Little One-eye, Little Two-eyes and Little Three-eyes

(MP3-14'28'')

There was once a woman who had three daughters, of whom the eldest was called Little One-eye, because she had only one eye in the middle of her forehead; and the second, Little Two-eyes, because she had two eyes like other people; and the youngest, Little Three-eyes, because she had three eyes, and her third eye was also in the middle of her forehead. But because Little Two-eyes did not look any different from other children, her sisters and mother could not bear her. They would say to her, ‘You with your two eyes are no better than common folk; you don’t belong to us.’ They pushed her here, and threw her wretched clothes there, and gave her to eat only what they left, and they were as unkind to her as ever they could be.

It happened one day that Little Two-eyes had to go out into the fields to take care of the goat, but she was still quite hungry because her sisters had given her so little to eat. So she sat down in the meadow and began to cry, and she cried so much that two little brooks ran out of her eyes. But when she looked up once in her grief there stood a woman beside her who asked, ‘Little Two-eyes, what are you crying for?’ Little Two-eyes answered, ‘Have I not reason to cry? Because I have two eyes like other people, my sisters and my mother cannot bear me; they push me out of one corner into another, and give me nothing to eat except what they leave. To-day they have given me so little that I am still quite hungry.’ Then the wise woman said, ‘Little Two-eyes, dry your eyes, and I will tell you something so that you need never be hungry again. Only say to your goat,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, appear,”

and a beautifully spread table will stand before you, with the most delicious food on it, so that you can eat as much as you want. And when you have had enough and don’t want the little table any more, you have only to say,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, away,”

and then it will vanish.’ Then the wise woman went away.

But Little Two-eyes thought, ‘I must try at once if what she has told me is true, for I am more hungry than ever’; and she said,

‘Little goat, bleat, Little table appear,’

and scarcely had she uttered the words, when there stood a little table before her covered with a white cloth, on which were arranged a plate, with a knife and fork and a silver spoon, and the most beautiful dishes, which were smoking hot, as if they had just come out of the kitchen. Then Little Two-eyes said the shortest grace she knew, and set to work and made a good dinner. And when she had had enough, she said, as the wise woman had told her,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, away,”

and immediately the table and all that was on it disappeared again. ‘That is a splendid way of housekeeping,’ thought Little Two-eyes, and she was quite happy and contented.

In the evening, when she went home with her goat, she found a little earthenware dish with the food that her sisters had thrown to her, but she did not touch it. The next day she went out again with her goat, and left the few scraps which were given her. The first and second times her sisters did not notice this, but when it happened continually, they remarked it and said, ‘Something is the matter with Little Two-eyes, for she always leaves her food now, and she used to gobble up all that was given her. She must have found other means of getting food.’ So in order to get at the truth, Little One-eye was told to go out with Little Two-eyes when she drove the goat to pasture, and to notice particularly what she got there, and whether anyone brought her food and drink.

Now when Little Two-eyes was setting out, Little One-eye came up to her and said, ‘I will go into the field with you and see if you take good care of the goat, and if you drive him properly to get grass.’ But Little Two-eyes saw what Little One-eye had in her mind, and she drove the goat into the long grass and said, ‘Come, Little One-eye, we will sit down here, and I will sing you something.’

Little One-eye sat down, and as she was very much tired by the long walk to which she was not used, and by the hot day, and as Little Two-eyes went on singing.

‘Little One-eye, are you awake? Little One-eye, are you asleep?’

She shut her one eye and fell asleep. When Little Two-eyes saw that Little One-eye was asleep and could find out nothing, she said,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, appear,”

and sat down at her table and ate and drank as much as she wanted. Then she said again,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, away,”

and in the twinkling of an eye all had vanished.

Little Two-eyes then woke Little One-eye and said, ‘Little One-eye, you meant to watch, and, instead, you went to sleep; in the meantime the goat might have run far and wide. Come, we will go home.’ So they went home, and Little Two-eyes again left her little dish untouched, and Little One-eye could not tell her mother why she would not eat, and said as an excuse, ‘I was so sleepy out-of-doors.’

The next day the mother said to Little Three-eyes, ‘This time you shall go with Little Two-eyes and watch whether she eats anything out in the fields, and whether anyone brings her food and drink, for eat and drink she must secretly.’ So Little Three-eyes went to Little Two-eyes and said, ‘I will go with you and see if you take good care of the goat, and if you drive him properly to get grass.’ But little Two-eyes knew what Little Three-eyes had in her mind, and she drove the goat out into the tall grass and said, ‘We will sit down here, Little Three-eyes, and I will sing you something.’ Little Three-eyes sat down; she was tired by the walk and the hot day, and Little Two-eyes sang the same little song again:

‘Little Three eyes, are you awake?’

but instead of singing as she ought to have done,

‘Little Three-eyes, are you asleep?’

she sang, without thinking,

‘Little Two-eyes, are you asleep?’

She went on singing,

‘Little Three-eyes, are you awake? Little Two-eyes, are you asleep?’

so that the two eyes of Little Three-eyes fell asleep, but the third, which was not spoken to in the little rhyme, did not fall asleep. Of course Little Three-eyes shut that eye also out of cunning, to look as if she were asleep, but it was blinking and could see everything quite well.

And when Little Two-eyes thought that Little Three-eyes was sound asleep, she said her rhyme,

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, appear,”

and ate and drank to her heart’s content, and then made the table go away again, by saying,

‘Little goat, bleat, Little table, away.’

But Little Three-eyes had seen everything. Then Little Two-eyes came to her, and woke her and said, ‘Well, Little Three-eyes, have you been asleep? You watch well! Come, we will go home.’ When they reached home, Little Two-eyes did not eat again, and Little Three-eyes said to the mother, ‘I know now why that proud thing eats nothing. When she says to the goat in the field,

a table stands before her, spread with the best food, much better than we have; and when she has had enough, she says,

and everything disappears again. I saw it all exactly. She made two of my eyes go to sleep with a little rhyme, but the one in my forehead remained awake, luckily!’

Then the envious mother cried out, ‘Will you fare better than we do? you shall not have the chance to do so again!’ and she fetched a knife, and killed the goat.

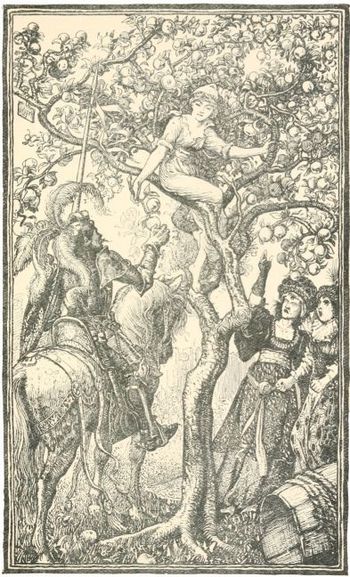

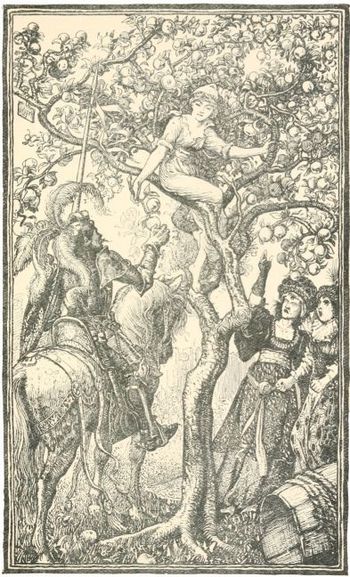

When Little Two-eyes saw this, she went out full of grief, and sat down in the meadow and wept bitter tears. Then again the wise woman stood before her, and said, ‘Little Two-eyes, what are you crying for?’ ‘Have I not reason to cry?’ she answered, ‘the goat, which when I said the little rhyme, spread the table so beautifully, my mother has killed, and now I must suffer hunger and want again.’ The wise woman said, ‘Little Two-eyes, I will give you a good piece of advice. Ask your sisters to give you the heart of the dead goat, and bury it in the earth before the house-door; that will bring you good luck.’ Then she disappeared, and Little Two-eyes went home, and said to her sisters, ‘Dear sisters, do give me something of my goat; I ask nothing better than its heart.’ Then they laughed and said, ‘You can have that if you want nothing more.’ And Little Two-eyes took the heart and buried it in the evening when all was quiet, as the wise woman had told her, before the house-door. The next morning when they all awoke and came to the house-door, there stood a most wonderful tree, which had leaves of silver and fruit of gold growing on it—you never saw anything more lovely and gorgeous in your life! But they did not know how the tree had grown up in the night; only Little Two-eyes knew that it had sprung from the heart of the goat, for it was standing just where she had buried it in the ground. Then the mother said to Little One-eye, ‘Climb up, my child, and break us off the fruit from the tree.’ Little One-eye climbed up, but just when she was going to take hold of one of the golden apples the bough sprang out of her hands; and this happened every time, so that she could not break off a single apple, however hard she tried. Then the mother said, ‘Little Three-eyes, do you climb up; you with your three eyes can see round better than Little One-eye.’ So Little One-eye slid down, and Little Three-eyes climbed up; but she was not any more successful; look round as she might, the golden apples bent themselves back. At last the mother got impatient and climbed up herself, but she was even less successful than Little One-eye and Little Three-eyes in catching hold of the fruit, and only grasped at the empty air. Then Little Two-eyes said, ‘I will just try once, perhaps I shall succeed better.’ The sisters called out, ‘You with your two eyes will no doubt succeed!’ But Little Two-eyes climbed up, and the golden apples did not jump away from her, but behaved quite properly, so that she could pluck them off, one after the other, and brought a whole apron-full down with her. The mother took them from her, and, instead of behaving better to poor Little Two-eyes, as they ought to have done, they were jealous that she only could reach the fruit and behaved still more unkindly to her.

It happened one day that when they were all standing together by the tree that a young knight came riding along. ‘Be quick, Little Two-eyes,’ cried the two sisters, ‘creep under this, so that you shall not disgrace us,’ and they put over poor Little Two-eyes as quickly as possible an empty cask, which was standing close to the tree, and they pushed the golden apples which she had broken off under with her. When the knight, who was a very handsome young man, rode up, he wondered to see the marvellous tree of gold and silver, and said to the two sisters, ‘Whose is this beautiful tree? Whoever will give me a twig of it shall have whatever she wants.’ Then Little One-eye and Little Three-eyes answered that the tree belonged to them, and that they would certainly break him off a twig. They gave themselves a great deal of trouble, but in vain; the twigs and fruit bent back every time from their hands. Then the knight said, ‘It is very strange that the tree should belong to you, and yet that you have not the power to break anything from it!’ But they would have that the tree was theirs; and while they were saying this, Little Two-eyes rolled a couple of golden apples from under the cask, so that they lay at the knight’s feet, for she was angry with Little One-eye and Little Three-eyes for not speaking the truth. When the knight saw the apples he was astonished, and asked where they came from. Little One-eye and Little Three-eyes answered that they had another sister, but she could not be seen because she had only two eyes, like ordinary people. But the knight demanded to see her, and called out, ‘Little Two-eyes, come forth.’ Then Little Two-eyes came out from under the cask quite happily, and the knight was astonished at her great beauty, and said, ‘Little Two-eyes, I am sure you can break me off a twig from the tree.’ ‘Yes,’ answered Little Two-eyes, ‘I can, for the tree is mine.’ So she climbed up and broke off a small branch with its silver leaves and golden fruit without any trouble, and gave it to the knight.

Then he said, ‘Little Two-eyes, what shall I give you for this?’ ‘Ah,’ answered Little Two-eyes, ‘I suffer hunger and thirst, want and sorrow, from early morning till late in the evening; if you would take me with you, and free me from this, I should be happy!’ Then the knight lifted Little Two-eyes on his horse, and took her home to his father’s castle. There he gave her beautiful clothes, and food and drink, and because he loved her so much he married her, and the wedding was celebrated with great joy.

When the handsome knight carried Little Two-eyes away with him, the two sisters envied her good luck at first. ‘But the wonderful tree is still with us, after all,’ they thought, ‘and although we cannot break any fruit from it, everyone will stop and look at it, and will come to us and praise it; who knows whether wemay not reap a harvest from it?’ But the next morning the tree had flown, and their hopes with it; and when Little Two-eyes looked out of her window there it stood underneath, to her great delight. Little Two-eyes lived happily for a long time. Once two poor women came to the castle to beg alms. Then Little Two-eyes looked at then and recognised both her sisters, Little One-eye and Little Three-eyes, who had become so poor that they came to beg bread at her door. But Little Two-eyes bade them welcome, and was so good to them that they both repented from their hearts of having been so unkind to their sister.

“Little goat, bleat, Little table, away,”

Grimm.

Unocchietto, Dueocchietti e Treocchietti

C’era una volta una donna che aveva tre figlie; la maggiore si chiamava Unochietto perché aveva un solo occhio in mezzo alla fronte, la seconda Dueocchietti perché aveva due occhi come tutte le altre persone e la più giovane Treocchietti perché aveva tre occhi e il terzo era in mezzo alla fronte. Siccome Dueocchietti non sembrava diversa dagli altri bambini, le sorelle e la madre non la sopportavano. E dicevano: “Tu con quei due occhi non sei meglio della gente comune, non fai parte di noi.” la spintonavano qua, le gettavano vestiti malandati là, le davano da mangiare solo gli avanzi ed erano sgarbate con lei quanto avrebbero potuto esserlo.

Un giorno Dueocchietti dovette andare nei campi a pascolare la capra, ma aveva tanta fame perché le sorelle le avevano dato così poco da mangiare. Così sedette nel prato e cominciò a piangere, e piangeva tanto che dagli occhi le scaturivano due ruscelletti. Mentre era così presa dai propri dispiaceri, guardò su e vide una donna accanto a lei che chiese: “Dueocchietti, perché stai piangendo?” Dueocchietti rispose: “Non ho forse ragione di piangere? Perché ho due occhi come le altre persone le mie sorelle e mia madre non possono sopportarmi; mi spingono da un angolo all’altro, non mi danno niente da mangiare se non avanzi. Oggi me ne hanno dati così pochi che ho tanta fame.” allora la donna saggia disse: “Dueocchietti, asciuga gli occhi e ti dirò qualcosa così che tu non debba mai più aver fame. Devi solo dire alla tua capra:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, compari.’

e una meravigliosa tavola sarà apparecchiata davanti a te con i cibi più deliziosi così che tu possa mangiare quanto vorrai. Quando ne avrai avuto abbastanza e non vorrai più il tavolino, dovrai solo dire:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, sparisci.’

e svanirà.” poi la donna saggia se ne andò.

Ma Dueocchietti pensò: ‘Devo provare subito se mi ha detto la verità perché ho più fame che mai.’e disse:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, compari.’

e aveva appena pronunciato le parole quando si vide davanti un tavolino con la tovaglia bianca sulla quale erano collocati un piatto con un coltello, una forchetta e un cucchiaio d’argento e i piatti più prelibati che fumavano, come se fossero stati appena usciti dalla cucina. Allora Dueocchietti pronunciò la più corta preghiera che conoscesse, poi si mise all’opera e fece un ottimo pasto. Quando ne ebbe abbastanza, disse come la donna saggia le aveva detto:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, sparisci.’

e immediatamente in tavolo e tutto ciò che vi era scomparve di nuovo. ‘Che splendido modo per governare la casa’ pensò Dueocchietti e fu felice e contenta.

La sera, quando tornò a casa con la capra, trovò un piattino di terraglia con il cibo che le sorelle le avevano gettato, ma non lo toccò. Il giorno successivo uscì di nuovo con la capra e tralasciò le poche briciole che le erano state date. La prima e la seconda volta le sorelle non se ne accorsero, ma quando accadde di continuo, lo notarono e dissero: “C’è qualcosa che non va con Dueocchietti perché adesso lascia sempre il cibo ed era solita trangugiare tutto ciò che le davamo. Deve aver trovato un altro modo per procurarsi il cibo.” Così, per scoprire la verità, a Unocchietto fu detto di andare con Dueocchietti quando portava la capra a pascolare e di osservare che cosa facesse là di particolare e se qualcuno le portasse da mangiare e da bere.

Così quando Dueocchietti stava andando, Unocchietto le si avvicinò e disse: “Verrò nel campo con te per vedere se ti prendi cura della capra e se la conduci come si deve a brucare.” Ma Dueocchietti sapeva che cosa avesse in mente Unocchietto e condusse la capra nell’erba alta e disse: “Vieni, Unocchietto, ci siederemo qui e io ti canterò qualcosa.”

Unocchietto sedette e siccome era molto stanca per la lunga camminata alla quale non era abituata e per il gran caldo e siccome Dueocchietti cominciò a cantare:

Unocchietto, sei sveglia? Unocchietto, stai dormendo?

lei chiuse gli occhi e si addormentò. Quando Dueocchietti vide che Unocchietto stava dormendo non avrebbe potuto accorgersi di niente, disse:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, compari.’

sedette al tavolo e mangiò e bevve quanto volle. Poi disse di nuovo:

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, sparisci.’

e in un batter d’occhio tutto sparì.

Dueocchietti allora svegliò, Unochietto e disse: “Unocchietto, volevi sorvegliarmi e invece ti sei messa a dormire; nel frattempo la capra è corsa in lungo e in largo. Andiamo, si torna a casa.” Così andarono a casa e di nuovo Dueocchietti lasciò intatto il suo piattino e Unocchietto non seppe dire alla madre perché non mangiasse e raccontò come scusa: “Ero così assonnata all’aperto.”

Il giorno seguente la madre disse a Treocchietti: “Stavolta sarai tu ad andare con Dueocchietti e a vedere se mangi nei campi e se qualcuno le porti cibo e bevande che lei mangia e beve di nascosto.” Cos’ Treocchietti andò da Dueocchietti e disse: “Verrò con te per vedere se ti prendi cura della capra e se la conduci come si deve a brucare l’erba.” ma Dueocchietti sapeva che cosa avesse in mente Treocchietti così condusse la capra in mezzo all’erba alta e disse “Ci siederemo qui, Treocchietti, e io ti canterò qualcosa.” Treocchietti sedette; era stanca per la camminata e per la giornata calda e Dueocchietti cantò di nuovo la medesima canzone:

Treocchietti, sei sveglia?

ma invece di cantare come avrebbe dovuto fare

Treocchietti, sei addormentata?

cantò senza rifletterci

Dueocchietti, sei addormentata?

E continuò a cantare

Treocchietti, sei sveglia? Dueocchietti sei addormentata?

così che due occhi di Treocchietti si chiusero nel sonno, ma il terzo, del quale non si era parlato nella filastrocca, non si chiuse nel sonno. Naturalmente Treocchietti chiuse quell’occhio solo per furbizia, per mostrare di essere addormentata, ma stava guardando con l’occhio socchiuso e poteva vedere tutto benissimo.

E quando Dueocchietti pensò che Treocchietti si fosse addormentata, pronunciò la filastrocca

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, compari.’

e mangiò e bevve a cuor contento, poi mandò via di nuovo il tavolino, dicendo

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, scompari.’

Ma Treocchietti aveva visto tutto. Quando Dueocchietti venne da lei, la svegliò e disse: “Ebbene, Treocchietti, hai dormito? Bella sorveglianza! Vieni, andiamo a casa.” Quando furono giunte a casa, Dueocchietti di nuovo non mangiò e Treocchietti disse alla madre: “Adesso so perché quella superbiosa non mangia niente. Quando dice alla capra nel campo

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, compari.’

davanti a lei compare un tavolo apparecchiato con i migliori cibi, molti più di quanti ne abbiamo noi, e quando ne ha abbastanza, dice

‘Capretta, bela, tavolino, scompari.’

e tutto sparisce di nuovo. L’ho visto perfettamente. Con una filastrocca mi ha fatto chiudere per il sonno due occhi, ma quello sulla fronte e rimasto sveglio, per fortuna!”

Allora la madre invidiosa gridò: “Vuoi passartela meglio di noi? Non avrai la possibilità di farlo ancora!” e, afferrato un coltello, uccise la capra.

Quando Dueocchietti vide ciò, fu molto addolorata e sedette nel prato a piangere lacrime amare. Allora la saggia donna fu di nuovo davanti a lei e disse. “Dueocchietti, perché stai piangendo?” “Non ho ragione di piangere?” rispose lei, “la capra, che quando pronunciavo la filastrocca mi apparecchiava così bene la tavola, è stata uccisa da mia madre e adesso io dovrò soffrire di nuovo la fame.” La donna saggia disse: “Dueocchietti, ti darò un buon consiglio. Chiedi alle tue sorelle di darti il cuore della capra morta e seppelliscilo nella terra davanti alla porta di casa; sarà la tua fortuna.” Poi sparì e Dueocchietti tornò a casa e disse alle sorelle: “Care sorelle, datemi qualcosa della mia capra; non chiede niente di più del cuore.” allora esse risero e dissero: “Lo puoi avere, se non chiederai niente altro.” E Dueocchietti prese il cuore e lo seppelì di sera, quando tutto era quieto, dvanati alla porta di casa come gli aveva detto la donna saggia. Il mattino seguente, quando tutte si svegliarono e si affacciarono alla porta di casa, lì sorgeva il più splendido degli alberi, sul quale erano cresciuti foglie d’argento e frutti d’oro, e non avete mai visto in vita vostra niente di più bello e splendido in vita vostra! Non sapevano come l’albero fosse cresciuto nella notte; solo Dueocchietti sapeva che fosse sorto dal cuore della capra perché si trovava proprio lì dove lo aveva sepolto nel terreno. Allora la madre disse a Unocchietto: “Arrampicati, bambina mia, e cogli un frutto dall’albero per noi.” Unocchietto si arrampicò, ma proprio quando stava per afferrare una delle mele d’oro, il ramo le sfuggì di mano e così accadde ogni volta, tanto che non poté cogliere una sola mela per quanto ci provasse tenacemente. Allora la madre disse: “Treocchietti, arrampicati tu; con i tuoi tre occhi puoi vedere meglio di Unocchietto.” Così Unocchietto scese e Treocchietti si arrampicò, ma non ebbe maggior successo; per quanto si guardasse attorno meglio che poteva, le mele d’oro continuavano a ritrarsi. Alla fine la madre diventò impaziente e si arrampicò lei stessa, ma ebbe perfino meno successo di Unocchieto e di Treocchietti nell’afferrare i frutti e abbrancava solo l’aria. Allora Dueocchietti disse: “Proverò anche io, forse mi andrà meglio.” Le sorelle esclamarono: “Con quei tuoi due occhi che cosa vuoi fare?” ma Dueocchietti si arrampicò e le mele d’oro non sia allontanarono da lei, ma si comportarono proprio bene così che lei poté coglierle, l’una dopo l’altra, e portare giù con sé l’intero grembiule pieno. La madre gliele prese e invece di trattare meglio la povera Dueocchietti, come avrebbero dovuto fare, erano gelose che solo lei riuscisse a cogliere i frutti si comportarono ancora più sgarbatamente con lei.

Un giorno accadde che, mentre stavano tutte insieme presso l’albero, un giovane cavaliere giungesse a cavallo. “Svelta, Dueocchietti,” strillarono le due sorelle, “nasconditi qui, così che non ci si debba vergognare di te.” e cacciarono la povera Dueocchietti più in fretta che poterono sotto una botte vuota che stava vicino all’albero e vi ficcarono sotto anche le mele che aveva raccolto. Quando il cavaliere, che era un giovane assai attraente, cavalcò fin lì, si meravigliò di vedere il meraviglioso albero d’oro e d’argento e disse alle due sorelle:” A chi appartiene questo magnifico albero? Chiunque me ne desse un ramo, potrebbe avere qualsiasi cosa voglia.” allora Unocchietto e Treocchietti risposero che l’albero apparteneva a loro e che certamente avrebbero spezzato un ramo per lui. Entrambe si diedero un gran da fare, ma invano; i rami e i frutti sfuggivano alle loro mani. Allora il cavaliere disse: “È molto strano che l’albero vi appartenga e voi non abbiate il potere di prendervi nulla!” E insistevano a dire che fosse loro, ma mentre lo stavano dicendo, Dueocchietti fece rotolare un paio di mele d’oro da sotto la botte così che giungessero ai piedi del cavaliere, perché era arrabbiata con Unocchietto e Treocchietti che non dicevano la verità. Quando il cavaliere vide le mele, rimase sbalordito e chiese da dove venissero. Unocchietto e Treocchietti risposero di avere un’altra sorella, ma che non la si poteva vedere perché aveva solo due occhi come la gente comune. Il cavaliere chiese di vederla e gridò: “Dueocchietti, vieni fuori.” Allora Dueocchietti uscì tutta contenta da sotto la botte e il cavaliere rimase stupefatto per la sua grande bellezza e disse: “Dueocchietti, sono sicuro che puoi spezzare per me un ramo dell’albero.” “Sì.” rispose Dueocchietti, “Posso farlo perché l’albero è mio.” Così si arrampicò e spezzò senza fatica un rametto con le foglie d’argento e i frutti d’oro e lo diede al cavaliere.

Allora lui disse: “Dueocchietti, che cosa posso darti per questo rametto?” E Dueocchietti rispose “Soffro fame e sete, povertà e dispiacere da mattina a sera; se vorrete portarmi via con voi e liberarmi da ciò, io sarò felice!” allora il cavaliere fece montare a cavallo Dueocchietti e la portò a casa, al castello di suo padre. Poi le diede abiti meravigliosi, cibo e bevande e, siccome l’amava tanto, la sposò e le nozze furono celebrate con grande gioia. Quando il bel cavaliere aveva portato via con sé Dueocchietti, le due sorelle dapprima invidiarono la sua fortuna. ‘Ma l’albero meraviglioso è ancora qui con noi dopotutto,’ pensarono ‘e sebbene non possiamo staccare alcun frutto, chiunque si fermerà qui a guardarlo e verrà da noi a lodarlo; chissà che noi non si possa ricavare un vantaggio?’ ma il mattino seguente l’albero era scomparso e le loro speranze svanite con esso; quando Dueocchietti guardò fuori dalla finestra, esso stava lì sotto, con sua grande gioia. Dueocchietti visse a lungo felicemente. Una volta due povere donne vennero al castello a chiedere l’elemosina, allora Dueocchietti le guardò e riconobbe entrambe le sorelle, Unocchietto e Treocchietti, che erano diventate così povere da dover andare a mendicare il pane alla sua porta. Dueocchietti diede loro il benvenuto e fu così buona che entrambe si pentirono sinceramente di esser state così cattive con la loro sorella.

Fratelli Grimm

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)