon the rubbish heap; and with light feet skipped off across to the meadow to take possession of the freshly filled basket. But to her surprise she could not find it anywhere. Up and down the garden she searched, spying into every corner, but not a sign of it was to be found. By the trellis of grape vines she met the gnome, who was so much embarrassed at the sight of her that she became aware of his confusion while he was still quite a long way off.

‘You are trying to tease me,’ she cried, as soon as she saw him. ‘Where have you hidden the basket? I have been looking for it at least an hour.’

‘Dear queen of my heart,’ answered he, ‘I pray you to forgive my carelessness. I promised more than I could perform. I have sought all over the land for the roots you desire; but they are gathered in, and lie drying in musty cellars, and the fields are bare and desolate, for below in the valley winter reigns, only here in your presence spring is held fast, and wherever your foot is set the gay flowers bloom. Have patience for a little, and then without fail you shall have your puppets to play with.’

Almost before the gnome had finished, the disappointed princess turned away, and marched off to her own apartments, without deigning to answer him.

The gnome, however, set off above ground as speedily as possible, and disguising himself as a farmer, bought an ass in the nearest market-town, and brought it back loaded with sacks of turnip, carrot, and radish seed. With this he sowed a great field, and sent a vast army of his goblins to watch and tend it, and to bring up the fiery rivers from the heart of the earth near enough to warm and encourage the sprouting seeds. Thus fostered they grew and flourished marvellously, and promised a goodly crop.

The princess wandered about the field day by day, no other plants or fruits in all her wonderful garden pleased her as much as these roots; but still her eyes were full of discontent. And, best of all, she loved to while away the hours in a shady fir-wood, seated upon the bank of a little stream, into which she would cast the flowers she had gathered and watch them float away.

The gnome tried hard by every means in his power to please the princess and win her love, but little did he guess the real reason of his lack of success. He imagined that she was too young and inexperienced to care for him; but that was a mistake, for the truth was that another image already filled her heart. The young Prince Ratibor, whose lands joined her father’s, had won the heart of the princess; and the lovers had been looking forward to the coming of their wedding-day when the bride’s mysterious disappearance took place. The sad news drove Ratibor distracted, and as the days went on, and nothing could be heard of the princess, he forsook his castle and the society of men, and spent his days in the wild forests, roaming about and crying her name aloud to the trees and rocks. Meanwhile, the maiden, in her gorgeous prison, sighed in secret over her grief, not wishing to arouse the gnome’s suspicions. In her own mind she was wondering if by any means she might escape from her captivity, and at last she hit upon a plan.

By this time spring once more reigned in the valley, and the gnome sent the fires back to their places in the deeps of the earth, for the roots which they had kept warm through all the cruel winter hand now come to their full size. Day by day the princess pulled up some of them, and made experiments with them, conjuring up now this longed-for person, and now that, just for the pleasure of seeing them as they appeared; but she really had another purpose in view.

One day she changed a tiny turnip into a bee, and sent him off to bring her some news of her lover.

‘Fly, dear little bee, towards the east,’ said she, ‘to my beloved Ratibor, and softly hum into his ear that I love him only, but that I am a captive in the gnome’s palace under the mountains. Do not forget a single word of my greeting, and bring me back a message from my beloved.’

So the bee spread his shining wings and flew away to do as he was bidden; but before he was out of sight a greedy swallow made a snatch at him, and to the great grief of the princess her messenger was eaten up then and there.

After that, by the power of the wonderful wand she summoned a cricket, and taught him this greeting:

‘Hop, little cricket, to Ratibor, and chirp in his ear that I love him only, but that I am held captive by the gnome in his palace under the mountains.’

So the cricket hopped off gaily, determined to do his best to deliver his message; but, alas! a long-legged stork who was prancing along the same road caught him in her cruel beak, and before he could say a word he had disappeared down her throat.

These two unlucky ventures did not prevent the princess from trying once more.

This time she changed the turnip into a magpie.

‘Flutter from tree to tree, chattering bird,’ said she, ‘till you come to Ratibor, my love. Tell him that I am a captive, and bid him come with horses and men, the third day from this, to the hill that rises from the Thorny Valley.’

The magpie listened, hopped awhile from branch to branch, and then darted away, the princess watching him anxiously as far as she could see.

Now Prince Ratibor was still spending his life in wandering about the woods, and not even the beauty of the spring could soothe his grief.

One day, as he sat in the shade of an oak tree, dreaming of his lost princess, and sometimes crying her name aloud, he seemed to hear another voice reply to his, and, starting up, he gazed around him, but he could see no one, and he had just made up his mind that he must be mistaken, when the same voice called again, and, looking up sharply, he saw a magpie which hopped to and fro among the twigs. Then Ratibor heard with surprise that the bird was indeed calling him by name.

‘Poor chatterpie,’ said he; ‘who taught you to say that name, which belongs to an unlucky mortal who wishes the earth would open and swallow up him and his memory for ever?’

Thereupon he caught up a great stone, and would have hurled it at the magpie, if it had not at that moment uttered the name of the princess.

This was so unexpected that the prince’s arm fell helplessly to his side at the sound, and he stood motionless.

But the magpie in the tree, who, like all the rest of his family, was not happy unless he could be for ever chattering, began to repeat the message the princess had taught him; and as soon as he understood it, Prince Ratibor’s heart was filed with joy. All his gloom and misery vanished in a moment, and he anxiously questioned the welcome messenger as to the fate of the princess.

But the magpie knew no more than the lesson he had learnt, so he soon fluttered away; while the prince hurried back to his castle to gather together a troop of horsemen, full of courage for whatever might befall.

The princess meanwhile was craftily pursuing her plan of escape. She left off treating the gnome with coldness and indifference; indeed, there was a look in her eyes which encouraged him to hope that she might some day return his love, and the idea pleased him mightily. The next day, as soon as the sun rose, she made her appearance decked as a bride, in the wonderful robes and jewels which the fond gnome had prepared for her. Her golden hair was braided and crowned with myrtle blossoms, and her flowing veil sparkled with gems. In these magnificent garments she went to meet the gnome upon the great terrace.

‘Loveliest of maidens,’ he stammered, bowing low before her, ‘let me gaze into your dear eyes, and read in them that you will no longer refuse my love, but will make me the happiest being the sun shines upon.’

So saying he would have drawn aside her veil; but the princess only held it more closely about her.

‘Your constancy has overcome me,’ she said; ‘I can no longer oppose your wishes. But believe my words, and suffer this veil still to hide my blushes and tears.’

‘Why tears, beloved one?’ cried the gnome anxiously; ‘every tear of yours falls upon my heart like a drop of molten gold. Greatly as I desire your love, I do not ask a sacrifice.’

‘Ah!’ cried the false princess, ‘why do you misunderstand my tears? My heart answers to your tenderness, and yet I am fearful. A wife cannot always charm, and though YOU will never alter, the beauty of mortals is as a flower that fades. How can I be sure that you will always be as loving and charming as you are now?’

‘Ask some proof, sweetheart,’ said he. ‘Put my obedience and my patience to some test by which you can judge of my unalterable love.’

‘Be it so,’ answered the crafty maiden. ‘Then give me just one proof of your goodness. Go! count the turnips in yonder meadow. My wedding feast must not lack guests. They shall provide me with bride-maidens too. But beware lest you deceive me, and do not miss a single one. That shall be the test of your truth towards me.’

Unwilling as the gnome was to lose sight of his beautiful bride for a moment, he obeyed her commands without delay, and hurried off to begin his task. He skipped along among the turnips as nimble as a grasshopper, and had soon counted them all; but, to be quite certain that he had made no mistake, he thought he would just run over them again. This time, to his great annoyance, the number was different; so he reckoned them for the third time, but now the number was not the same as either of the previous ones! And this was hardly to be wondered at, as his mind was full of the princess’s pretty looks and words.

As for the maiden, no sooner was her deluded lover fairly out of sight than she began to prepare for flight. She had a fine fresh turnip hidden close at hand, which she changed into a spirited horse, all saddled and bridled, and, springing upon its back, she galloped away over hill and dale till she reached the Thorny Valley, and flung herself into the arms of her beloved Prince Ratibor.

Meanwhile the toiling gnome went through his task over and over again till his back ached and his head swam, and he could no longer put two and two together; but as he felt tolerably certain of the exact number of turnips in the field, big and little together, he hurried back eager to prove to his beloved one what a delightful and submissive husband he would be. He felt very well satisfied with himself as he crossed the mossy lawn to the place where he had left her; but, alas! she was no longer there.

He searched every thicket and path, he looked behind every tree, and gazed into every pond, but without success; then he hastened into the palace and rushed from room to room, peering into every hole and corner and calling her by name; but only echo answered in the marble halls—there was neither voice nor footstep.

Then he began to perceive that something was amiss, and, throwing off the mortal form that encumbered him, he flew out of the palace, and soared high into the air, and saw the fugitive princess in the far distance just as the swift horse carried her across the boundary of his dominions.

Furiously did the enraged gnome fling two great clouds together, and hurl a thunderbolt after the flying maiden, splintering the rocky barriers which had stood a thousand years. But his fury was vain, the thunderclouds melted away into a soft mist, and the gnome, after flying about for a while in despair, bewailing to the four winds his unhappy fate, went sorrowfully back to the palace, and stole once more through every room, with many sighs and lamentations. He passed through the gardens which for him had lost their charm, and the sight of the princess’s footprints on the golden sand of the pathway renewed his grief. All was lonely, empty, sorrowful; and the forsaken gnome resolved that he would have no more dealings with such false creatures as he had found men to be.

Thereupon he stamped three times upon the earth, and the magic palace, with all its treasures, vanished away into the nothingness out of which he had called it; and the gnome fled once more to the depths of his underground kingdom.

While all this was happening, Prince Ratibor was hurrying away with his prize to a place of safety. With great pomp and triumph he restored the lovely princess to her father, and was then and there married to her, and took her back with him to his own castle.

But long after she was dead, and her children too, the villagers would tell the tale of her imprisonment underground, as they sat carving wood in the winter nights.

Volksmahrchen der Deutschen.

Rübezahl

Lo gnomo di montagna Rubezhal era il signore di tutto il vasto mondo sotterraneo ed era abbastanza occupato a prendersi cura dei suoi domini. C’erano le infinite camere del tesoro da attraversare e gli ospiti degli gnomi da seguire nelle loro mansioni. Alcuni costruivano robuste barriere per contenere i vapori fiammeggianti che mutavano le smorte pietre in metallo prezioso, o era duro lavorare riempiendo ogni crepa delle rocce con diamanti e rubini, perché Rubezhal amava tutte queste piccole cose. A volte lo prendeva il ghiribizzo di abbandonare quelle tenebrose regioni e salire sulla verde terra per un po’ e crogiolarsi al sole e udire il canto degli uccelli. E siccome gli gnomi vivono per molte centinaia di anni, aveva visto cose strane. Per esempio, la prima volta in cui era risalito, le grandi colline erano coperte di folte foreste nelle quali vagavano animali selvatici e Rubezhal aveva visto le feroci lotte tra l’orso e il bisonte o aveva dato la caccia ai lupi grigi o si era divertito a far rotolare grosse rocce giù per le valli desolate per sentire il fragore della loro caduta echeggiare tra le colline. Ma la volta successiva in cui si avventurò sulla terra, quale fu la sua sorpresa nel vedere tutto mutato! Le oscure foreste erano state abbattute e al loro posto erano comparsi frutteti in fiore che circondavano casette con i tetti di paglia dall’aspetto confortevole; da ogni camino il fumo azzurro si avvolgeva quietamente nell’aria, pecore e mucche pascolavano nei prati fioriti mentre dall’ombra delle siepi proveniva la musica degli zufoli dei pastori. La stranezza e il piacere di quella vista piacque tanto allo gnomo che non gli venne mai in mente di risentirsi per l’intrusione di quegli inaspettati ospiti i quali, senza dire “con il vostro permesso” si comportavano come se fossero a casa loro sulle sue colline; né desiderò interferire con i loro affari ma li lasciò tranquillamente in possesso delle loro case come un buon padrone di casa lascia in pace le rondini che hanno costruito i loro nidi sotto i suoi cornicioni. Gli sarebbe piaciuto molto fare amicizia con questi cosiddetti ‘uomini’ così, assumendo l’aspetto di un vecchio contadino, si mise al servizio di un agricoltore. Sotto le sue cure tutti raccolti maturarono straordinariamente, ma il padrone dimostrò di essere sciupone e ingrato e Rubezhal lo lasciò e divenne pastore presso il suo vicino. Custodiva le greggi con tale diligenza e sapeva bene dove condurre le pecore ai pascoli più dolci, e dove cercare tra le colline qualunque di essa si allontanasse, che anche le greggi prosperarono sotto le sue cure e non un solo animale andò perduto o fu dilaniato dai lupi; però questo nuovo padrone era un uomo duro ed era riluttante a pagargli il ben meritato salario. Così se ne andò e si mise al servizio del giudice. Qui difese la legge con energia e con forza ed era il terrore dei ladri e dei malfattori, ma il giudice era un uomo cattivo, che si faceva corrompere e disprezzava la legge. Rubezhal non avrebbe voluto essere lo strumento di un uomo iniquo, così lo disse al padrone il quale a quel punto ordinò che fosse gettato in prigione. Naturalmente ciò non comportò nessun disagio allo gnomo, che semplicemente uscì attraverso il buco della serratura e tornò nel suo palazzo sotterraneo assai sbigottito da questa sua prima esperienza con l’umanità. Ma con il passare del tempo dimenticò tutte le sgradevoli cose che gli erano capitate e pensò di andare a dare un’altra occhiata al mondo di sopra.

Così sgattaiolò nella valle, badando bene di nascondersi nella macchia o tra le siepi, e ben presto incappò in un’avventura; perché, spiando dietro lo schermo delle foglie, vide davanti a sé un prato verde sul quale c’era un’affascinante fanciulla, fresca come la primavera e bellissima da osservare. sull’erba intorno a lei c’erano le sue giovani compagne, come si fossero sdraiate lì a riposare dopo qualche allegro gioco. Più in là rispetto a loro scorreva un torrentello nel quale una cascata si gettava da un’alta roccia, riempiendo l’aria di un suono gradevole e rinfrescando persino l’afoso mezzogiorno.

La vista della fanciulla compiacque tanto lo gnomo che, per la prima volta, desiderò di essere un mortale; desiderando vedere meglio l’allegra brigata, si tramutò in un corvo e si appollaiò su una quercia che sovrastava il ruscello. Ben presto però si accorse che non fosse per niente un buon piano. Poteva vedere solo con gli occhi di un corvo e avere i sentimenti di un corvo; un nido di topolini di campagna ai piedi dell’albero lo interessava più del gioco delle ragazze. Quando lo comprese, volò di nuovo in gran fretta nel folto del bosco e prese l’aspetto di un affascinante giovane – la cosa migliore – e s’innamorò all’istante della ragazza. La bella fanciulla era la figlia del re del paese e spesso si aggirava per la foresta con le compagne di giochi per raccogliere fiori e frutti selvatici finché il calore del mezzogiorno non conduceva l’allegra brigata sul prato ombreggiato vicino al ruscello per riposare o fare il bagno nell’acqua fresca. Proprio quella mattina le aveva prese la voglia di vagabondare di nuovo per il bosco. E questa fu l’occasione per padron Rubezhal. Sgattaiolando dal proprio nascondiglio, si mise al centro del piccolo prato, pronunciando gli incantesimi, finché lentamente tutto intorno a lui cambiò e, quando le ragazze a mezzogiorno tornarono nel loro posto di riposo preferito, restarono sbalordite e credettero che dovesse trattarsi di un sogno. Le rocce rosse erano diventate marmo bianco e alabastro, il ruscello che prima gorgogliava e scorreva sul letto pietroso ora fluiva silenzioso nel suo alveo levigato, dal quale si ergeva una limpida fontana, per cadere di nuovo in una pioggia di gocce diamantine, ora da un lato, ora dall’altro, secondo il soffio della brezza.

Margherite e nontiscordadimè orlavano le sue rive mentre alte siepi di rose e di gelsomini correvano all’intorno, creando il pergolato più dolce e delicato che si potesse immaginare. A destra e a sinistra della cascata si apriva un’invitante grotta i cui muri e archi luccicavano di cristalli di vari colori mentre da ogni nicchia spuntavano strani frutti e dolci, la cui sola vista fece desiderare alla principessa di assaggiarli. Esitò un po’, in ogni modo, perché credeva a malapena ai propri occhi, e non sapeva se dovesse entrare in quel luogo incantato o fuggirne. Alla fine però la curiosità ebbe la meglio e lei e le sue compagne esplorarono volentieri, assaggiando ed osservando ogni cosa, correndo qua e là con grande gioia e chiamandosi l’un l’altra allegramente.

Alla fine, quando furono completamente stanche, la principessa esclamò improvvisamente che nulla l’avrebbe fatta più contenta di fare il bagno nella vasca di marmo che certamente appariva assai invitante; e tutte si diressero allegramente verso questo nuovo divertimento. La principessa fu pronta per prima, ma era appena scivolata oltre il bordo della vasca che sprofondò giù, sempre più giù, e svanì sul fondo prima che le atterrite compagne di gioco potessero afferrare neppure una ciocca dei suoi fluttuanti capelli d’oro!

Piansero e gemettero ad alta voce, correndo intorno al bordo della vasca che sembrava così poco profonda e limpida, ma che aveva inghiottito la principessa sotto i loro occhi. Si gettarono persino in acqua e tentarono di immergersi dietro di lei, ma invano; poterono solo galleggiare come turaccioli nella vasca incantata e neppure per un secondo andarono sott’acqua.

Alla fine si resero conto che non c’era niente altro da fare se non portare al re la triste notizia della sparizione della sua amata figlia. Quanti pianti e lamenti si levarono nel palazzo quando fu riferita la terribile notizia! Il re si strappò le vesti, si tolse la corona d’oro dalla testa e nascose il volto nel mantello di porpora per il dolore e l’angoscia della perdita della principessa. Dopo il primo scoppio di lamenti, in ogni modo, si fece animo e si affrettò a vedere con i propri occhi la scena di questa strana avventura, pensando, come qualsiasi persona addolorata, che dopotutto dovesse trattarsi solo di un errore. Ma quando ebbe raggiunto il luogo, guarda un po’, tutto era cambiato di nuovo! La grotta scintillante descrittagli dalle ragazze era completamente svanita e così la vasca di marmo e il pergolato di gelsomini; invece era tutto un groviglio di fiori come se fossero appassiti. Il re fu così perplesso che minaccio le compagne di gioco della figlia con ogni sorta di castighi se non avessero confessato qualcosa sulla sua sparizione, ma siccome loro ripetevano solo la stessa storia, egli attribuì tutta la faccenda all’operato di qualche elfo o spiritello maligno e tentò di consolarsi della perdita ordinando una grande battuta di caccia perché i re non possono sopportare di restate addolorati a lungo per qualcosa.

Nel frattempo la principessa non era del tutto infelice nel palazzo del suo innamorato fatato.

Quando le ninfe d’acqua, che erano nascoste all’erta, l’avevano afferrata e trascinata via dalla vista delle sue atterrite damigelle, non aveva avuto il tempo di impaurirsi. Nuotavano rapidamente con lei attraverso strane vie sotterranee verso un palazzo così splendido al confronto del quale quello di suo padre sembrava una povera capanna e quando si fu ripresa dallo stupore, si ritrovò seduta in una carrozza, avvolta di un meraviglioso abito di raso trattenuto da una cintura di seta mentre al suo fianco era inginocchiato un giovane che le sussurrava all’orecchio le più dolci parole che si potessero immaginare. Lo gnomo, perché di lui si trattava, le narrò tutto di sé e del grande regno sotterraneo e la condusse subito attraverso le molte stanze e sale del palazzo e le mostrò le cose rare e meravigliose che vi erano esposte finché lei fu abbagliata alla vista di tale splendore. Intorno a tre lati del castello c’era un delizioso giardino con una gran quantità di fiori allegri e dolci, e prati vellutati freschi e ombreggiati che furono graditi agli occhi della principessa. Dagli alberi da frutto pendevano mele dorate e rosate e gli usignoli cantavano in ogni cespuglio, così lo gnomo e la principessa camminavano lungo i viali frondosi, a volte ammirando la luna, a volte fermandosi a raccogliere i fiori perché lei se ne adornasse. E per tutto il tempo continuò a pensare tra sé che mai, durante le centinaia di anni in cui aveva vissuto, aveva visto una ragazza così affascinante. Ma la principessa non era felice; malgrado tutte le magiche delizie che la circondavano, era triste, sebbene tentasse di sembrare contenta per timore di dispiacere allo gnomo. In ogni modo lui si accorse ben presto della sua malinconia e tentò invano in migliaia di modi di dissiparla. Alla fine si disse: ‘Gli uomini sono creature socievoli come le api o le formiche. Senza dubbio questa deliziosa mortale anela compagnia. Chi potrei trovare qui che parlasse con lei?’ A quel punto andò in fretta nel campo più vicino ed estrasse una dozzina o giù di lì delle radici più diverse… carote, rape e ravanelli, e deponendoli con cura in un elegante canestro le portò alla principessa, che sedeva pensierosa all’ombra di un pergolato di rose.

“Leggiadrissima figlia della terra,” disse lo gnomo “allontana la tristezza, non sarai più sola nella mia dimora. In questo canestro c’è tutto ciò di cui hai bisogno per rendere delizioso per te questo luogo. Prendi questa piccola bacchetta multicolore e con un tocco dai a ciascuna radice la forma che desideri vedere.”

Con queste parole gliela lasciò e la principessa, senza un attimo di esitazione, aprì il canestro e, toccando una rapa, esclamò con ardore: “Brunhilda, mia cara Brunhilda! Vieni presto da me!” E naturalmente ecco Brunhilda, che abbracciava e baciata la sua amata principessa e chiacchierava allegramente come ai vecchi tempi.

Questa subitanea apparizione fu così piacevole che la principessa a malapena credeva ai propri occhi e fu quasi sopraffatta dalla gioia di avere ancora una volta con sé la cara compagna di giochi. Mano nella mano si aggirarono per il giardino incantato e raccolsero le mele dorate dagli alberi poi, quando furono stanche di questo divertimento, la principessa condusse l'amica per le meravigliose stanze del palazzo finché alla fine giunsero in quella in cui erano conservati tutti i meravigliosi abiti e ornamenti che lo gnomo aveva dato alla fanciulla che sperava di sposare. Lì si divertirono tanto che le ore trascorsero come minuti. Veli, cinture e collane furono presi e ammirati, la finta Brunhilde sapeva bene comportarsi così bene e mostrava tanto buongusto che nessuno avrebbe mai sospettato dopotutto non fosse altro che una rapa. Lo gnomo, che le teneva d'occhio segretamente, si compiacque molto con se stesso per aver così ben compreso il cuore di una donna; e la principessa gli sembrava più affascinante di prima. Lei non dimenticò di toccare le altre radici con la bacchetta magica e ben presto ebbe tutte le compagne con sé e persino, siccome aveva tenuto da parte due piccoli ravanelli, il il suo gatto preferito e il cagnolino di nome Beni.

Adesso al castello era tutta gioia. La principessa diede un compito a ciascuna delle damigelle e mai dama fu servita meglio. Per un'intera settimana godette indisturbata la delizia della piacevole compagnia. Cantavano, danzavano, giocavano dalla mattina alla sera, solo la principessa si accorse che di giorno in giorno i volti giovani e freschi delle sue damigelle diventavano pallidi e languidi e lo specchio nel grande salone di marmo le mostrava che lei sola era rosea mentre Brunhilda e le altre sbiadivano visibilmente. Le assicuravano che per loro tutto andava bene ma, tuttavia, continuavano a deperire e, giorno dopo giorno, diventava più difficile per loro prender parte ai giochi della principessa finché alla fine, una mattina, quando la principessa si alzò dal letto e si affrettò ad incontrare le allegre compagne di gioco, rabbrividì e arretrò alla vista di un gruppo di vecchie avvizzite, con le spalle curve e le membra tremanti, che sostenevano i passi vacillanti con bastoni e stampelle e tossivano orribilmente. Un poco più vicino al focolare giaceva Beni, una volta allegro, con tutte e quattro le zampe stese rigidamente, mentre il gatto sembrava troppo debole per sollevare la testa dal cuscino di velluto.

Inorridita, la principessa si slanciò verso la porta per sfuggire alla vista di questa lugubre compagnia e chiamò a gran voce lo gnomo, che comparve subito, umilmente ansioso di ubbidire ai suoi comandi.

“Malvagio folletto,” gridò lei “perché mi hai concesso con riluttanza le mie compagne di gioco… la più grande gioia delle mie ore malinconiche? Questa vita solitaria in un simile deserto non è abbastanza sgradevole senza che tu trasformi il castello in un ospizio per anziani? Restituisci all’istante la bellezza e la salute alle mie damigelle o non ti amerò mai!”

"O dolcissima e bellissima tra le dame," esclamò lo gnomo "non essere adirata; farò qualunque cosa sia in mio potere... ma non chiedermi l'impossibile. Finché la linfa era fresca nelle radici, l'effetto magico le manteneva nelle forme che tu desideravi, ma come la linfa si è seccata, esse sono incanutite. Non dartene pena, carissima, ti sarà dato un canestro di rape fresche e tu potrai subito richiamare qualsiasi forma desideri. Il grande spiazzo verde nel giardino si rivelerà per te una compagnia più briosa.

Così dicendo lo gnomo se ne andò. E la principessa con la sua bacchetta magica toccò le vecchie grinzose e lasciò che tornassero le radici biancastre che erano, pronte per essere gettate nel mucchio della spazzatura; con passo leggero corse attraverso il prato per impossessarsi del canestro riempito con quelle fresche. Ma con sua sorpresa non lo trovò da nessuna parte. Lo cercò su e giù per il giardino, sbirciando in ogni angolo, ma non ne trovò alcuna traccia. Vicino ai graticci d'uva incontrò lo gnomo, il quale fu così imbarazzato vedendola che lei si accorse della sua confusione mentre era ancora abbastanza lontana.

"Stai cercando di prendermi in giro." gridò, appena lo vide "Dove hai nascosto il canestro? L'ho cercato almeno per un'ora."

"Amata regina del mio cuore," rispose lo gnomo "ti prego di perdonare la mia negligenza. Ti ho promesso più di quanto potessi mantenere. Ho cercato le radici che desideri in tutta la terra, ma sono state raccolte e ora giacciono a seccare in vecchie cantine e i campi sono nudi e desolati perché giù a valle regna l'inverno; solo qui alla tua presenza la primavera si mantiene e ovunque il tuo piede si posi, sbocciano allegri fiori. Abbi pazienza per un po' e allora certamente avrai i tuoi pupazzi per trastullarti."

Prima che lo gnomo avesse finito, la principessa se ne andò delusa e si diresse verso i propri appartamenti senza degnarlo di una risposta.

In ogni modo lo gnomo si mise in cammino più in fretta che poté e, camuffandosi da contadino, comprò un asino nel mercato più vicino e lo riportò in dietro carico di sacchi di semi di rape, carote e ravanelli. Con essi seminò un vasto campo e mandò una folta schiera di folletti a sorvegliarlo e a curarlo e a deviare in alto gli impetuosi fiumi dal cuore della terra abbastanza vicino da poter scaldare e favorire la fioritura dei semi. Così coltivati, crebbero e germogliarono meravigliosamente e promettevano un ottimo raccolto.

La principessa gironzolava per il campo giorno dopo giorno, in tutto il meraviglioso giardino nessun altra pianta o albero da frutto le piaceva tanto quanto quelle radici; eppure i suoi occhi erano ancora pieni di scontentezza. E soprattutto lei amava trascorrere le ore in un ombreggiato bosco di abeti, seduta in riva a un ruscello in cui gettava i fiori che aveva raccolto e guardandoli fluttuare.

Lo gnomo tentava con tutte le forze e con ogni mezzo in suo potere di compiacere la principessa e conquistare il suo amore, ma supponeva scarsamente la ragione del proprio fallimento. Immaginava che la principessa fosse troppo giovane e inesperta per curarsi di lui, ma si sbagliava perché la verità era che un'altra persona aveva già occupato il suo cuore. Il giovane principe Ratibor, le cui terre confinavano con quelle di suo padre, aveva conquistato il cuore della principessa; gli innamorati attendevano con impazienza il giorno delle nozze quando era avvenuta la misteriosa sparizione della promessa sposa. La triste notizia sconvolse Ratibor e siccome i giorni passavano e non c'erano notizie della principessa, aveva abbandonato il proprio castello e la società civile e trascorreva i giorni nelle foreste selvagge, vagando e gridando il suo nome agli alberi e alle rocce. Nel frattempo la ragazza, nella sua fastosa prigione, sospirava in segreto sul proprio dolore, non volendo suscitare i sospetti dello gnomo. Dentro di sé cercava il modo per poter scappare dalla prigionia e alla fine ideò un piano.

A quel punto la primavera regnava ancora una volta nella valle e lo gnomo aveva rimandato il calore nel cuore della terra perché le radici che ne avevano beneficiato durante il rigido inverno adesso erano nel pieno rigoglio. Giorno dopo giorno la principessa ne prendeva un po' e faceva esperimenti con esse, evocando ora una persona cara ora quella, solo per il piacere di vedere come apparivano, ma in effetti aveva in mente un altro scopo.

Un giorno mutò una piccola rapa in un'ape e la mandò via perché le portasse notizie del suo amore.

"Vola verso est, piccola cara ape, " disse "dal mio amato Ratibor e sussurragli dolcemente all'orecchio che amo solo lui ma che sono prigioniera nel palazzo dello gnomo sotto le montagne. Non dimenticare una sola delle mie parole e riportami un messaggio dal mio amato."

Così l'ape spiegò le alucce scintillanti e volò via per fare ciò che le era stato ordinato, ma, prima che fosse sparita dalla vista della principessa, una rondine ingorda la ghermì e con gran dolore della principessa la sua messaggera fu mangiata là per là.

Dopo un po', grazie al potere della meravigliosa bacchetta, evocò un grillo e gli impartì queste istruzioni:

"Salta da Ratibor, piccolo grillo, e frinisci nel suo orecchio che amo solo lui, ma che sono tenuta prigioniera dallo gnomo nel suo palazzo sotto le montagne."

Così il grillo saltò via vivacemente, deciso a a far del proprio meglio per consegnare il messaggio, ma, ahimè! Una cicogna dalle lunghe zampe, che stava percorrendo la medesima strada, lo afferrò con il becco crudele e prima che il grillo potesse dire una sola parola, era sparito nella sua gola.

Queste due sfortunate vicende non impedirono alla principessa di tentare ancora una volta.

Stavolta tramutò la rapa in una gazza.

"Vola di albero in albero, uccello chiacchierino," disse la principessa "finché raggiungerai Ratibor, il mio amore. Digli che sono prigioniera e invitalo a venire con uomini e cavalli il terzo giorno a partire da oggi presso la collina che si erge nella Valle Spinosa."

La gazza ascoltò, balzò da un ramo all'altro e poi si lanciò, mentre la principessa la guardava ansiosamente finché poté vederla.

Ora il principe Ratibor stava ancora sprecando la vita a vagabondare per i boschi e neppure la bellezza della primavera poteva lenire il suo dolore.

Un giorno, mentre sedeva all'ombra di una quercia, sognando la sua principessa perduta e gridando a volte il suo nome, gli sembrò di sentire un'altra voce rispondergli e, alzandosi, si guardò attorno, ma non poté vedere nessuno; si era appena convinto di essersi sbagliato quando la medesima voce lo chiamò di nuovo e, guardando su all'improvviso, vide una gazza che saltellava qua e là tra i rami. Allora Ratibor sentì con sorpresa che l'uccello stava proprio chiamandolo per nome.

"Povera gazza chiacchierona," disse, "chi pensa che tu pronunci quel nome, che appartiene a uno sfortunato mortale che desidera la terra si apra e lo inghiotta per sempre con i suoi ricordi?"

A quel punto afferrò una grossa pietra e l’avrebbe scagliata contro la gazza se in quel momento non avesse detto il nome della principessa.

Ciò fu così inaspettato che il braccio del principe a quel suono cadde debolmente lungo il fianco ed egli restò immobile.

Ma la gazza sull’albero la quale, come il resto della sua famiglia non era contenta a meno che non potesse chiacchierare sempre, cominciò a ripetere il messaggio che la principessa le aveva insegnato; appena ebbe compreso, il cuore del principe Ratibor si colò di gioia. Tutta la malinconia e l’infelicità sparirono in un momento e interrogò ansiosamente il gradito messaggero sulla sorte della principessa.

Ma la gazza non conosceva altro che la lezione imparata, così ben presto volò via, mentre il principe si affrettò a tornare al castello per radunare le truppe dei cavalieri, pieno di coraggio verso qualsiasi cosa sarebbe accaduta.

Nel frattempo la principessa stava astutamente perseguendo il proprio piano di fuga. Smise di trattare lo gnomo con freddezza e indifferenza; al contrario, c’era un’espressione nei suoi occhi che lo incoraggiava a sperare che un giorno lei potesse ricambiare il suo amore e l’idea gli piacque enormemente. Il giorno successivo, appena sorto il sole, lei comparve vestita da sposa con il meraviglioso abbigliamento e i gioielli che l’appassionato gnomo aveva preparato per lei. I capelli biondi erano intrecciati e coronati di boccioli di mirto e il velo fluttuante brillava di gemme. In questo magnifico abbigliamento andò incontro allo gnomo sulla terrazza grande.

“Leggiadrissima tra le fanciulle,” balbettò lo gnomo, inchinandosi profondamente davanti a lei “lascia che io fissi i tuoi cari occhi e vi legga che non rifiuterai più a lungo il mio amore, ma che farai di me la creatura più felice sotto il sole.”

Così dicendo, avrebbe voluto scostare il velo, ma la principessa lo tenne più distante da sé.

“La tua perseveranza mi ha vinta,” disse “non posso oppormi più a lungo ai tuoi desideri. Ma, credimi e lascia che questo velo nasconda il mio rossore e le mie lacrime.”

“perché lacrime, mia amata?” gridò lo gnomo ansiosamente “Ognuna delle tue lacrime cade sul mio cuore come una goccia di oro fuso. Per quanto grandemente desideri il tuo amore, non ti chiedo un sacrificio.”

“Perché fraintendi le mie lacrime?” esclamò l’ipocrita principessa “Il mio cuore risponde alla tua amorevolezza e tuttavia io sono impaurita. Una moglie non può essere sempre affascinante e sebbene TU non cambierai mai, la bellezza dei mortali e come un fiore che appassisce. Come posso essere certa che tu sarai sempre innamorato e adorabile come sei ora?”

“Chiedimi una prova, tesoro,” disse lo gnomo. “Sottoponi la mia obbedienza e la mia pazienza a qualsiasi prova dalla quale tu possa giudicare il mio immutabile amore.”

“E così sia.” rispose la scaltra fanciulla. “Allora dammi solo una prova della tua bontà. Vai e conta le rape nel campo laggiù. La mia festa di nozze non deve essere priva di ospiti. Essi mi forniranno anche le damigelle. Ma bada di non deludermi e non dimenticare uno solo. Questa sarà la prova della tua sincerità verso di me.”

Sebbene lo gnomo fosse riluttante a perdere di vista la splendida sposa anche per un solo momento, obbedì senza indugio al suo ordine e si affrettò a svolgere il compito. Si sposto velocemente tra le rape come una cavalletta e ben presto le ebbe contate tutte; tuttavia per essere certo di non fare errori, pensò di correre di nuovo a contarle. Stavolta con suo grande fastidio il numero era diverso, così le contò per la terza volta, ma adesso il numero non era il medesimo né dell’una né dell’altra delle volte precedenti! Ed è difficile non stupirsene, visto che la sua mente era piena della vista e delle parole della bella principessa.

Quanto alla ragazza, appena l’innamorato ingannato fu scomparso dalla sua vista, si preparò alla fuga. Aveva nascosta a portata di mano una bella rapa fresca che trasformò in un focoso cavallo, con tanto di sella e briglie, e, balzandogli in groppa, cavalcò via oltre le colline finché giunse nella Valle Spinosa e si gettò fra le braccia dell’amato principe Ratibor.

Nel frattempo quello sgobbone dello gnomo continuava ancora e ancora la sua prova al punto che la schiena gli doleva e la testa gli girava e non sarebbe riuscito neppure a fare due più due, ma siccome si sentiva abbastanza sicuro del numero esatto di rape nel campo, piccole e grandi insieme, si affrettò a tornare indietro, desideroso di provare alla sua amata che marito delizioso e remissivo sarebbe stato. Si sentiva molto soddisfatto di sé mentre attraversava il prato muschioso diretto verso il luogo in cui aveva lasciato la principessa; ma, ahimè! lei non era più lì.

La cercò in ogni boschetto e sentiero, guardò dietro gli alberi e dentro ogni stagno, ma senza successo; allora si affrettò a tornare nel palazzo e corse da una stanza all’altra, sbirciando in ogni buco e in ogni angolo e chiamandola per nome, ma nelle stanze di marmo rispondeva solo l’eco… non c’erano né voci né passi.

Allora cominciò a intuire che qualcosa non andasse e, abbandonando l’aspetto umano che lo intralciava, si slanciò fuori dal palazzo e si librò in alto nel cielo; vide così in lontananza la principessa fuggitiva proprio mentre il veloce cavallo la portava oltre il confine dei suoi domini.

L’adirato gnomo scagliò furiosamente due nubi l’una contro l’altra e lanciò un fulmine davanti alla fanciulla in corsa, frantumando le barriere rocciose che si ergevano da migliaia di anni. Ma la sua collera fu vana, il fulmine si disperse in una soffice nebbia e lo gnomo, dopo aver volato ancora un po’ disperato, lamentandosi con i quattro venti per il proprio infelice destino, tornò addolorato a palazzo e guardò ancora una volta furtivamente in ogni stanza, con molti sospiri e lamenti. Passò per i giardini che avevano perso il loro fascino e la vista delle orme della principessa sulla sabbia dorata del sentiero ravvivò il suo dolore. Tutto era solitudine, vuoto, dolore e il derelitto gnomo decise che non si sarebbe più occupate di quelle creature false che aveva scoperto essere gli umani.

A quel punto batté tre volte per terra e il magico palazzo con tutti i suoi tesori svanì nel nulla dal quale era venuto; lo gnomo fuggì ancora una volta nelle profondità del suo regno sotterraneo.

Mentre accadeva tutto ciò, il principe Ratibor si stava affrettando con il suo premio verso una meta sicura. Con grande sfarzo e tripudio restituì al padre la graziosa principessa, l’ebbe subito in moglie e la portò con sé nel proprio castello.

Dopo molto tempo dalla sua morte e da quella dei suoi figli, gli abitanti del villaggio narravano la storia della sua prigionia sotterranea mentre sedevano a intagliare il legno nelle notti d’inverno.

Fiaba popolare tedesca.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)