One hot night, in Hindustan, a king and queen lay awake in the palace in the midst of the city. Every now and then a faint air blew through the lattice, and they hoped they were going to sleep, but they never did. Presently they became more broad awake than ever at the sound of a howl outside the palace.

‘Listen to that tiger!’ remarked the king.

‘Tiger?’ replied the queen. ‘How should there be a tiger inside the city? It was only a jackal.’

‘I tell you it was a tiger,’ said the king.

‘And I tell you that you were dreaming if you thought it was anything but a jackal,’ answered the queen.

‘I say it was a tiger,’ cried the king; ‘don’t contradict me.’

‘Nonsense!’ snapped the queen. ‘It was a jackal.’ And the dispute waxed so warm that the king said at last:

‘Very well, we’ll call the guard and ask; and if it was a jackal I’ll leave this kingdom to you and go away; and if it was a tiger then you shall go, and I will marry a new wife.’

‘As you like,’ answered the queen, ‘there isn’t any doubt which it was.’

So the king called the two soldiers who were on guard outside and put the question to them. But, whilst the dispute was going on, the king and queen had got so excited and talked so loud that the guards had heard nearly all they said, and one man observed to the other:

‘Mind you declare that the king is right. It certainly was a jackal, but, if we say so, the king will probably not keep his word about going away, and we shall get into trouble, so we had better take his side.’

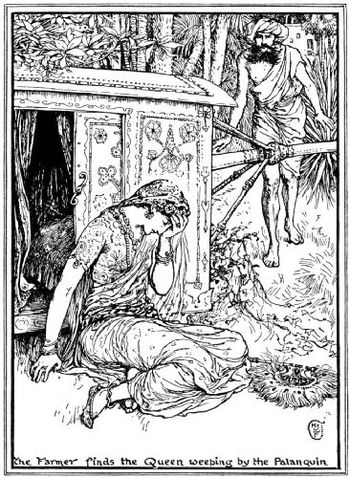

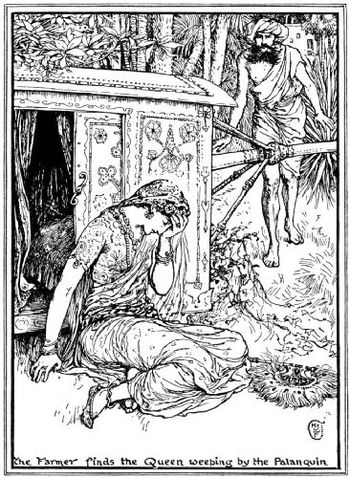

To this the other agreed; therefore, when the king asked them what animal they had seen, both the guards said it was certainly a tiger, and that the king was right of course, as he always was. The king made no remark, but sent for a palanquin, and ordered the queen to be placed in it, bidding the four bearers of the palanquin to take her a long way off into the forest and there leave her. In spite of her tears, she was forced to obey, and away the bearers went for three days and three nights until they came to a dense wood. There they set down the palanquin with the queen in it, and started home again.

Now the queen thought to herself that the king could not mean to send her away for good, and that as soon as he had got over his fit of temper he would summon her back; so she stayed quite still for a long time, listening with all her ears for approaching footsteps, but heard none. After a while she grew nervous, for she was all alone, and put her head out of the palanquin and looked about her. Day was just breaking, and birds and insects were beginning to stir; the leaves rustled in a warm breeze; but, although the queen’s eyes wandered in all directions, there was no sign of any human being. Then her spirit gave way, and she began to cry.

It so happened that close to the spot where the queen’s palanquin had been set down, there dwelt a man who had a tiny farm in the midst of the forest, where he and his wife lived alone far from any neighbours. As it was hot weather the farmer had been sleeping on the flat roof of his house, but was awakened by the sound of weeping. He jumped up and ran downstairs as fast as he could, and into the forest towards the place the sound came from, and there he found the palanquin.

Oh, poor soul that weeps,’ cried the farmer, standing a little way off, ‘who are you?’ At this salutation from a stranger the queen grew silent, dreading she knew not what.

‘Oh, you that weep,’ repeated the farmer, ‘fear not to speak to me, for you are to me as a daughter. Tell me, who are you?’

His voice was so kind that the queen gathered up her courage and spoke. And when she had told her story, the farmer called his wife, who led her to their house, and gave her food to eat, and a bed to lie on. And in the farm , a few days later, a little prince was born, and by his mother’s wish named Ameer Ali.

Years passed without a sign from the king. His wife might have been dead for all he seemed to care, though the queen still lived with the farmer, and the little prince had by this time grown up into a strong, handsome, and healthy youth. Out in the forest they seemed far from the world; very few ever came near them, and the prince was continually begging his mother and the farmer to be allowed to go away and seek adventures and to make his own living. But she and the wise farmer always counselled him to wait, until, at last, when he was eighteen years of age, they had not the heart to forbid him any longer. So he started off one early morning, with a sword by his side, a big brass pot to hold water, a few pieces of silver , and a galail (1) or two-stringed bow in his hand, with which to shoot birds as he travelled.

Many a weary mile he tramped day after day, until, one morning, he saw before him just such a forest as that in which he had been born and bred, and he stepped joyfully into it, like one who goes to meet an old friend. Presently, as he made his way through a thicket, he saw a pigeon which he thought would make a good dinner, so he fired a pellet at it from his galail, but missed the pigeon which fluttered away with a startled clatter. At the same instant he heard a great clamour from beyond the thicket, and, on reaching the spot, he found an ugly old woman streaming wet and crying loudly as she lifted from her head an earthen vessel with a hole in it from which the water was pouring. When she saw the prince with his galail in his hand, she called out:

‘Oh, wretched one! why must you choose an old woman like me to play your pranks upon? Where am I to get a fresh pitcher instead of this one that you have broken with your foolish tricks? And how am I to go so far for water twice when one journey wearies me?’

But, mother,’ replied the prince, ‘I played no trick upon you! I did but shoot at a pigeon that should have served me for dinner, and as my pellet missed it, it must have broken your pitcher. But, in exchange, you shall have my brass pot, and that will not break easily; and as for getting water, tell me where to find it, and I’ll fetch it while you dry your garments in the sun, and carry it whither you will.’

At this the old woman’s face brightened. She showed him where to seek the water, and when he returned a few minutes later with his pot filled to the brim, she led the way without a word, and he followed. In a short while they came to a hut in the forest, and as they drew near it Ameer Ali beheld in the doorway the loveliest damsel his eyes had ever looked on. At the sight of a stranger she drew her veil about her and stepped into the hut, and much as he wished to see her again Ameer Ali could think of no excuse by which to bring her back, and so, with a heavy heart, he made his salutation, and bade the old woman farewell. But when he had gone a little way she called after him:

If ever you are in trouble or danger, come to where you now stand and cry: “Fairy of the Forest! Fairy of the forest, help me now!” And I will listen to you.’

The prince thanked her and continued his journey, but he thought little of the old woman’s saying, and much of the lovely damsel. Shortly afterwards he arrived at a city; and, as he was now in great straits, having come to the end of his money, he walked straight to the palace of the king and asked for employment. The king said he had plenty of servants and wanted no more; but the young man pleaded so hard that at last the rajah was sorry for him, and promised that he should enter his bodyguard on the condition that he would undertake any service which was especially difficult or dangerous. This was just what Ameer Ali wanted, and he agreed to do whatever the king might wish.

Soon after this, on a dark and stormy night, when the river roared beneath the palace walls, the sound of a woman weeping and wailing was heard above the storm. The king ordered a servant to go and see what was the matter; but the servant, falling on his knees in terror, begged that he might not be sent on such an errand, particularly on a night so wild, when evil spirits and witches were sure to be abroad. Indeed, so frightened was he, that the king, who was very kind-hearted, bade another to go in his stead, but each one showed the same strange fear. Then Ameer Ali stepped forward:

‘This is my duty, your majesty,’ he said, ‘I will go.’

The king nodded, and off he went. The night was as dark as pitch, and the wind blew furiously and drove the rain in sheets into his face; but he made his way down to the ford under the palace walls and stepped into the flooded water. Inch by inch, and foot by foot he fought his way across, now nearly swept off his feet by some sudden swirl or eddy, now narrowly escaping being caught in the branches of some floating tree that came tossing and swinging down the stream. At length he emerged, panting and dripping wet, on the other side. Close by the bank stood a gallows, and on the gallows hung the body of some evildoer, whilst from the foot of it came the sound of sobbing that the king had heard.

Ameer Ali was so grieved for the one who wept there that he thought nothing of the wildness of the night or of the roaring river. As for ghosts and witches, they had never troubled him, so he walked up towards the gallows where crouched the figure of the woman.

‘What ails you?’ he said.

Now the woman was not really a woman at all, but a horrid kind of witch who really lived in Witchland, and had no business on earth. If ever a man strayed into Witchland the ogresses used to eat him up, and this old witch thought she would like to catch a man for supper, and that is why she had been sobbing and crying in hopes that someone out of pity might come to her rescue.

So when Ameer Ali questioned her, she replied:

‘Ah, kind sir, it is my poor son who hangs upon that gallows; help me to get him down and I will bless you for ever.’

Ameer Ali thought that her voice sounded rather eager than sorrowful, and he suspected that she was not telling the truth, so he determined to be very cautious.

‘That will be rather difficult,’ he said, ‘for the gallows is high, and we have no ladder.’

‘Ah, but if you will just stoop down and let me climb upon your shoulders,’ answered the old witch, ‘I think I could reach him.’ And her voice now sounded so cruel that Ameer Ali was sure that she intended some evil. But he only said:

‘Very well, we will try.’ With that he drew his sword, pretending that he needed it to lean upon, and bent so that the old woman could clamber on to his back, which she did very nimbly. Then, suddenly, he felt a noose slipped over his neck, and the old witch sprang from his shoulders on to the gallows, crying:

‘Now, foolish one, I have got you, and will kill you for my supper.’

But Ameer Ali gave a sweep upwards with his sharp sword to cut the rope that she had slipped round his neck, and not only cut the cord but cut also the old woman’s foot as it dangled above him; and with a yell of pain and anger she vanished into the darkness.

Ameer Ali then sat down to collect himself a little, and felt upon the ground by his side an anklet that had evidently fallen off the old witch’s foot. This he put into his pocket, and as the storm had by this time passed over he made his way back to the palace. When he had finished his story, he took the anklet out of his pocket and handed it to the king, who, like everyone else, was amazed at the glory of the jewels which composed it. Indeed, Ameer Ali himself was astonished, for he had slipped the anklet into his pocket in the dark and had not looked at it since. The king was delighted at its beauty, and having praised and rewarded Ameer Ali, he gave the anklet to his daughter, a proud and spoiled princess.

Now in the women’s apartments in the palace there hung two cages, in one of which was a parrot and in the other a starling, and these two birds could talk as well as human beings. They were both pets of the princess who always fed them herself, and the next day, as she was walking grandly about with her treasure tied round her ankle, she heard the starling say to the parrot:

‘Oh, Toté’ (that was the parrot’s name), ‘how do you think the princess looks in her new jewel?’

‘Think?’ snapped the parrot, who was cross because they hadn’t given him his bath that morning, ‘I think she looks like a washerwoman’s daughter, with one shoe on and the other off! Why doesn’t she wear two of them, instead of going about with one leg adorned and the other empty?’

When the princess heard this she burst into tears; and sending for her father she declared that he must get her another such an anklet to wear on the other leg, or she would die of shame. So the king sent for Ameer Ali and told him that he must get a second anklet exactly like the first within a month, or he should be hanged, for the princess would certainly die of disappointment.

Poor Ameer Ali was greatly troubled at the king’s command, but he thought to himself that he had, at any rate, a month in which to lay his plans. He left the palace at once, and inquired of everyone where the finest jewels were to be got; but though he sought night and day he never found one to compare with the anklet. At last only a week remained, and he was in sore difficulty, when he remembered the Fairy of the forest, and determined to go without loss of time and seek her. Therefore away he went, and after a day’s travelling he reached the cottage in the forest, and, standing where he had stood when the old woman called to him, he cried:

‘Fairy of the forest! Fairy of the forest! Help me! help me!’

Then there appeared in the doorway the beautiful girl he had seen before, whom in all his wanderings he had never forgotten.

‘What is the matter?’ she asked, in a voice so soft that he listened like one struck dumb, and she had to repeat the question before he could answer. Then he told her his story, and she went within the cottage and came back with two wands, and a pot of boiling water. The two wands she planted in the ground about six feet apart, and then, turning to him, she said:

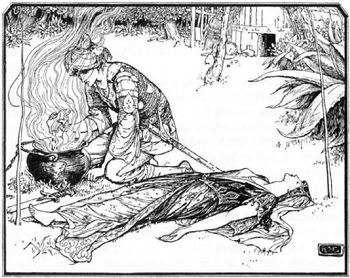

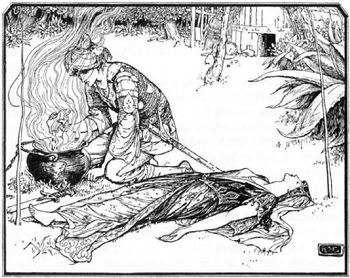

‘I am going to lie down between these two wands. You must then draw your sword and cut off my foot, and, as soon as you have done that, you must seize it and hold it over the cauldron, and every drop of blood that falls from it into the water will become a jewel. Next you must change the wands so that the one that stood at my head is at my feet, and the one at my feet stands at my head, and place the severed foot against the wound and it will heal, and I shall become quite well again as before.’

At first Ameer Ali declared that he would sooner be hanged twenty times over than treat her so roughly; but at length she persuaded him to do her bidding. He nearly fainted himself with horror when he found that, after the cruel blow which lopped her foot off, she lay as one lifeless; but he held the severed foot over the cauldron, and, as drops of blood fell from it, and he saw each turn in the water into shining gems, his heart took courage. Very soon there were plenty of jewels in the cauldron, and he quickly changed the wands, placed the severed foot against the wound, and immediately the two parts became one as before. Then the maiden opened her eyes, sprang to her feet, and drawing her veil about her, ran into the hut, and would not come out or speak to him any more. For a long while he waited, but, as she did not appear, he gathered up the precious stones and returned to the palace. He easily got some one to set the jewels, and found that there were enough to make, not only one, but three rare and beautiful anklets, and these he duly presented to the king on the very day that his month of grace was over.

The king embraced him warmly, and made him rich gifts; and the next day the vain princess put two anklets on each foot, and strutted up and down in them admiring herself in the mirrors that lined her room.

‘Oh, Toté,’ asked the starling, ‘how do you think our princess looks now in these fine jewels?’

‘Ugh!’ growled the parrot, who was really always cross in the mornings, and never recovered his temper until after lunch, ‘she’s got all her beauty at one end of her now; if she had a few of those fine gewgaws round her neck and wrists she would look better; but now, to my mind, she looks more than ever like the washerwoman’s daughter dressed up.’

Poor princess! she wept and stormed and raved until she made herself quite ill; and then she declared to her father that, unless she had bracelets and necklace to match the anklets she would die.

Again the king sent for Ameer Ali, and ordered him to get a necklace and bracelets to match those anklets within a month, or be put to a cruel death.

And again Ameer Ali spent nearly the whole month searching for the jewels, but all in vain. At length he made his way to the hut in the forest, and stood and cried:

‘Fairy of the forest! Fairy of the forest! Help me! help me!’

Once more the beautiful maiden appeared at his summons and asked what he wanted, and when he had told her she said he must do exactly as he had done the first time, except that now he must cut off both her hands and her head. Her words turned Ameer Ali pale with horror; but she reminded him that no harm had come to her before, and at last he consented to do as she bade him. From her severed hands and head there fell into the cauldron bracelets and chains of rubies and diamonds, emeralds and pearls that surpassed any that ever were seen. Then the head and hands were joined on to the body, and left neither sign nor scar. Full of gratitude, Ameer Ali tried to speak to her, but she ran into the house and would not come back, and he was forced to leave her and go away laden with the jewels.

When, on the day appointed, Ameer Ali produced a necklace and bracelets each more beautiful and priceless than the last, the king’s astonishment knew no bounds, and as for his daughter she was nearly mad with joy. The very next morning she put on all her finery, and thought that now, at least, that disagreeable parrot could find no fault with her appearance, and she listened eagerly when she heard the starling say:

‘Oh, Toté, how do you think our princess is looking now?’

‘Very fine, no doubt,’ grumbled the parrot; ‘but what is the use of dressing up like that for oneself only? She ought to have a husband -why doesn’t she marry the man who got her all these splendid things?’

Then the princess sent for her father and told him that she wished to marry Ameer Ali.

‘My dear child,’ said her father, ‘you really are very difficult to please, and want something new every day. It certainly is time you married someone, and if you choose this man, of course he shall marry you.’

So the king sent for Ameer Ali, and told him that within a month he proposed to do him the honour of marrying him to the princess, and making him heir to the throne.

On hearing this speech Ameer Ali bowed low and answered that he had done and would do the king all the service that lay in his power, save only this one thing. The king, who considered his daughter’s hand a prize for any man, flew into a passion, and the princess was more furious still. Ameer Ali was instantly thrown into the most dismal prison that they could find, and ordered to be kept there until the king had time to think in what way he should be put to death.

Meanwhile the king determined that the princess ought in any case to be married without delay, so he sent forth heralds throughout the neighbouring countries, proclaiming that on a certain day any person fitted for a bridegroom and heir to the throne should present himself at the palace.

When the day came, all the court were gathered together, and a great crowd assembled of men, young and old, who thought that they had as good a chance as anyone else to gain both the throne and the princess. As soon as the king was seated, he called upon an usher to summon the first claimant. But, just then, a farmer who stood in front of the crowd cried out that he had a petition to offer.

‘Well, hasten then,’ said the king; ‘I have no time to waste.’

‘Your majesty,’ said the farmer, ‘has now lived and administered justice long in this city, and will know that the tiger who is king of beasts hunts only in the forest, whilst jackals hunt in every place where there is something to be picked up.’

‘What is all this? what is all this?’ asked the king. ‘The man must be mad!’

‘No, your majesty,’ answered the farmer, ‘I would only remind your majesty that there are plenty of jackals gathered to-day to try and claim your daughter and kingdom: every city has sent them, and they wait hungry and eager; but do not, O king, mistake or pretend again to mistake the howl of a jackal for the hunting cry of a tiger.’

The king turned first red and then pale.

‘There is,’ continued the farmer, ‘a royal tiger bred in the forest who has the first and only true claim to your throne.’

‘Where? what do you mean?’ stammered the king, growing pale as he listened.

‘In prison,’ replied the farmer; ‘if your majesty will clear this court of the jackals I will explain.’

‘Clear the court!’ commanded the king; and, very unwillingly, the visitors left the palace.

‘Now tell me what riddle this is,’ said he.

Then the farmer told the king and his ministers how he had rescued the queen and brought up Ameer Ali; and he fetched the old queen herself, whom he had left outside. At the sight of her the king was filled with shame and self-reproach, and wished he could have lived his life over again, and not have married the mother of the proud princess, who caused him endless trouble until her death.

‘My day is past,’ said he. And he gave up his crown to his son Ameer Ali, who went once more and called to the forest fairy to provide him with a queen to share his throne.

‘There is only one person I will marry,’ said he. And this time the maiden did not run away, but agreed to be his wife. So the two were married without delay, and lived long and reigned happily.

As for the old woman whose pitcher Ameer Ali had broken, she was the forest maiden’s fairy godmother, and when she was no longer needed to look after the girl she gladly returned to fairyland.

The old king has never been heard to contradict his wife any more. If he even looks as if he does not agree with her, she smiles at him and says:

Is it the tiger, then? or the jackal?’ And he has not another word to say.

(1) A galail is a double-stringed bow from which bullets or pellets of hard dried clay can be fired with considerable force and precision

Nota originale.

Sciacallo o Tigre?

In una calda notte, nell’Hindostàn, un re e una regina giacevano svegli nel loro palazzo nel cuore della città. Di tanto in tanto un lieve soffio d’aria spirava attraverso la grata e loro speravano di potersi addormentare, ma non ci riuscivano mai. Ben presto furono più svegli che mai al suono di un ruggito fuori dal palazzo.

”Ascolta quella tigre!” osservò il re.

”La regina replicò: “Tigre? Come potrebbe esserci una tigre in città? È solo uno sciacallo.”

”Ti dico che era una tigre,” disse il re.

”E io ti dico che stai sognando se pensi che possa essere qualcos’altro che uno sciacallo,” rispose la regina.

”Io sostengo che era una tigre,” gridò il re; “non contraddirmi.”

”Sciocchezze!” sbottò la regina. “Era uno sciacallo.” E la disputa divenne così accesa che alla fine il re disse:

”Benissimo, chiameremo la guardia e glielo chiederemo; se era uno sciacallo, lascerò il regno e me ne andrò; e se era una tigre allora te ne andrai tu e io sposerò un’altra moglie.

La regina rispose: “Come ti piace, non c’è alcun dubbio su che cosa sia.”

Così il re chiamò due soldati che erano di guardia fuori e pose loro la questione. Ma, mentre la disputa continuava, il re e la regina si erano così agitati e parlavano a voce talmente alta che le guardie lì vicino avevano sentito tutto e una fece osservare all’altra:

”Stai attento a dichiarare che ha ragione il re, era certamente uno sciacallo, ma, se diciamo così, probabilmente il re non manterrà la sua parola di andarsene e ci troveremo nei guai, così sarà meglio per noi schierarci con lui.”

L’altra guardia fu d’accordo; perciò, quando il re chiese loro quale animale avessero udito, entrambe le guardie affermarono che era certamente una tigre e che aveva ragione il re, come sempre. Il re non fece commenti, ma mandò a chiamare un palanchino (1) e ordinò che vi fosse collocata la regina, comandando ai quattro portantini del palanchino di portarla lontano nella foresta e di lasciarvela. Nonostante le lacrime, fu obbliga a obbedire, e i portantini camminarono per tre giorni e tre notti finché giunsero in una fitta foresta. Posarono il palanchino con dentro la regina e tornarono di nuovo a casa.

Ora la regina pensava tra sé che il re non avesse voluto allontanarla per sempre e che ben presto, sbollita la collera, l’avrebbe fatta tornare indietro; così rimase tranquilla per un bel po’, ascoltando con tutta la propria attenzione per sentire rumore di passi che si avvicinavano, ma non sentiva niente. Dopo un po’ cominciò a innervosirsi, perché era sola, così sporse la testa dal palanchino e si guardò attorno. Era appena spuntato il giorno e gli insetti e gli uccelli stavano cominciando a muoversi; le foglie stormivano nella brezza calda; ma per quanto gli occhi della regina vagassero in ogni direzione, non c’era segno di presenza umana. Allora tutta la presenza di spirito l’abbandonò e cominciò a piangere.

Accadde che vicino alla radura in cui era stato lasciato il palanchino della regina, abitasse un uomo che aveva una piccola fattoria in mezzo alla foresta, dove lui e sua moglie vivevano da soli, lontani da qualsiasi confinante. Siccome faceva molto caldo il contadino stava dormendo sul tetto a terrazza della sua casa, ma fu svegliato dal suono di un pianto. Balzò in piedi e corse dabbasso più veloce che poté, verso il luogo della foresta dal quale proveniva il suono e lì trovò il palanchino.

”Oh, povera creatura che piangi,” gridò il contadino, fermandosi poco lontano, “chi sei?” A questo saluto da parte di uno sconosciuto la regina restò in silenzio, temendo il da farsi.

Il contadino ripeté: “Oh, tu che piangi, non aver paura di parlarmi, perché sei come una figlia per me. Dimmi, chi sei?”

La voce dell’uomo era tanto gentile che la regina si fece coraggio e parlò. E quando gli ebbe narrato la propria storia, il contadino chiamò la moglie, che la condusse in casa e le dette cibo da mangiare e un letto in cui giacere. Alcuni giorni più tardi, nella fattoria nacque un principino e, secondo il desiderio di sua madre, fu chiamato Ameer Ali.

Passarono gli anni senza alcun segno da parte del re. Sua moglie avrebbe potuto essere morta per quanto gliene importasse, tuttavia la regina viveva ancora con il contadino e il principino oramai era divenuto un giovanotto forte, bello e sano. Lì nella foresta sembravano lontani dal mondo; pochissimi li avvicinavano e il principe implorava continuamente sua madre e il contadino di permettergli di andarsene in cerca di avventure per farsi una vita. Ma sia che il saggio contadino gli consigliavano di aspettare finché, alla fine, quando ebbe diciotto anni, non ebbero cuore di proibirglielo ancora a lungo. Così partì una mattina presto, la spada al fianco, un grosso recipiente d’ottone per l’acqua, pochi pezzi d’argento e un arco a doppia corda in mano, con il quale colpire gli uccelli mentre era in viaggio.

Giorno dopo giorno percorse faticosamente miglia e miglia finché una mattina si trovò davanti una foresta come quella in cui era nato e cresciuto, e si arrestò pieno di gioia, come chi ritrovi un vecchio amico. Ben presto, mentre attraversava un boschetto, vide un piccione e pensò che sarebbe stato un’ottima cena, così scagliò un proiettile con il suo arco a doppia corda, ma mancò il piccione che volò via tubando spaventato. Nello stesso momento sentì un gran clamore provenire da oltre il boschetto, e, raggiungendo la radura, trovò un’orribili vecchia bagnata fradicia che piangeva a dirotto perché portava sulla testa un recipiente di terracotta con un buco dal quale scendeva l’acqua. Quando vide il principe con il doppio arco in mano, esclamò:

”Sventurato! Devi scegliere una vecchia come me per fare i tuoi scherzi? Dove troverò una brocca nuova al posto di questa che hai rotto con il tuo stupido giochetto? E come andrò lontanto a prendere l’acqua due volte quando già un solo viaggio mi stanca?”

Il principe rispose: “Madre, non ti ho giocato nessun tiro! Ho solo mirato a un piccione che mi sarebbe servito per la cena, e siccome il mio colpo ha fallito, deve aver rotto la tua brocca. In cambio ti darò il mio recipiente d’ottone, che non si romperà facilmente; e per quanto riguarda l’acqua, dimmi dove posso trovarla e andrò a prenderla mentre ti asciughi i vestiti al sole, e la porterò dove vorrai.

A queste parole il volto della vecchia si illuminò. Gli mostrò dove cercare l’acqua e quando dopo pochi minuti fu ritornato con il recipiente colmo fino all’orlo, gli fece strada senza una parola e lui la seguì. In breve giunsero a una capanna nella foresta e come si avvicinarono a essa Ameer Ali vide sulla soglia la più leggiadra fanciulla che i suoi occhi avessero mai ammirato. Alla vista dello straniero si avvolse nel velo e entrò nella capanna, e per quanto desiderasse vederla ancora, Amneer Ali pensava di non avere una scusa per farla tornare indietro e così, con il cuore pesante, salutò e disse addio alla vecchia. Ma aveva fatto solo un po’ di strada che lei gli gridò dietro:

”Se mai dovessi trovarti in difficoltà o in pericolo, torna dove sei ora e grida: ‘Fata della Foresta! Fata della Foresta, aiutami adesso!’ e io ti darò ascolto.”

Il principe la ringraziò e continuò il viaggio, ma pensava poco alle parole della vecchia e più alla bella fanciulla. Poco dopo arrivò in una città; e trovandosi in ristrettezze, aveva finito il denaro, andò al palazzo del re e chiese un lavoro. Il re rispose che aveva tanti servitori e non ne cercava altri; ma il giovane pregò così tanto che alla fine il rajah fu dispiaciuto per lui e promise che lo avrebbe fatto entrare nelle sue guardie del corpo a condizione che si impegnasse in qualunque impresa fosse particolarmente difficile o rischiosa. Era proprio ciò che Ameer Ali voleva e accettò di fare qualsiasi cosa il re desiderasse.

Poco dopo ciò, in una notte buia e tempestosa, in cui il fiume rumoreggiava sotto le mura del palazzo, oltre la tempesta si udì il suono di un pianto e di un lamento di donna. Il re ordinò a un servitore di andare a vedere che cosa succedesse; il servitore cadde in ginocchio terrorizzato, lo pregarono che non gli affidasse un simile incarico, specialmente in una notte così tempestosa, quando gli spiriti malvagi e le streghe di certo erano in giro. In verità, era così spaventato che il re, il quale era di animo gentile, ordinò a un altro di andare al suo posto, ma ognuno provava la medesima, strana paura. Allora Ameer Ali si fece avanti:

”È compito mio, vostra maestà,” disse, “andrò io.”

Il re annuì e lui andò. La notte era nera come il petrolio, il vento soffiava furiosamente e stendeva un velo di pioggia sul suo viso; ma lui seguì la propria strada giù fino al guado sotto le mura del palazzo e avanzò nell’acqua alta. A poco a poco, passo dopo passo, si fece strada, ora rovesciandosi per i gorghi e i mulinelli improvvisi, ora sfuggendo con difficoltà ai rami di alcuni alberi che galleggiavano e venivano sballottati e fatti girare dalla corrente. Infine approdò all’altra riva, ansante e fradicio. Vicino alla riva c’era un patibolo e dal patibolo pendeva il corpo di un malfattore, dalla cui base proveniva il suono di pianto che il re aveva udito

Ameer Ali era così triste per chi piangeva lì che non gli importava nulla della terribile notte o del fragore del fiume. Fantasmi e streghe non lo avevano mai turbato, così andò verso il patibolo sotto il quale era accovacciata una figura di donna.

”Che cosa ti affligge?” disse.

In realtà la donna non era del tutto una donna, ma on orribile razza di strega che viveva proprio nella Terra delle Streghe e non aveva niente che fare con il mondo reale. Se mai un uomo si smarriva nella Terra delle Streghe, le orchesse erano solite mangiarlo, e questa vecchia strega pensava che le sarebbe piaciuto acciuffare un uomo per cena, per questo stava singhiozzando e piangendo, nella speranza che qualcuno s’impietosisse e potesse venire in suo soccorso.

Così quando Ameer Ali le rivolse la domanda, rispose:

”Ah, gentile signore, è il mio povero figlio colui che pende dal patibolo; aiutami a tirarlo giù e ti benedirò per sempre.”

Ameer Ali pensò che quella voce suonasse più avida che afflitta, e sospettò che la donna non stesse dicendo la verità, così decise di essere molto cauto.

”È piuttosto difficile,” disse, “perché il patibolo è alto e non abbiamo una scala.”

La vecchia strega rispose: ”Ah, se solo volessi piegarti e lasciarmi salire sulle tue spalle, penso che potrei raggiungerlo.” E la sua voce ora suonava così crudele che Ameer Ali fu certo avesse intenzioni malvagie. Tuttavia disse solo:

”Benissimo, ci proveremo.” E con ciò estrasse la spada, fingendo gli servisse per piegarsi, e si curvò affinché la vecchia potesse salire sul suo dorso, cosa che fece assai agilmente. Allora, improvvisamente, sentì un cappio scivolargli al collo e la vecchia strega balzò dalla sua schiena sul patibolo, gridando:

”E adesso, sciocco, ti ho preso e ti ucciderò per la mia cena.”

Ma Ameer Ali diede un colpo all’insù con la spada affilata per tagliare la corda che la vecchia gli aveva messo intorno al collo, e non solo tagliò la corda, ma anche il piede della vecchia che ciondolava sopra di lui; e lei svanì nelle tenebre con un urlo di dolore e di collera.

Ameer Ali allora sedette per riprendersi un po’e sentì sul terreno al proprio fianco una cavigliera, che evidentemente era caduta dal piede della vecchia strega. La mise nella borsa e appena la tempesta si fu placata, riprese la via del ritorno verso il palazzo. Quando ebbe finito la storia, prese la cavigliera dalla borsa e la porse al re il quale, come chiunque, fu stupito dalla magnificenza dei gioielli di cui era fatta. In effetti lo stesso Ameer Ali ne era meravigliato perché aveva fatto scivolare la cavigliera nella borsa al buio e non l’aveva guardata da allora. Il re fu lietissimo della sua bellezza, e dopo ave lodato e ricompensato Ameer Ali, diede la cavigliera in dono alla figlia, una principessa superba e viziata.

Negli appartamenti femminili del palazzo si trovavano due gabbie, in una c’era un pappagallo e nell’altra uno storno, e questi due uccelli parlavano bene quasi come esseri umani. Entrambi erano gli animali preferiti della principessa, che li nutriva sempre personalmente, e il giorno seguente, mentre stava camminando superbamente con il gioiello alla caviglia, sentì lo storno dire al pappagallo:

”Oh, Toté (era questo il nome del pappagallo), come pensi che sembri la principessa con il suo nuovo gioiello?”

”Che cosa penso?” disse aspramente il pappagallo, che era contrariato perché quella mattina non aveva fatto il bagno, “Penso che sembri la figlia di una lavandaia con una scarpa sì e una no! Perché non le indossa tutte e due, invece di andare in giro con una gamba adorna e una nuda?”

Quando la principessa udì queste parole, scoppiò in lacrime; e fatto chiamare suo padre, dichiarò che doveva avere anche l’altra cavigliera da indossare sull’altra gamba, o sarebbe morta di vergogna. Così il re mandò a chiamare Ameer Ali e gli disse che entro un mese doveva trovare una seconda cavigliera esattamente come la prima, o sarebbe stato impiccato, perché la principessa sarebbe certo morta di delusione.

Il povero Ameer Ali fu assai turbato dall’ordine del re, ma pensò che dopotutto aveva un mese in cui architettare piani. Lasciò subito il palazzo e chiese a tutti dove si trovassero i più bei gioielli, ma per quanto cercasse giorno e notte, non ne trovò uno paragonabile alla cavigliera. Alla fine era rimasta solo una settimana e lui era in grande difficoltà, quando si rammentò della Fata della foresta e decise di andare a cercarla senza perder tempo. Perciò andò via, e dopo un giorno di viaggio raggiunse la casetta nella foresta e, stando dove si trovava quando la vecchia lo aveva chiamato, gridò:

”Fata della foresta! Fata della foresta! Aiutami! Aiutami!”

Allora comparve sulla soglia la splendida fanciulla che aveva visto in precedenza, che non aveva mai dimenticato per in tutto il suo girovagare.

”Che succede?” chiese lei con una voce così dolce da lasciarlo ammutolito, e dovette ripetere la domanda perché le rispondesse. Allora lui le narrò la propria storia, lei entrò nella casetta e ne uscì con due bastoncini e una pentola d’acqua bollente. Piantò i due bastoncini per terra alla distanza di sei piedi (2) e poi, volgendfosi verso di lui, disse:

Sto per schiacciare un pisolino tra questi due bastoncini. Tu devi estrarre la spada e tagliarmi il piede e, appena lo avrai fatto, dovrai prenderlo e tenerlo sulla pentola, e ogni goccia di sangue che cadrà nell’acqua diventerà un gioiello. Poi dovrai scambiare i bastoncini in modo che quello che sta vicino alla testa sia infondo ai piedi, e quello in fondo ai piedi sia vicino alla testa, e mettere il piede mozzato contro la ferita ed essa guarirà, così io tornerò completamente sana come prima.”

Dapprima Ameer Ali dichiarò che si sarebbe fatto impiccare venti volte piuttosto di trattarla tanto duramente; ma alla fine lei lo persuase a eseguire l’ordine. Lui per poco non svenne dall’orrore quando scoprì che, dopo il taglio crudele con cui le aveva mozzato il piede, lei giaceva come morta; ma resse il piede reciso sulla pentola e, come le gocce di sangue ne caddero e vide ognuna muttarsi nell’acqua in gemme scintillanti, ritrovò il coraggio. Assai presto la pentola fu piena di gioielli e lui rapidamente cambiò di posto ai bastoncini, appoggià il piede mozzato contro la ferita e immediatamente le due parti una come prima. Allaora la ragazza aprì gli occhi, si alzò in piedi e, avvolgendosi nel velo, corse in casa e non gli parlò ne si mostrò più. Per un po’ attese ma, siccome lei non appariva, raccolse le pietre preziose e ritorno al palazzo. Trovò facilmente qualcuno che realizzasse gioelli e scoprì che c’erano abbastanza pietre per fare non solo una, ma tre straordinarie e stupende cavigliere, e tante ne presentò al re proprio il giorno in cui scadeva il mese di tempo.

Il re lo abbracciò calorosamente e gli fece ricchi doni; e il giorno seguente la principessa vanitosa portava due cavigliere a ciascun piede, e camminava impettita su e giù ammirandosi negli specchi che erano allineati nella sua stanza.

Lo storno chiese: ”Oh, Toté, che cosa pensi che sembri la nostra principessa con quei bei gioielli?”

”Ugh!” borbottò il pappagallo, che era sempre assai contrariato la mattina e il cui umore migliorava solo dopo pranzo, “Ora tutta la sua bellezza sta alla sua estremità; se avesse un po’ di quei gingilli al collo e ai polsi, sarebbe meglio; per ora sembra più che mai la figlia di una lavandaia vestita a festa.”

Povera principessa! Pianse e diede in escandescenze e farneticò finché si ammalò; e allora annunciò a suo padre che sarebbe morta se non avesse avuto bracciatetti e collane da abbinare alle cavigliere.

Il re mandò di nuovo a chiamare Ameer Ali e gli ordinò di procurare entro un mese una collana e dei braccialetti che si accompagnassero alle cavigliere, altrimenti sarebbe andato incontro a una morte crudele.

E di nuovo Ameer Ali impiegò l’intero mese cercando i gioielli, ma invano. Alla fine riprese la via della casetta nella foresta, si fermò e gridò:

”Fata della foresta! Fata della foresta! Aiutami! Aiutami!”

Ancora una volta la bella fanciulla apparve alla sua invocazione e gli chiese che cosa volesse, e quando glielo ebbe detto lei disse che dove fare esattamente come la prima volta, tranne che ora doveva tagliarle le mani e la testa. Le sue parole fecero impallidire di orrore Ameer Ali; ma lei gli rammentò che nessun danno le sarebbe venuto e alla fine lui acconsentì a fare ciò che gli aveva ordinato. Dalle mani e dalla testa mozzate caddero nella pentola braccialetti e catene di rubini e di diamanti, di smeraldi e di perle che superarono qualsiasi altra cosa mai vista. Poi la testa e le mani furono riunite al corpo e lei se ne andò senza sego o ferita. Pieno di gratitudine, Ameer Ali cercò di parlarle, ma lei corse in casa e non ne uscì, così lui fu obbligato a lasciarla e d andare via carico di gioielli.

Quando il giorno stabilito Ameer Ali mostrò una collana e dei braccialetti gli uni più belli e preziosi dell’altra, lo stupore del re non conobbe limiti e sua figlia quasi impazzì di gioia. Il mattino seguente indossò tutti quegli ornamenti vistosi e penso che adesso, dopotutto, quell’antipatico pappagallo non avrebbe potuto trovare difetti nel suo aspetto, e ascoltò con impazienza quando lo storno disse:

”Oh, Toté, che cosa pensi che sembri ora la nostra principessa?”

”Molto bella, senza dubbio,” borbottò il pappagallo; “ma a che serve abbigliarsi così solo per se stessi? Dovrebbe avere un marito – perché non sposa l’uomo che le ha dato tutte queste splendide cose?”

Allora la principessa mandò a chiamare suo padre e gli disse che desiderava sposare Ameer Ali.

Il padre disse: “Mia cara figlia, tu sei davvero molto difficile da accontentare, e ogni giorno vuoi qualcosa di nuovo. È certamente tempo che tu sposi qualcuno e se tu hai scelto quest’uomo, naturalmente lui ti sposerà.”

Così il re mandò a chiamare Ameer Ali e gli disse che entro un mese si proponeva di fargli l’onore di sposare la principessa e di farlo suo erede al trono.

Sentendo queste parole Ameer Ali fece un profondo inchino e rispose che avrebbe reso al re tutti i servigi che erano in suo potere, tranne quello. Il re, che considerava la mano di sua figlia come un premio per qualsiasi uomo, s’infiammò d’ira e la principessa s’infuriò anche di più. Ameer Ali fu gettato all’istante nella più lugubre prigione che ci fosse, e fu ordinato che lì restasse finché non avesse avuto tempo di pensare in quale modo potergli dare la morte.

Nel frattempo il re aveva deciso che la principessa dovesse sposarsi in ogni caso senza indugio, così mandò araldi nei paesi vicini, proclamando che un certo giorno si presentasse a palazzo ogni persona adatta ad essere promesso sposo ed erede al trono.

Quando venne il giorno stabilito, fu chiamata a raccolta tutta la corte e una folla di uomini, giovani e vecchi, che ritenevano ciascuno di avere buone possibilità di ottenere sia il trono sia la principessa. Appena il re si fu seduto, chiamò il maestro delle cerimonie perché convocasse il primo pretendente. Ma, proprio in quel momento, un contadino che stava davanti alla folla gridò che aveva una supplica da presentare.

”Bene, allora sbrigati,” disse il re, “non ho tempo da perdere.”

Il contadino disse: “Vostra maestà è vissuto e ha amministrato la giustizia a lungo in questa città, e saprà che la tigre, che è il re degli animali, caccia solo nella foresta, mentre lo sciacallo caccia in ogni luogo in cui ci sia qualcosa da prendere.”

”Che significa tutto ciò? Che significa tutto ciò?” chiese il re. “Quell’uomo deve essere pazzo!”

Il contadino rispose: “No, vostra maestà. Vorrei solo ricordarvi che qui è pieno di sciacalli che provano a reclamare vostra figlia e il vostro regno; ogni città ne ha mandati, e aspettano famelici e avidi; ma non scambiate, o fingete di scambiare, l’ululato dello sciacallo per il ruggito di caccia di una tigre.”

Il re dapprima arrossì e poi impallidì.

Il contadino continuò: “C’è una tigre reale allevata nella foresta che è l’unico e il vero pretendente al trono.”

”Dove? Che cosa vuoi dire?” balbettò il re, impallidendo nel sentire.

Il contadino rispose: “In prigione, se vostra maestà sgombrerà la corte dagli sciacalli, io spiegherò.”

”Sgomberate la corte!” ordinò il re; e, assai malvolentieri, gli ospiti abbandonarono il palazzo.

”Adesso sciogli l’enigma.” disse il re.

Allora il contadino narrò al re e ai suoi ministri come avesse soccorso la regina e allevato Ameer Ali; e andò a prendere l’anziana regina che aveva lasciato fuori. Alla sua vista il re fu colmo di vergogna e di rimorso, e desiderò poter vivere di nuovo la sua vita e non aver sposato la madre della superba principessa che gli avrebbe causato continue preoccupazioni finché non fosse morta.

”Il mio tempo è trascorso.” Disse. E diede la corona a suo figlio Ameer Ali, che andò a chiamare ancora una volta la fata della foresta che gli procurasse una regina con la quale dividere il trono.

”È solo una la persona che sposerò,” disse. E stavolta la fanciulla non corse via, ma accettò di diventare sua moglie. Così i due furono uniti in matrimonio senza indugio, e vissero a lungo, regnando felicemente.

Per quanto riguarda la vecchia a cui Ameer Ali aveva rotto la brocca, era la fata madrina della fanciulla della foresta, e poiché non doveva più occuparsi della fanciulla, tornò volentieri nella terra delle fate.

Il vecchio re non fu mai più sentito contraddire sua moglie. Se a volte capita che non sia d’accordo con lei, gli sorride e dice:

”Allora, è la tigre o lo sciacallo?” e lui non ha altro da dire.

(1) Portantina usata in Oriente, specialmente nel passato, per il trasporto di persone di alto rango.

(2) unità di lunghezza pari a 30.48 cm

Origine sconosciuta, senza bibliografia

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)