The half chick

(MP3-4,0MB;08'26'')

Once upon a time there was a handsome black Spanish hen, who had a large brood of chickens. They were all fine, plump little birds, except the youngest, who was quite unlike his brothers and sisters. Indeed, he was such a strange, queer-looking creature, that when he first chipped his shell his mother could scarcely believe her eyes, he was so different from the twelve other fluffy, downy, soft little chicks who nestled under her wings. This one looked just as if he had been cut in two. He had only one leg, and one wing, and one eye, and he had half a head and half a beak. His mother shook her head sadly as she looked at him and said:

'My youngest born is only a half-chick. He can never grow up a tall handsome cock like his brothers. They will go out into the world and rule over poultry yards of their own; but this poor little fellow will always have to stay at home with his mother.' And she called him Medio Pollito, which is Spanish for half-chick.

Now though Medio Pollito was such an odd, helpless-looking little thing, his mother soon found that he was not at all willing to remain under her wing and protection. Indeed, in character he was as unlike his brothers and sisters as he was in appearance. They were good, obedient chickens, and when the old hen chicked after them, they chirped and ran back to her side. But Medio Pollito had a roving spirit in spite of his one leg, and when his mother called to him to return to the coop, he pretended that he could not hear, because he had only one ear.

When she took the whole family out for a walk in the fields, Medio Pollito would hop away by himself, and hide among the Indian corn. Many an anxious minute his brothers and sisters had looking for him, while his mother ran to and fro cackling in fear and dismay.

As he grew older he became more self-willed and disobedient, and his manner to his mother was often very rude, and his temper to the other chickens very disagreeable.

One day he had been out for a longer expedition than usual in the fields. On his return he strutted up to his mother with the peculiar little hop and kick which was his way of walking, and cocking his one eye at her in a very bold way he said:

'Mother, I am tired of this life in a dull farmyard, with nothing but a dreary maize field to look at. I'm off to Madrid to see the King.'

'To Madrid, Medio Pollito!' exclaimed his mother; 'why, you silly chick, it would be a long journey for a grown-up cock, and a poor little thing like you would be tired out before you had gone half the distance. No, no, stay at home with your mother, and some day, when you are bigger, we will go a little journey together.'

But Medio Pollito had made up his mind, and he would not listen to his mother's advice, nor to the prayers and entreaties of his brothers and sisters.

'What is the use of our all crowding each other up in this poky little place?' he said. 'When I have a fine courtyard of my own at the King's palace, I shall perhaps ask some of you to come and pay me a short visit,' and scarcely waiting to say good-bye to his family, away he stumped down the high road that led to Madrid.

'Be sure that you are kind and civil to everyone you meet,' called his mother, running after him; but he was in such a hurry to be off, that he did not wait to answer her, or even to look back.

A little later in the day, as he was taking a short cut through a field, he passed a stream. Now the stream was all choked up, and overgrown with weeds and water-plants, so that its waters could not flow freely.

'Oh! Medio Pollito,' it cried, as the half-chick hopped along its banks, 'do come and help me by clearing away these weeds.'

'Help you, indeed!' exclaimed Medio Pollito, tossing his head, and shaking the few feathers in his tail. 'Do you think I have nothing to do but to waste my time on such trifles? Help yourself, and don't trouble busy travellers. I am off to Madrid to see the King,' and hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick, away stumped Medio Pollito.

A little later he came to a fire that had been left by some gipsies in a wood. It was burning very low, and would soon be out.

'Oh! Medio Pollito,' cried the fire, in a weak, wavering voice as the half-chick approached, 'in a few minutes I shall go quite out, unless you put some sticks and dry leaves upon me. Do help me, or I shall die!'

'Help you, indeed!' answered Medio Pollito. 'I have other things to do. Gather sticks for yourself, and don't trouble me. I am off to Madrid to see the King,' and hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick, away stumped Medio Pollito.

The next morning, as he was getting near Madrid, he passed a large chestnut tree, in whose branches the wind was caught and entangled. 'Oh! Medio Pollito,' called the wind, 'do hop up here, and help me to get free of these branches. I cannot come away, and it is so uncomfortable.'

'It is your own fault for going there,' answered Medio Pollito. 'I can't waste all my morning stopping here to help you. Just shake yourself off, and don't hinder me, for I am off to Madrid to see the King,' and hoppity-kick, hoppity-kick, away stumped Medio Pollito in great glee, for the towers and roofs of Madrid were now in sight. When he entered the town he saw before him a great splendid house, with soldiers standing before the gates. This he knew must be the King's palace, and he determined to hop up to the front gate and wait there until the King came out. But as he was hopping past one of the back windows the King's cook saw him:

'Here is the very thing I want,' he exclaimed, 'for the King has just sent a message to say that he must have chicken broth for his dinner,' and opening the window he stretched out his arm, caught Medio Pollito, and popped him into the broth-pot that was standing near the fire. Oh! how wet and clammy the water felt as it went over Medio Pollito's head, making his feathers cling to his side.

'Water, water!' he cried in his despair, 'do have pity upon me and do not wet me like this.'

'Ah! Medio Pollito,' replied the water, 'you would not help me when I was a little stream away on the fields, now you must be punished.'

Then the fire began to burn and scald Medio Pollito, and he danced and hopped from one side of the pot to the other, trying to get away from the heat, and crying out in:

'Fire, fire! do not scorch me like this; you can't think how it hurts.'

'Ah! Medio Pollito,' answered the fire, 'you would not help me when I was dying away in the wood. You are being punished.'

At last, just when the pain was so great that Medio Pollito thought he must die, the cook lifted up the lid of the pot to see if the broth was ready for the King's dinner.

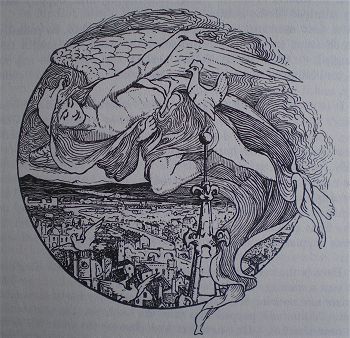

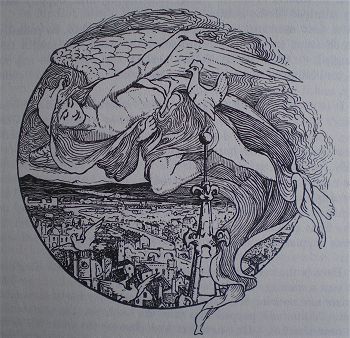

'Look here!' he cried in horror, 'this chicken is quite useless. It is burnt to a cinder. I can't send it up to the royal table;' and opening the window he threw Medio Pollito out into the street. But the wind caught him up, and whirled him through the air so quickly that Medio Pollito could scarcely breathe, and his heart beat against his side till he thought it would break.

'Oh, wind!' at last he gasped out, 'if you hurry me along like this you will kill me. Do let me rest a moment, or—' but he was so breathless that he could not finish his sentence.

'Ah! Medio Pollito,' replied the wind, 'when I was caught in the branches of the chestnut tree you would not help me; now you are punished.' And he swirled Medio Pollito over the roofs of the houses till they reached the highest church in the town, and there he left him fastened to the top of the steeple.

And there stands Medio Pollito to this day. And if you go to Madrid, and walk through the streets till you come to the highest church, you will see Medio Pollito perched on his one leg on the steeple, with his one wing drooping at his side, and gazing sadly out of his one eye over the town.

Spanish Tradition.

Il mezzo pulcino

C'era una volta una bella gallina nera spagnola che aveva una numerosa covata di pulcini. Erano tutti belli e in carne tranne il più piccolo, che era abbastanza diverso dai fratelli e dalle sorelle. Infatti era una creatura strana e bizzarra a vedersi, tanto che quando uscì dal guscio, sua madre quasi non credette ai propri occhi, poiché era così diverso dagli altri dodici soffici, lanuginosi pulcini che si rannicchiavano sotto le sue ali. Sembrava che fosse stato tagliato in due. Aveva solo una zampa, solo un'ala e solo un occhio, e aveva mezza testa e mezzo becco. La madre scosse tristemente la testa, lo guardò e disse:

"Il mio ultimogenito è solo un mezzo pulcino. Non diventerà mai un gallo bello e imponente come i suoi fratelli. Essi andranno per il mondo e domineranno il resto del pollame da cortile, ma questa povera creatura resterà sempre a casa con sua madre." E lo chiamò Medio Pollito, che in spagnolo significa mezzo pulcino.

Benché Medio Pollito fosse abbastanza strano, un cosino bisognoso di aiuto, sua madre si rese conto assai presto che non era disposto a rimanere sotto le sue ali e la sua protezione. Infatti, era diverso di carattere dai fratelli e dalle sorelle proprio come sembrava. Essi erano polli buoni e obbedienti, e quando la vecchia gallina chiocciava, tornavano pigolando accanto a lei. Ma Medio Pollito aveva un temperamento errabondo, a dispetto della sua unica zampa, e quando sua madre lo chiamava perché tornasse alla stia, fingeva di non sentirla perché aveva un solo orecchio.

Quando conduceva l'intera famigliola a passeggio per i campi, Medio Pollito voleva saltellare via da solo e nascondersi in mezzo al granturco. I fratelli e le sorelle lo cercavano per alcuni concitati momenti mentre la madre correva avanti e indietro impaurita e costernata.

Appena fu cresciuto, divenne ancor più indipendente e disubbidiente, le sue maniere verso la madre erano spesso assai maleducate e molto sgradevole la sua irascibilità nei confronti degli altri pulcini.

Un giorno se ne andò per una spedizione tra i campi più lunga del solito. Al ritorno camminò impettito dalla madre col tipico salta e scalcia del suo modo di camminare e, fissandola audacemente con l'unico occhio, disse:

"Madre, sono stanco di vivere in una noiosa cascina, con niente altro che deprimenti campi di mais da vedere. Me ne vado a Madrid a vedere il re."

"A Madrid, Medio Pollito!" esclamò sua madre, "Perché, pulcino sciocco, vorresti affrontare un viaggio lungo anche per un gallo, quando una cosina come te si stancherebbe prima di aver percorso anche solo metà della distanza. No, no, resta a casa con tua madre e un giorno, quando sarai più grande, faremo un viaggetto insieme."

Ma Medio Pollito aveva deciso e non volle ascoltare gli avvertimenti della madre né le preghiere e le suppliche dei fratelli e delle sorelle.

"Che vantaggio c'è ad affollarci tutti in questo angusto posticino?" disse. "Quando avrò un bel cortile solo per me al palazzo del re, forse dirò a qualcuno di voi di venire e pagarmi un breve soggiorno." E dicendo a malapena arrivederci alla sua famiglia, arrancò via lungo la strada che conduceva a Madrid.

"Bada di essere sempre gentile e educato con chi incontrerai," gridò sua madre, correndogli dietro; ma aveva tanta fretta di andarsene che non le rispose, né guardò indietro.

Un poco più tardi, mentre stava prendendo una scorciatoia attraverso un campo, oltrepassò un ruscello. Il ruscello era soffocato e invaso da erbacce e piante acquatiche, tanto che l'acqua non poteva scorrere liberamente.

"Oh, Medio Pollito," gridò il ruscello, appena il mezzo pulcino apparve sulla riva, "vieni e aiutami a ripulirmi da queste erbacce."

"Aiutarti, davvero!" esclamò Medio Pollito, girando la testa e scrollando le scarse piume della coda. "Pensi che non abbia di meglio da fare che sprecare il mio tempo in simili inezie? Aiutati da solo e non seccare i viaggiatori. Vado a Madrid a vedere il re." E, passetto passetto, Medio Pollito arrancò via.

Un po' più tardi giunse a un falò che era stato lasciato nel bosco dagli zingari. Stava bruciando assai lentamente e presto si sarebbe spento. "Oh, Medio Pollito," gridò il fuoco, con voce debole e incerta quando il mezzo pulcino si avvicinò, "in pochi minuti mi spegnerò, a meno che tu mi alimenti con rametti e foglie secche. Aiutami o morirò!"

"Aiutarti, davvero!" rispose Medio Pollito. "Ho altro da fare. Raccogli da solo i rametti e non seccarmi. Vado a Madrid a vedere il re." E, passetto passetto, Medio Pollito arrancò via.

La mattina successiva, quando era quasi vicino a Madrid, oltrepassò un grande castagno, tra i cui rami il vento era rimasto impigliato. "Oh, Medio Pollito," chiamò il vento, "salta su e aiutami a liberarmi dai rami. Non posso andar via, è così scomodo."

"È un tuo problema andartene da qui," rispose Medio Pollito. "Non posso perdere tutta la mattina trattenendomi qui ad aiutarti. Datti una scrollata e non intralciarmi, perché vado a Madrid a vedere il re." E, passetto passetto, Medio Pollito arrancò via allegramente, perché le torri e i tetti di Madrid erano in vista. Quando entrò in città, si trovò davanti un'enorme e splendida casa, davanti ai cui cancelli stavano dei soldati. Ritenne che fosse il palazzo del re e decise di saltare il cancello anteriore e aspettare che arrivasse il re. Ma appena ebbe saltato, dietro una delle finestre posteriori, il cuoco del re lo vide:

"Ecco ciò che mi occorre," esclamò, "perché il re ha appena mandato un messaggio per dire che vuole brodo di pollo a cena," e, aprendo la finestra, allungò un braccio, afferrò Medio Pollito e lo scaraventò nella pentola che stava vicino al fuoco. Oh! Com'era bagnata e calda l'acqua che piovve sulla testa di Medio Pollito, appiccicandogli addosso le piume.

"Acqua, acqua!" gridò disperato, "abbi pietà di me e non bagnarmi così."

"Ah, Medio Pollito," replicò l'acqua, "non hai voluto aiutarmi quando ero un ruscelletto nei campi, ora devi essere punito."

Poi il fuoco incominciò a bruciare e a scottare Medio Pollito, e lui si muoveva e saltellava da un lato all'altro della pentola, tentando di sfuggire al calore, e gridando di dolore:

"Fuoco, fuoco! Non bruciarmi così; non hai idea di quanto faccia male."

"Ah, Medio Pollito," rispose il fuoco, "non hai voluto aiutarmi quando stavo per spegnermi nel bosco. Devi essere punito."

Infine, quando il dolore fu tale che Medio Pollito pensò di star per morire, il cuoco sollevò il coperchio della pentola per vedere se il brodo fosse pronto per la cena del re.

"Guarda!" gridò orripilato, "questo pollo è quasi inservibile. È carbonizzato. Non posso servirlo alla mensa reale." E, aprendo la finestra, gettò Medio Pollito per strada. Ma il vento lo prese e lo trasportò nell'aria così velocemente che Medio Pollito poteva a malapena respirare, e il suo cuore batteva quasi fino a schiantarsi.

"Oh, vento!" esalò infine, "Se mi fai correre così, mi ucciderai. Fammi riposare un momento, o - " ma aveva così poco fiato che non poté finire la frase.

"Ah! Medio Pollito," replicò il vento, "Quando ero prigioniero tra i rami del Castagno, non hai voluto aiutarmi; adesso devi essere punito." E fece turbinare Medio Pollito oltre i tetti delle case finché raggiunse la più alta chiesa della città, e lì lo lasciò attaccato, in cima al campanile.

E lì è rimasto Medio Pollito, fino ai giorni nostri. Se andate a Madrid e camminate per le strade fino ad arrivare alla chiesa più grande, vedrete Medio Pollito appollaiato sulla sua unica zampa in cima al campanile, con l'unica ala che si posa al suo fianco, che fissa tristemente la città con il suo unico occhio.

Tradizione spagnola

Favola tradizionale spagnola che narra l'origine delle banderuole segnavento sui tetti e sui campanili (n.d.T.)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)