The Twelve Brothers

(MP3-10'13'')

THERE were once upon a time a King and a Queen who lived happily together, and they had twelve children, all of whom were boys. One day the King said to his wife:

‘If our thirteenth child is a girl, all her twelve brothers must die, so that she may be very rich and the kingdom hers alone.’

Then he ordered twelve coffins to be made, and filled them with shavings, and placed a little pillow in each. These he put away in an empty room, and, giving the key to his wife, he bade her tell no one of it.

The Queen grieved over the sad fate of her sons and refused to be comforted, so much so that the youngest boy, who was always with her, and whom she had christened Benjamin, said to her one day:

‘Dear mother, why are you so sad?’

‘My child,’ she answered, ‘I may not tell you the reason.’

But he left her no peace, till she went and unlocked the room and showed him the twelve coffins filled with shavings, and with the little pillow laid in each.

Then she said: ‘My dearest Benjamin, your father has had these coffins made for you and your eleven brothers, because if I bring a girl into the world you are all to be killed and buried in them.’

She wept bitterly as she spoke, but her son comforted her and said:

‘Don’t cry, dear mother; we’ll manage to escape somehow, and will fly for our lives.’

‘Yes,’ replied his mother, ‘that is what you must do—go with your eleven brothers out into the wood, and let one of you always sit on the highest tree you can find, keeping watch on the tower of the castle. If I give birth to a little son I will wave a white flag, and then you may safely return; but if I give birth to a little daughter I will wave a red flag, which will warn you to fly away as quickly as you can, and may the kind Heaven have pity on you. Every night I will get up and pray for you, in winter that you may always have a fire to warm yourselves by, and in summer that you may not languish in the heat.’

Then she blessed her sons and they set out into the wood. They found a very high oak tree, and there they sat, turn about, keeping their eyes always fixed on the castle tower. On the twelfth day, when the turn came to Benjamin, he noticed a flag waving in the air, but alas! it was not white, but blood red, the sign which told them they must all die. When the brothers heard this they were very angry, and said:

‘Shall we forsooth suffer death for the sake of a wretched girl? Let us swear vengeance, and vow that wherever and whenever we shall meet one of her sex, she shall die at our hands.’

Then they went their way deeper into the wood, and in the middle of it, where it was thickest and darkest, they came upon a little enchanted house which stood empty.

‘Here,’ they said, ‘let us take up our abode, and you, Benjamin, you are the youngest and weakest, you shall stay at home and keep house for us; we others will go out and fetch food.’ So they went forth into the wood, and shot hares and roe-deer, birds and wood-pigeons, and any other game they came across. They always brought their spoils home to Benjamin, who soon learnt to make them into dainty dishes. So they lived for ten years in this little house, and the time slipped merrily away.

In the meantime their little sister at home was growing up quickly. She was kind-hearted and of a fair countenance, and she had a gold star right in the middle of her forehead. One day a big washing was going on at the palace, and the girl looking down from her window saw twelve men’s shirts hanging up to dry, and asked her mother:

‘Who in the world do these shirts belong to? Surely they are far too small for my father?’

And the Queen answered sadly: ‘Dear child, they belong to your twelve brothers.’

‘But where are my twelve brothers?’ said the girl. ‘I have never even heard of them.’

‘Heaven alone knows in what part of the wide world they are wandering,’ replied her mother.

Then she took the girl and opened the locked-up room; she showed her the twelve coffins filled with shavings, and with the little pillow laid in each.

‘These coffins,’ she said, ‘were intended for your brothers, but they stole secretly away before you were born.’

Then she to tell her all that had happened, and when she had finished her daughter said:

‘Do not cry, dearest mother; I will go and seek my brothers till I find them.’

So she took the twelve shirts and went on straight into the middle of the big wood. She walked all day long, and came in the evening to the little enchanted house. She stepped in and found a youth who, marvelling at her beauty, at the royal robes she wore, and at the golden star on her forehead, asked her where she came from and whither she was going.

‘I am a Princess,’ she answered, ‘and am seeking for my twelve brothers. I mean to wander as far as the blue sky stretches over the earth till I find them.’

Then she showed him the twelve shirts which she had taken with her, and Benjamin saw that it must be his sister, and said:

‘I am Benjamin, your youngest brother.’

So they wept for joy, and kissed and hugged each other again and again. After a time Benjamin said:

‘Dear sister, there is still a little difficulty, for we had all agreed that any girl we met should die at our hands, because it was for the sake of a girl that we had to leave our kingdom.’

‘But,’ she replied, ‘I will gladly die if by that means I can restore my twelve brothers to their own.’

‘No,’ he answered, ‘there is no need for that; only go and hide under that tub till our eleven brothers come in, and I’ll soon make matters right with them.’

She did as she was bid, and soon the others came home from the chase and sat down to supper.

‘Well, Benjamin, what’s the news?’ they asked. But he replied, ‘I like that; have you nothing to tell me?’

‘No,’ they answered.

Then he said: ‘Well, now, you’ve been out in the wood all the day and I’ve stayed quietly at home, and all the same I know more than you do.’

‘Then tell us,’ they cried.

But he answered: ‘Only on condition that you promise faithfully that the first girl we meet shall not be killed.’

‘She shall be spared,’ they promised, ‘only tell us the news.’

Then Benjamin said: ‘Our sister is here!’ and he lifted up the tub and the Princess stepped forward, with her royal robes and with the golden star on her forehead, looking so lovely and sweet and charming that they all fell in love with her on the spot.

They arranged that she should stay at home with Benjamin and help him in the house work, while the rest of the brothers went out into the wood and shot hares and roe-deer, birds and wood-pigeons. And Benjamin and his sister cooked their meals for them. She gathered herbs to cook the vegetables in, fetched the wood, and watched the pots on the fire, and always when her eleven brothers returned she had their supper ready for them. Besides this, she kept the house in order, tidied all the rooms, and made herself so generally useful that her brothers were delighted, and they all lived happily together.

One day the two at home prepared a fine feast, and when they were all assembled they sat down and ate and drank and made merry.

Now there was a little garden round the enchanted house, in which grew twelve tall lilies. The girl, wishing to please her brothers, plucked the twelve flowers, meaning to present one to each of them as they sat at supper. But hardly had she plucked the flowers when her brothers were turned into twelve ravens, who flew croaking over the wood, and the house and garden vanished also.

So the poor girl found herself left all alone in the wood, and as she looked round her she noticed an old woman standing close beside her, who said:

‘My child, what have you done? Why didn’t you leave the flowers alone? They were your twelve brothers. Now they are changed for ever into ravens.’

The girl asked, sobbing: ‘Is there no means of setting them free?’

‘No,’ said the old woman, ‘there is only one way in the whole world, and that is so difficult that you won’t free them by it, for you would have to be dumb and not laugh for seven years, and if you spoke a single word, though but an hour were wanting to the time, your silence would all have been in vain, and that one word would slay your brothers.’

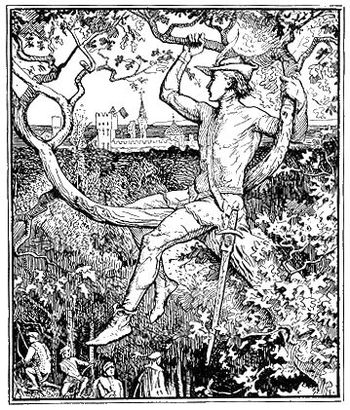

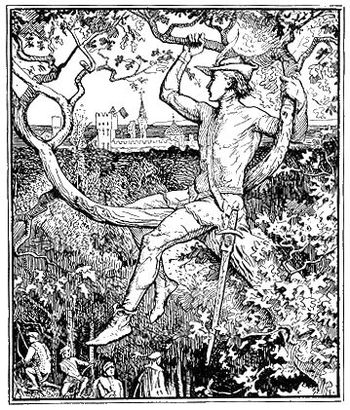

Then the girl said to herself: ‘If that is all I am quite sure I can free my brothers.’ So she searched for a high tree, and when she had found one she climbed up it and spun all day long, never laughing or speaking one word.

Now it happened one day that a King who was hunting in the wood had a large greyhound, who ran sniffing to the tree on which the girl sat, and jumped round it, yelping and barking furiously. The King’s attention was attracted, and when he looked up and beheld the beautiful Princess with the golden star on her forehead, he was so enchanted by her beauty that he asked her on the spot to be his wife. She gave no answer, but nodded slightly with her head. Then he climbed up the tree himself, lifted her down, put her on his horse and bore her home to his palace.

The marriage was celebrated with much pomp and ceremony, but the bride neither spoke nor laughed.

When they had lived a few years happily together, the King’s mother, who was a wicked old woman, began to slander the young Queen, and said to the King:

‘She is only a low-born beggar maid that you have married; who knows what mischief she is up to? If she is deaf and can’t speak, she might at least laugh; depend upon it, those who don’t laugh have a bad conscience.’ At first the King paid no heed to her words, but the old woman harped so long on the subject, and accused the young Queen of so many bad things, that at last he let himself be talked over, and condemned his beautiful wife to death.

So a great fire was lit in the courtyard of the palace, where she was to be burnt, and the King watched the proceedings from an upper window, crying bitterly the while, for he still loved his wife dearly. But just as she had been bound to the stake, and the flames were licking her garments with their red tongues, the very last moment of the seven years had come. Then a sudden rushing sound was heard in the air, and twelve ravens were seen flying overhead. They swooped downwards, and as soon as they touched the ground they turned into her twelve brothers, and she knew that she had freed them.

They quenched the flames and put out the fire, and, unbinding their dear sister from the stake, they kissed and hugged her again and again. And now that she was able to open her mouth and speak, she told the King why she had been dumb and not able to laugh.

The King rejoiced greatly when he heard she was innocent, and they all lived happily ever afterwards.

Grimm.

I dodici fratelli

C’erano una volta un re e una regina che vivevano felici insieme e avevano dodici figli, i quali erano tutti maschi. Un giorno il re disse alla moglie:

“Se il nostro tredicesimo figlio sarà una bambina, tutti i dodici fratelli dovranno morire, così che lei possa essere assai ricca e il regno sia solo suo.”

Poi ordinò che fossero costruite dodici bare, riempite di trucioli e in ciascuna fosse collocato un cuscino. Le fece mettere in una stanza vuota e, dando la chiave alla moglie, le disse di non parlarne con nessuno.

La regina si affliggeva per il triste destino dei figli e rifiutava così tanto ogni consolazione che il figlio più giovane, il quale stava sempre con lei e che aveva battezzato Beniamino, un giorno le disse:

“Madre cara, perché sei così triste?”

“Figlio mio,” rispose, “non posso dirtene la ragione.”

Ma lui non la lasciò in pace finché lei andò ad aprire la stanza e gli mostrò le dodici bare riempite di trucioli e con un piccolo cuscino in ciascuna.

Poi disse: “Mio caro Beniamino, tuo padre ha fatto fare queste bare per te e per i tuoi undici fratelli perché se io dovessi mai avere una figlia, voi sareste tutti uccisi e chiusi in esse.”

Piangeva amaramente mentre parlava, ma il figlio la consolò e disse:

“Non piangere, madre cara; riusciremo a scamparla in qualche modo e salveremo le nostre vite.”

“Sì,” rispose la madre, “ ecco ciò che dovete fare: va nel bosco con i tuoi undici fratelli e fate in modo che uno di voi stia sempre seduto sull’albero più alto che possiate trovare, tenendo d’occhio la torre del castello. Se avrò un un bambino, esporrò una bandiera bianca e allora voi potrete tornare sani e salvi, ma se avrò una bambina, esporrò una bandiera rossa che vi avvertirà di fuggire più in fretta che potrete e possa il cielo avere compassione di voi. Ogni notte mi alzerò e pregherò per voi, che in inverno possiate sempre avere un fuoco per scaldarvi e in estate non possiate languire per il caldo.”

Poi benedisse i figli e loro andarono nel bosco. Trovarono una quercia molto alta e sedettero lì a turno, tenendo gli occhi sempre fissi sulla torre del castello. Il dodicesimo giorno, quando fu il turno di beniamino, notò una bandiera che sventolava nell’aria, ma, ahimè, non era bianca bensì rosso sangue, il segnale che diceva loro di dover morire tutti. Quando i fratelli lo sentirono, si arrabbiarono molto e dissero:

“Dovremo subire la morte per il bene di una dannata ragazza? Giuriamo vendetta e che dovunque e ogni volta in cui incontreremo una del suo sesso, la uccideremo con le nostre mani.”

Poi si addentrano nel bosco e nel mezzo, dove era più folto e oscuro, giunsero a una casetta incantata che trovarono vuota.

“Qui prenderemo dimora,” dissero “e tu, beniamino, che sei il più giovane e debole, resterai in casa e vi baderai per noi, che andremo a procurare il cibo.” Così andarono nel bosco e spararono alle lepri e ai caprioli, agli uccelli a i piccioni, e a ogni altra preda che incontrassero. Portarono sempre le spoglie a casa a Beniamino, il quale ben presto imparò a trasformarle in squisite pietanze. Vissero così per dieci anni nella casetta e il tempo trascorreva allegramente.

Nel frattempo a casa la loro sorellina cresceva rapidamente. Era buona e di bell’aspetto e aveva una stella d’oro proprio in mezzo alla fronte. Un giorno fu fatto un grosso bucato a corte e la ragazza, guardando fuori dalla finestra, vide dodici camicie da uomo appese ad asciugare e chiese alla madre:

“A chi mai appartengono quelle camicie? Sicuramente sono troppo piccolo per mio padre.”

E la regina rispose tristemente: “Bambina cara, appartengono ai tuoi dodici fratelli.”

“Ma dove sono i miei dodici fratelli?” chiese la ragazza. “Non ho mai sentito parlare di loro.”

“Il cielo sa in quale parte del vasto mondo stiano vagando.” rispose la madre.

Poi prese la ragazza e aprì la stanza chiusa a chiave; le mostrò le dodici bare piene di trucioli e con un piccolo cuscino in ciascuna.

“Queste bare,” disse, “furono volute per i tuoi fratelli, ma loro sono fuggiti via in segreto prima della tua nascita.”

Poi le raccontò tutto ciò che era accaduto e, quando ebbe finito, la figlia disse:

“Non piangere, madre carissima, andrò a cercare i miei fratelli finché li troverò.”

Così prese le dodici camicie e andò nel cuore del grande bosco. Camminò per tutto il giorno e la sera giunse alla casetta incantata. Vi si fermò e trovò un ragazzo il quale, stupito per la sua bellezza, per l’abbigliamento regale che indossava e per la stella d’oro sulla fronte, le chiese da dove venisse e dove stesse andando.

“Sono una principessa” rispose “ e sto cercando i miei dodici fratelli. Intendo camminare dove il cielo blu si stende oltre la terra finché li avrò trovati.”

Poi gli mostrò le dodici camicie che aveva portato con sé e Beniamino vide che quella doveva essere la loro sorella e disse:

“Sono Beniamino, il tuo fratello più giovane.”

Così piansero di gioia e si baciarono e abbracciarono l’un l’altra ancora e ancora. Dopo un po’ di tempo Beniamino disse:

“Sorella cara, c’è ancora una piccola difficoltà perché abbiamo giurato tutti che qualsiasi ragazza avessimo incontrato, sarebbe morta per mano nostra perché è stato a causa di una ragazza che abbiamo dovuto lasciare il nostro regno.”

“Lei rispose: “Ma io morirò volentieri se significa che posso salvare i miei dodici fratelli.”

“No, non è necessario;” rispose lui. “solo vai a nasconderti sotto quel mastello finché saranno tornati in miei undici fratelli e io farò intender loro ragione.”

Così fece come le era stato detto e ben presto gli altri tornarono dalla caccia e sedettero a cena.

“Ebbene, Beniamino, che novità ci sono?” chiesero. Ma lui rispose: “Mi fa piacere, non avete nulla da dirmi voi?”

“No.” risposero loro.

Allora disse: “Ebbene, voi siete stati nel bosco per tutto il giorno e io sono rimasto tranquillo a casa eppure ne so più di voi.”

“Allora raccontaci.” esclamarono.

Ma lui rispose: “Solo a condizione che promettiate solennemente che la prima ragazza che incontreremo non verrà uccisa.”

“La risparmieremo,” promisero, “basta che ci racconti la novità.”

Allora Beniamino disse: “Nostra sorella è qui!” e sollevò il mastello e la principessa venne fuori, nel suo abbigliamento regale e con la stella d’oro sulla fronte, mostrandosi così bella e dolce e affascinante che tutti l’amarono subito.

Concordarono che sarebbe rimasta a casa con Beniamino e lo avrebbe aiutato nei lavori di casa mentre gli altri fratelli andavano nel bosco a cacciare lepri e caprioli, uccelli e piccioni. Beniamino e la sorella cucinavano i pasti per loro. Raccoglievano erbe aromatiche per cuocervi le verdure, andavano a prendere la legna e sorvegliavano la pentola sul fuoco e, quando gli undici fratelli tornavano, la cena era sempre pronta per loro. Oltre a ciò, lei teneva in ordine la casa, rassettava tutte le stanze e si rendeva così utile che i fratelli erano contentissimi e vivevano tutti insieme felicemente.

Un giorno i due a casa prepararono un bel banchetto e, quando furono tutti riuniti, sedettero a mangiare e bere allegramente.

c’era un giardinetto intorno alla casetta incantata, nel quale crescevano dodici alti gigli. La ragazza, desiderosa di compiacere i fratelli, raccolse i dodici fiori con l’intenzione di offrirli a ognuno di loro quando sarebbero stati seduti a cena. Ma li aveva appena colto i fiori che i suoi fratelli furono trasformati in dodici corvi, che volarono nel bosco gracchiando e svanirono anche la casa e il giardino.

Così la povera ragazza si ritrovò sola nel bosco e, mentre si guardava attorno, si accorse di una vecchietta accanto a lei che disse:

“Bambina mia, che cosa hai fatto? Perché non hai lasciato stare i fiori? Erano i tuoi fratelli e adesso si sono tramutati per sempre in corvi.”

Singhiozzando, la ragazza chiese: “Non c’è un modo per liberarli?”

“No,” disse la vecchia, “c’è solo una maniera al mondo ed è così ardua che tu non potrai liberarli perché dovresti restare mura e senza ridere per sette anni, e se solo pronuncerai una singola parola, seppur mancasse solo un’ora allo scadere del tempo, il tuo silenzio sarebbe stato vano e quell’unica parola ucciderebbe i tuoi fratelli.”

Allora la ragazza disse tra sé:’Se è tutto qui, sono certa di poter liberare i miei fratelli.’ così cercò un albero alto e, quando l’ebbe trovato, vi si arrampicò e filò per tutto il giorno, senza ridere o pronunciare una parola.

Capitò che un giorno un re che stava andando a caccia nel bosco avesse un grosso levriero il quale corse ad annusare l’albero sul quale sedeva la ragazza e vi saltellò attorno, latrando e abbaiando furiosamente. l’attenzione del re fu attirata e quando guardò in su e vide la splendida principessa con la stella d’oro in fronte, fu subito rapito dalla sua bellezza e le chiese all’istante di sposarlo. Lei non rispose, ma fece cenno leggermente con la testa. Allora lui si arrampicò, la fece scendere, la mise in sella e la condusse nel proprio palazzo.

Le nozze furono celebrate con grande fasto e pompa, ma la sposa non parlava e non rideva.

Dopo che ebbero vissuto felicemente insieme per alcuni anni, la madre del re, che era una vecchia malvagia, cominciò a calunniare la giovane regina e disse al re:

“È solo una povera ragazza di bassa estrazione che hai sposato; chi può sapere che male abbia combinato? Se è sorda e non può parlare, potrebbe almeno ridere; dipende da ciò, chi non ride ha la coscienza sporca.” dapprima il re non badò alle sue parole, ma la vecchia regina insisteva tanto sull’argomento e accusava la giovane regina di chissà quali cattiverie che alla fine egli cambiò idea e condannò a morte la sua bellissima moglie.

Così nel cortile del castello fu preparato un grande rogo nel quale sarebbe stata bruciata e il re guardava l’esecuzione da una finestra del piano superiore, piangendo amaramente ciò che avveniva perché amava teneramente la moglie. Ma proprio mentre era stata legata al palo e le fiamme avevano cominciato a lambirle i vestiti con le loro lingue rosse, proprio in quel momento si compirono i sette anni. All’improvviso si sentì un fruscio nell’aria e si videro dodici corvi volare lì sopra. Scesero in picchiata e, appena toccarono il suolo, si trasformarono nei dodici fratelli e lei seppe di averli liberati.

Spensero le fiamme e il fuoco e, liberando dal palo la loro cara sorella, si abbracciarono e si baciarono ancora e ancora. E adesso che poteva aprire la bocca e parlare, raccontò al re perché fosse stata muta e senza ridere.

Il re fu assai contento di sentire che fosse innocente e poi vissero tutti felici e contenti.

Fratelli Grimm

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)