He wins who waits

(MP3

-20'36'')

Once upon a time there reigned a king who had an only daughter. The girl had been spoiled by everybody from her birth, and, besides being beautiful, was clever and wilful, and when she grew old enough to be married she refused to have anything to say to the prince whom her father favoured, but declared she would choose a husband for herself. By long experience the king knew that when once she had made up her mind, there was no use expecting her to change it, so he inquired meekly what she wished him to do.

‘Summon all the young men in the kingdom to appear before me a month from to-day,’ answered the princess; ‘and the one to whom I shall give this golden apple shall be my husband.’

‘But, my dear—’ began the king, in tones of dismay.

‘The one to whom I shall give this golden apple shall be my husband,’ repeated the princess, in a louder voice than before. And the king understood the signal, and with a sigh proceeded to do her bidding.

The young men arrived—tall and short, dark and fair, rich and poor. They stood in rows in the great courtyard in front of the palace, and the princess, clad in robes of green, with a golden veil flowing behind her, passed before them all, holding the apple. Once or twice she stopped and hesitated, but in the end she always passed on, till she came to a youth near the end of the last row. There was nothing specially remarkable about him, the bystanders thought; nothing that was likely to take a girl’s fancy. A hundred others were handsomer, and all wore finer clothes; but he met the princess’s eyes frankly and with a smile, and she smiled too, and held out the apple.

‘There is some mistake,’ cried the king, who had anxiously watched her progress, and hoped that none of the candidates would please her. ‘It is impossible that she can wish to marry the son of a poor widow, who has not a farthing in the world! Tell her that I will not hear of it, and that she must go through the rows again and fix upon someone else’; and the princess went through the rows a second and a third time, and on each occasion she gave the apple to the widow’s son. ‘Well, marry him if you will,’ exclaimed the angry king; ‘but at least you shall not stay here.’ And the princess answered nothing, but threw up her head, and taking the widow’s son by the hand, they left the castle.

That evening they were married, and after the ceremony went back to the house of the bridegroom’s mother, which, in the eyes of the princess, did not look much bigger than a hen-coop.

The old woman was not at all pleased when her son entered bringing his bride with him.

‘As if we were not poor enough before,’ grumbled she. ‘I dare say this is some fine lady who can do nothing to earn her living.’ But the princess stroked her arm, and said softly:

‘Do not be vexed, dear mother; I am a famous spinner, and can sit at my wheel all day without breaking a thread.’

And she kept her word; but in spite of the efforts of all three, they became poorer and poorer; and at the end of six months it was agreed that the husband should go to the neighbouring town to get work. Here he met a merchant who was about to start on a long journey with a train of camels laden with goods of all sorts, and needed a man to help him. The widow’s son begged that he would take him as a servant, and to this the merchant assented, giving him his whole year’s salary beforehand. The young man returned home with the news, and next day bade farewell to his mother and his wife, who were very sad at parting from him.

‘Do not forget me while you are absent,’ whispered the princess as she flung her arms round his neck; ‘and as you pass by the well which lies near the city gate, stop and greet the old man you will find sitting there. Kiss his hand, and then ask him what counsel he can give you for your journey.’

Then the youth set out, and when he reached the well where the old man was sitting he asked the questions as his wife had bidden him.

‘My son,’ replied the old man, ‘you have done well to come to me, and in return remember three things: “She whom the heart loves, is ever the most beautiful.” “Patience is the first step on the road to happiness.” “He wins who waits.”’

The young man thanked him and went on his way. Next morning early the caravan set out, and before sunset it had arrived at the first halting place, round some wells, where another company of merchants had already encamped. But no rain had fallen for a long while in that rocky country, and both men and beasts were parched with thirst. To be sure, there was another well about half a mile away, where there was always water; but to get it you had to be lowered deep down, and, besides, no one who had ever descended that well had been known to come back.

However, till they could store some water in their bags of goat-skin, the caravans dared not go further into the desert, and on the night of the arrival of the widow’s son and his master, the merchants had decided to offer a large reward to anyone who was brave enough to go down into the enchanted well and bring some up. Thus it happened that at sunrise the young man was aroused from his sleep by a herald making his round of the camp, proclaiming that every merchant present would give a thousand piastres to the man who would risk his life to bring water for themselves and their camels.

The youth hesitated for a little while when he heard the proclamation. The story of the well had spread far and wide, and long ago had reached his ears. The danger was great, he knew; but then, if he came back alive, he would be the possessor of eighty thousand piastres. He turned to the herald who was passing the tent:

‘I will go,’ said he.

‘What madness!’ cried his master, who happened to be standing near. ‘You are too young to throw away your life like that. Run after the herald and tell him you take back your offer.’ But the young man shook his head, and the merchant saw that it was useless to try and persuade him.

‘Well, it is your own affair,’ he observed at last. ‘If you must go, you must. Only, if you ever return, I will give you a camel’s load of goods and my best mule besides.’ And touching his turban in token of farewell, he entered the tent.

Hardly had he done so than a crowd of men were seen pouring out of the camp.

‘How can we thank you!’ they exclaimed, pressing round the youth. ‘Our camels as well as ourselves are almost dead of thirst. See! here is the rope we have brought to let you down.’

‘Come, then,’ answered the youth. And they all set out.

On reaching the well, the rope was knotted securely under his arms, a big goat-skin bottle was given him, and he was gently lowered to the bottom of the pit. Here a clear stream was bubbling over the rocks, and, stooping down, he was about to drink, when a huge Arab appeared before him, saying in a loud voice:

‘Come with me!’

The young man rose, never doubting that his last hour had come; but as he could do nothing, he followed the Arab into a brilliantly lighted hall, on the further side of the little river. There his guide sat down, and drawing towards him two boys, one black and the other white, he said to the stranger:

‘I have a question to ask you. If you answer it right, your life shall be spared. If not, your head will be forfeit, as the head of many another has been before you. Tell me: which of my two children do I think the handsomer.’

The question did not seem a hard one, for while the white boy was as beautiful a child as ever was seen, his brother was ugly even for a negro. But, just as the youth was going to speak, the old man’s counsel flashed into the youth’s mind, and he replied hastily: ‘The one whom we love best is always the handsomest.’

‘You have saved me!’ cried the Arab, rising quickly from his seat, and pressing the young man in his arms. ‘Ah! if you could only guess what I have suffered from the stupidity of all the people to whom I have put that question, and I was condemned by a wicked genius to remain here until it was answered! But what brought you to this place, and how can I reward you for what you have done for me?’

‘By helping me to draw enough water for my caravan of eighty merchants and their camels, who are dying for want of it,’ replied the youth.

‘That is easily done,’ said the Arab. ‘Take these three apples, and when you have filled your skin, and are ready to be drawn up, lay one of them on the ground. Half-way to the earth, let fall another, and at the top, drop the third. If you follow my directions no harm will happen to you. And take, besides, these three pomegranates, green, red and white. One day you will find a use for them!’

The young man did as he was told, and stepped out on the rocky waste, where the merchants were anxiously awaiting him. Oh, how thirsty they all were! But even after the camels had drunk, the skin seemed as full as ever.

Full of gratitude for their deliverance, the merchants pressed the money into his hands, while his own master bade him choose what goods he liked, and a mule to carry them.

So the widow’s son was rich at last, and when the merchant had sold his merchandise, and returned home to his native city, his servant hired a man by whom he sent the money and the mule back to his wife.

‘I will send the pomegranates also,’ thought he ‘for if I leave them in my turban they may some day fall out,’ and he drew them out of his turban. But the fruit had vanished, and in their places were three precious stones, green, white and red.

For a long time he remained with the merchant, who gradually trusted him with all his business, and gave him a large share of the money he made. When his master died, the young man wished to return home, but the widow begged him to stay and help her; and one day he awoke with a start, to remember that twenty years had passed since he had gone away.

‘I want to see my wife,’ he said next morning to his mistress. ‘If at any time I can be of use to you, send a messenger to me; meanwhile, I have told Hassan what to do.’ And mounting a camel he set out.

Now, soon after he had taken service with the merchant a little boy had been born to him, and both the princess and the old woman toiled hard all day to get the baby food and clothing. When the money and the pomegranates arrived there was no need for them to work any more, and the princess saw at once that they were not fruit at all, but precious stones of great value. The old woman, however, not being accustomed, like her daughter-in-law, to the sight of jewels, took them only for common fruit, and wished to give them to the child to eat. She was very angry when the princess hastily took them from her and hid them in her dress, while she went to the market and bought the three finest pomegranates she could find, which she handed the old woman for the little boy.

Then she bought beautiful new clothes for all of them, and when they were dressed they looked as fine as could be. Next, she took out one of the precious stones which her husband had sent her, and placed it in a small silver box. This she wrapped up in a handkerchief embroidered in gold, and filled the old woman’s pockets with gold and silver pieces.

‘Go, dear mother,’ she said, ‘to the palace, and present the jewel to the king, and if he asks you what he can give you in return, tell him that you want a paper, with his seal attached, proclaiming that no one is to meddle with anything you may choose to do. Before you leave the palace distribute the money amongst the servants.’

The old woman took the box and started for the palace. No one there had ever seen a ruby of such beauty, and the most famous jeweller in the town was summoned to declare its value. But all he could say was:

‘If a boy threw a stone into the air with all his might, and you could pile up gold as high as the flight of the stone, it would not be sufficient to pay for this ruby.’

At these words the king’s face fell. Having once seen the ruby he could not bear to part with it, yet all the money in his treasury would not be enough to buy it. So for a little while he remained silent, wondering what offer he could make the old woman, and at last he said:

‘If I cannot give you its worth in money, is there anything you will take in exchange?’

‘A paper signed by your hand, and sealed with your seal, proclaiming that I may do what I will, without let or hindrance,’ answered she promptly. And the king, delighted to have obtained what he coveted at so small a cost, gave her the paper without delay. Then the old woman took her leave and returned home.

The fame of this wonderful ruby soon spread far and wide, and envoys arrived at the little house to know if there were more stones to sell. Each king was so anxious to gain possession of the treasure that he bade his messenger outbid all the rest, and so the princess sold the two remaining stones for a sum of money so large that if the gold pieces had been spread out they would have reached from here to the moon. The first thing she did was to build a palace by the side of the cottage, and it was raised on pillars of gold, in which were set great diamonds, which blazed night and day. Of course the news of this palace was the first thing that reached the king her father, on his return from the wars, and he hurried to see it. In the doorway stood a young man of twenty, who was his grandson, though neither of them knew it, and so pleased was the king with the appearance of the youth, that he carried him back to his own palace, and made him commander of the whole army.

Not long after this, the widow’s son returned to his native land. There, sure enough, was the tiny cottage where he had lived with his mother, but the gorgeous building beside it was quite new to him. What had become of his wife and his mother, and who could be dwelling in that other wonderful place? These were the first thoughts that flashed through his mind; but not wishing to betray himself by asking questions of passing strangers, he climbed up into a tree that stood opposite the palace and watched.

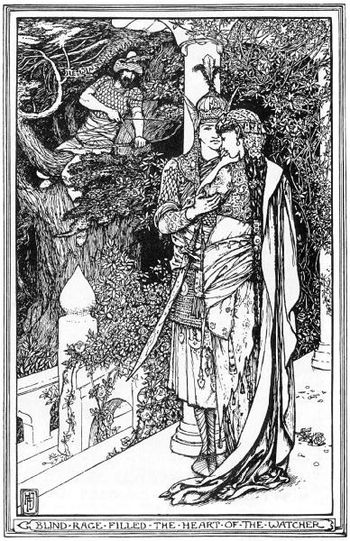

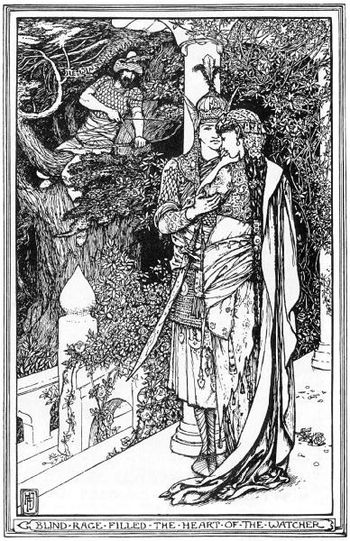

By-and-by a lady came out, and began to gather some of the roses and jessamine that hung about the porch. The twenty years that had passed since he had last beheld her vanished in an instant, and he knew her to be his own wife, looking almost as young and beautiful as on the day of their parting. He was about to jump down from the tree and hasten to her side, when she was joined by a young man who placed his arm affectionately round her neck. At this sight the angry husband drew his bow, but before he could let fly the arrow, the counsel of the wise man came back to him: ‘Patience is the first step on the road to happiness.’ And he laid it down again.

At this moment the princess turned, and drawing her companion’s head down to hers, kissed him on each cheek. A second time blind rage filled the heart of the watcher, and he snatched up his bow from the branch where it hung, when words, heard long since, seemed to sound in his ears:

‘He wins who waits.’ And the bow dropped to his side. Then, through the silent air came the sound of the youth’s voice:

‘Mother, can you tell me nothing about my father? Does he still live, and will he never return to us?’

‘Alas! my son, how can I answer you?’ replied the lady. ‘Twenty years have passed since he left us to make his fortune, and, in that time, only once have I heard aught of him. But what has brought him to your mind just now?’

‘Because last night I dreamed that he was here,’ said the youth, ‘and then I remembered what I have so long forgotten, that I had father, though even his very history was strange to me. And now, tell me, I pray you, all you can concerning him.’

And standing under the jessamine, the son learnt his father’s history, and the man in the tree listened also.

‘Oh,’ exclaimed the youth, when it was ended, while he twisted his hands in pain, ‘I am general-in-chief, you are the king’s daughter, and we have the most splendid palace in the whole world, yet my father lives we know not where, and for all we can guess, may be poor and miserable. To-morrow I will ask the king to give me soldiers, and I will seek him over the whole earth till I find him.’

Then the man came down from the tree, and clasped his wife and son in his arms. All that night they talked, and when the sun rose it still found them talking. But as soon as it was proper, he went up to the palace to pay his homage to the king, and to inform him of all that had happened and who they all really were. The king was overjoyed to think that his daughter, whom he had long since forgiven and sorely missed, was living at his gates, and was, besides, the mother of the youth who was so dear to him. ‘It was written beforehand,’ cried the monarch. ‘You are my son-in-law before the world, and shall be king after me.’

And the man bowed his head.

He had waited; and he had won.

From Contes Arméniens. Par Frédéric Macler.)

Vince chi aspetta

C’era una volta un re che aveva un’unica figlia. La fanciulla era stata viziata da tutti sin dalla nascita e, oltre ad essere diventata bellissima, era intelligente e testarda e quando fu diventata abbastanza grande per sposarsi, rifiutò di aver a che fare con il principe che suo padre caldeggiava e dichiarò che si sarebbe scelta un marito da sola. Per lunga esperienza il re sapeva che, quando lei si metteva in testa una cosa, non c’era modo di farle cambiare idea così chiese con mitezza che cosa desiderava che lui facesse.

“Convoca al mio cospetto tutti i giovani del regno tra un mese da oggi,” rispose la principessa, “e colui al quale darò questa mela d’oro sarà mio marito.”

“Ma, mia cara...” cominciò il re, costernato.

“Quello a cui darò questa mela d’oro sarà mio marito.” ripeté la principessa, a voce più alta di prima. E il re capì l’antifona e con un sospiro cominciò a fare ciò che lei aveva ordinato.

I giovani arrivarono… alti e bassi, bruni e biondi, ricchi e poveri. Formarono file nel grande cortile di fronte al palazzo e la principessa, vestita di verde con un velo dorato che le ricadeva morbidamente dietro, passò davanti a tutti loro, reggendo la mela. Una o due volte si fermò ed esitò, ma alla fine passò sempre oltre finché giunse a un ragazzo vicino al termine dell’ultima fila. Non vi era nulla di particolarmente notevole in lui, pensarono gli astanti; niente che potesse facilmente colpire la fantasia di una fanciulla. Un centinaio d’altri erano più attraenti e tutti indossavano gli abiti più belli, ma lui incontrò con franchezza lo sguardo della principessa e le sorrise, sorrise anche lei e gli porse la mela.

“Ci deve essere un equivoco,” strillò il re, che aveva assistito con ansia agli sviluppi della faccenda e aveva sperato che nessuno dei candidati le piacesse. “È impossibile che possa desiderare di sposare il figlio di una povera vedova che non ha un soldo! Ditele che non se ne parla e che deve percorrere di nuovo le file e scegliere qualcun altro.” e la principessa passò tra le file una seconda e una terza volta e in ciascuna occasione dette la mela al figlio della vedova. “Ebbene, sposalo, se vuoi,” esclamò incollerito il re, “ma almeno non starai qui.” e la principessa non rispose nulla, sollevò la testa, prese per mano il figlio della vedova e lasciarono il castello.

Si sposarono quella sera e dopo la cerimonia tornarono a casa della madre dello sposo, che agli occhi della principessa non sembrava più grande di un pollaio.

La vecchia non fu proprio contenta quando il figlio entrò conducendo con sé la sposa.

“Come se non fossimo già stati abbastanza poveri prima.” brontolò. “Suppongo che questa sia una di quelle belle dame che non fanno nulla per guadagnarsi da vivere.” La principessa le accarezzo un braccio e disse dolcemente:

“Non preoccuparti, madre cara; sono una famosa filatrice e posso sedere al mio filatoio tutto il giorno senza rompere un filo.”

E mantenne la parola, ma nonostante gli sforzi di tutti e tre, diventavano sempre più poveri e dopo sei mesi convennero che il marito sarebbe andato nella città vicina a cercare lavoro. Lì incontrò un mercante che stava per intraprendere un lungo viaggio con una carovana di cammelli carichi di ogni sorta di merci e aveva bisogno di un uomo che lo aiutasse. Il figlio della vedova lo pregò di prenderlo come servitore e il mercante acconsentì, dandogli in anticipo un intero anno di salario. Il ragazzo tornò a casa con le notizie e il giorno seguente disse addio alla madre e alla moglie, che erano molto tristi separandosi da lui.

“Non dimenticarmi mentre sei lontano,” sussurrò la principessa mentre gli gettava le braccia al collo, “e siccome passerai dal pozzo che si trova vicino alla porta della città, fermati a salutare il vecchio che troverai seduto lì. Baciagli la mano e poi chiedigli che consiglio ti possa dare per il viaggio.”

poi il ragazzo se ne andò e quando raggiunse il pozzo presso il quale era seduto il vecchio, gli rivolse domande come aveva detto sua moglie.

“Figlio mio,” rispose il vecchio, “hai fatto bene a venire da me e in cambio rammenta queste tre cose: ‘Colei che il cuore ama, è sempre la più bella’, ‘La pazienza è il primo passo sulla strada della felicità’, ‘Vince chi aspetta’.”

Il ragazzo lo ringraziò e riprese la strada. Il mattino seguente assai presto la carovana ripartì e prima del tramonto era giunta al primo luogo di sosta, circondato da alcuni pozzo, in cui si era già accampata un’altra compagnia di mercanti. Però da lungo tempo non era caduta pioggia in quel paese roccioso e sia gli uomini che gli animali erano assetati. In effetti c’era un altro pozzo a circa mezzo miglio in cui si trovava sempre acqua, ma per attingerla bisognava calarsi in profondità e, inoltre, nessuno di quelli che erano scesi in quel pozzo aveva mai saputo come tornare su.

In ogni modo finché avessero potuto far provvista d’acqua negli otri di pelle di pecora, le carovane non temevano di addentrarsi nel deserto e la notte dell’arrivo del figlio della vedova e del suo padrone i mercanti avevano deciso di offrire una generosa ricompensa a chiunque fosse abbastanza audace da scendere nel pozzo incantato e riportare l’acqua. Di conseguenza avvenne che al tramonto il ragazzo fosse destato dal sonno da un araldo il quale che girava per l’accampamento annunciando che ciascun mercante avrebbe dato mille piastre all’uomo che avesse rischiato la vita per portare acqua a loro e ai cammelli.

Il ragazzo esitò un poco mentre ascoltava l’annuncio. La storia del pozzo si era diffusa in lungo e in largo e da tanto tempo gli era nota. Il pericolo era grande, lo sapeva, tuttavia, se fosse tornato indietro viso, sarebbe entrato in possesso di ottantamila piastre. Si rivolse all’araldo che stava oltrepassando la tenda:

“Andrò io.” disse.

“Che follia!” gridò il padrone, che si trovava lì vicino. “Sei troppo giovane per gettare via così la tua vita. Rincorri l’araldo e digli che ritiri l’offerta.” ma il ragazzo scosse la testa e il mercante vide che sarebbe stato inutile tentare di persuaderlo.

“E va bene, sono affari tuoi.” disse alla fine. “Se devi andare, vai. Solo, se mai farai ritorno, ti darò un cammello carico di beni e in aggiunta il mio mulo migliore.” e toccandosi il turbante in segno di saluto, entrò nella tenda.

Lo aveva appena fatto che si vide una folla di uomini riversarsi fuori dall’accampamento.

“Come possiamo ringraziarti!” esclamarono, radunandosi attorno al ragazzo. “ I nostri cammelli e noi stessi stiamo quasi per morire di sete. Guarda! Qui c’è la fune che abbiamo portato per calarti.”

“Allora andiamo.” disse il ragazzo. E tutti si mossero.

Raggiunto il pozzo, la fune si fu annodata saldamente sotto le braccia, gli fu dato un grosso otre di pelle di capra e fu calato con delicatezza sul fondo del pozzo. Lì una limpida fonte gorgogliava dalle rocce e, chinandosi, stava per bere quando un enorme arabo gli comparve davanti e disse a voce alta:

“Vieni con me!”

Il ragazzo si alzò, certo che fosse giunta la sua ultima ora, ma siccome non poteva farci nulla, seguì l’arabo in una sala vividamente illuminata oltre il ruscello. Lì la sua guida sedette e, chiamando a sé due bambini, uno bianco e uno nero, disse allo straniero:

“Ho una domanda da rivolgerti. Se risponderai correttamente, la tua vita sarà risparmiata, altrimenti ti sarà tagliata la testa, così come a molti altri prima di te. Dimmi quale dei mie due bambini io penso sia più bello.”

La domanda non sembrava difficile perché mentre il bambino bianco era il più bel bambino che avesse mai visto, il fratello era brutto persino per un nero. Ma mentre stava per rispondere, gli balenò in mente il consiglio del vecchio e replicò rapidamente: ‘Colui che più amiamo è sempre il più bello.”

“Mi hai salvato!” gridò l’arabo, alzandosi in fretta e stringendo fra le braccia il ragazzo. “Se solo tu potessi immaginare quanto io abbia sofferto per la stupidità di tutte le persone alle quali ho posto la domanda, e e sono stato condannato da un malvagio genio a restare qui fino alla risposta giusta! Che cosa ti ha condotto in questo luogo e come posso ricompensarti per ciò che hai fatto per me?”

“Aiutandomi a portare abbastanza acqua per la carovana di ottanta mercanti con i loro cammelli, che stanno morendo di sete.” rispose il ragazzo.

“Niente di più facile,” disse l’arabo, “prendi queste tre mele e, quando avrai riempito il tuo otre e sarai pronto per essere risollevato, gettane una per terra. A metà strada gettane un’altra e in cima getta la terza. Se seguirai il mio consiglio, non ti accadrà nulla di male. E inoltre prendi queste tre melagrane, una verde, una rossa e una bianca. Un giorno ti saranno utili.”

Il ragazzo fece come gli era stato detto e rimise piede sul deserto roccioso in cui i mercanti lo stavano aspettando ansiosamente. Come erano tutti assetati! Ma persino dopo che ebbero bevuto i cammelli l’otre sembrava più colmo che mai.

Grati per la salvezza, i mercanti gli misero in mano le monete mentre il suo padrone gli disse di scegliere i beni che voleva e un mulo per trasportarli.

Così infine il figlio della vedova divenne ricco e, quando il mercante ebbe venduto le merci e fu tornato nella propria città d’origine, il suo servo assunse un uomo tramite il quale mandare alla moglie il denaro e il mulo.

‘Manderò anche le melagrane’ pensò ‘perché se le lascerò nel turbantesi rovineranno in pochi giorni.’ e le tirò fuori. Però i frutti erano svaniti e al loro posto c’erano tre pietre preziose, una verde, una rossa e una bianca.

Il ragazzo rimase a lungo con il mercante, che pian piano gli affidò i propri affari e gli diede una gran parte del denaro che guadagnava. Quando il suo padrone morì, il ragazzo desiderò tornare a casa, ma la la vedova lo pregò di restare ad aiutarla; un giorno si svegliò con un sussulto, rammentandosi che erano trascorsi vent’anni da quando se n’era andato.

“Voglio vedere mia moglie.” disse il mattino seguente alla padrona. “Se talvolta avrai bisogno di me, mandami un messaggero; nel frattempo ho istruito Hassan su ciò che deve fare.” e, montando sul cammello, se ne andò.

Poco dopo che aveva preso servizio presso il mercante, gli era nato un bambino e sia la principessa che la vecchia madre sgobbavano tutto il giorno per fornirgli cibo e abiti. Quando il denaro e le melagrane giunsero, per loro non fu più necessario lavorare ancora e la principessa vide vide subito che non erano frutti, ma pietre preziose di grande valore. La vecchia, non essendo avvezza come la nuora alla vista di gioielli, li prese per normali frutti e volle darli da mangiare al bambino. Si arrabbiò molto quando la principessa glieli prese rapidamente e li nascose nel vestito, invece andò al mercato e comprò le più belle tre melagrane che poté trovare e le mise in mano alla vecchia per il bambino.

Poi comprò splendidi abiti nuovi per tutti loro e quando furono vestiti, apparvero belli com’erano. Poi prese una delle pietre preziose che il marito le aveva mandato e la mise in un piccolo scrigno d’argento. Lo avvolse in un fazzoletto ricamato d’oro e riempì di monete d’oro e d’argento il borsellino della vecchia.

“Cara madre,” le disse, “vai a palazzo e offri il gioiello al re e se ti chiede che cosa vuoi in cambio, digli che vuoi un documento col sigillo regale il quale proclami che nessuno si intrometta in qualsiasi cosa tu decida di fare. Prima di lasciare il palazzo, distribuisci le monete tra i servitori.”

La vecchia prese lo scrigno e si diresse a palazzo. Nessuno aveva mai visto un rubino di tale bellezza e il più famoso gioielliere della città fu convocato per valutarlo. Tutto ciò che poté dire, fu:

“Se un bambino lanciasse in aria una pietra con tutte le forze e voi poteste ammucchiare tanto oro quanto in alto arrivasse la pietra, non sarebbe sufficiente per pagare questo rubino.”

A queste parole il volto del re si rabbuiò. Una volta visto il rubino, non poteva tollerare l’idea di separarsene, tuttavia tutto il denaro del tesoro reale non sarebbe bastato per pagarlo. Così rimase per un po’ in silenzio, domandandosi che offerta avrebbe potuto fare alla vecchia, e infine disse:

“Se non posso darti il suo valore in denaro, c’è qualcosa che vorresti in cambio?”

“Un documento, firmato di vostro pugno e con il vostro sigillo, il quale proclami che io possa fare ciò che voglio senza impedimenti o ostacoli.” rispose lei prontamente. Il re, ben felice di aver ottenuto ciò che bramava a un prezzo tanto basso, le diede senza indugio il documento. Allora la vecchia si congedò e tornò a casa.

La fama di questo meraviglioso rubino si sparse in lungo e in largo e alla casetta giunsero inviati per sapere se vi fossero più pietre da vendere. Ciascun re era ansioso di entrare in possesso del tesoro che ordinava al proprio messaggero di offrire di più e così la principessa vendette le due pietre rimaste per una somma di denaro così grande che se i pezzi d’oro fossero stati messi l’uno sull’altro sarebbero andati da qui alla luna. La prima cosa che fece fu costruire un palazzo a fianco della casetta, il quale fu innalzato su colonne d’oro nelle quali erano incastonati grossi diamanti che brillavano giorno e notte. Naturalmente la notizia di questo palazzo fu la prima che raggiunse il re suo padre al ritorno dalla guerra e si affrettò a vederlo. Sulla soglia c’era un ragazzo di vent’anni, suo nipote, sebbene entrambi non lo sapessero, e il re fu così soddisfatto alla vista del giovane che lo condusse con sé a palazzo e lo nominò comandante dell’intero esercito.

Non molto tempo dopo ciò, il figlio della vedova tornò nella terra natale. Lì, naturalmente, c’era la casetta in cui era vissuto con la madre, ma lo sfarzoso palazzo accanto era una novità per lui. Che ne era stato della moglie e della madre e chi dimorava in quel meraviglioso palazzo? Questi furono i primi pensieri che gli attraversarono la mente, ma non volendo tradirsi facendo domande ai passanti, si arrampicò su un albero che sorgeva di fronte al palazzo e osservò.

Di lì a poco una dama ne uscì e cominciò a cogliere un po’ di rose e di gelsomini sulla veranda. I vent’anni trascorsi da quando l’aveva vista svanirono in un istante e capì che era sua moglie, benché sembrasse giovane e bella come il giorno della sua partenza. Stava per balzare giù dall’albero e correre accanto a lei quando fu raggiunta da un ragazzo che le mise amorevolmente le braccia al collo. A quella vista il marito adirato prese l’arco ma, prima che potesse scagliare la freccia, il consiglio del vecchio gli tornò alla mente: ‘La pazienza è il primo passo sulla strada della felicità.” E abbassò di nuovo l’arco.

In quel momento la principessa la principessa si voltò e, traendo a sé la testa del ragazzo, lo baciò sulle guance. Per la seconda volta una collera cieca gli invase il cuore e prese l’arco dal ramo al quale era appeso quando le parole, udite tanti tempo prima, gli risuonarono nelle orecchie:

“Vince chi aspetta.” e l’arco tornò al suo posto. Poi, nell’aria silenziosa gli giunse il suono della voce del ragazzo:

“Madre, puoi dirmi qualcosa di mio padre? È ancora vivo e farà mai ritorno da noi?”

“Ahimè, figlio mio, come ti posso rispondere?” replicò la dama. “Sono trascorsi vent’anni da quando ci ha lasciti in cerca di fortuna e, in tutto questo tempo, solo una volta ho avuto notizie di lui. Ma che cosa te lo riporta proprio ora alla mente?”

“La notte scorsa ho sognato che fosse qui,” disse il ragazzo, “ e allora ho rammentato ciò che avevo dimenticato a lungo, cioè che ho un padre sebbene la sua vera storia mi sia sconosciuta. E ora ti prego, dimmi tutto ciò che lo riguarda.”

E sotto il gelsomino il figlio conobbe la storia di suo padre e anche l’uomo sull’albero ascoltò.

Quando la storia fu terminata, mentre si torceva le mani affranto, il ragazzo esclamò: “Sono il generale in capo, tu sei la figlia del re e possediamo il più sfarzoso palazzo del mondo, tuttavia mio padre vive non sappiamo dove e, per quanto ne sappiamo, potrebbe essere in miseria. Domani chiederò al re di darmi dei soldati e lo cercherò in tutto il mondo finché lo troverò.”

Allora l’uomo scese dall’albero e strinse fra le braccia la moglie e il figlio. Parlarono per tutta la notte e quando sorse il sole stavano ancora parlando. Appena fu il momento opportuno, egli andò a palazzo a porgere i propri omaggi al re e a informarlo di tutto ciò che era accaduto e chi essi fossero in realtà. Il re fu sopraffatto dalla gioia al pensiero che la figlia, che aveva da tempo perdonato e dolorosamente perduta, vivesse alle sue porte e oltretutto fosse la madre del giovane che gli era così caro. “Era scritto in anticipo,” esclamò il re, “tu sei mio genero agli occhi del mondo e sarai re dopo di me.”

L’uomo chinò il capo.

Aveva atteso e aveva vinto.

Da Racconti armeni raccolti da Fréderic Macler.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)