Soria Moria Castle

(MP3-11,6 MB 24' 22")

THERE was once upon a time a couple of folks who had a son called Halvor. Ever since he had been a little boy he had been unwilling to do any work, and had just sat raking about among the ashes. His parents sent him away to learn several things, but Halvor stayed nowhere, for when he had been gone two or three days he always ran away from his master, hurried off home, and sat down in the chimney corner to grub among the ashes again.

One day, however, a sea captain came and asked Halvor if he hadn't a fancy to come with him and go to sea, and behold foreign lands. And Halvor had a fancy for that, so he was not long in getting ready.

How long they sailed I have no idea, but after a long, long time there was a terrible storm, and when it was over and all had become calm again, they knew not where they were, for they had been driven away to a strange coast of which none of them had any knowledge.

As there was no wind at all they lay there becalmed, and Halvor asked the skipper to give him leave to go on shore to look about him, for he would much rather do that than lie there and sleep.

'Dost thou think that thou art fit to go where people can see thee?' said the skipper; 'thou hast no clothes but those rags thou art going about in!'

Halvor still begged for leave, and at last got it, but he was to come back at once if the wind began to rise.

So he went on shore, and it was a delightful country; whithersoever he went there were wide plains with fields and meadows, but as for people, there were none to be seen. The wind began to rise, but Halvor thought that he had not seen enough yet, and that he would like to walk about a little longer, to try if he could not meet somebody. So after a while he came to a great highway, which was so smooth that an egg might have been rolled along it without breaking. Halvor followed this, and when evening drew near he saw a big castle far away in the distance, and there were lights in it. So as he had now been walking the whole day and had not brought anything to eat away with him, he was frightfully hungry. Nevertheless, the nearer he came to the castle the more afraid he was.

A fire was burning in the castle, and Halvor went into the kitchen, which was more magnificent than any kitchen he had ever yet beheld. There were vessels of gold and silver, but not one human being was to be seen. When Halvor had stood there for some time, and no one had come out, he went in and opened a door, and inside a Princess was sitting at her wheel spinning.

'Nay!' she cried, 'can Christian folk dare to come hither? But the best thing that you can do is to go away again, for if not the Troll will devour you. A Troll with three heads lives here.'

'I should have been just as well pleased if he had had four heads more, for I should have enjoyed seeing the fellow,' said the youth; 'and I won't go away, for I have done no harm, but you must give me something to eat, for I am frightfully hungry.'

When Halvor had eaten his fill, the Princess told him to try if he could wield the sword which was hanging on the wall, but he could not wield it, nor could he even lift it up.

'Well, then, you must take a drink out of that bottle which is hanging by its side, for that's what the Troll does whenever he goes out and wants to use the sword,' said the Princess.

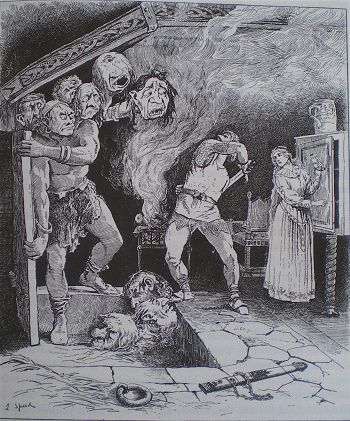

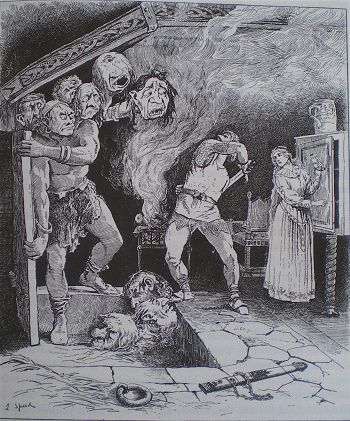

Halvor took a draught, and in a moment he was able to swing the sword about with perfect ease. And now he thought it was high time for the Troll to make his appearance, and at that very moment he came, panting for breath.

Halvor got behind the door.

' Hutetu !' said the Troll as he put his head in at the door. 'It smells just as if there were Christian man's blood here!'

'Yes, you shall learn that there is!' said Halvor, and cut off all his heads.

The Princess was so rejoiced to be free that she danced and sang, but then she remembered her sisters, and said: 'If my sisters were but free too!'

'Where are they?' asked Halvor.

So she told him where they were. One of them had been taken away by a Troll to his castle, which was six miles off, and the other had been carried off to a castle which was nine miles farther off still.

'But now,' said she, 'you must first help me to get this dead body away from here.'

Halvor was so strong that he cleared everything away, and made all clean and tidy very quickly. So then they ate and drank, and were happy, and next morning he set off in the grey light of dawn. He gave himself no rest, but walked or ran the livelong day. When he came in sight of the castle he was again just a little afraid. It was much more splendid than the other, but here too there was not a human being to be seen. So Halvor went into the kitchen, and did not linger there either, but went straight in.

'Nay! do Christian folk dare to come here?' cried the second Princess. 'I know not how long it is since I myself came, but during all that time I have never seen a Christian man. It will be better for you to depart at once, for a Troll lives here who has six heads.'

'No, I shall not go,' said Halvor; 'even if he had six more I would not.'

'He will swallow you up alive,' said the Princess.

But she spoke to no purpose, for Halvor would not go; he was not afraid of the Troll, but he wanted some meat and drink, for he was hungry after his journey. So she gave him as much as he would have, and then she once more tried to make him go away.

'No,' said Halvor, 'I will not go, for I have not done anything wrong, and I have no reason to be afraid.'

'He won't ask any questions about that,' said the Princess, 'for he will take you without leave or right; but as you will not go, try if you can wield that sword which the Troll uses in battle.'

He could not brandish the sword; so the Princess said that he was to take a draught from the flask which hung by its side, and when he had done that he could wield the sword.

Soon afterwards the Troll came, and he was so large and stout that he was forced to go sideways to get through the door. When the Troll got his first head in he cried: 'Hutetu! It smells of a Christian man's blood here!'

With that Halvor cut off the first head, and so on with all the rest. The Princess was now exceedingly delighted, but then she remembered her sisters, and wished that they too were free. Halvor thought that might be managed, and wanted to set off immediately; but first he had to help the Princess to remove the Troll's body, so it was not until morning that he set forth on his way.

It was a long way to the castle, and he both walked and ran to get there in time. Late in the evening he caught sight of it, and it was very much more magnificent than either of the others. And this time he was not in the least afraid, but went into the kitchen, and then straight on inside the castle. There a Princess was sitting, who was so beautiful that there was never

anyone to equal her. She too said what the others had said, that no Christian folk had ever been there since she had come, and entreated him to go away again, or else the Troll would swallow him up alive. The Troll had nine heads, she told him.

'Yes, and if he had nine added to the nine, and then nine more still, I would not go away,' said Halvor, and went and stood by the stove.

The Princess begged him very prettily to go lest the Troll should devour him; but Halvor said, 'Let him come when he will.'

So she gave him the Troll's sword, and bade him take a drink from the flask to enable him to wield it.

At that same moment the Troll came, breathing hard, and he was ever so much bigger and stouter than either of the others, and he too was forced to go sideways to get in through the door.

'Hutetu! what a smell of Christian blood there is here!' said he.

Then Halvor cut off the first head, and after that the others, but the last was the toughest of them all, and it was the hardest work that Halvor had ever done to get it off, but he still believed that he would have strength enough to do it.

And now all the Princesses came to the castle, and were together again, and they were happier than they had ever been in their lives; and they were delighted with Halvor, and he with them, and he was to choose the one he liked best; but of the three sisters the youngest loved him best.

But Halvor went about and was so strange and so mournful and quiet that the Princesses asked what it was that he longed for, and if he did not like to be with them. He said that he did like to be with them, for they had enough to live on, and he was very comfortable there; but he longed to go home, for his father and mother were alive, and he had a great desire to see them again.

They thought that this might easily be done.

'You shall go and return in perfect safety if you will follow our advice,' said the Princesses.

So he said that he would do nothing that they did not wish.

Then they dressed him so splendidly that he was like a King's son; and they put a ring on his finger, and it was one which would enable him to go there and back again by wishing, but they told him that he must not throw it away, or name their names; for if he did, all his magnificence would be at an end, and then he would never see them more.

'If I were but at home again, or if home were but here!' said Halvor, and no sooner had he wished this than it was granted. Halvor was standing outside his father and mother's cottage before he knew what he was about. The darkness of night was coming on, and when the father and mother saw such a splendid and stately stranger walk in, they were so startled that they both began to bow and curtsey.

Halvor then inquired if he could stay there and have lodging for the night. No, that he certainly could not. 'We can give you no such accommodation,' they said, 'for we have none of the things that are needful when a great lord like you is to be entertained. It will be better for you to go up to the farm. It is not far off, you can see the chimney-pots from here, and there they have plenty of everything.'

Halvor would not hear of that, he was absolutely determined to stay where he was; but the old folks stuck to what they had said, and told him that he was to go to the farm, where he could get both meat and drink, whereas they themselves had not even a chair to offer him.

'No,' said Halvor, 'I will not go up there till early to-morrow morning; let me stay here to-night. I can sit down on the hearth.'

They could say nothing against that, so Halvor sat down on the hearth, and began to rake about among the ashes just as he had done before, when he lay there idling away his time.

They chattered much about many things, and told Halvor of this and of that, and at last he asked them if they had never had any child.

'Yes,' they said; they had had a boy who was called Halvor, but they did not know where he had gone, and they could not even say whether he were dead or alive.

'Could I be he?' said Halvor.

'I should know him well enough,' said the old woman rising. 'Our Halvor was so idle and slothful that he never did anything at all, and he was so ragged that one hole ran into another all over his clothes. Such a fellow as he was could never turn into such a man as you are, sir.'

In a short time the old woman had to go to the fireplace to stir the fire, and when the blaze lit up Halvor, as it used to do when he was at home raking up the ashes, she knew him again.

'Good Heavens! is that you, Halvor?' said she, and such great gladness fell on the old parents that there were no bounds to it. And now he had to relate everything that had befallen him, and the old woman was so delighted with him that she would take him up to the farm at once to show him to the girls who had formerly looked down on him so. She went there first, and Halvor followed her. When she got there she told them how Halvor had come home again, and now they should just see how magnificent he was. 'He looks like a prince,' she said.

'We shall see that he is just the same ragamuffin that he was before,' said the girls, tossing their heads.

At that same moment Halvor entered, and the girls were so astonished that they left their kirtles lying in the chimney corner, and ran away in nothing but their petticoats. When they came in again they were so shamefaced that they hardly dared to look at Halvor, towards whom they had always been so proud and haughty before.

'Ay, ay! you have always thought that you were so pretty and dainty that no one was equal to you,' said Halvor, 'but you should just see the eldest Princess whom I set free. You look like herds-women compared with her, and the second Princess is also much prettier than you; but the youngest, who is my sweetheart, is more beautiful than either sun or moon. I wish to Heaven they were here, and then you would see them.'

Scarcely had he said this before they were standing by his side, but then he was very sorrowful, for the words which they had said to him came to his mind.

Up at the farm a great feast was made ready for the Princesses, and much respect paid to them, but they would not stay there.

'We want to go down to your parents,' they said to Halvor, 'so we will go out and look about us.'

He followed them out, and they came to a large pond outside the farm-house. Very near the water there was a pretty green bank, and there the Princesses said they would sit down and while away an hour, for they thought that it would be pleasant to sit and look out over the water, they said.

There they sat down, and when they had sat for a short time the youngest Princess said, 'I may as well comb your hair a little, Halvor.'

So Halvor laid his head down on her lap, and she combed it, and it was not long before he fell asleep. Then she took her ring from him and put another in its place, and then she said to her sisters: 'Hold me as I am holding you. I would that we were at Soria Moria Castle.'

When Halvor awoke he knew that he had lost the Princesses, and began to weep and lament, and was so unhappy that he could not be comforted. In spite of all his father's and mother's entreaties, he would not stay, but bade them farewell, saying that he would never see them more, for if he did not find the Princess again he did not think it worth while to live.

He again had three hundred dollars, which he put into his pocket and went on his way. When he had walked some distance he met a man with a tolerably good horse. Halvor longed to buy it, and began to bargain with the man.

'Well, I have not exactly been thinking of selling him,' said the man, 'but if we could agree, perhaps——'

Halvor inquired how much he wanted to have for the horse.

'I did not give much for him, and he is not worth much; he is a capital horse to ride, but good for nothing at drawing; but he will always be able to carry your bag of provisions and you too, if you walk and ride by turns.' At last they agreed about the price, and Halvor laid his bag on the horse, and sometimes he walked and sometimes he rode. In the evening he came to a green field, where stood a great tree, under which he seated himself. Then he let the horse loose and lay down to sleep, but before he did that he took his bag off the horse. At daybreak he set off again, for he did not feel as if he could take any rest. So he walked and rode the whole day, through a great wood where there were many green places which gleamed very prettily among the trees. He did not know where he was or whither he was going, but he never lingered longer in any place than was enough to let his horse get a little food when they came to one of these green spots, while he himself took out his bag of provisions.

So he walked and he rode, and it seemed to him that the wood would never come to an end. But on the evening of the second day he saw a light shining through the trees.

'If only there were some people up there I might warm myself and get something to eat,' thought Halvor.

When he got to the place where the light had come from, he saw a wretched little cottage, and through a small pane of glass he saw a couple of old folks inside. They were very old, and as grey-headed as a pigeon, and the old woman had such a long nose that she sat in the chimney corner and used it to stir the fire.

'Good evening! good evening!' said the old hag; 'but what errand have you that can bring you here? No Christian folk have been here for more than a hundred years.'

So Halvor told her that he wanted to get to Soria Moria Castle, and inquired if she knew the way thither.

'No,' said the old woman, 'that I do not, but the Moon will be here presently, and I will ask her, and she will know. She can easily see it, for she shines on all things.'

So when the Moon stood clear and bright above the tree-tops the old woman went out. 'Moon! Moon!' she screamed. 'Canst thou tell me the way to Soria Moria Castle?'

'No,' said the Moon, 'that I can't, for when I shone there, there was a cloud before me.'

'Wait a little longer,' said the old woman to Halvor, 'for the West Wind will presently be here, and he will know it, for he breathes gently or blows into every corner.'

'What! have you a horse too?' she said when she came in again. 'Oh! let the poor creature loose in our bit of fenced-in pasture, and don't let it stand there starving at our very door. But won't you exchange him with me? We have a pair of old boots here with which you can go fifteen quarters of a mile at each step. You shall have them for the horse, and then you will be able to get sooner to Soria Moria Castle.'

Halvor consented to this at once, and the old woman was so delighted with the horse that she was ready to dance. 'For now I, too, shall be able to ride to church,' she said. Halvor could take no rest, and wanted to set off immediately; but the old woman said that there was no need to hasten. 'Lie down on the bench and sleep a little, for we have no bed to offer you,' said she, 'and I will watch for the coming of the West Wind.'

Ere long came the West Wind, roaring so loud that the walls creaked.

The old woman went out and cried:

'West Wind! West Wind! Canst thou tell me the way to Soria Moria Castle? Here is one who would go thither.'

'Yes, I know it well,' said the West Wind. 'I am just on my way there to dry the clothes for the wedding which is to take place. If he is fleet of foot he can go with me.'

Out ran Halvor.

'You will have to make haste if you mean to go with me,' said the West Wind; and away it went over hill and dale, and moor and morass, and Halvor had enough to do to keep up with it.

'Well, now I have no time to stay with you any longer,' said the West Wind, 'for I must first go and tear down a bit of spruce fir before I go to the bleaching-ground to dry the clothes; but just go along the side of the hill, and you will come to some girls who are standing there washing clothes, and then you will not have to walk far before you are at Soria Moria Castle.'

Shortly afterwards Halvor came to the girls who were standing washing, and they asked him if he had seen anything of the West Wind, who was to come there to dry the clothes for the wedding.

'Yes,' said Halvor, 'he has only gone to break down a bit of spruce fir. It won't be long before he is here.' And then he asked them the way to Soria Moria

Castle. They put him in the right way, and when he came in front of the castle it was so full of horses and people that it swarmed with them. But Halvor was so ragged and torn with following the West Wind through bushes and bogs that he kept on one side, and would not go among the crowd until the last day, when the feast was to be held at noon.

So when, as was the usage and custom, all were to drink to the bride and the young girls who were present, the cup-bearer filled the cup for each in turn, both bride and bridegroom, and knights and servants, and at last, after a very long time, he came to Halvor. He drank their health, and then slipped the ring which the Princess had put on his finger when they were sitting by the waterside into the glass, and

ordered the cup-bearer to carry the glass to the bride from him and greet her.

Then the Princess at once rose up from the table, and said, 'Who is most worthy to have one of us—he who has delivered us from the Trolls or he who is sitting here as bridegroom?'

There could be but one opinion as to that, everyone thought, and when Halvor heard what they said he was not long in flinging off his beggar's rags and arraying himself as a bridegroom.

'Yes, he is the right one,' cried the youngest Princess when she caught sight of him; so she flung the other out of the window and held her wedding with Halvor.

From P. C. Asbjornsen.

Il castello di Soria Moria

C'era una volta una coppia che aveva un figlio di nome Halvor. Sin da quando era piccolo, era sempre stato restio a fare qualsiasi lavoro e stava solo seduto a rovistare nella cenere. I suoi genitori lo avviarono a imparare vari mestieri, ma Halvor non rimaneva da nessuna parte perché dopo che erano passati due o tre giorni scappava sempre via dal suo padrone, affrettandosi casa, e sedeva in un angolo del camino a frugare di nuovo in mezzo alla cenere.

Un giorno, in ogni modo, arrivò un capitano e chiese a Halvor se non avesse voglia andare per mare con lui e vedere terre straniere. A Halvor venne voglia, così non ci mise molto a esser pronto.

Non ho idea di quanto abbiano navigato, ma dopo un bel po' di tempo ci fu una terribile tempesta e, quando fu finita e tutto fu tornato di nuovo calmo, non capirono dove fossero perché erano stati condotti verso una costa straniera della quale nessuno di loro sapeva nulla.

Siccome non c'era più vento, rimasero lì in bonaccia e Halvor chiese al capitano che gli permettesse di scendere a terra a guardarsi attorno perché voleva far qualcosa di più che starsene lì e dormire.

"E pensi di essere in condizioni adatte per andare dove la gente possa vederti?" disse il capitano; "Tu che non hai abiti al di fuori degli stracci che indossi!"

Halvor lo pregò ancora di lasciarlo andare e alla fine ci riuscì, ma doveva tornare indietro appena si fosse alzato il vento.

Così andò sulla spiaggia, era proprio un paese assai gradevole; ovunque andasse c'erano vaste pianure con campi e prati, ma, in quanto alla gente, nessuno era in vista. Cominciò a soffiare il vento, ma Halvor pensava di non aver visto ancora abbastanza e che gli sarebbe piaciuto camminare ancora un po', per vedere se incontrasse qualcuno. Così dopo un po' arrivò a una grande strada, così liscia che un uovo avrebbe potuto rotolarci sopra senza rompersi. Halvor la seguì e, verso sera, vide un grande castello in lontananza le cui luci erano accese. Poiché aveva camminato per tutto il giorno e non aveva portato nulla con sé da mangiare, era assai affamato. Tuttavia, più si avvicinava al castello e più aveva paura.

Nel castello ardeva un fuoco e Halvor andò in cucina, la cucina più magnifica di ogni altra che avesse mai visto. C'erano recipienti d'oro e d'argento, ma non si vedeva un essere umano. Dopo essere rimasto lì per un po' di tempo senza che fosse venuto nessuno, Halvor andò ad aprire una porta e dentro era seduta una principessa che stava filando.

"No!" gridò, "come può osare un cristiano venire qui? La cosa migliore che tu possa fare è andartene via, affinché il troll non ti divori. Qui vive un troll con tre teste."

"Sarei ugualmente soddisfatto anche se avesse quattro teste perché mi piacerebbe vedere un tipo simile," disse il ragazzo; "E non intendo andare via perché non ho fatto nulla di male, anzi, devi darmi qualcosa da mangiare perché sono terribilmente affamato."

Quando Halvor ebbe mangiato a sazietà, la principessa gli disse di provare se riuscisse a brandire la spada che era appesa al muro, ma lui non poté farlo e non gli riuscì neppure di sollevarla.

"Be', allora, devi bere un sorso da quella bottiglia che è appesa lì accanto, perché il troll lo fa ogni volta che esce e vuole usare la spada." disse la principessa.

Halvor ne prese una sorsata e in attimo fu capace di maneggiare la spada con perfetta padronanza. E adesso pensò che fosse proprio il momento che il troll comparisse ed ecco che davvero venne, riprendendo fiato.

Halvor si mise dietro la porta.

"Uccio uccio (1)!" disse il troll appena ebbe infilato la test nella porta. "Qui sento odore di sangue di cristianuccio!"

"Oh, sì, ti accorgerai che c'é!" disse Halvor e gli tagliò tutte le teste.

La principessa si rallegrò talmente di essere libera che danzò e cantò, ma poi si ricordò delle sorelle e disse: "Se anche le mie sorelle fossero libere!"

"Dove sono?" chiese Halvor.

Così lei gli raccontò dove si trovassero. Una di loro era stata portata via da un troll nel suo castello che sorgeva a sei miglia da lì, un'altra era stata condotta in un castello lontano nove miglia.

"Adesso, " disse lei, "per prima cosa mi devi aiutare a far sparire da qui questo corpo."

Halvor era così forte che fece piazza pulita e pulì tutto in un baleno. Poi mangiarono e bevvero, felici e contenti, e la mattina seguente si mise in cammino nella grigia luce dell'alba. Non si concesse riposo, camminò o corse per tutto il giorno. Quando fu in vista del castello ebbe di nuovo un po' di paura. Era ancora più splendido dell'altro, ma anche lì non si vedeva anima viva. Così Halvor entrò in cucina, ma non vi si fermò e tirò dritto.

"No! Come può osare un cristiano venire qui?" gridò la seconda principessa. "Non so più da quanto sono venuta qui, ma per tutto questo tempo non ho mai visto un cristiano. Sarà meglio per te che te ne vada perché qui vive un troll con sei teste."

"Non me ne andrò," disse Halvor; "non lo farei nemmeno se avesse altre sei teste."

"Ti inghiottirà vivo." Disse la principessa.

Ma la principessa parlò invano perché Halvor non volle andarsene; non aveva paura del troll, ma voleva da mangiare e da bere perché era affamato dopo quel viaggio. Così lei gli dette quanto voleva e poi, ancora una volta, tentò di mandarlo via.

"No, " disse Halvor, "Non me ne andrò perché non ho fatto nulla di sbagliato e non ho motivo di aver paura."

"Non ti chiederà nulla riguardo a ciò," disse la principessa, "perché ti prenderà senza curarsi che sia giusto o sbagliato; ma se non vuoi andartene, prova a brandire questa spada che il troll una in battaglia."

Halvor non ce la fece a brandire la spada; così la principessa gli disse che doveva bere un sorso dalla fiasca che le era appesa accanto; quando l'ebbe fatto, ecco che riuscì a brandire la spada.

Poco dopo arrivò il troll, era così grosso e robusto che doveva girarsi di lato per passare attraverso la porta. Quando il troll infilò la prima testa, gridò: " Uccio, uccio! Qui sento odore di sangue di cristianuccio!"

Al che Halvor gli tagliò la prima testa e poi tutte le altre. La principessa era veramente lieta, ma si ricordò delle sue sorelle e desiderò che anche loro fossero libere. Halvor pensò che ci si potesse riuscire e voleva partire immediatamente, ma prima dovette aiutare la principessa a spostare il corpo del troll e così non si mise in cammino fino al mattino seguente.

La strada per il castello era lunga e Halvor camminò e corse per arrivare in tempo. In tarda serata poté vedere il castello; era ancora più magnifico degli altri due. A questo punto non aveva quasi più paura, andò in cucina e poi entrò subito nel castello. C'era una principessa seduta, era così bella che non ne esisteva una uguale a lei. Anche lei gli disse le

medesime cose delle altre, che nessun cristiano era mai arrivato lì da quando lei vi si trovava e lo supplicò di andarsene o il troll se lo sarebbe mangiato vivo. Il troll aveva nove teste, gli disse.

"Bene, e anche se ne avesse altre nove oltre quelle nove, e poi altre nove ancora, io non me ne andrei." disse Halvor e andò a mettersi vicino alla stufa.

La principessa lo pregò assai graziosamente affinché se ne andasse prima che il troll potesse divorarlo; Halvor disse: "Lascia che venga quando vuole."

Allora lei gli diede la spada del troll e gli offrì un sorso dalla fiasca perché riuscisse a brandirla.

In quel momento il troll entrò, ansimando forte, ed era ancor più grosso e robusto degli altri; anche lui dovette girarsi di fianco per passare attraverso la porta.

"Uccio, uccio! Qui sento odore di sangue di cristianuccio!" disse.

Allora Halvor gli tagliò la prima testa e poi tutte le altre; l'ultima fu la più resistente di tutte e Halvor dovette faticare duramente per farla cadere, ma sapeva di avere abbastanza forza per riuscirci.

Ora tutte le principesse vennero al castello e furono di nuovo insieme, felici come mai lo erano state in vita loro; erano lietissime di stare con lui, e lui di stare con loro; avrebbe potuto scegliere quella che preferiva, ma delle tre sorelle era la più giovane che lo amava di più.

Ma Halvor se ne andava in giro e divenne così strano, triste e silenzioso che le principesse gli chiesero che cosa desiderasse e se non gli piacesse stare con loro. Lui rispose che gli piaceva stare con loro, che avevano abbastanza per vivere e lui si sentiva a proprio agio lì; ma desiderava tornare a casa, perché là vivevano suo padre e sua madre e lui aveva una gran voglia di rivederli.

Le principesse pensarono che lo si poteva accontentare facilmente.

"Andrai e tornerai in tutta sicurezza se seguirai il nostro consiglio." dissero le principesse.

Lui rispose che non avrebbe mai fatto nulla che loro non volessero.

Allora lo vestirono splendidamente, come un figlio di re, gli misero al dito un anello che aveva il potere di portarlo avanti e indietro secondo i suoi desideri, ma, gli dissero, non doveva gettarlo via né nominarle; se lo avesse fatto, tutta quella magnificenza sarebbe svanita e non le avrebbe riviste mai più.

"Se fossi di nuovo a casa o casa mia fosse qui!" disse Halvor, e l'aveva appena desiderato che fu esaudito. Halvor stava davanti alla casetta di suo padre e di sua madre prima ancora di capire che cosa fosse accaduto. Le tenebre della notte stavano calando e quando il padre e la madre videro avanzare un così splendido e imponente straniero, furono così sorpresi che entrambi cominciarono a fare inchini e riverenze.

Allora Halvor chiese se si sarebbe potuto fermare e avere alloggio per la notte. No, non si poteva proprio. "Non possiamo offrirvi una degna sistemazione," dissero, "perché non possediamo nulla di ciò che serve quando un grande signore come voi deve essere ricevuto. Sarebbe meglio per voi salire alla fattoria. Non è troppo lontana, potete vederne il comignolo da qui, e là abbondanza di tutto."

Halvor non ne voleva sapere, era assolutamente deciso a stare dove si trovava; ma i due vecchi si ostinavano su ciò che avevano detto e gli ripetevano che doveva andare alla fattoria, dove avrebbe trovato cibo e bevande, mentre loro non avevano neppure una sedia da offrirgli.

"No," disse Halvor, "non salirò lassù fino a domattina presto; lasciatemi stare qui stanotte. Posso sedermi per terra."

Non poterono dire nulla in contrario, così Halvor sedette per terra e cominciò a rovistare la cenere proprio come faceva prima, quando giaceva lì oziando.

Chiacchierarono di molte cose, parlarono ad Halvor di questo e di quello e infine lui chiese se non avessero mai avuto figli.

"Sì, "dissero; avevano avuto un figlio che si chiamava Halvor, ma non sapevano dove fosse andato, non poteva dire se fosse vivo o morto.

"Potrei essere io?" disse Halvor.

"Lo conosco abbastanza bene, " disse la donna, alzandosi. "Il nostro Halvor era così pigro e infingardo che non faceva mai nulla, ed era così straccione che i buchi si rincorrevano sui suoi panni. Un tipo come lui non si sarebbe mai trasformato in un signore quale voi siete."

Poco dopo la vecchia raggiunse il camino per attizzare il fuoco e, quando le fiamme illuminarono Halvor, proprio com'era solito quando se ne stava in casa a rimestare la cenere, lei lo riconobbe.

"Giusto cielo! Sei, tu, Halvor?" disse e i vecchi genitori furono invasi da una contentezza senza limiti. Ora lui dovette raccontare ogni cosa che gli era accaduta e la vecchia era così contenta che avrebbe voluto portarlo subito alla fattoria e mostrarlo alle ragazze che prima lo avevano sempre guardato dall'alto in basso. Ci andò lei per prima e Halvor la seguì. Quando fu là, disse loro che Halvor era tornato di nuovo a casa e avrebbero dovuto vedere quanto fosse magnifico. "Sembra un principe." disse.

"Vedremo che è proprio il solito straccione che è sempre stato." dissero le ragazze, scuotendo il capo.

In quel momento Halvor entrò, le ragazze rimasero così sbalordite che abbandonarono le loro bluse in un angolo del focolare e corsero via con addosso niente altro che le loro sottovesti. Quando tornarono, erano così vergognose che a malapena osavano guardare Halvor, verso il quale prima si erano mostrate sempre orgogliose e altezzose.

"Ah, ah! Avete sempre pensato di essere così belle e aggraziate che nessuna potesse essere come voi, " disse Halvor, "ma se vedeste le principesse che ho liberato. Sembrate mandriane in confronto a loro; la seconda principessa è anche più bella di voi, ma la più giovane, che è la mia fidanzata, è bella più del sole e della luna. Volesse il Cielo che fossero qui, allora le vedreste."

Aveva appena parlato che eccole apparire al suo fianco; ma ne fu molto dispiaciuto, perché gli erano tornate in mente le parole che gli avevano detto.

Su alla fattoria fu organizzata una grande festa per le principesse, e furono trattate con ogni riguardo, ma loro non volevano stare lì.

"Vogliamo scendere dai tuoi genitori, " dissero a Halvor, "così andremo in giro e ci guarderemo attorno."

Lui le seguì e loro andarono a un grande stagno oltre la fattoria. Assai vicino all'acqua c'era una bella riva verde e lì le principesse gli dissero che sarebbero volute sedersi e starsene un'oretta, perché pensavano che fosse assai piacevole sedere e guardare l'acqua, dissero.

Sedettero e quando vi furono rimasti per un po' di tempo, la principessa più giovane disse: "Potrei pettinarti un po' i capelli, Halvor."

Così Halvor posò la testa sul suo grembo e lei lo pettinò, e di lì a poco si addormentò. Allora lei gli prese l'anello e lo sostituì con un altro, poi disse alle sorelle: "Tenetevi a me come io mi tengo a voi. Vorrei che fossimo al castello di Soria Moria."

Quando Halvor si svegliò, capì di aver perduto le principesse e cominciò a piangere e a lamentarsi, ed era così infelice che non poteva trovare conforto. Nonostante le suppliche del padre e della madre, non volle restare; disse loro addio, aggiungendo che non li avrebbe più rivisti perché, se non avesse ritrovato la principessa, pensava che non valesse la pena di vivere.

Gli erano rimaste trecento corone, le mise nella tasca e riprese il cammino. Quando ebbe camminato per un bel tratto, incontrò un uomo con un cavallo abbastanza buono. Halvor desiderava comprarlo e si mise a mercanteggiare con l'uomo.

"Beh, non avevo proprio pensato di venderlo, " disse l'uomo, "ma se possiamo metterci d'accordo, forse…"

Halvor chiese quanto volesse per il cavallo.

"Non l'ho pagato molto e non vale molto; è un cavallo di prim'ordine per cavalcare, ma non è buono da tiro; sarà sempre capace di portare il vostro sacco di provviste e anche voi, se alternativamente cavalcherete e camminerete." Alla fine si accordarono sul prezzo e Halvor caricò la borsa sul cavallo; e a volte camminò, a volte cavalcò. La sera giunsero in un campo verde in cui sorgeva un grande albero, sotto il quale sedette. Lasciò libero il cavallo e si sdraiò a dormire, ma prima di farlo, tirò giù dal cavallo la borsa. Allo spuntare del giorno si rimise in cammino perché non se la sentiva di stare fermo. Così camminò e cavalcò l'intero giorno, attraverso un grande bosco in cui c'erano molte radure verdi che luccicavano assai gradevolmente tra gli alberi. Non sapeva dove fosse o dove stesse andando, ma non si tratteneva in un posto più a lungo di quanto servisse al suo cavallo per mangiare; quando arrivava in una di quelle radure, anche lui prendeva il sacco delle provviste.

Così camminava e cavalcava, e gli sembrava che il bosco non dovesse avere mai fine. Ma la sera del secondo giorno vide brillare tra gli alberi una luce.

"Se solo là ci fosse qualcuno alzato, potrei riscaldarmi e avere qualcosa da mangiare." pensò Halvor.

Quando raggiunse il posto dal quale proveniva la luce, vide una casetta malmessa e, attraverso un piccolo vetro vide all'interno una coppia di vecchi. Erano assai vecchi, le teste grigie come un piccione, e la vecchia aveva un naso tanto lungo che usava per attizzare il fuoco, seduta in un angolo del camino.

"Buonasera! Buonasera!" disse la vecchia megera; "Che razza di ramingo sei se puoi arrivare fin qui? Non sono più venuti cristiani da almeno cento anni."

Così Halvor le raccontò che voleva trovare il castello di Soria Moria e le chiese se conoscesse la strada.

"No," disse la vecchia, "non la so, ma la luna sorgerà presto e glielo chiederò, lei lo saprà. Può vederlo facilmente, perché risplende su ogni cosa."

Così quando la luna sorse limpida e lucente sulle cime degli alberi, la vecchia uscì da casa. "Luna! Luna!" gridò. "Puoi dirmi la strada per il castello di Soria Moria?"

"No, " disse la luna, "non posso perché quando soffiai là, c'era una nuvola davanti a me."

"Aspetta ancora un po'", disse la vecchia a Halvor, "perché il vento dell'ovest presto sarà qui e lui potrebbe saperlo, visto che spira dolcemente o soffia in ogni angolo."

"Che cosa? Hai un cavallo?" disse, quando ritornò. "Lascia che quella povera creatura libera di brucare nel prato, non tenerla qui a patire la fame vicino alla porta. Vorresti scambiarlo con me? Ho un paio di stivali con i quali puoi fare quindici quarti di miglio ad ogni passo. Li avrai in cambio del cavallo e presto potrai arrivare al castello di Soria Moria."

Halvor accettò subito e la vecchia fu così contenta di avere il cavallo che si mise a ballare. "Adesso potrò andare in chiesa a cavallo." disse. Halvor non si sarebbe voluto fermare e voleva partire immediatamente; ma la vecchia gli disse che non c'era fretta. "Sdraiati sulla panca e dormi un po', perché non abbiamo un letto da offrirti, " gli disse, "io aspetterò l'arrivo del vento dell'ovest."

Di lì a non molto arrivò il vento dell'ovest, ruggendo così forte che i muri scricchiolarono.

La vecchia uscì e gridò:

"Vento dell'ovest! Vento dell'ovest! Non puoi dirmi la strada per il castello di Soria Moria? Qui c'è uno che vorrebbe andarci."

"Sì, la conosco bene, " disse il vento dell'ovest. "Devo giusto andarci ad asciugare i panni per le nozze che vi si svolgeranno. Se ha buone gambe, può venire con me."

Halvor corse fuori.

"Devi sbrigarti, se vuoi venire con me," disse il vento dell'ovest; e si lanciò sulla collina e sulla valle, sulla brughiera e sulla palude, e Halvor ebbe abbastanza da fare per tenergli dietro.

"Beh, adesso non ho più tempo di stare ancora con te, " disse il vento dell'ovest, "perché devo andare ad abbattere un po' di abeti rossi prima di raggiungere il prato per asciugare i panni; devi solo seguire il fianco della collina e arriverai da alcune ragazze che si trovano lì a lavare i panni; allora non dovrai camminare ancora a lungo per giungere al castello di Soria Moria."

Subito dopo Halvor raggiunse le ragazze che stavano lavando e gli chiesero se sapesse nulla del vento dell'ovest, che doveva venire ad asciugare i panni per il matrimonio.

"Sì," disse Halvor, "È giusto andato ad abbattere un po' di abeti rossi. Tra non molto sarà qui." E allora chiese loro la strada per il castello di Soria Moria. Loro

gli indicarono la giusta direzione e quando giunse davanti al castello, era così pieno di cavalli e di persone che ne brulicava. Halvor era così cencioso e lacero per aver seguito il vento dell'ovest attraverso cespugli e paludi che si fece da parte e non volle introdursi tra la folla fino all'ultimo giorno, quando la festa si sarebbe tenuta a mezzogiorno.

Così quando tutti, com'era uso e costume, brindarono alla sposa e alle giovani che stavano lì, il coppiere dovette brindare con ognuno, sia la sposa che lo sposo, cavalieri e servitori e, infine, dopo parecchio tempo, raggiunse Halvor. Lui bevve alla loro salute e poi fece scivolare nella coppa l'anello che la principessa gli aveva messo al dito quando sedevano sulla riva

dello stagno; e ordinò al coppiere di portare la coppa alla sposa da parte sua e di salutarla.

Allora la principessa si alzò da tavola e disse: "Chi è il più meritevole di avere una di noi - chi ci ha liberate dai troll o chi è seduto qui come sposo?"

Non si poteva avere che una sola opinione, pensarono tutti, e quando Halvor sentì ciò che dicevano, non ci mise molto a liberarsi degli stracci da mendicante e a prendere posto in qualità di sposo.

"Sì, è lui quello giusto, " esclamò la principessa più giovane quando posò lo sguardo su di lui; così gettò l'altro dalla finestra e celebrò le nozze con Halvor.

(1) Poiché l'esclamazione nel testo originale è un termine intraducibile, ho adattato l'espressione dell'orco che sente odore di bambini in casa propria, come ad esempio nella favola "Giacomo e il fagiolo magico" o in "Pollicino"

Peter Christian Asbjørnsen

Riguardo al significato del nome Soria Moria, su Wikipedia ho trovato questa definizione, non so quanto attendibile : È possibile che il primo nome abbia affinità con il sanscrito Surya, uno dei nomi del sole nella tradizione vedica. Moria si potrebbe comprendere alla luce del termine sanscrito Mulya, che significa acquistabile, lodevole o "essendo alla radice". Mettendo insieme questi elementi, Soria Moria si può tradurre come un regno mitico che ha radici nel sole, associabile alla mitica terra vergine di Shambhala. Come molti linguaggi di origine Indo-Europea, il norreno e il norvegese condividono molte parole con il Sanscrito. Potrebbe essere di un certo interesse, una possibile influenza, che il luogo del tempio di re Salomone sia chiamato Moriah, con il significato di qualcosa come "decretato da Dio". Secondo la tradizione è il luogo in cui Abramo fu sul punto di sacrificare Isacco. (N.d.T.)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)