The finest liar in the world

At the edge of a wood there lived an old man who had only one son, and one day he called the boy to him and said he wanted some corn ground, but the youth must be sure never to enter any mill where the miller was beardless.

The boy took the corn and set out, and before he had gone very far he saw a large mill in front of him, with a beardless man standing in the doorway.

'Good greeting, beardless one!' cried he.

'Good greeting, sonny,' replied the man.

'Could I grind something here?'

'Yes, certainly! I will finish what I am doing and then you can grind as long as you like.'

But suddenly the boy remembered what his father had told him, and bade farewell to the man, and went further down the river, till he came to another mill, not knowing that as soon as his back was turned the beardless man had picked up a bag of corn and run hastily to the same mill before him. When the boy reached the second mill, and saw a second beardless man sitting there, he did not stop, and walked on till he came to a third mill. But this time also the beardless man had been too clever for him, and had arrived first by another road. When it happened a fourth time the boy grew cross, and said to himself, 'It is no good going on; there seems to be a beardless man in every mill'; and he took his sack from his back, and made up his mind to grind his corn where he was.

The beardless man finished grinding his own corn, and when he had done he said to the boy, who was beginning to grind his, 'Suppose, sonny, we make a cake of what you have there.'

Now the boy had been rather uneasy when he recollected his father's words, but he thought to himself, 'What is done cannot be undone,' and answered, 'Very well, so let it be.'

Then the beardless one got up, threw the flour into the tub, and made a hole in the middle, telling the boy to fetch some water from the river in his two hands, to mix the cake. When the cake was ready for baking they put it on the fire, and covered it with hot ashes, till it was cooked through. Then they leaned it up against the wall, for it was too big to go into a cupboard, and the beardless one said to the boy:

'Look here, sonny: if we share this cake we shall neither of us have enough. Let us see who can tell the biggest lie, and the one who lies the best shall have the whole cake.'

The boy, not knowing what else to do, answered, 'All right; you begin.'

So the beardless one began to lie with all his might, and when he was tired of inventing new lies the boy said to him, 'My good fellow, if THAT is all you can do it is not much! Listen to me, and I will tell you a true story.

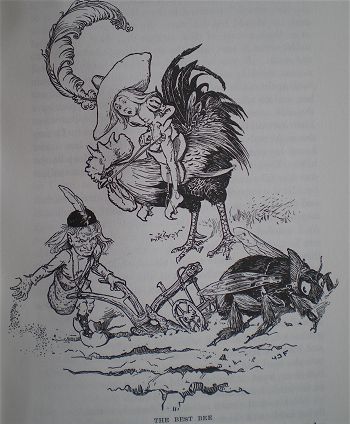

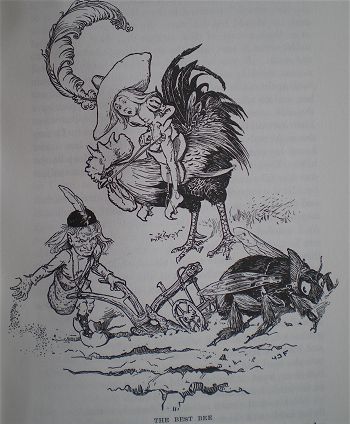

'In my youth, when I was an old man, we had a quantity of beehives. Every morning when I got up I counted them over, and it was quite easy to number the bees, but I never could reckon the hives properly. One day, as I was counting the bees, I discovered that my best bee was missing, and without losing a moment I saddled a cock and went out to look for him. I traced him as far as the shore, and knew that he had crossed the sea, and that I must follow. When I had reached the other side I found a man had harnessed my bee to a plough, and with his help was sowing millet seed.

'"That is my bee!" I shouted. "Where did you get him from?"'

"Brother," replied the man, "if he is yours, take him." And he not only gave me back my bee, but a sack of millet seed into the bargain, because he had made use of my bee. Then I put the bag on my shoulders, took the saddle from the cock, and placed it on the back of the bee, which I mounted, leading the cock by a string, so that he should have a rest. As we were flying home over the sea one of the strings that held the bag of millet broke in two, and the sack dropped straight into the ocean. It was quite lost, of course, and there was no use thinking about it, and by the time we were safe back again night had come. I then got down from my bee, and let him loose, that he might get his supper, gave the cock some hay, and went to sleep myself. But when I awoke with the sun what a scene met my eyes! During the night wolves had come and had eaten my bee. And honey lay ankle-deep in the valley and knee-deep on the hills. Then I began to consider how I could best collect some, to take home with me. 'Now it happened that I had with me a small hatchet, and this I took to the wood, hoping to meet some animal which I could kill, whose skin I might turn into a bag. As I entered the forest I saw two roe-deer hopping on one foot, so I slew them with a single blow, and made three bags from their skins, all of which I filled with honey and placed on the back of the cock. At length I reached home, where I was told that my father had just been born, and that I must go at once to fetch some holy water to sprinkle him with. As I went I turned over in my mind if there was no way for me to get back my millet seed, which had dropped into the sea, and when I arrived at the place with the holy water I saw the seed had fallen on fruitful soil, and was growing before my eyes. And more than that, it was even cut by an invisible hand, and made into a cake. 'So I took the cake as well as the holy water, and was flying back with them over the sea, when there fell a great rain, and the sea was swollen, and swept away my millet cake. Ah, how vexed I was at its loss when I was safe on earth again. 'Suddenly I remembered that my hair was very long. If I stood it touched the ground, although if I was sitting it only reached my ears. I seized a knife and cut off a large lock, which I plaited together, and when night came tied it into a knot, and prepared to use it for a pillow. But what was I to do for a fire? A tinder box I had, but no wood. Then it occurred to me that I had stuck a needle in my clothes, so I took the needle and split it in pieces, and lit it, then laid myself down by the fire and went to sleep. But ill-luck still pursued me. While I was sleeping a spark from the fire lighted on the hair, which was burnt up in a moment. In despair I threw myself on the ground, and instantly sank in it as far as my waist. I struggled to get out, but only fell in further; so I ran to the house, seized a spade, dug myself out, and took home the holy water. On the way I noticed that the ripe fields were full of reapers, and suddenly the air became so frightfully hot that the men dropped down in a faint. Then I called to them, "Why don't you bring out our mare, which is as tall as two days, and as broad as half a day, and make a shade for yourselves?" My father heard what I said and jumped quickly on the mare, and the reapers worked with a will in the shadow, while I snatched up a wooden pail to bring them some water to drink. When I got to the well everything was frozen hard, so in order to draw some water I had to take off my head and break the ice with it. As I drew near them, carrying the water, the reapers all cried out, "Why, what has become of your head?" I put up my hand and discovered that I really had no head, and that I must have left it in the well. I ran back to look for it, but found that meanwhile a fox which was passing by had pulled my head out of the water, and was tearing at my brains. I stole cautiously up to him, and gave him such a kick that he uttered a loud scream, and let fall a parchment on which was written, "The cake is mine, and the beardless one goes empty-handed."' With these words the boy rose, took the cake, and went home, while the beardless one remained behind to swallow his disappointment.

(Volksmarchen der Serben.)

Il più bel bugiardo del mondo

Ai margini del bosco viveva un vecchio che aveva un unico figlio; un giorno chiamò il ragazzo a sé e disse di volere un terreno coltivato a cereali, ma il giovane doveva assicurarsi di non entrare mai in nessun mulino in cui il mugnaio fosse senza barba. Il ragazzo prese i cereali e si mise in cammino; prima che fosse andato molto lontano, si trovò di fronte un grande mulino sulla cui soglia stava un mugnaio senza barba.

"Ti saluto, uomo senza barba!" gridò il ragazzo.

"Ti saluto, figliolo." rispose l'uomo.

"Potrei macinare qualcosa qui?"

"Certamente! Finirò ciò che sto facendo e poi tu potrai macinare quanto vorrai."

Improvvisamente il ragazzo si rammentò di ciò che gli aveva detto suo padre e disse addio all'uomo, scendendo lungo il fiume finché trovò un altro mulino, ignorando che, appena aveva voltato le spalle, l'uomo senza barba aveva scelto una sacca di grano ed era corso in fretta al medesimo mulino prima di lui. Quando il ragazzo ebbe raggiunto il secondo mulino e vide un secondo uomo senza barba seduto lì, non si fermò e proseguì fino al terzo mulino. Ma anche stavolta l'uomo senza barba era stato più furbo di lui e d era arrivato per primo lungo un'altra strada. Quando ciò accadde per la quarta volta, il ragazzo si arrabbiò e si disse, "Non va bene, sembra che ci sia un uomo senza barba in ogni mulino." Si mise il sacco sulle spalle e decise di macinare il proprio grano dove si trovava.

L'uomo senza barba stava finendo di macinare il proprio grano e quando ebbe fatto, disse al ragazzo, che stava cominciando a macinare il suo, "Suppongo, figliolo, che faremo una torta con il grano che hai qui."

Il ragazzo era piuttosto turbato nel ricordare le parole di suo padre, ma pensò tra sé, "Ciò che è fatto non può essere disfatto." e rispose "Bene, faremo così."

Allora l'uomo senza barba si alzò, versò la farina nel mastello, fece un buco nel mezzo, dicendo al ragazzo di raccogliere l'acqua del fiume con le mani per amalgamare la torta. Quando la torta fu pronta per essere cucinata, la mise sul fuoco e la coprì con la cenere calda finché fu cotta. Poi l'appoggiarono contro muro, perché era troppo grande per entrare in una madia, e l'uomo senza barba disse al ragazzo:

"Guarda qui, figliolo: se dividiamo la torta, nessuno di noi ne avrà a sufficienza. Vediamo chi tra noi due può raccontare la bugia più grande e chi inventerà la migliore, avrà l'intera torta."

Il ragazzo, non sapendo che altro fare, rispose: "D'accordo, comincia tu."

Così l'uomo senza barba incominciò a mentire meglio che poté e Quando fu stanco di inventare nuove bugie, il ragazzo gli disse: "Mio buon amico, se è quello tutto ciò che sai fare, non è poi molto! Ascoltami e ti narrerò una storia vera.

"In gioventù, quand'ero vecchio, avevo molti alveari. Ogni mattina quando mi alzavo, li contavo, ed era abbastanza facile contare le api, ma non avrei mai potuto calcolare correttamente il numero degli alveari. Un giorno, mentre stavo contando le api, scoprii di aver perso la migliore e, senza perdere un istante, sellai un gallo e andai a cercarla. Seguii le sue tracce fino alla spiaggia e capii che aveva attraversato il mare e che dovevo seguirla. Quando ebbi raggiunto la parte opposta, trovai un uomo che aveva aggiogato la mia ape a un aratro e con il suo aiuto stava seminando miglio.

"«Quella è la mia ape! »gridai. «Dove l'hai presa? ».

«Fratello, » replicò l'uomo, «se è tua, prendila. » e non solo mi restituì l'ape, ma in aggiunta mi diede un sacco di miglio perché aveva usato la mia ape. Allora mi misi il sacco in spalla, presi la sella dal dorso del gallo e la posi sul dorso dell'ape, sulla quale montai, conducendo il gallo con uno spago affinché potesse riposarsi. Mentre stavamo volando sul mare verso casa, una delle corde che legavano il sacco di miglio si ruppe in due, e il sacco finì dritto nell'oceano. Ne avevo perso parecchio, naturalmente, ed era inutile pensarci, e per il momento tornammo salvi prima che facesse notte. Allora scesi dall'ape e la lascia, perché doveva cenare, detti al gallo un po' di fieno e andai a dormire. Ma quando mi sveglia alla luce del sole, che scena videro i miei occhi! Durante la notte i lupi erano venuti e avevano mangiato la mia ape. Il miele giaceva alle caviglie della valle e alle ginocchia delle colline. Allora comincia a pensare al modo migliore per raccoglierne un po' e portarmelo a casa.

"Poi successe che avevo con me una piccola ascia, e ne feci uso nel bosco, sperando di incontrare qualche animale che avrei potuto uccidere e con la cui pelle farmi una borsa. Appena entrai nella foresta, vidi due caprioli che saltavano su una zampa, così li abbattei con un sol colpo e con le loro pelli mi feci tre borse che riempii tutte con il miele e collocai sul dorso del gallo. Alla fine tornai a casa, dove mi dissero che mio padre era appena nato e dovevo andare subito a procurarmi l'acqua benedetta per battezzarlo. Come me ne fui andato, rimuginai nella mia mente se se non ci fosse un modo per recuperare il miglio che era caduto in mare, e quando arrivai dove c'era l'acqua benedetta, vidi che il miglio era caduto in un terreno fertile e stava crescendo sotto i miei occhi. E per di più fu tagliato da una mano invisibile e usato per farne una torta.

"Ah, com'ero preoccupato! Così presi sia la torta che l'acqua benedetta e stavo volando verso casa sopra il mare quando cadde una forte pioggia e il mare si gonfiò e spazzò via la torta di miglio. Ah, com'ero preoccupato per la perdita quando fui di nuovo salvo sulla terraferma.

"Improvvisamente mi ricordai di avere i capelli lunghi. Se stavo in piedi, sfioravano il terreno, se invece ero seduto mi arrivavano appena alle orecchie. Afferrai un coltello e tagliai un lungo ricciolo, che intrecciai, e quando fu notte lo annodai e mi accinsi a usarlo come cuscino. Ma come potevo accendere il fuoco? Avevo la scatoletta con l'esca, ma non la legna. Allora mi venne in mente che avevo infilato un ago negli abiti, così lo presi, lo feci a pezzi e lo accesi, poi mi sdraiai accanto al fuoco per dormire. Ma la sfortuna mi perseguitava. Mentre stavo dormendo, una scintilla del fuoco mi incendiò i capelli, che bruciarono in un attimo. Disperato mi gettai per terra e immediatamente vi sprofondai fino alla vita. Lottavo per liberarmi, ma cadevo sempre più giù; così corsi a casa, afferrai una vanga, mi tirai fuori e portai a casa l'acqua benedetta. Lungo la strada notai che i campi rigogliosi erano pieni di mietitori e improvvisamente l'aria si fece così spaventosamente calda che gli uomini svennero. Allora gridai loro, «Perché non fate uscire la nostra giumenta, che è alta come due giorni e larga come mezza giornata e può farvi ombra? ». Mio padre sentì ciò che avevo detto, balzò subito sulla giumenta e i mietitori lavorarono di buona lena all'ombra, mentre io afferrai un secchio di legno per portare loro un po' d'acqua da bere. Quando andai al pozzo tutto era ghiacciato, così per avere l'acqua dovetti togliermi la testa e spezzare con essa il ghiaccio. Come tornai accanto a loro, portando l'acqua, i mietitori gridarono: «Che cosa è accaduto alla tua testa?». Sollevai la mano e scoprii che realmente non avevo la testa, dovevo averla lasciata al pozzo. Corsi indietro a cercarla, ma scoprii che nel frattempo una volpe di passaggio aveva tirato fuori dall'acqua la mia testa e stava cavando il mio cervello. Mi avvicinai furtivamente e le diedi un tale calcio che emise un terribile urlo e lasciò cadere una pergamena sulla quale era scritto: «Questa torta è mia e l'uomo senza barba se ne va a mani vuote. »"

Con queste parole il ragazzo si alzò, prese la torta e tornò a casa, mente l'uomo senza barba rimase lì a smaltire la delusione.

(Racconto popolare della Serbia)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)