The Master Thief

(MP3-15,1MB;31'28'')

THERE was once upon a time a husbandman who had three sons. He had no property to bequeath to them, and no means of putting them in the way of getting a living, and did not know what to do, so he said that they had his leave to take to anything they most fancied, and go to any place they best liked. He would gladly accompany them for some part of their way, he said, and that he did. He went with them till they came to a place where three roads met, and there each of them took his own way, and the father bade them farewell and returned to his own home again. What became of the two elder I have never been able to discover, but the youngest went both far and wide.

It came to pass, one night, as he was going through a great wood, that a terrible storm came on. It blew so hard and rained so heavily that he could scarcely keep his eyes open, and before he was aware of it he had got quite out of the track, and could neither find road nor path. But he went on, and at last he saw a light far away in the wood. Then he thought he must try and get to it, and after a long, long time he did reach it. There was a large house, and the fire was burning so brightly inside that he could tell that the people were not in bed. So he went in, and inside there was an old woman who was busy about some work.

'Good evening, mother!' said the youth.

'Good evening!' said the old woman.

'Hutetu! it is terrible weather outside to-night,' said the young fellow.

'Indeed it is,' said the old woman.

'Can I sleep here, and have shelter for the night?' asked the youth.

'It wouldn't be good for you to sleep here,' said the old hag, 'for if the people of the house come home and find you, they will kill both you and me.'

'What kind of people are they then, who dwell here?' said the youth.

'Oh! robbers, and rabble of that sort,' said the old woman; 'they stole me away when I was little, and I have had to keep house for them ever since.'

'I still think I will go to bed, all the same,' said the youth. 'No matter what happens, I'll not go out to-night in such weather as this.'

'Well, then, it will be the worse for yourself,' said the old woman.

The young man lay down in a bed which stood near, but he dared not go to sleep: and it was better that he didn't, for the robbers came, and the old woman said that a young fellow who was a stranger had come there, and she had not been able to get him to go away again.

'Did you see if he had any money?' said the robbers.

'He's not one to have money, he is a tramp! If he has a few clothes to his back, that is all.'

Then the robbers began to mutter to each other apart about what they should do with him, whether they should murder him, or what else they should do. In the meantime the boy got up and began to talk to them, and ask them if they did not want a man-servant, for he could find pleasure enough in serving them.

'Yes,' said they, 'if you have a mind to take to the trade that we follow, you may have a place here.'

'It's all the same to me what trade I follow,' said the youth, 'for when I came away from home my father gave me leave to take to any trade I fancied.'

'Have you a fancy for stealing, then?' said the robbers.

'Yes,' said the boy, for he thought that was a trade which would not take long to learn.

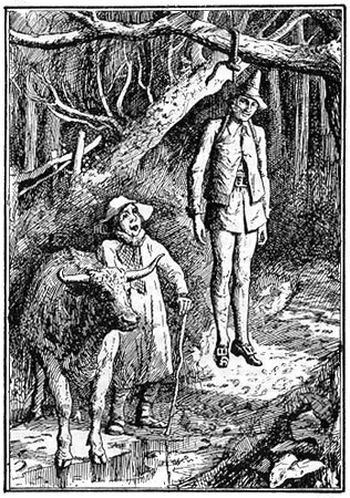

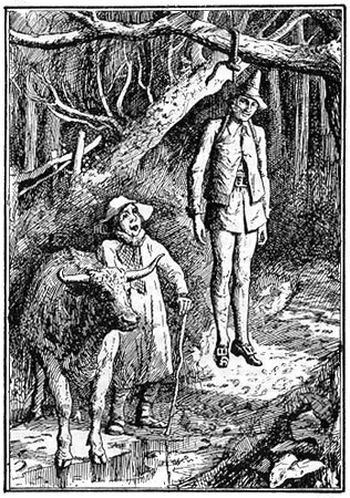

Not very far off there dwelt a man who had three oxen, one of which he was to take to the town to sell. The robbers had heard of this, so they told the youth that if he were able to steal the ox from him on the way, without his knowing, and without doing him any harm, he should have leave to be their servant-man. So the youth set off, taking with him a pretty shoe with a silver buckle that was lying about in the house. He put this in the road by which the man must go with his ox, and then went into the wood and hid himself under a bush. When the man came up he at once saw the shoe.

'That's a brave shoe,' said he. 'If I had but the fellow to it, I would carry it home with me, and then I should put my old woman into a good humour for once.'

For he had a wife who was so cross and ill-tempered that the time between the beatings she gave him was very short. But then he bethought himself that he could do nothing with one shoe if he had not the fellow to it, so he journeyed onwards and let it lie where it was. Then the youth picked up the shoe and hurried off away through the wood as fast as he was able, to get in front of the man, and then put the shoe in the road before him again.

When the man came with the ox and saw the shoe, he was quite vexed at having been so stupid as to leave the fellow to it lying where it was, instead of bringing it on with him.

'I will just run back again and fetch it now,' he said to himself, 'and then I shall take back a pair of good shoes to the old woman, and she may perhaps throw a kind word to me for once.'

So he went and searched and searched for the other shoe for a long, long time, but no shoe was to be found, and at last he was forced to go back with the one which he had.

In the meantime the youth had taken the ox and gone off with it. When the man got there and found that his ox was gone, he began to weep and wail, for he was afraid that when his old woman got to know she would be the death of him. But all at once it came into his head to go home and get the other ox, and drive it to the town, and take good care that his old wife knew nothing about it. So he did this; he went home and took the ox without his wife's knowing about it, and went on his way to the town with it. But the robbers they knew it well, because they got out their magic. So they told the youth that if he could take this ox also without the man knowing anything about it, and without doing him any hurt, he should then be on an equality with them.

'Well, that will not be a very hard thing to do,' thought the youth.

This time he took with him a rope and put it under his arms and tied himself up to a tree, which hung over the road that the man would have to take. So the man came with his ox, and when he saw the body hanging there he felt a little queer.

'What a hard lot yours must have been to make you hang yourself!' said he. 'Ah, well! you may hang there for me; I can't breathe life into you again.'

So on he went with his ox. Then the youth sprang down from the tree, ran by a short cut and got before him, and once more hung himself up on a tree in the road before the man.

'How I should like to know if you really were so sick at heart that you hanged yourself there, or if it is only a hobgoblin that's before me!' said the man. 'Ah, well! you may hang there for me, whether you are a hobgoblin or not,' and on he went with his ox.

Once more the youth did just as he had done twice already; jumped down from the tree, ran by a short cut through the wood, and again hanged himself in the very middle of the road before him.

But when the man once more saw this he said to himself, 'What a bad business this is! Can they all have been so heavy-hearted that they have all three hanged themselves? No, I can't believe that it is anything but witchcraft! But I will know the truth,' he said; 'if the two others are still hanging there it is true but if they are not it's nothing else but witchcraft.'

So he tied up his ox and ran back to see if they really were hanging there. While he was going, and looking up at every tree as he went, the youth leapt down and took his ox and went off with it. Any one may easily imagine what a fury the man fell into when he came back and saw that his ox was gone. He wept and he raged, but at last he took comfort and told himself that the best thing to do was to go home and take the third ox, without letting his wife know anything about it, and then try to sell it so well that he got a good sum of money for it. So he went home and took the third ox, and drove it off without his wife knowing anything about it. But the robbers knew all about it, and they told the youth that if he could steal this as he had stolen the two others, he should be master of the whole troop. So the youth set out and went to the wood, and when the man was coming along with the ox he began to bellow loudly, just like a great ox somewhere inside the wood. When the man heard that he was right glad, for he fancied he recognised the voice of his big bullock, and thought that now he should find both of them again. So he tied up the third, and ran away off the road to look for them in the wood. In the meantime the youth went away with the third ox. When the man returned and found that he had lost that too, he fell into such a rage that there was no bounds to it. He wept and lamented, and for many days he did not dare to go home again, for he was afraid that the old woman would slay him outright. The robbers, also, were not very well pleased at this, for they were forced to own that the youth was at the head of them all. So one day they made up their minds to set to work to do something which it was not in his power to accomplish, and they all took to the road together, and left him at home alone. When they were well out of the house, the first thing that he did was to drive the oxen out on the road, whereupon they all ran home again to the man from whom he had stolen them, and right glad was the husbandman to see them. Then he brought out all the horses the robbers had, and loaded them with the most valuable things which he could find - vessels of gold and of silver, and clothes and other magnificent things - and then he told the old woman to greet the robbers from him and thank them from him, and say that he had gone away, and that they would have a great deal of difficulty in finding him again, and with that he drove the horses out of the courtyard. After a long, long time he came to the road on which he was travelling when he came to the robbers. And when he had got very near home, and was in sight of the house where his father lived, he put on a uniform which he had found among the things he had taken from the robbers, and which was made just like a general's, and drove into the yard just as if he were a great man. Then he entered the house and asked if he could find a lodging there.

'No, indeed you can't!' said his father. 'How could I possibly be able to lodge such a great gentleman as you? It is all that I can do to find clothes and bedding for myself, and wretched they are.'

'You were always a hard man,' said the youth, 'and hard you are still if you refuse to let your own son come into your house.'

'Are you my son?' said the man.

'Do you not know me again then?' said the youth.

Then he recognised him and said, 'But what trade have you taken to that has made you such a great man in so short a time?'

'Oh, that I will tell you,' answered the youth. 'You said that I might take to anything I liked, so I apprenticed myself to some thieves and robbers, and now I have served my time and have become Master Thief.'

Now the Governor of the province lived by his father's cottage, and this Governor had such a large house and so much money that he did not even know how much it was, and he had a daughter too who was both pretty and dainty, and good and wise. So the Master Thief was determined to have her to wife, and told his father that he was to go to the Governor, and ask for his daughter for him. 'If he asks what trade I follow, you may say that I am a Master Thief,' said he.

'I think you must be crazy,' said the man, 'for you can't be in your senses if you think of anything so foolish.'

'You must go to the Governor and beg for his daughter—there is no help,' said the youth.

'But I dare not go to the Governor and say this. He is so rich and has so much wealth of all kinds,' said the man.

'There is no help for it,' said the Master Thief; 'go you must, whether you like it or not. If I can't get you to go by using good words, I will soon make you go with bad ones.'

But the man was still unwilling, so the Master Thief followed him, threatening him with a great birch stick, till he went weeping and wailing through the door to the Governor of the province.

'Now, my man, and what's amiss with you?' said the Governor.

So he told him that he had three sons who had gone away one day, and how he had given them permission to go where they chose, and take to whatsoever work they fancied. 'Now,' he said, 'the youngest of them has come home, and has threatened me till I have come to you to ask for your daughter for him, and I am to say that he is a Master Thief,' and again the man fell a-weeping and lamenting.

'Console yourself, my man,' said the Governor, laughing. 'You may tell him from me that he must first give me some proof of this. If he can steal the joint off the spit in the kitchen on Sunday, when every one of us is watching it, he shall have my daughter. Will you tell him that?'

The man did tell him, and the youth thought it would be easy enough to do it. So he set himself to work to catch three hares alive, put them in a bag, clad himself in some old rags so that he looked so poor and wretched that it was quite pitiable to see him, and in this guise on Sunday forenoon he sneaked into the passage with his bag, like any beggar boy. The Governor himself and everyone in the house was in the kitchen, keeping watch over the joint. While they were doing this the youth let one of the hares slip out of his bag, and off it set and began to run round the yard.

'Just look at that hare,' said the people in the kitchen, and wanted to go out and catch it.

The Governor saw it too, but said, 'Oh, let it go! it's no use to think of catching a hare when it's running away.'

It was not long before the youth let another hare out, and the people in the kitchen saw this too, and thought that it was the same. So again they wanted to go out and catch it, but the Governor again told them that it was of no use to try.

Very soon afterwards, however, the youth let slip the third hare, and it set off and ran round and round the courtyard. The people in the kitchen saw this too, and believed that it was still the same hare that was running about, so they wanted to go out and catch it.

'It's a remarkably fine hare!' said the Governor. 'Come and let us see if we can get hold of it.' So out he went, and the others with him, and away went the hare, and they after it, in real earnest.

In the meantime, however, the Master Thief took the joint and ran off with it, and whether the Governor got any roast meat for his dinner that day I know not, but I know that he had no roast hare, though he chased it till he was both hot and tired. At noon came the Priest, and when the Governor had told him of the trick played by the Master Thief there was no end to the ridicule he cast on the Governor.

'For my part,' said the Priest, 'I can't imagine myself being made a fool of by such a fellow as that!'

'Well, I advise you to be careful,' said the Governor, 'for he may be with you before you are at all aware.'

But the Priest repeated what he had said, and mocked the Governor for having allowed himself to be made such a fool of.

Later in the afternoon the Master Thief came and wanted to have the Governor's daughter as he had promised.

'You must first give some more samples of your skill,' said the Governor, trying to speak him fair, 'for what you did to-day was no such very great thing after all. Couldn't you play off a really good trick on the Priest? for he is sitting inside there and calling me a fool for having let myself be taken in by such a fellow as you.'

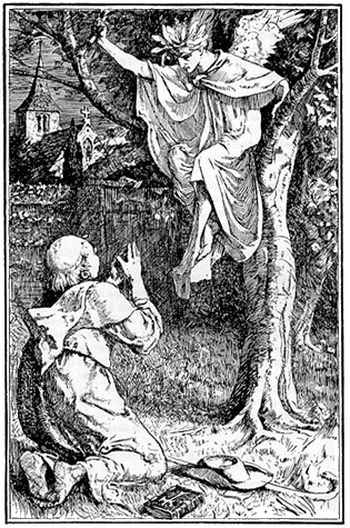

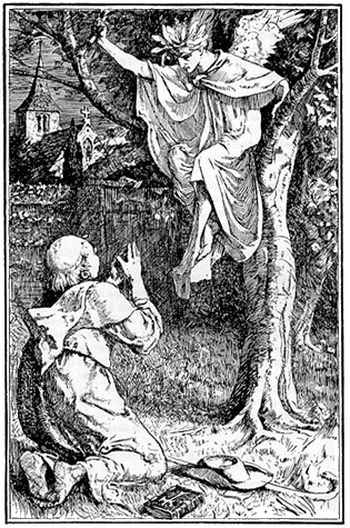

'Well, it wouldn't be very hard to do that,' said the Master Thief. So he dressed himself up like a bird, and threw a great white sheet over himself; broke off a goose's wings, and set them on his back; and in this attire climbed into a great maple tree which stood in the Priest's garden. So when the Priest returned home in the evening the youth began to cry, 'Father Lawrence! Father Lawrence! 'for the Priest was called Father Lawrence.

'Who is calling me?' said the Priest.

'I am an angel sent to announce to thee that because of thy piety thou shalt be taken away alive into heaven,' said the Master Thief. 'Wilt thou hold thyself in readiness to travel away next Monday night? for then will I come and fetch thee, and bear thee away with me in a sack, and thou must lay all thy gold and silver, and whatsoever thou may 'st possess of this world's wealth, in a heap in thy best parlour.'

So Father Lawrence fell down on his knees before the angel and thanked him, and the following Sunday he preached a farewell sermon, and gave out that an angel had come down into the large maple tree in his garden, and had announced to him that, because of his righteousness, he should be taken up alive into heaven, and as he thus preached and told them this everyone in the church, old or young, wept.

On Monday night the Master Thief once more came as an angel, and before the Priest was put into the sack he fell on his knees and thanked him; but no sooner was the Priest safely inside it than the Master Thief began to drag him away over stocks and stones.

'Oh! oh! 'cried the Priest in the sack. 'Where are you taking me?'

'This is the way to heaven. The way to heaven is not an easy one,' said the Master Thief, and dragged him along till he all but killed him.

At last he flung him into the Governor's goose-house, and the geese began to hiss and peck at him, till he felt more dead than alive.

'Oh! oh! oh! Where am I now?' asked the Priest.

'Now you are in Purgatory,' said the Master Thief, and off he went and took the gold and the silver and all the precious things which the Priest had laid together in his best parlour.

Next morning, when the goose-girl came to let out the geese, she heard the Priest bemoaning himself as he lay in the sack in the goose-house.

'Oh, heavens! who is that, and what ails you?' said she. 'Oh,' said the Priest, 'if you are an angel from heaven do let me out and let me go back to earth again, for no place was ever so bad as this - the little fiends nip me so with their tongs.'

'I am no angel,' said the girl, and helped the Priest out of the sack. 'I only look after the Governor's geese, that's what I do, and they are the little fiends which have pinched your reverence.'

'This is the Master Thief's doing! Oh, my gold and my silver and my best clothes!' shrieked the Priest, and, wild with rage, he ran home so fast that the goose-girl thought he had suddenly gone mad.

When the Governor learnt what had happened to the Priest he laughed till he nearly killed himself, but when the Master Thief came and wanted to have his daughter according to promise, he once more gave him nothing but fine words, and said, 'You must give me one more proof of your skill, so that I can really judge of your worth. I have twelve horses in my stable, and I will put twelve stable boys in it, one on each horse. If you are clever enough to steal the horses from under them, I will see what I can do for you.'

'What you set me to do can be done,' said the Master Thief, 'but am I certain to get your daughter when it is?'

'Yes; if you can do that I will do my best for you,' said the Governor.

So the Master Thief went to a shop, and bought enough brandy to fill two pocket flasks, and he put a sleeping drink into one of these, but into the other he poured brandy only. Then he engaged eleven men to lie that night in hiding behind the Governor's stable. After this, by fair words and good payment, he borrowed a ragged gown and a jerkin from an aged woman, and then, with a staff in his hand and a poke on his back, he hobbled off as evening came on towards the Governor's stable. The stable boys were just watering the horses for the night, and it was quite as much as they could do to attend to that.

'What on earth do you want here?' said one of them to the old woman.

'Oh dear! oh dear! How cold it is!' she said, sobbing, and shivering with cold. 'Oh dear! oh dear! it's cold enough to freeze a poor old body to death!' and she shivered and shook again, and said, 'For heaven's sake give me leave to stay here and sit just inside the stable door.'

'You will get nothing of the kind! Be off this moment! If the Governor were to catch sight of you here, he would lead us a pretty dance,' said one.

'Oh! what a poor helpless old creature!' said another, who felt sorry for her. 'That poor old woman can do no harm to anyone. She may sit there and welcome.'

The rest of them thought that she ought not to stay, but while they were disputing about this and looking after the horses, she crept farther and farther into the stable, and at last sat down behind the door, and when once she was inside no one took any more notice of her.

As the night wore on the stable boys found it rather cold work to sit still on horseback.

'Hutetu! But it is fearfully cold!' said one, and began to beat his arms backwards and forwards across his breast.

'Yes, I am so cold that my teeth are chattering,' said another.

'If one had but a little tobacco,' said a third.

Well, one of them had a little, so they shared it among them, though there was very little for each man, but they chewed it. This was some help to them, but very soon they were just as cold as before.

'Hutetu!' said one of them, shivering again.

'Hutetu!' said the old woman, gnashing her teeth together till they chattered inside her mouth; and then she got out the flask which contained nothing but brandy, and her hands trembled so that she shook the bottle about, and when she drank it made a great gulp in her throat.

'What is that you have in your flask, old woman?' asked one of the stable boys.

'Oh, it's only a little drop of brandy, your honour,' she said.

'Brandy! What! Let me have a drop! Let me have a drop!' screamed all the twelve at once.

'Oh, but what I have is so little,' whimpered the old woman. 'It will not even wet your mouths.'

But they were determined to have it, and there was nothing to be done but give it; so she took out the flask with the sleeping drink and put it to the lips of the first of them; and now she shook no more, but guided the flask so that each of them got just as much as he ought, and the twelfth had not done drinking before the first was already sitting snoring. Then the Master Thief flung off his beggar's rags, and took one stable boy after the other and gently set him astride on the partitions which divided the stalls, and then he called his eleven men who were waiting outside, and they rode off with the Governor's horses.

In the morning when the Governor came to look after his stable boys they were just beginning to come to again. They were driving their spurs into the partition till the splinters flew about, and some of the boys fell off, and some still hung on and sat looking like fools. 'Ah, well,' said the Governor, 'it is easy to see who has been here; but what a worthless set of fellows you must be to sit here and let the Master Thief steal the horses from under you!' And they all got a beating for not having kept watch better.

Later in the day the Master Thief came and related what he had done, and wanted to have the Governor's daughter as had been promised. But the Governor gave him a hundred dollars, and said that he must do something that was better still.

'Do you think you can steal my horse from under me when I am out riding on it?' said he. 'Well, it might be done,' said the Master Thief, 'if I were absolutely certain that I should get your daughter.'

So the Governor said that he would see what he could do, and then he said that on a certain day he would ride out to a great common where they drilled the soldiers.

So the Master Thief immediately got hold of an old worn-out mare, and set himself to work to make a collar for it of green withies and branches of broom; bought a shabby old cart and a great cask, and then he told a poor old beggar woman that he would give her ten dollars if she would get into the cask and keep her mouth wide-open beneath the tap-hole, into which he was going to stick his finger. No harm should happen to her, he said; she should only be driven about a little, and if he took his finger out more than once, she should have ten dollars more. Then he dressed himself in rags, dyed himself with soot, and put on a wig and a great beard of goat's hair, so that it was impossible to recognise him, and went to the parade ground, where the Governor had already been riding about a long time.

When the Master Thief got there the mare went along so slowly and quietly that the cart hardly seemed to move from the spot. The mare pulled it a little forward, and then a little back, and then it stopped quite short. Then the mare pulled a little forward again, and it moved with such difficulty that the Governor had not the least idea that this was the Master Thief. He rode straight up to him, and asked if he had seen anyone hiding anywhere about in a wood that was close by.

'No,' said the man, 'that have I not.'

'Hark you,' said the Governor. 'If you will ride into that wood, and search it carefully to see if you can light upon a fellow who is hiding in there, you shall have the loan of my horse and a good present of money for your trouble.'

'I am not sure that I can do it,' said the man, 'for I have to go to a wedding with this cask of mead which I have been to fetch, and the tap has fallen out on the way, so now I have to keep my finger in the tap-hole as I drive.'

'Oh, just ride off,' said the Governor, 'and I will look after the cask and the horse too.'

So the man said that if he would do that he would go, but he begged the Governor to be very careful to put his finger into the tap-hole the moment he took his out.

So the Governor said that he would do his very best, and the Master Thief got on the Governor's horse.

But time passed, and it grew later and later, and still the man did not come back, and at last the Governor grew so weary of keeping his finger in the tap-hole that he took it out.

'Now I shall have ten dollars more!' cried the old woman inside the cask; so he soon saw what kind of mead it was, and set out homewards. When he had gone a very little way he met his servant bringing him the horse, for the Master Thief had already taken it home.

The following day he went to the Governor and wanted to have his daughter according to promise. But the Governor again put him off with fine words, and only gave him three hundred dollars, saying that he must do one more masterpiece of skill, and if he were but able to do that he should have her.

Well, the Master Thief thought he might if he could hear what it was.

'Do you think you can steal the sheet off our bed, and my wife's night-gown?' said the Governor.

'That is by no means impossible,' said the Master Thief. 'I only wish I could get your daughter as easily.'

So late at night the Master Thief went and cut down a thief who was hanging on the gallows, laid him on his own shoulders, and took him away with him. Then he got hold of a long ladder, set it up against the Governor's bedroom window, and climbed up and moved the dead man's head up and down, just as if he were some one who was standing outside and peeping in.

'There's the Master Thief, mother!' said the Governor, nudging his wife. 'Now I'll just shoot him, that I will!'

So he took up a rifle which he had laid at his bedside.

'Oh no, you must not do that,' said his wife; 'you yourself arranged that he was to come here.'

'Yes, mother, I will shoot him,' said he, and lay there aiming, and then aiming again, for no sooner was the head up and he caught sight of it than it was gone again. At last he got a chance and fired, and the dead body fell with a loud thud to the ground, and down went the Master Thief too, as fast as he could.

'Well,' said the Governor, 'I certainly am the chief man about here, but people soon begin to talk, and it would be very unpleasant if they were to see this dead body; the best thing that I can do is to go out and bury him.'

'Just do what you think best, father,' said his wife.

So the Governor got up and went downstairs, and as soon as he had gone out through the door, the Master Thief stole in and went straight upstairs to the woman.

'Well, father dear,' said she, for she thought it was her husband. 'Have you got done already?'

'Oh yes, I only put him into a hole,' said he, 'and raked a little earth over him; that's all I have been able to do to-night, for it is fearful weather outside. I will bury him better afterwards, but just let me have the sheet to wipe myself with, for he was bleeding, and I have got covered with blood with carrying him.'

So she gave him the sheet.

'You will have to let me have your night-gown too,' he said, 'for I begin to see that the sheet won't be enough.'

Then she gave him her night-gown, but just then it came into his head that he had forgotten to lock the door, and he was forced to go downstairs and do it before he could lie down in bed again. So off he went with the sheet, and the night-gown too.

An hour later the real Governor returned.

'Well, what a time it has taken to lock the house door, father!' said his wife, 'and what have you done with the sheet and the night-gown?'

'What do you mean?' asked the Governor.

'Oh, I am asking you what you have done with the night-gown and sheet that you got to wipe the blood off yourself with,' said she.

'Good heavens!' said the Governor, 'has he actually got the better of me again?'

When day came the Master Thief came too, and wanted to have the Governor's daughter as had been promised, and the Governor dared do no otherwise than give her to him, and much money besides, for he feared that if he did not the Master Thief might steal the very eyes out of his head, and that he himself would be ill spoken of by all men. The Master Thief lived well and happily from that time forth, and whether he ever stole any more or not I cannot tell you, but if he did it was but for pastime.

From P. C. Asbjørnsen.

Il Capo dei Ladri

C’ERA una volta un contadino che aveva tre figli. Non aveva possedimenti da lasciare loro in eredità, né modo di consentire loro di farsi una posizione nella vita, e non sapeva che cosa fare, così disse loro che avevano il suo consenso per fare qualsiasi cosa piacesse e di andare in qualunque posto volessero. Li avrebbe accompagnati volentieri per un tratto di strada, disse, e così fece. Andò con loro finché giunsero in un posto in cui tre strade convergevano e lì ciascuno di loro prese la propria strada; il padre disse loro addio e tornò di nuovo a casa. Che cosa fu dei due fratelli maggiori non sono in grado di rivelarvelo, ma il più giovane andò in lungo e in largo.

Successe che una notte, mentre stava attraversando una grande foresta, si scatenò una terribile tempesta. Il vento soffiava così forte e la pioggia scrosciava con tale violenza che riusciva a malapena a tenere gli occhi aperti, e prima di rendersene conto perse l’orientamento senza poter trovare né una strada né un sentiero. Tuttavia proseguì e infine vide una luce in lontananza nella foresta. Allora pensò che doveva tentare e diriger visi, e dopo molto, molto tempo, la raggiunse. C’era una grande casa e il fuoco bruciava con tale intensità all’interno che si disse che gli abitanti non dovessero essere ancora a letto. Così entrò e dentro c’era una vecchia occupata con un lavoro.

”Buonasera, madre!” disse il giovane.

”Buonasera!” disse la vecchia.

”Eh, già.” disse la vecchia.

”Posso dormire qui e avere ricovero per la notte?” chiese il giovane.

”Non ti converrebbe dormire qui,” disse la megera, “perché se gli abitanti della casa rientrassero e ti trovassero qui, ucciderebbero te e me.”

”Che razza di gente è, allora, quella che abita qui?” disse il giovane.

”Oh, ladri, e gentaglia del genere,” disse la vecchia; “mi hanno rapita quando ero piccola e ho dovuto badare alla casa per loro da allora.”

”Penso che andrò a letto ugualmente,” disse il giovane. “No importa ciò che accadrà, non uscirò stanotte con un tempo simile.”

”Beh, allora peggio per te.” Disse la vecchia.

Il giovane si sdraiò su un letto che si trovava lì vicino, ma non osava addormentarsi; e fu un bene che non l’avesse fatto perché tornarono i ladri e la vecchia disse che un giovane straniero era venuto lì e lei non era stata capace di mandarlo via di nuovo.

”Hai visto se aveva del denaro?” dissero i ladri.

”Non è tipo da avere denaro, è un vagabondo! Se ha addosso un po’ dii vestiti, è già tanto.”

Allora i ladri si misero a bisbigliare l’uno con l’altro in disparte su ciò che avrebbero dovuto fare di lui, se avessero dovuto ucciderlo o fare qualsiasi altra cosa. Nel frattempo il ragazzo si sollevò e cominciò a parlare con loro, e chiese se non volessero un servitore, perché gli sarebbe assai piaciuto mettersi al loro servizio.

”E sia,” dissero, “se hai intenzione di intraprendere il nostro mestiere, può restare qui.””

”Mi va bene qualsiasi mestiere da intraprendere,” disse il giovane “perché quando me ne sono andato di casa, mio padre il permesso di fare qualsiasi cosa mi piacesse.”

”Allora ti piacerebbe il furto?” dissero i ladri.

”Sì. disse il ragazzo, perché pensava fosse un lavoro che non ci volesse molto a imparare.

Non molto lontano da lì abitava un uomo che aveva tre buoi, uno dei quali doveva portare a vendere in città. I ladri ne erano venuti a sapere, così dissero al giovane se fosse stato capace di rubargli il bue lungo la strada, senza che lui se ne accorgesse e gli facesse alcun male, lo avrebbero preso come servitore. Così il giovane si avviò, prendendo con sé una bella scarpa dalla fibbia d’argento che si trovava lì in casa. La mise sulla strada per la quale doveva passare l’uomo con il bue e poi andò nel bosco e si nascose sotto un cespuglio. Quando l’uomo arrivò, vide subito la scarpa.

”Questa sì che è un’ottima scarpa,” disse. “Se avesse la sua compagna, la porterei a casa con me e una volta tanto potrei mettere di buonumore la mia vecchia moglie.”

Perché aveva una moglie che era così bisbetica e irascibile che passava solo breve tempo tra una bastonatura e l’altra che gli dava. Ma meditò fra sé che non se ne sarebbe fatto nulla di una scarpa se non avesse trovata la compagna, così proseguì il viaggio e la lasciò li dov’era. Allora il giovane prese la scarpa e corse attraverso la foresta più veloce che poté, per precedere l’uomo, e poi gli mise di nuovo la scarpa davanti sulla strada.

Quando l’uomo giunse con il bue e vide la scarpa, si irritò per essere stato così stupido da lasciare la compagna dove era, invece di prenderla con sé.

”Tornerò indietro di corsa e la prenderò adesso,” disse tra sé, “e allora riporterò un buon paio di scarpe alla mia vecchia, e può darsi che per una volta mi dica una parola gentile.”

Così andò e cercò e ricercò a lungo l’altra scarpa, ma non la trovò e alla fine fu costretto a tornare indietro con l’unica che aveva.

Nel medesimo tempo il giovane aveva preso il bue e se n’era andato via con esso. Quando l’uomo tornò e scopri che il bue non c’era più, cominciò a piangere e a lamentarsi, perché aveva paura che quando la sua vecchia lo avesse saputo, l’avrebbe voluto morto. Ma all’improvviso gli venne in mente di andare a casa e prendere un altro bue, portarlo in città e far bene attenzione che la sua vecchia moglie non ne sapesse nulla. Così lo fece; andò a casa e prese il bue senza che sua moglie se ne accorgesse, e riprese la via per la città con esso. Ma i ladri lo seppero, perché avevano i loro sistemi. Così dissero al giovane che, se avesse preso anche questo bue senza che l’uomo se ne accorgesse, e senza che gli facesse alcun male, sarebbe divenuto un loro pari.

”Beh, non mi sembra molto difficile da fare.” pensò il giovane.

Stavolta prese con sé una corda, se la passò sotto le braccia e si appese a un albero che si trovava lungo la strada che l’uomo avrebbe percorso. Così arrivò l’uomo con il bue e quando vide lì il corpo che penzolava, gli parve un po’ strano.

”Quanta forza devi aver avuto per impiccarti da solo!” disse. “Ah, beh! Per me puoi restare a penzoloni là: non posso soffiare di nuovo dentro di te la vita.”

Così se ne andò col suo bue. Allora il giovane balzò giù dall’albero, prese una scorciatoia e lo precedette, e ancora una volta si appese a un albero sulla strada dell’uomo.

”Come mi piacerebbe sapere se veramente sei stato così addolorato da impiccarti qui o se c’è solo uno spauracchio davanti a me!” disse l’uomo. “Ah, beh! Per me puoi restare appeso qui, che tu sia o no uno spauracchio.” E proseguì con il suo bue.

Ancora una volta il giovane fece ciò che aveva fatto le due volte precedenti; saltò giù dall’albero, percorse una scorciatoia attraverso la foresta e di nuovo si appese nel bel mezzo della strada davanti a lui.

Ma quando l’uomo vide di nuovo ciò, disse a se stesso. “Ma che brutto affare! Possono essere stati così tristi da impiccarsi tutti e tre? No, non credo sia altro che una stregoneria! Ma scoprirò la verità,” disse; “se gli altri due stanno ancora penzolando, è la verità, ma se non ci sono, allora non è altro che stregoneria.”

Così legò il bue e corse indietro per vedere se davvero fossero appesi la. Mentre lui andava e guardava ogni albero che incontrava, il ragazzo saltò giù, prese il bue e andò via con esso. Si può facilmente immaginare la rabbia dell’uomo quando tornò indietro e vide che il bue era sparito. Pianse e si infuriò, ma alla fine si consolò e disse a se stesso che la cosa migliore era andare a casa e prendere il terzo bue, senza permettere che sua moglie ne sapesse qualcosa, e poi venderlo così bene da ricavare un’eccellente quantità di monete. Così andò a casa e prese il terzo bue, e lo condusse fuori senza che sua moglie ne sapesse niente. Ma i ladri sapevano tutto ciò e dissero al giovane che se avesse rubato questo come aveva rubato gli altri due, sarebbe divenuto il capo dell’intera brigata. Così il ragazzo partì e andò nella foresta, e quando l’uomo si stava avvicinando con il bue, cominciò a muggire sonoramente, proprio come un grosso bue da qualche parte nella foresta. Quando l’uomo sentì ne fu molto felice, perché gli parve di riconoscere la voce del suo grosso manzo e pensò che adesso li avrebbe ritrovati di nuovo entrambi. Così legò il terzo e corse lungo la strada nella foresta in cerca di essi. Nello stesso tempo il giovane se ne andò con il terzo bue. Quando l’uomo ritornò e scoprì di aver perso anche quello, montò tanto in collera che non si può dire quanto. Pianse e si lamentò, e per molti giorni non osò tornare di nuovo a casa, perché aveva paura che la sua vecchia lo avrebbe ammazzato all’istante. Anche i ladri non erano molto soddisfatti perché erano obbligati a riconoscere che il giovane fosse il capo di tutti loro. Così un giorno decisero di fare qualcosa che lui non fosse in grado di portare a termine, e presero la strada, tutti insieme, lasciandolo solo a casa. Quando se ne furono andati di casa, la prima cosa che fece fu condurre in buoi sulla strada, dopodiché corsero tutti verso casa dall’uomo al quale li aveva rubati, ed è facile immaginare quanto fosse contento di rivederli. Poi prese tutti i cavalli che i ladri possedevano e li caricò con le cose più preziose che riuscì a trovare – recipienti d’oro e d’argento, e abiti e altre magnifiche cose – e poi disse alla vecchia di salutare e di ringraziare per lui i ladri poi disse che se ne sarebbe andato via e che si sarebbero trovati in gran difficoltà a trovarlo di nuovo; e con ciò condusse i cavalli fuori dal cortile. Dopo molto, molto tempo arrivò sulla strada sulla quale stava viaggiando quando era giunto dai ladri. E quando fu vicinissimo a casa e fu in vista della dimora in cui viveva il padre, prese un’uniforme che aveva trovato tra le cose che aveva sottratto ai ladri, e abbigliato proprio come un generale, entrò bel cortile proprio come fosse un grand’uomo. Poi entrò in casa e chiese di poter essere ospitato lì.

”no, non posso proprio!” disse il padre. “Com’è possibile che io sia in grado di ospitare un tale gentiluomo come voi? Tutto ciò che posso fare è trovare abiti e un letto per me stesso, miserevoli come sono.”

”Sei sempre stato un uomo duro,” disse il giovane “ e duro sei se ancora rifiuterai di accogliere in casa tua il tuo proprio figlio.”

”Tu sei mio figlio?” disse l’uomo.

”Dunque non mi riconosci?” disse il giovane.

Allora lo riconobbe e disse: “Che cosa hai fatto per diventare un grand’uomo simile in così breve tempo?”

”Oh, te lo dirò,” rispose il giovane. “Hai detto che avrei potuto fare qualsiasi cosa avessi voluto, così ho fatto pratica con un po’ di ladri e di briganti, e adesso ho terminato e sono diventato il Capo dei Ladri.”

Il Governatore della provincia viveva vicino alla casetta di suo padre, e questo Governatore aveva una casa così grande e così tanto denaro che persino lui non sapeva quanto, e aveva anche una figlia graziosa e delicata, buona e saggia. Così il Capo dei Ladri decise di averla in moglie, e disse a suo padre che doveva andare dal Governatore e chiedergli sua figlia per lui. “Se chiede che lavoro io faccia, puoi dirgli che sono il Capo dei Ladri,” disse.

”Io penso che tu sia pazzo,” disse l’uomo, “ perché non sei in possesso delle tue facoltà se pensi ad una cosa tanto folle.”

Devi andare dal Governatore e implorare la mano di sua figlia – non c’è niente da fare,” disse il giovane.

”Ma io non oso andare dal Governatore e dirgli ciò. È così ricco e ha così tanti beni di ogni genere,” disse l’uomo.

”Non c’è niente da fare,” disse il Capo dei Ladri; “devi andare, che ti piaccia o no. Se non ti ci posso mandare con le buone, ti ci manderò con le cattive.”

Ma l’uomo era ancora riluttante, così il Capo dei Ladri lo inseguì, minacciandolo con un grande randello di betulla, finché piangendo e lamentandosi oltrepassò la porta del Governatore della provincia.

”Adesso, buon uomo, che cosa non ti garba?” disse il Governatore.

Così gli disse che aveva tre figli che un giorno se n’erano andati, e come avesse dato loro il permesso di andare dove volessero e fare qualunque cosa li aggradasse. “Ora,” disse “il più giovane di loro è tornato a casa, e mi ha minacciato finché non sono venuto da te a chiedere per lui la mano di tua figlia, e devo dirti che lui è il Capo dei Ladri,” e di nuovo l’uomo si abbandonò a pianti e a lamenti.

”Consolati, buon’uomo,” disse il Governatore, ridendo. “Puoi dirgli da parte mia che prima deve darmene una prova. Se domenica può rubare l’arrosto dallo spiedo mentre ognuno di noi sta guardando, avrà mia figlia. Glielo dirai?”

L’uomo glielo disse, e il giovane pensò che sarebbe stato abbastanza facile farlo. Così si mise all’opera per acchiappare tre lepri vive, le mise in un sacco, si rivestì di vecchi stracci che lo fecero sembrare così povero e miserabile che quasi si compiangeva da solo, in così conciato di domenica, prima di mezzogiorno, s’intrufolò in un andito con il suo sacco, come un giovane mendicante. Il Governatore in persona e ogni altra persona della casa erano in cucina, a tenere d’occhio l’arrosto. Mentre erano intenti a ciò, il giovane tirò fuori dal sacco una delle lepri, e la lasciò andare e correre intorno al cortile.

”Guardate quella lepre,” dissero le persone in cucina, e volevano uscire a catturarla.

Anche il Governatore guardò, ma disse: “Oh! Lasciate perdere! È inutile pensare di acchiappare una lepre mentre corre.”

Non passò molto tempo che il giovane liberò un’altra lepre, e la gente in cucina vide anche questa e pensò fosse la stessa. Di nuovo volevano uscire a prenderla, ma il Governatore di nuovo disse loro che era inutile tentare.

Ben poco tempo dopo, tuttavia, il giovane lascio scappare la terza lepre ed essa balzò fuori e corse in lungo e in largo per il cortile, le persone in cucina videro anche questo e credettero fosse sempre la medesima lepre che correva lì intorno, così vollero uscire ad acchiapparla.

”È una lepre straordinariamente abile!” disse il Governatore. “Andiamo e vediamo se possiamo prenderla.” Così uscì, egli altri con lui, la lepre avanti e loro dietro, con grande zelo.

Nel frattempo, comunque, Il Capo dei Ladri prese l’arrosto e scappò con esso, e dove il Governatore abbia trovato dell’arrosto per il proprio pranzo quel giorno io non los o, ma so che non ebbe certo arrosto di lepre, sebbene le avesse dato la caccia finché fu tanto accaldato quanto stanco. A mezzogiorno venne il Prete, e quando il Governatore gli disse del tiro giocatogli dal Capo dei Ladri, egli non la finiva di canzonare il Governatore.

”Dal canto mio,” disse il Prete, “non posso immaginare di farmi prendere in giro da un tipo simile!”

”Be, ti consiglio di stare attento,” disse il Governatore, “perché potrebbe essere da te prima che te ne accorga.”

Ma il Prete ripeté ciò che aveva detto e derise il Governatore per essersi lasciato lasciato raggirare in quel modo.

Più tardi nel pomeriggio il Capo dei Ladri venne e reclamò la figlia del Governatore come gli era stato promesso.

”Prima dovrai darmi altre prove della tua abilità,” disse il Governatore, tentando di parlargli in modo convincente, “perché ciò che hai fatto oggi dopotutto non è un granché. Giocheresti un vero buon tiro al Prete? Perché lui era qui dentro e mi ha chiamato folle per essermi lasciato gabbare da un tipo come te.”

”Beh, non dovrebbe essere molto difficile farlo,” disse il Capo dei Ladri. Così si travestì da uccello, e si mise addosso un grande lenzuolo bianco; prese le ali a un’oca e se le fissò sul dorso; così conciato si arrampicò su un grande acero che era nel giardino del Prete. Così quando il Prete tornò a casa la sera, il giovane cominciò a gridare, “Padre Lorenzo! Padre Lorenzo!” perché il Prete si chiamava Padre Lorenzo.

”Chi mi sta chiamando?” disse il Prete.

”Sono un angelo mandato ad annunciarti che, grazie alla tua devozione, sarai assunto in cielo da vivo,” disse il Capo dei Ladri. “Sarai pronto con sollecitudine per il viaggio il prossimo lunedì notte? Perché io ti verrò a prendere allora e ti porterò via con me in un sacco, ma tu dovrai deporre tutto l’oro e l’argento, e qualsiasi altro bene in tuo possesso, in un mucchio nel salotto migliore.”

Così Padre Lorenzo cadde in ginocchio dinnanzi all’angelo e lo ringraziò; la domenica successiva pronunciò un sermone di addio e raccontò che un angelo era sceso sul grande acero in giardino e gli aveva annunciato che, in virtù della propria rettitudine, sarebbe stato assunto in cielo da vivo, e come ebbe detto e predicato ciò, ognuno in chiesa, vecchio o giovane, pianse.

Il lunedì notte il Capo dei Ladri si presentò ancora una volta sottoforma di angelo e, prima di essere messo nel sacco, il Prete cadde sulle ginocchia e lo ringraziò; ma appena il Prete fu dentro il sacco al sicuro, il Capo dei ladri cominciò a trascinarlo su sporgenze e pietre.

”Oh! Oh!” gridava il Prete nel sacco. “Dove mi stai portando?”

”Questa è la strada per il paradiso. La strada per il paradiso non è confortevole,” disse il Capo dei Ladri, e lo trascinò finché l’ebbe quasi ucciso.

Infine lo scaraventò nel recinto delle oche del Governatore, e le oche cominciarono a soffiare e a beccarlo, finché si sentì più morto che vivo.

”Oh! Oh! Oh! Adesso dove sono?” chiese il Prete.

”Ora sei in purgatorio,” disse Il Capo dei Ladri, e se ne andò, portando via tutto l’oro e l’argento e tutti gli oggetti preziosi che il Prete aveva messo insieme nel salotto buono.

Il mattino seguente, quando la guardiana delle oche venne a tirarle fuori, sentì il Prete compiangersi mentre si trovava nel sacco nel recinto delle oche.

”Santo cielo! Chi siete, e che cosa vi affligge?” disse la ragazza.

Il Prete disse: “Se sei un angelo del cielo, fammi uscire e lasciami tornare sulla terra, perché nessun posto è mai stato peggio di questo – i diavoletti mi pizzicano con le loro tenaglie.” “Non sono un angelo,” disse la ragazza, aiutando il Prete a uscire dal sacco. “Io devo solo guardare le oche del Governatore, come faccio, e sono esse i diavoletti che vi hanno pizzicato, reverendo.”

”Questa è opera del Capo dei Ladri! Oh, il mio oro, il mio argento, i miei vestiti migliori!” strillò il Prete e, folle di rabbia, corse a casa così in fretta che la guardiana di oche pensò fosse impazzito all’improvviso.

Quando il Governatore seppe che cosa era accaduto al Prete, rise tanto che quasi ne morì, ma quando il Capo dei Ladri venne e volle avere sua figlia secondo la promessa, ancora una volta non pronunciò che belle parole e disse, “Devi darmi ancora una prova della tua abilità, affinché io possa davvero giudicare il tuo valore. Nella mia stalla ho dodici cavalli, e ci metterò dodici garzoni di stalla, uno per ogni cavallo. Se sarai così abile da sottrarre loro i cavalli, vedrò che cosa posso fare per te.”

“Ciò che mi dici si può fare,” disse il Capo dei Ladri, “ma sono sicuro di avere tua figlia quando sarà?”

”Oh, sì; se lo farai, io farò del mio meglio per te,” disse il Governatore.

Così il Capo dei Ladri andò in una bottega e comprò abbastanza acquavite da riempire due fiaschette, e in una mise del sonnifero, nell’altra solo l’acquavite. Poi assoldò undici uomini perché quella notte si coricassero di nascosto dietro la stalla del Governatore. Dopo di ciò, con belle parole e denaro sonante, prese in prestito una veste sbrindellata e un giubbetto da un’anziana donna, poi, con un bastone in mano e una sacca sulle spalle, verso sera si mosse zoppicando verso la stalla del Governatore. I garzoni di stalla stavano proprio abbeverando i cavalli per la notte, ed erano del tutto occupati ad accudirli.

”Che diamine vuoi qui?” disse uno di loro alla vecchia.

”Oh, caro! Oh, caro! Quant’è freddo!” disse, singhiozzando e tremando per il freddo.. “Oh, caro! Oh, caro! È così freddo da uccidere un povero, vecchio corpo!” e tremò e si scrollò di nuovo, poi disse, “Per amor di Dio lasciami stare qui a sedere appena dentro la porta della stalla.”

”Non farai niente del genere! Vattene subito! Se il Governatore si accorgesse che sei qui, ci farebbe ballare per benino,” disse uno.

”Oh! Povera vecchia indifesa!” disse un altro, che aveva pena di lei. “Quella povera vecchia non può far male a nessuno. Lasciamo stare qui e benaccolta.”

Gli altri ritenevano che non dovesse restare, ma mentre litigavano su ciò e gettavano un’occhiata ai cavalli, lei scivolò più lontano nella stalla e infine sedette dietro la porta, e una volta che fu dentro nessuno si curò più di lei.

Quando sopraggiunse la notte, i garzoni di stalla si resero conto che faceva piuttosto freddo a stare in groppa ai cavalli.

”Brrrr! Fa un freddo terribile!” disse uno, e cominciò a battere le braccia avanti e indietro sul petto.

”Oh, sì, sono così intirizzito che batto i denti,” disse un altro.

”Se qualcuno avesse un po’ di tabacco,” disse un terzo.

Beh, uno di loro ne aveva un po’, così se lo divisero, sebbene fosse assai poco per ciascuno, e lo masticarono. Ciò li aiutò abbastanza, ma assai presto ebbero di nuovo freddo come prima.

”Brrrr!” disse uno di loro, rabbrividendo di nuovo.

”Brrrr!” disse la vecchia, digrignando i denti finché le sbatterono dentro la bocca; poi tirò fuori la fiaschetta che conteneva solo acquavite e le sue mani tremavano tanto che la fiaschetta si scuoteva tutta e quando bevve fece un gran gorgoglio in gola.

”Vecchia, che cos’hai in quella fiaschetta?” chiese uno dei garzoni di stalla.

”Oh, è solo un goccetto di acquavite, vostro onore,” disse.

”Acquavite! Che? Dammene una goccia! Dammene una goccia!” gridarono subito tutti e dodici.

”Oh, ma ne ho così poca,” piagnucolò la vecchia. “Non bagnerà le vostre bocche.”

Essi però erano decisi ad averla, e non ci fu altro da fare che darla loro; tirò fuori la fiaschetta con il sonnifero e la poggiò sulle labbra del primo di loro; e adesso non tremava più, ma maneggiò la fiaschetta così che ciascuno di essi ebbe ciò che gli serviva, e il dodicesimo non aveva ancora bevuto che già il primo era seduto e russava. Allora il Capo dei Ladri si liberò degli stracci da mendicante, prese un garzone dopo l’altro e con garbo li mise a cavalcioni dei divisori che separavano la scuderia, poi chiamò gli undici uomini che stavano aspettando fuori e cavalcarono via con i cavalli del Governatore.

Quando la mattina il Governatore venne a vedere i garzoni di stalla, quelli stavano cominciando a svegliarsi. Alcuni conficcavano gli speroni nel legno dei divisori tanto che ne schizzavano via schegge, altri cascavano e altri ancora restavano appesi guardandosi attorno come allocchi. “Bene,” disse il Governatore, “è facile capire chi sia stato qui; ma che razza di inutili esseri dovete essere per sedere qui e lasciare che il Capo dei Ladri vi sfili i cavalli da sotto!” E furono tutti bastonati per non aver fatto meglio la guardia.

Più tardi in quello stesso giorno il Capo dei Ladri venne e raccontò ciò che aveva fatto e voleva avere la figlia del Governatore come gli era stato promesso. Ma il Governatore gli diede un centinaio di monete e gli disse che doveva fare ancora di meglio.

”Pensi di poter rubare il mio cavallo mentre ci sto andando sopra?” disse.

”Beh, potrei farlo,” disse il Capo dei Ladri,”se è assolutamente certo che potrò prendere vostra figlia.”

Così il Governatore disse che avrebbe visto che cosa poteva fare, e poi gli disse che un certo giorno sarebbe andato a cavallo nella grande piazza dove si addestravano i soldati.

Allora il Capo dei Ladri immediatamente si procurò una giumenta sfiancata, si fece da solo un basto di giunchi verdi e di rami di ginestra; comprò un vecchio carro malandato e una grossa botte, poi disse a una povera e vecchia mendicante che le avrebbe dato dieci monete se fosse entrata nella botte e avesse tenuto la bocca bene aperta sotto il buco del tappo, nel quale lui avrebbe infilato un dito. Le disse che non le sarebbe accaduta nulla di male; dove solo lasciarsi trasportare per un po’ e se lui avesse tolto il dito più di una volta, avrebbe avuto altre dieci monete. Poi si vestì di stracci, si tinse con la fuliggine, indossò una parrucca e una gran barba di peli di capra, così che fosse impossibile riconoscerlo, e andò alla piazza d’armi, dove il Governatore stava cavalcando già da parecchio tempo.

Quando il Capo dei Ladri arrivò lì, la giumenta andava così piano e silenziosa che il carro quasi sembrava non muoversi da quel punto. La giumenta andava un po’ avanti e un po’ indietro, e si fermava abbastanza presto. Allora la giumenta andò avanti ancora un po’ e si muoveva con tale difficoltà che il Governatore non aveva la minima idea che quello fosse il Capo dei Ladri. Cavalcò vicino a lui e gli chiese se avesse visto qualcuno nascosto nel bosco lì vicino.

L’uomo disse: “No, non ho visto nessuno.”

”Ascolta,” disse il Governatore. “Se ti va di cavalcare nel bosco e cercare con attenzione se puoi scovare qualcuno nascosto lì, ti presterò il mio cavallo e ti farò un bel regalo per il tuo disturbo.”

”Non sono certo di poterlo fare,” disse l’uomo, “perché devo andare a un matrimonio con questa botte di idromele che sono andato a prendere, ma il tappo è caduto per strada, così adesso devo tenere il dito nel buco mentre guido.”

”Oh, vai,” disse il Governatore, “e sorveglierò io la botte e anche il cavallo.”

Così l’uomo disse che se doveva farlo, sarebbe andato, ma pregava il governatore di fare molta attenzione a infilare il dito nel buco del tappo nel momento in cui lui l’avesse estratto.

Allora il Governatore disse che avrebbe fatto del suo meglio e il Capo dei Ladri se ne andò con il cavallo del Governatore.

Ma il tempo passava, si faceva sempre più tardi, e ancora l’uomo non tornava indietro; alla fine il Governatore fu così stanco di tenere il dito nel buco del tappo che lo tolse.

”Adesso avrò dieci monete in più!” gridò la vecchia nella botte; così ben presto vide che razza di idromele fosse e se ne tornò verso casa. Aveva fatto ben poca strada quando incontrò il suo servitore che conduceva il cavallo, perché il Capo dei Ladri lo aveva già portato a casa.

Il giorno seguente andò dal Governatore e voleva avere sua figlia come gli era stato promesso. Ma di nuovo il Governatore lo blandì con belle parole e gli diede solo trecento monete, dicendogli che doveva compiere ancora un capolavoro di abilità, e che se ci fosse riuscito, l’avrebbe avuta.

Beh, il Capo dei Ladri pensò che avrebbe potuto sentire di che si trattava.

”Pensi di riuscire a rubare le lenzuola dal nostro letto e la camicia da notte di mia moglie?” disse il Governatore.

”Non mi sembra che sia impossibile,” disse il Capo dei Ladri. “Desidero solo poter avere senz’altro vostra figlia.”

Così a note fonda il Capo dei Ladri arrivò e tirò giù un ladro che pendeva dal patibolo, se lo caricò sulle spalle e lo portò via con sé. Poi si procurò una lunga scala, l’appoggiò contro la finestra della camera da letto del Governatore, si arrampicò e mosse la testa del morto su e giù, proprio come se fosse qualcuno che stava li fuori a spiare.

”Ecco il Capo dei Ladri, mamma!” disse il Governatore, dando una gomitata alla moglie. “Adesso gli sparerò, ecco che farò!”

Così prese un fucile che teneva accanto al letto.

”Oh, no, non devi farlo,” disse la moglie; “Hai fatto tu stesso in modo che venisse qui.”

”Invece sì, mamma, gli sparerò,” disse, e prese la mira e la prese ancora, perché un po’ la testa era su e poteva vederla e poi spariva. Infine ebbe l’occasione e fece fuoco, e il morto cadde con gran rumore sul terreno, e andò giù anche il capo dei Ladri, più in fretta che poté.

”Bene,” disse il Governatore, “I di certo qui son oil capo, ma la gente potrebbe parlare e sarebbe assai sgradevole se dovessero vedere il cadavere; la cosa migliore è che io lo porti via e lo seppellisca.”

”Fallo meglio che puoi, papà,” disse sua moglie.

Così il Governatore si alzo e scese di sotto; ed era appena uscito dalla porta che il Capo dei Ladri entrò furtivo e andò al piano superiore dalla donna.

”Beh, caro papa,” disse, perché pensava che fosse il marito. “Hai già fatto?”

”Oh, sì, l’ho solo gettato in una buca,” disse, “ l’ho coperto con un po’ di terra; per stanotte basta, perché fuori c’è un tempo terribile. Lo seppellirò meglio più tardi, ma adesso dammi il lenzuolo per asciugarmi perché era insanguinato e mi sono coperto di sangue trasportandolo.”

Così lei gli diede il lenzuolo.

”Dovresti darmi anche la tua camicia da notte,” disse, “perché mi rendo conto che il lenzuolo non basta.”

Allora gli diede la camicia da notte, ma subito gli venne in mente che aveva dimenticato di chiudere la porta e doveva per forza scendere al pianterreno e farlo, prima di rimettersi a letto. Così se ne andò con il lenzuolo e anche la camicia da note.

Un’ora più tardi il vero Governatore tornò.

”Beh, quanto tempo ti ci è volute per chiudere la porta di casa, papa!” disse la moglie, “e che ne hai fatto del lenzuolo e della camicia da notte?”

”Che significa?” chiese il Governatore.

”Oh, ti sto chiedendo che cosa hai fatto del lenzuolo e della camicia da notte che hai preso per asciugarti il sangue di dosso.” disse.

”Santo cielo!” disse il Governatore, “Ha avuto davvero di nuovo la meglio su di me?”

Quando si fu fatto giorno il Capo dei Ladri venne di nuovo e voleva avere la figlia del Governatore come gli era stato promesso; il Governatore non si azzardò a far altro che dargliela, con l’aggiunta di molte monete, perché aveva paura che se non l’avesse fatto, il Capo dei Ladri gli avrebbe rubato anche gli occhi dalla testa, e inoltre che tutti avrebbero sparlato di lui. Il Capo dei Ladri visse felice e contento da quel momento in poi, e se abbia mai più rubato qualcosa io non posso dirlo, ma se lo ha fatto, è stato solo come passatempo.

Da Peter Christen Asbjørnsen.

In appendice alla favola Lang riporta solo il nome di Asbjørnsen. In realtà Asbjørnsen, medico, naturalista e, si dice, gran camminatore, e Jørgen Moe, teologo poi salito fino alla dignità episcopale, raccolsero la tradizione orale delle fiabe norvegesi e le riunirono in un famoso volume. (NdT)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)