THERE was once upon a time a couple of rich folks who had twelve sons, and when the youngest was grown up he would not stay at home any longer, but would go out into the world and seek his fortune. His father and mother said that they thought he was very well off at home, and that he was welcome to stay with them; but he could not rest, and said that he must and would go, so at last they had to give him leave. When he had walked a long way, he came to a King’s palace. There he asked for a place and got it.

Now the daughter of the King of that country had been carried off into the mountains by a Troll, and the King had no other children, and for this cause both he and all his people were full of sorrow and affliction, and the King had promised the Princess and half his kingdom to anyone who could set her free; but there was no one who could do it, though a great number had tried. So when the youth had been there for the space of a year or so, he wanted to go home again to pay his parents a visit; but when he got there his father and mother were dead, and his brothers had divided everything that their parents possessed between themselves, so that there was nothing at all left for him.

‘Shall I, then, receive nothing at all of my inheritance?’ asked the youth.

‘Who could know that you were still alive—you who have been a wanderer so long?’ answered the brothers. ‘However, there are twelve mares upon the hills which we have not yet divided among us, and if you would like to have them for your share, you may take them.’

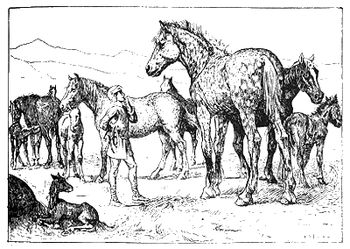

So the youth, well pleased with this, thanked them, and at once set off to the hill where the twelve mares were at pasture. When he got up there and found them, each mare had her foal, and by the side of one of them was a big dapple-grey foal as well, which was so sleek that it shone again.

‘Well, my little foal, you are a fine fellow!’ said the youth.

‘Yes, but if you will kill all the other little foals so that I can suck all the mares for a year, you shall see how big and handsome I shall be then!’ said the Foal.

So the youth did this—he killed all the twelve foals, and then went back again.

Next year, when he came home again to look after his mares and the foal, it was as fat as it could be, and its coat shone with brightness, and it was so big that the lad had the greatest difficulty in getting on its back, and each of the mares had another foal.

‘Well, it’s very evident that I have lost nothing by letting you suck all my mares,’ said the lad to the yearling; ‘but now you are quite big enough, and must come away with me.’

‘No,’ said the Colt, ‘I must stay here another year; kill the twelve little foals, and then I can suck all the mares this year also, and you shall see how big and handsome I shall be by summer.’

So the youth did it again, and when he went up on the hill next year to look after his colt and the mares, each of the mares had her foal again; but the dappled colt was so big that when the lad wanted to feel its neck to see how fat it was, he could not reach up to it, it was so high? and it was so bright that the light glanced off its coat.

‘Big and handsome you were last year, my colt, but this year you are ever so much handsomer,’ said the youth; ‘in all the King’s court no such horse is to be found. But now you shall come away with me.’

‘No,’ said the dappled Colt once more; ‘here I must stay for another year. Just kill the twelve little foals again, so that I can suck the mares this year also, and then come and look at me in the summer.’

So the youth did it—he killed all the little foals, and then went home again.

But next year, when he returned to look after the dappled colt and the mares, he was quite appalled. He had never imagined that any horse could become so big and overgrown, for the dappled horse had to lie down on all fours before the youth could get on his back, and it was very hard to do that even when it was lying down, and it was so plump that its coat shone and glistened just as if it had been a looking-glass. This time the dappled horse was not unwilling to go away with the youth, so he mounted it, and when he came riding home to his brothers they all smote their hands together and crossed themselves, for never in their lives had they either seen or heard tell of such a horse as that.

‘If you will procure me the best shoes for my horse, and the most magnificent saddle and bridle that can be found,’ said the youth, ‘you may have all my twelve mares just as they are standing out on the hill, and their twelve foals into the bargain.’ For this year also each mare had her foal. The brothers were quite willing to do this; so the lad got such shoes for his horse that the sticks and stones flew high up into the air as he rode away over the hills, and such a gold saddle and such a gold bridle that they could be seen glittering and glancing from afar.

‘And now we will go to the King’s palace,’ said Dapplegrim—that was the horse’s name, ‘but bear in mind that you must ask the King for a good stable and excellent fodder for me.’

So the lad promised not to forget to do that. He rode to the palace, and it will be easily understood that with such a horse as he had he was not long on the way.

When he arrived there, the King was standing out on the steps, and how he did stare at the man who came riding up!

‘Nay,’ said he, ‘never in my whole life have I seen such a man and such a horse.’

And when the youth inquired if he could have a place in the King’s palace, the King was so delighted that he could have danced on the steps where he was standing, and there and then the lad was told that he should have a place.

‘Yes; but I must have a good stable and most excellent fodder for my horse,’ said he.

So they told him that he should have sweet hay and oats, and as much of them as the dappled horse chose to have, and all the other riders had to take their horses out of the stable that Dapplegrim might stand alone and really have plenty of room.

But this did not last long, for the other people in the King’s Court became envious of the lad, and there was no bad thing that they would not have done to him if they had but dared. At last they bethought themselves of telling the King that the youth had said that, if he chose, he was quite able to rescue the Princess who had been carried off into the mountain a long time ago by the Troll.

The King immediately summoned the lad into his presence, and said that he had been informed that he had said that it was in his power to rescue the Princess, so he was now to do it. If he succeeded in this, he no doubt knew that the King had promised his daughter and half the kingdom to anyone who set her free, which promise should be faithfully and honourably kept, but if he failed he should be put to death. The youth denied that he had said this, but all to no purpose, for the King was deaf to all his words; so there was nothing to be done but say that he would make the attempt.

He went down into the stable, and very sad and full of care he was. Then Dapplegrim inquired why he was so troubled, and the youth told him, and said that he did not know what to do, ‘for as to setting the Princess free, that was downright impossible.’

‘Oh, but it might be done,’ said Dapplegrim. ‘I will help you; but you must first have me well shod. You must ask for ten pounds of iron and twelve pounds of steel for the shoeing, and one smith to hammer and one to hold.’

So the youth did this, and no one said him nay. He got both the iron and the steel, and the smiths, and thus was Dapplegrim shod strongly and well, and when the youth went out of the King’s palace a cloud of dust rose up behind him. But when he came to the mountain into which the Princess had been carried, the difficulty was to ascend the precipitous wall of rock by which he was to get on to the mountain beyond, for the rock stood right up on end, as steep as a house side and as smooth as a sheet of glass. The first time the youth rode at it he got a little way up the precipice, but then both Dapplegrim’s fore legs slipped, and down came horse and rider with a sound like thunder among the mountains. The next time that he rode at it he got a little farther up, but then one of Dapplegrim’s fore legs slipped, and down they went with the sound of a landslip. But the third time Dapplegrim said: ‘Now we must show what we can do,’ and went at it once more till the stones sprang up sky high, and thus they got up. Then the lad rode into the mountain cleft at full gallop and caught up the Princess on his saddle-bow, and then out again before the Troll even had time to stand up, and thus the Princess was set free.

When the youth returned to the palace the King was both happy and delighted to get his daughter back again, as may easily be believed, but somehow or other the people about the Court had so worked on him that he was angry with the lad too. ‘Thou shalt have my thanks for setting my Princess free,’ he said, when the youth came into the palace with her, and was then about to go away.

‘She ought to be just as much my Princess as she is yours now, for you are a man of your word,’ said the youth.

‘Yes, yes,’ said the King. ‘Have her thou shalt, as I have said it; but first of all thou must make the sun shine into my palace here.’

For there was a large and high hill outside the windows which overshadowed the palace so much that the sun could not shine in.

‘That was no part of our bargain,’ answered the youth. ‘But as nothing that I can say will move you, I suppose I shall have to try to do my best, for the Princess I will have.’

So he went down to Dapplegrim again and told him what the King desired, and Dapplegrim thought that it might easily be done; but first of all he must have new shoes, and ten pounds of iron and twelve pounds of steel must go to the making of them, and two smiths were also necessary, one to hammer and one to hold, and then it would be very easy to make the sun shine into the King’s palace.

The lad asked for these things and obtained them instantly, for the King thought that for very shame he could not refuse to give them, and so Dapplegrim got new shoes, and they were good ones. The youth seated himself on him, and once more they went their way, and for each hop that Dapplegrim made, down went the hill fifteen ells into the earth, and so they went on until there was no hill left for the King to see.

When the youth came down again to the King’s palace he asked the King if the Princess should not at last be his, for now no one could say that the sun was not shining into the palace. But the other people in the palace had again stirred up the King, and he answered that the youth should have her, and that he had never intended that he should not; but first of all he must get her quite as good a horse to ride to the wedding on as that which he had himself. The youth said that the King had never told him he was to do that, and it seemed to him that he had now really earned the Princess; but the King stuck to what he had said, and if the youth were unable to do it he was to lose his life, the King said. The youth went down to the stable again, and very sad and sorrowful he was, as anyone may well imagine. Then he told Dapplegrim that the King had now required that he should get the Princess as good a bridal horse as that which the bridegroom had, or he should lose his life. ‘But that will be no easy thing to do,’ said he, ‘for your equal is not to be found in all the world.’

‘Oh yes, there is one to match me,’ said Dapplegrim. ‘But it will not be easy to get him, for he is underground. However, we will try. Now you must go up to the King and ask for new shoes for me, and for them we must again have ten pounds of iron, twelve pounds of steel, and two smiths, one to hammer and one to hold, but be very particular to see that the hooks are very sharp. And you must also ask for twelve barrels of rye, and twelve slaughtered oxen must we have with us, and all the twelve ox-hides with twelve hundred spikes set in each of them; all these things must we have, likewise a barrel of tar with twelve tons of tar in it.’ The youth went to the King and asked for all the things that Dapplegrim had named, and once more, as the King thought that it would be disgraceful to refuse them to him, he obtained them all.

So he mounted Dapplegrim and rode away from the Court, and when he had ridden for a long, long time over hills and moors, Dapplegrim asked: ‘Do you hear anything?’

‘Yes; there is such a dreadful whistling up above in the air that I think I am growing alarmed,’ said the youth.

‘That is all the wild birds in the forest flying about; they are sent to stop us,’ said Dapplegrim. ‘But just cut a hole in the corn sacks, and then they will be so busy with the corn that they will forget us.’

The youth did it. He cut holes in the corn sacks so that barley and rye ran out on every side, and all the wild birds that were in the forest came in such numbers that they darkened the sun. But when they caught sight of the corn they could not refrain from it, but flew down and began to scratch and pick at the corn and rye, and at last they began to fight among themselves, and forgot all about the youth and Dapplegrim, and did them no harm.

And now the youth rode onwards for a long, long time, over hill and dale, over rocky places and morasses, and then Dapplegrim began to listen again, and asked the youth if he heard anything now.

‘Yes; now I hear such a dreadful crackling and crashing in the forest on every side that I think I shall be really afraid,’ said the youth.

‘That is all the wild beasts in the forest,’ said Dapplegrim; ‘they are sent out to stop us. But just throw out the twelve carcasses of the oxen, and they will be so much occupied with them that they will quite forget us.’ So the youth threw out the carcasses of the oxen, and then all the wild beasts in the forest, both bears and wolves, and lions, and grim beasts of all kinds, came. But when they caught sight of the carcasses of the oxen they began to fight for them till the blood flowed, and they entirely forgot Dapplegrim and the youth.

So the youth rode onwards again, and many and many were the new scenes they saw, for travelling on Dapplegrim’s back was not travelling slowly, as may be imagined, and then Dapplegrim neighed.

‘Do you hear anything? he said.

‘Yes; I heard something like a foal neighing quite plainly a long, long way off,’ answered the youth.

‘That’s a full-grown colt,’ said Dapplegrim, ‘if you hear it so plainly when it is so far away from us.’

So they travelled onwards a long time, and saw one new scene after another once more. Then Dapplegrim neighed again.

‘Do you hear anything now?’ said he.

‘Yes; now I heard it quite distinctly, and it neighed like a full-grown horse,’ answered the youth.

‘Yes, and you will hear it again very soon,’ said Dapplegrim; ‘and then you will hear what a voice it has.’ So they travelled on through many more different kinds of country, and then Dapplegrim neighed for the third time; but before he could ask the youth if he heard anything, there was such a neighing on the other side of the heath that the youth thought that hills and rocks would be rent in pieces.

‘Now he is here!’ said Dapplegrim. ‘Be quick, and fling over me the ox-hides that have the spikes in them, throw the twelve tons of tar over the field, and climb up into that great spruce fir tree. When he comes, fire will spurt out of both his nostrils, and then the tar will catch fire. Now mark what I say—if the flame ascends I conquer, and if it sinks I fail; but if you see that I am winning, fling the bridle, which you must take off me, over his head, and then he will become quite gentle.’

Just as the youth had flung all the hides with the spikes over Dapplegrim, and the tar over the field, and had got safely up into the spruce fir, a horse came with flame spouting from his nostrils, and the tar caught fire in a moment; and Dapplegrim and the horse began to fight until the stones leapt up to the sky. They bit, and they fought with their fore legs and their hind legs, and sometimes the youth looked at them and sometimes he looked at the tar, but at last the flames began to rise, for wheresoever the strange horse bit or wheresoever he kicked, he hit upon the spikes in the hides, and at length he had to yield. When the youth saw that, he was not long in getting down from the tree and flinging the bridle over the horse’s head, and then he became so tame that he might have been led by a thin string.

This horse was dappled too, and so like Dapplegrim that no one could distinguish the one from the other. The youth seated himself on the dappled horse which he had captured, and rode home again to the King’s palace, and Dapplegrim ran loose by his side. When he got there, the King was standing outside in the courtyard.

‘Can you tell me which is the horse I have caught, and which is the one I had before?’ said the youth. ‘If you can’t, I think your daughter is mine.’

The King went and looked at both the dappled horses; he looked high and he looked low, he looked before and he looked behind, but there was not a hair’s difference between the two.

‘No,’ said the King; ‘that I cannot tell thee, and as thou hast procured such a splendid bridal horse for my daughter thou shalt have her; but first we must have one more trial, just to see if thou art fated to have her. She shall hide herself twice, and then thou shalt hide thyself twice. If thou canst find her each time that she hides herself, and if she cannot find thee in thy hiding-places, then it is fated, and thou shalt have the Princess.’

‘That, too, was not in our bargain,’ said the youth. ‘But we will make this trial since it must be so.’

So the King’s daughter was to hide herself first.

Then she changed herself into a duck, and lay swimming in a lake that was just outside the palace. But the youth went down into the stable and asked Dapplegrim what she had done with herself.

‘Oh, all that you have to do is to take your gun, and go down to the water and aim at the duck which is swimming about there, and she will soon discover herself,’ said Dapplegrim.

The youth snatched up his gun and ran to the lake. ‘I will just have a shot at that duck,’ said he, and began to aim at it.

‘Oh, no, dear friend, don’t shoot! It is I,’ said the Princess. So he had found her once.

The second time the Princess changed herself into a loaf, and laid herself on the table among four other loaves; and she was so like the other loaves that no one could see any difference between them.

But the youth again went down to the stable to Dapplegrim, and told him that the Princess had hidden herself again, and that he had not the least idea what had become of her.

‘Oh, just take a very large bread-knife, sharpen it, and pretend that you are going to cut straight through the third of the four loaves which are lying on the kitchen table in the King’s palace—count them from right to left—and you will soon find her,’ said Dapplegrim.

So the youth went up to the kitchen, and began to sharpen the largest bread-knife that he could find; then he caught hold of the third loaf on the left-hand side, and put the knife to it as if he meant to cut it straight in two. ‘I will have a bit of this bread for myself,’ said he.

‘No, dear friend, don’t cut, it is I!’ said the Princess again; so he had found her the second time.

And now it was his turn to go and hide himself; but Dapplegrim had given him such good instructions that it was not easy to find him. First he turned himself into a horse-fly, and hid himself in Dapplegrim’s left nostril. The Princess went poking about and searching everywhere, high and low, and wanted to go into Dapplegrim’s stall too, but he began to bite and kick about so that she was afraid to go there, and could not find the youth. ‘Well,’ said she, ‘as I am unable to find you, you must show yourself.’ Whereupon the youth immediately appeared standing there on the stable floor.

Dapplegrim told him what he was to do the second time, and he turned himself into a lump of earth, and stuck himself between the hoof and the shoe on Dapplegrim’s left fore foot. Once more the King’s daughter went and sought everywhere, inside and outside, until at last she came into the stable, and wanted to go into the stall beside Dapplegrim. So this time he allowed her to go into it, and she peered about high and low, but she could not look under his hoofs, for he stood much too firmly on his legs for that, and she could not find the youth.

‘Well, you will just have to show where you are yourself, for I can’t find you,’ said the Princess, and in an instant the youth was standing by her side on the floor of the stable.

‘Now you are mine!’ said he to the Princess.

‘Now you can see that it is fated that she should be mine,’ he said to the King.

‘Yes, fated it is,’ said the King. ‘So what must be, must.’

Then everything was made ready for the wedding with great splendour and promptitude, and the youth rode to church on Dapplegrim, and the King’s daughter on the other horse. So everyone must see that they could not be long on their way thither.

From J. Møe.

Dapplegrim

C’era una volta una coppia di ricchi agricoltori che avevano dodici figli e quando il più giovane fu cresciuto, non volle restare a casa più a lungo ma volle andare in giro per il mondo in cerca di fortuna. Il padre e la madre dissero che pensavano sarebbe stato molto bene a casa e che era libero di restare con loro, ma lui non volle rimanere e disse che doveva andare e sarebbe andato, così alla fine gli diedero il permesso. Quando ebbe camminato per un bel po’, giunse al palazzo del re. lì chiese di essere preso a servizio e l’ottenne.

Si dava il caso che la figlia del re di quel paese fosse stata portata tra le montagne da un troll e che il re non avesse altri figli, e per questo motivo sia lui che tutto il popolo erano molto addolorati e in pena; il re aveva promesso la mano della principessa e metà del regno a chiunque l’avesse liberata; però non c’era riuscito nessuno, sebbene avessero tentato in tanti. Così quando il giovane era lì da circa un anno, volle tornare a casa a far di nuovo visita ai genitori; ma quando fu a casa, il padre e la madre erano morti e i fratelli si erano divisi tra loro tutto ciò che avevano posseduto i genitori così che per lui non era rimasto nulla.

“Ebbene, allora non riceverò nulla dell’eredità?” chiese il ragazzo.

“Chi poteva sapere che tu fossi ancora vivo… sei stato via così a lungo!” risposero i fratelli. “In ogni modo sulle colline ci sono dodici giumente che non ci siamo divise tra noi e se vuoi averle come tua parte di eredità, puoi prenderle.”

Così il ragazzo, ben contento di ciò, li ringraziò e andò subito sulla collina dove stavano pascolando le dodici giumente. Quando fu salito là e le ebbe trovate, ogni giumenta aveva un puledrino e a fianco di una di esse ce n’era uno grosso, grigio pezzato, così florido che scintillava.

“Beh, puledrino mio, sei proprio bello!” disse il ragazzo.

“Sì, ma se ucciderai gli altri dodici puledri così che io possa poppare da tutte le giumente per un anno, vedrai allora come sarò diventato grande e bello!” disse il puledro.

E così fece il ragazzo: uccise tutti i puledri e se ne andò di nuovo.

L’anno successive, quando tornò di nuovo a casa per vedere le giumente e il puledro, questi era così florido, con il pelo così lucente, e così grosso che ebbe gran difficoltà a salirgli in groppa, e ogni giumenta aveva avuto un altro puledro.

“È evidente che non ci ho rimesso nel lasciarti poppare da tutte le giumente,” disse il ragazzo al puledro “ma adesso sei abbastanza grande e devi venire via con me.”

Il puledro rispose. “No, devo stare qui un altro anno; uccidi i puledrini e allora io potrò poppare tutte le giumente per un altro anno ancora e vedrai l’estate prossima come sarò diventato grande e bello.”

Così il ragazzo lo fece di nuovo e quando andò sulla collina l’anno successivo a vedere il puledro e le giumente, ognuna di loro aveva avuto un altro puledro ma quello pezzato era così grande che quando il ragazzo volle sentirgli il collo per vedere quanto fosse grasso, non poté raggiungerlo per quanto era alto ed era così lucente che la luce quasi scaturiva dal suo manto.

“L’anno scorso eri grande e bello, puledro mio, ma quest’anno lo sei ancora di più,” disse il ragazzo “in tutta la corte del re non si trova un cavallo simile. Adesso devi venire via con me.”

Il puledro disse ancora una volta: “No, devo stare qui un altro anno. Uccidi di nuovo tutti i puledrini, così che io possa poppare le giumente ancora quest’anno, e poi vieni a vedermi la prossima estate.”

Il ragazzo fece così, uccise tutti i puledrini e tornò a casa.

Ma l’anno successivo, quando tornò a vedere il puledro pezzato e le giumente, fu assai spaventato. Non avrebbe mai immaginato che un cavallo potesse diventare così grande e grosso, per cui il cavallo pezzato dovette piegarsi sulle quattro zampe prima che il ragazzo potesse arrivare al suo dorso e fu assai difficile farlo sebbene fosse sdraiato, e ed era così florido che il suo manto scintillava e brillava come se fosse uno specchio. Stavolta il puledro non si rifiutò di andar via con il ragazzo, così gli montò in groppa e quando giunse al galoppo a casa dei fratelli, questi giunsero le mani e si fecero il segno della croce perché in tutta la loro vita non avevano mai visto o sentito parlare di un cavallo come quello.

“Se mi procurerete i ferri migliori per il mio cavallo e la sella e le briglie più belle che possiate trovare,” disse il ragazzo “potrete avere in cambio tutte e dodici le giumente che si trovano sulla collina e i loro puledri.” Perché anche quell’anno ogni giumenta aveva avuto un puledrino. I fratelli accettarono volentieri così il ragazzo ebbe per il suo cavallo dei ferri tali che rametti e pietre schizzavano in aria quando cavalcava sulle colline e una sella e delle briglie d’oro così lucenti che si potevano veder scintillare da lontano.

“Adesso andiamo al palazzo del re,” disse Dapplegrim– perché era questo il nome del cavallo – ma tieni bene a mente che devi chiedere al re una buona stalla e biada eccellente per me.”

Così il ragazzo promise di non dimenticarlo. Cavalcarono fino al palazzo e si può bene capire che un cavallo simile non ci mise molto tempo.

Quando arrivarono là, il re era sugli scalini e fissava l’uomo che stava arrivando a cavallo!

“In tutta la mia vita non ho mai visto un uomo e un cavallo così!” disse.

Quando il ragazzo chiese se ci fosse un posto di lavoro nel palazzo del re, il sovrano ne fu così contento da ballare sugli scalini sui quali si trovava e in men che non si dica fu detto al ragazzo che avrebbe avuto un posto.

“D’accordo, ma devo avere una buona stalla e la biada più eccellente per il mio cavallo.” disse il ragazzo.

Così gli fu detto che avrebbe avuto fieno dolce e aveva quanta ne chiedesse il cavallo pezzato e che gli altri cavalieri avrebbe condotto fuori dalla stalla i loro cavalli affinché Dapplegrim potesse star solo e avere abbondanza di spazio.

Questa situazione però non durò a lungo perché gli altri cortigiani erano invidiosi del ragazzo e non c’erano azioni cattive che non avrebbero commesso contro di lui se solo avessero osato. Alla fine pensarono di raccontare al re che il ragazzo aveva detto che, se lo avesse scelto, sarebbe stato capace di salvare la principessa che era stata portata sulla montagna dal troll tanto tempo prima.

Il re convocò immediatamente il ragazzo e gli disse di essere stato informato che lui avesse detto di essere in grado di salvare la principessa, così adesso doveva farlo. Se avesse avuto successo, senza dubbio sapeva che il re aveva promesso la figlia e metà del regno a chiunque l’avesse liberata, promessa che sarebbe stata mantenuta con fede e onore, ma se avesse fallito, sarebbe stato messo a morte. Il ragazzo negò di averlo mai detto ma non servì a nulla perché il re fu sordo alle sue parole, così non gli rimase altro da dire che avrebbe tentato.

Il ragazzo andò nella stalla e si sentiva assai triste e preoccupato. Allora Dapplegrim chiese perché fosse così afflitto e il ragazzo glielo raccontò, dicendogli di non sapere che fare “perché liberare la principessa era assolutamente impossibile.”

“Si potrebbe fare,” disse Dapplegrim “ti aiuterò io, ma prima dovrò essere ben ferrato. Devi chiedere dieci libbre di ferro e dodici libbre di acciaio per i ferri, e un fabbro per battere il ferro e uno per ferrarmi.”

Il giovane fece così e nessuno gli disse di no. Ebbe sia il ferro e l’acciaio che i fabbri e così Dapplegrim fu ferrato solidamente e ben bene e quando il ragazzo lasciò il palazzo del re, dietro di lui si sollevò una nuvola di polvere. Quando giunsero alla montagna nella quale era stata condotta la principessa, la difficoltà fu scalare la scoscesa parete di roccia che l’avrebbe condotto oltre la montagna perché la roccia si ergeva sino alla cima ripida come la parete di una casa e liscia come una lastra di vetro. La prima volta in cui il ragazzo provò a salire con il cavallo, riuscì a farlo un po’ sulla parete scoscesa, poi entrambe le zampe anteriori di Dapplegrim scivolarono e cavallo e cavaliere tornarono giù con un rumore simile al tuono tra le montagne. La volta successiva che salì col cavallo, avanzò un pezzetto di più, ma una delle zampe anteriori di Dapplegrim scivolò e ricaddero giù con il rumore di una frana. La terza volta Dapplegrim disse: “Adesso dobbiamo mostrare che cosa sappiamo fare.” e si slanciò avanti ancora una volta, facendo schizzare le pietre fino al cielo e così arrivarono in cima. Allora il ragazzo entrò a spron battuto nella montagna e afferrò la principessa sulla sella poi uscì di nuovo prima che il troll avesse il tempo di alzarsi e così la principessa fu libera.

Quando il giovane tornò al palazzo, il re fu tanto felice e di riavere indietro la figlia che quasi non ci credeva, ma in un modo o nell’altro i cortigiani si diedero da fare e infine egli se la prese con il ragazzo. “Hai la mia gratitudine per aver liberato la mia principessa.” gli disse, quando il ragazzo entrò con lei a palazzo, e fece per andarsene.

“Dovrebbe essere tanto la mia principessa quanto ora è vostra perché siete un uomo di parola.” disse il ragazzo.

Il re rispose: “Sì, sì, l’avrai, come ho detto, ma prima di tutto dovrai riuscire a far splendere il sole qui nel mio palazzo.”

Il fatto era che un’ampia e alta collina si ergeva davanti alle finestre e faceva una tale ombra al palazzo che non vi entrava mai il sole.

“Questo non faceva parte del patto,” rispose il ragazzo “ma siccome nulla di ciò che potrei dirvi vi smuoverà, suppongo di dover fare del mio meglio perché voglio avere la principessa.”

Così andò di nuovo da Dapplegrim e gli disse ciò che il re voleva e il cavallo pensò che si potesse fare facilmente; prima di tutto però doveva avere nuovi ferri e sarebbero serviti per farli dieci libbre di ferro, dodici libbre d’acciaio e due fabbri, uno per battere il ferro e uno per ferrarlo, poi sarebbe stato facile portare la luce del sole dentro il palazzo del re.

Il ragazzo chiese quelle cose e le ottenne subito perché il re pensò che sarebbe stata una vergogna se avesse rifiutato di dargliele, così Dapplegrim ebbe nuovi ferri ed erano ottimi. Il giovane montò in sella e subito s’incamminarono e a ogni passo che Dapplegrim faceva, la collina sprofondava di quindici braccia nel terreno e così andarono avanti finché al re non rimase più nessuna collina da vedere.

Quando il ragazzo tornò di nuovo al palazzo del re, chiese al sovrano se infine la principessa fosse sua perché nessuno poteva dire che il sole non brillasse nel palazzo. Ma i cortigiani avevano di nuovo istigato il re, il quale rispose che l’avrebbe avuta e che non aveva mai inteso negargliela, ma prima di tutto doveva procurarle un cavallo bello come il suo per recarsi al matrimonio. Il ragazzo rispose che non gli aveva mai detto di doverlo fare e gli sembrava di essersi proprio guadagnato la principessa, ma il re fu irremovibile e disse che, se il giovane non fosse stato capace di farlo, ci avrebbe rimesso la vita. Il ragazzo andò di nuovo nella stalla ed era assai triste e addolorato, come potete ben immaginare. Poi raccontò a Dapplegrim che il re gli aveva chiesto di procurare alla principessa un cavallo pari al proprio per le nozze o ci avrebbe rimesso la vita. “Non sarà facile farlo,” disse il ragazzo “perché in tutto il mondo non si trova un tuo simile.”

“Sì che ce n’è uno come me,” disse Dapplegrim “ma non sarà facile ottenerlo perché si trova nel sottosuolo. In ogni modo tenteremo. Adesso devi andare dal re e chiedergli nuovi ferri per me e per essi devo avere di nuovo dieci libbre di ferro, dodici libbre d’acciaio e due fabbri, uno per battere il ferro e uno per ferrarmi, ma la particolarità è che i chiodi dovranno essere molto appuntiti. E devi chiedere anche dodici botti di orzo e dodici carcasse di buoi, che porteremo con noi, e tutte e dodici le pelli dei buoi con milleduecento chiodi piantati in ciascuna; dobbiamo avere tutte queste cose così anche una botte con dodici tonnellate di catrame.” Il ragazzo andò dal re e gli chiese tutto ciò che aveva detto Dapplegrim, e ancora una volta l’ottenne perché il re pensò che sarebbe stato disonorevole rifiutarglielo.

Così montò in sella a Dapplegrim e lasciò la corte; dopo che ebbero cavalcato per molto, molto tempo oltre colline e brughiere, Dapplegrim chiese: “Senti qualcosa?”

“Sì, c’è un fischio così spaventoso in aria che quasi quasi mi sta venendo paura.” disse il ragazzo.

“Sono tutti gli uccelli selvatici che stanno arrivando al volo nella foresta; li hanno mandati pere fermarci.” disse Dapplegrim. “Fai un buco nelle botti d’orzo e saranno troppo occupati con esso che si dimenticheranno di noi.”

Il ragazzo lo fece. Praticò dei buchi nelle botti così che l’orzo ruzzolò da ogni parte e tutti gli uccelli che erano nella foresta vennero in tal numero da oscurare il sole. Ma quando videro i chicchi, non seppero trattenersi e si tuffarono a capofitto e cominciarono ad artigliare e a spilluzzicare l’orzo e infine cominciarono a lottare fra loro e dimenticarono completamente il ragazzo e Dapplegrim e non fecero loro del male.

Il ragazzo cavalcò ancora per molto molto tempo, oltre le colline e le valli, oltre le pianure sassose e gli acquitrini, e allora Dapplegrim cominciò di nuovo ad ascoltare e chiese al ragazzo se adesso sentisse qualcosa.

“Sì, adesso sento spaventosi scricchiolii da ogni parte nella foresta e sto cominciando ad avere paura.” disse il ragazzo.

Dapplegrim rispose: “Sono tutte le bestie selvagge della foresta, mandate per fermarci. Getta le dodici carcasse di buoi e saranno così occupate con esse che si dimenticheranno completamente di noi.” Così il ragazzo gettò le carcasse dei buoi e allora vennero tutte le bestie feroci della foresta, sia orsi che lupi, e leoni e belve di ogni genere. Quando videro le carcasse dei buoi cominciarono a contendersele finché scorse il sangue e si dimenticarono completamente di Dapplegrim e del ragazzo.

Così il ragazzo cavalcò via di nuovo e molti furono i paesaggi che videro perché viaggiare sul dorso di Dapplegrim non voleva dire viaggiare lentamente, come potete ben immaginare, e poi Dapplegrim nitrì.

“Senti qualcosa?” disse

“Sì, sento piuttosto distintamente qualcosa come il nitrito di un puledro molto lontano.” rispose il ragazzo.

Dapplegrim disse: “Deve essere un puledro ben cresciuto, se lo senti così distintamente quando è così lontano da noi.”

Così viaggiarono ancora per molto tempo e videro un nuovo paesaggio dopo l’altro. Allora Dapplegrim nitrì di nuovo.

“Senti qualcosa adesso?” chiese.

“Sì, sento piuttosto distintamente ed è il nitrito di un puledro ben cresciuto.” rispose il ragazzo.

“Sì, e lo sentirai nuovo molto presto,” disse Dapplegrim “e allora sentirai che voce ha.” Così viaggiarono attraverso diversi tipi di paesi e poi Dapplegrim nitrì per la terza volta; ma prima che chiedesse al ragazzo se sentisse qualcosa, ci fu un tale nitrito dall’altra parte della brughiera che il ragazzo pensò che le colline e le pareti rocciose stessero andando in pezzi.

“Adesso è qui!” disse Dapplegrim “Svelto, getta su di me le pelli di bue con i chiodi infilzati, buttale dodici tonnellate di pece sul campo e arrampicati su quel grande abete. Quando si avvicinerà, il fuoco gli uscirà dalle narici e allora la pece s’incendierà. Bada bene a ciò che ti dico: se le fiamme salgono, io vincerò, se scendono io fallirò, ma se vedi che sarò io a vincere, mettigli pure sulla testa le briglie che ora mi toglierai e allora diventerà docile.”

Appena il ragazzo ebbe steso le pelli con i chiodi su Dapplegrim e la pece sul campo, giunse un cavallo che lanciava fiamme dalle narici e la pece prese fuoco in un attimo; Dapplegrim e il cavallo cominciarono a lottare tanto che le pietre schizzavano verso il cielo. Si morsero, combatterono con le zampe anteriori e quelle posteriori, e a volte al ragazzo guardava loro e a volte la pece, ma infine le fiamme cominciarono a salire perché dovunque lo strano cavallo mordesse o calciasse, veniva colpito dai chiodi e alla fine dovette arrendersi. Quando il ragazzo vide ciò, si affrettò a scendere dall’albero e a gettare le briglie intorno alla testa del cavallo e allora divenne così mansueto che avrebbe potuto condurlo con una sottile corda.

Anche questo cavallo era pezzato come Dapplegrim e nessuno avrebbe potuto distinguere l’uno dall’altro. Il ragazzo montò il cavallo pezzato che aveva catturato e cavalcò verso il palazzo del re con Dapplegrim che gli cavalcava libero al fianco. Quando fu là, il re era in cortile.

“Potete dirmi quale sia il cavallo che ho catturato e quale sia quello che avevo prima?” chiese il ragazzo. “Se non potete, vostra figlia è mia.”

Il re si mosse e osservò entrambi i cavalli pezzati: guardò su e giù, guardò davanti e dietro, ma non c’era la minima differenza tra i due animali.

Il re disse: “No, non posso dirtelo e siccome hai procurato un così splendido cavallo per le nozze di mia figlia, l’avrai; ma prima c’è ancora una prova, solo per vedere se sei degno di lei. Si nasconderà due volte e a tua volta dovrai nasconderti due volte. Se riuscirai a trovarla ogni volta in cui si sarà nascosta e lei non riuscirà a trovare te nei tuoi nascondigli, allora sarà destino e tu avrai la principessa.”

“Anche ciò non era nel nostro patto,” disse il ragazzo “ma ci sarà questa prova, se così deve essere.”

Così la figlia del re si nascose per prima.

Quindi si trasformò in un’anatra e nuotò nel laghetto che stava proprio davanti al palazzo, ma il ragazzo andò nella stalla e chiese a Dapplegrim che cosa lei avesse fatto.

“Tutto ciò che devi fare è prendere il tuo fucile e scendere al lago, prendere di mira l’anatra che sta nuotando là e vedrai che lei si mostrerà.” disse Dapplegrim.

Il ragazzo afferrò il fucile e corse al lago. “Tirerò un colpo proprio a quell’anatra.” disse, e prese la mira.

“No, amico caro, non sparare! Sono io!” disse la principessa. Così l’ebbe trovata una volta.

La seconda volta la principessa si trasformò in una pagnotta e si mise sul tavolo in mezzo ad altre pagnotte. Era così simile alle altre che non si sarebbe potuta vedere alcuna differenza fra di esse.

Il ragazzo andò di nuovo nella stalla da Dapplegrim e gli disse che la principessa si era nascosta di nuovo, ma che lui non aveva la minima idea di come fosse diventata.

“Devi solo prendere un grosso coltello, affilarlo e fingere di voler affettare proprio la terza delle quattro pagnotte che sono sul tavolo della cucina nel palazzo del re – contando da destra a sinistra – e la troverai presto.” disse Dapplegrim.

Così il ragazzo andò in cucina e cominciò ad affilare il coltello più grande che poté trovare: poi gettò un’occhiata alla terza pagnotta dal lato sinistro ed estrasse il coltello come se volesse tagliarla in due. “Mi prenderò un pezzo di questo pane.” disse.

“No, caro amico, non tagliare, sono io!” disse la principessa, così fu trovata per la seconda volta.

Adesso toccava al ragazzo andare a nascondersi, ma Dapplegrim gli aveva dato istruzioni così utili che non era facile trovarlo. Prima si trasformò in una mosca cavallina e si nascose nella narice sinistra di Dapplegrim. La principessa andò in cerca all’intorno, guardando dappertutto, su e giù, e volle andare anche nella stalla di Dapplegrim, ma il cavallo cominciò a mordere e a scalciare così che ebbe paura di avvicinarsi e non poté trovare il ragazzo. La principessa disse: “Ebbene, non riesco a trovarti, devi mostrarti da solo.” Al che il ragazzo comparve immediatamente lì nella stalla.

Dapplegrim gli disse che cosa doveva fare la seconda volta e il ragazzo si trasformò in un granello di terra e si nascose tra lo zoccolo e il fero della zampa anteriore sinistra di Dapplegrim. Ancora una volta la figlia del re venne a cercarlo dappertutto, dentro e fuori, finché alla fine giunse nella stalla e volle guardarvi dentro il recinto di Dapplegrim. Stavolta le permise di entrare e lei scrutò in alto e in basso, ma non poté guardare sotto gli zoccoli perché stava ben saldo sulle zampe e per questo motivo lei non poté trovare il ragazzo.

“Ebbene, mostra da solo dove sei perché non posso trovarti.” disse la principessa e in un istante il ragazzo fu accanto a lei sul pavimento della stalla.

“Adesso sei mia!” disse il ragazzo alla principessa.

“Adesso vedete che era destino fosse mia.” disse il ragazzo al re.

Il re disse: “Sì, era destino. Ciò che deve essere, sia.”

Allora tutto fu approntato con grande magnificenza e pompa per le nozze e il ragazzo cavalcò verso la chiesa su Dopplegrim mentre la principessa cavalcò l’altro cavallo. Potete ben vedere da voi che entrambi non ci misero molto a percorrere il tragitto.

Da Jorgen Møe

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)