The Nunda, Eater of People Nose

(MP3-21'38'')

Once upon a time there lived a sultan who loved his garden dearly, and planted it with trees and flowers and fruits from all parts of the world. He went to see them three times every day: first at seven o’clock, when he got up, then at three, and lastly at half-past five. There was no plant and no vegetable which escaped his eye, but he lingered longest of all before his one date tree.

Now the sultan had seven sons. Six of them he was proud of, for they were strong and manly, but the youngest he disliked, for he spent all his time among the women of the house. The sultan had talked to him, and he paid no heed; and he had beaten him, and he paid no heed; and he had tied him up, and he paid no heed, till at last his father grew tired of trying to make him change his ways, and let him alone.

Time passed, and one day the sultan, to his great joy, saw signs of fruit on his date tree. And he told his vizir, ‘My date tree is bearing;’ and he told the officers, ‘My date tree is bearing;’ and he told the judges, ‘My date tree is bearing;’ and he told all the rich men of the town.

He waited patiently for some days till the dates were nearly ripe, and then he called his six sons, and said: ‘One of you must watch the date tree till the dates are ripe, for if it is not watched the slaves will steal them, and I shall not have any for another year.’

And the eldest son answered, ‘I will go, father,’ and he went.

The first thing the youth did was to summon his slaves, and bid them beat drums all night under the date tree, for he feared to fall asleep. So the slaves beat the drums, and the young man danced till four o’clock, and then it grew so cold he could dance no longer, and one of the slaves said to him: ‘It is getting light; the tree is safe; lie down, master, and go to sleep.’

So he lay down and slept, and his slaves slept likewise.

A few minutes went by, and a bird flew down from a neighbouring thicket, and ate all the dates, without leaving a single one. And when the tree was stripped bare, the bird went as it had come. Soon after, one of the slaves woke up and looked for the dates, but there were no dates to see. Then he ran to the young man and shook him, saying:

‘Your father set you to watch the tree, and you have not watched, and the dates have all been eaten by a bird.’

The lad jumped up and ran to the tree to see for himself, but there was not a date anywhere. And he cried aloud, ‘What am I to say to my father? Shall I tell him that the dates have been stolen, or that a great rain fell and a great storm blew? But he will send me to gather them up and bring them to him, and there are none to bring! Shall I tell him that Bedouins drove me away, and when I returned there were no dates? And he will answer, “You had slaves, did they not fight with the Bedouins?” It is the truth that will be best, and that will I tell him.’

Then he went straight to his father, and found him sitting in his verandah with his five sons round him; and the lad bowed his head.

‘Give me the news from the garden,’ said the sultan.

And the youth answered, ‘The dates have all been eaten by some bird: there is not one left.’

The sultan was silent for a moment: then he asked, ‘Where were you when the bird came?’

The lad answered: ‘I watched the date tree till the cocks were crowing and it was getting light; then I lay down for a little, and I slept. When I woke a slave was standing over me, and he said, “There is not one date left on the tree!” And I went to the date tree, and saw it was true; and that is what I have to tell you.’

And the sultan replied, ‘A son like you is only good for eating and sleeping. I have no use for you. Go your way, and when my date tree bears again, I will send another son; perhaps he will watch better.’

So he waited many months, till the tree was covered with more dates than any tree had ever borne before. When they were near ripening he sent one of his sons to the garden: saying, ‘My son, I am longing to taste those dates: go and watch over them, for to-day’s sun will bring them to perfection.’

And the lad answered: ‘My father, I am going now, and to-morrow, when the sun has passed the hour of seven, bid a slave come and gather the dates.’

‘Good,’ said the sultan.

The youth went to the tree, and lay down and slept. And about midnight he arose to look at the tree, and the dates were all there—beautiful dates, swinging in bunches.

‘Ah, my father will have a feast, indeed,’ thought he. ‘What a fool my brother was not to take more heed! Now he is in disgrace, and we know him no more. Well, I will watch till the bird comes. I should like to see what manner of bird it is.’

And he sat and read till the cocks crew and it grew light, and the dates were still on the tree.

‘Oh my father will have his dates; they are all safe now,’ he thought to himself. ‘I will make myself comfortable against this tree,’ and he leaned against the trunk, and sleep came on him, and the bird flew down and ate all the dates.

When the sun rose, the head-man came and looked for the dates, and there were no dates. And he woke the young man, and said to him, ‘Look at the tree.’

And the young man looked, and there were no dates. And his ears were stopped, and his legs trembled, and his tongue grew heavy at the thought of the sultan. His slave became frightened as he looked at him, and asked, ‘My master, what is it?’

He answered, ‘I have no pain anywhere, but I am ill everywhere. My whole body is well, and my whole body is sick I fear my father, for did I not say to him, “To-morrow at seven you shall taste the dates”? And he will drive me away, as he drove away my brother! I will go away myself, before he sends me.’

Then he got up and took a road that led straight past the palace, but he had not walked many steps before he met a man carrying a large silver dish, covered with a white cloth to cover the dates.

And the young man said, ‘The dates are not ripe yet; you must return to-morrow.’

And the slave went with him to the palace, where the sultan was sitting with his four sons.

‘Good greeting, master!’ said the youth.

And the sultan answered, ‘Have you seen the man I sent?’

‘I have, master; but the dates are not yet ripe.’

But the sultan did not believe his words, and said; ‘This second year I have eaten no dates, because of my sons. Go your ways, you are my son no longer!’

And the sultan looked at the four sons that were left him, and promised rich gifts to whichever of them would bring him the dates from the tree. But year by year passed, and he never got them. One son tried to keep himself awake with playing cards; another mounted a horse and rode round and round the tree, while the two others, whom their father as a last hope sent together, lit bonfires. But whatever they did, the result was always the same. Towards dawn they fell asleep, and the bird ate the dates on the tree.

The sixth year had come, and the dates on the tree were thicker than ever. And the head-man went to the palace and told the sultan what he had seen. But the sultan only shook his head, and said sadly, ‘What is that to me? I have had seven sons, yet for five years a bird has devoured my dates; and this year it will be the same as ever.’

Now the youngest son was sitting in the kitchen, as was his custom, when he heard his father say those words. And he rose up, and went to his father, and knelt before him. ‘Father, this year you shall eat dates,’ cried he. ‘And on the tree are five great bunches, and each bunch I will give to a separate nation, for the nations in the town are five. This time, I will watch the date tree myself.’ But his father and his mother laughed heartily, and thought his words idle talk.

One day, news was brought to the sultan that the dates were ripe, and he ordered one of his men to go and watch the tree. His son, who happened to be standing by, heard the order, and he said:

‘How is it that you have bidden a man to watch the tree, when I, your son, am left?’

And his father answered, ‘Ah, six were of no use, and where they failed, will you succeed?’

But the boy replied: ‘Have patience to-day, and let me go, and to-morrow you shall see whether I bring you dates or not.’

‘Let the child go, Master,’ said his wife; ‘perhaps we shall eat the dates—or perhaps we shall not—but let him go.’

And the sultan answered: ‘I do not refuse to let him go, but my heart distrusts him. His brothers all promised fair, and what did they do?’

But the boy entreated, saying, ‘Father, if you and I and mother be alive to-morrow, you shall eat the dates.’

‘Go then,’ said his father.

When the boy reached the garden, he told the slaves to leave him, and to return home themselves and sleep. When he was alone, he laid himself down and slept fast till one o’clock, when he arose, and sat opposite the date tree. Then he took some Indian corn out of one fold of his dress, and some sandy grit out of another.

And he chewed the corn till he felt he was growing sleepy, and then he put some grit into his mouth, and that kept him awake till the bird came.

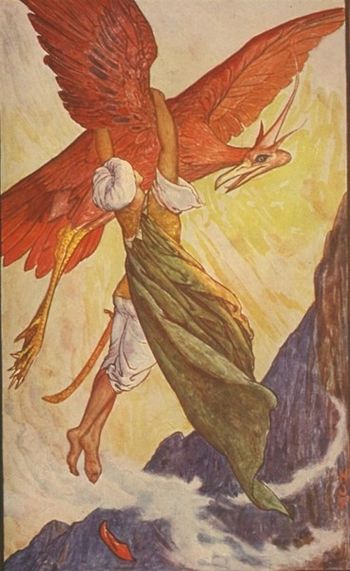

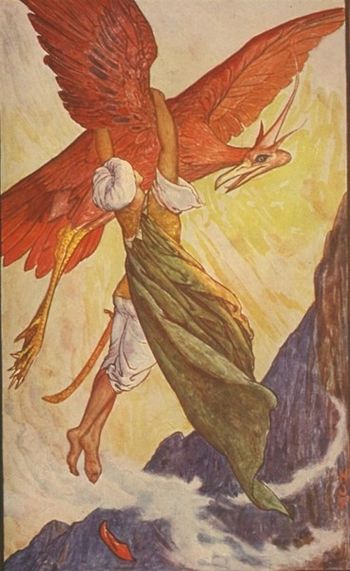

stole upIt looked about at first without seeing him, and whispering to itself, ‘There is no one here,’ fluttered lightly on to the tree and stretched out his beak for the dates. Then the boy stole softly up, and caught it by the wing.

The bird turned and flew quickly away, but the boy never let go, not even when they soared high into the air.

‘Son of Adam,’ the bird said when the tops of the mountains looked small below them, ‘if you fall, you will be dead long before you reach the ground, so go your way, and let me go mine.’

But the boy answered, ‘Wherever you go, I will go with you. You cannot get rid of me.’

‘I did not eat your dates,’ persisted the bird, ‘and the day is dawning. Leave me to go my way.’

But again the boy answered him: ‘My six brothers are hateful to my father because you came and stole the dates, and to-day my father shall see you, and my brothers shall see you, and all the people of the town, great and small, shall see you. And my father’s heart will rejoice.’

‘Well, if you will not leave me, I will throw you off,’ said the bird.

So it flew up higher still—so high that the earth shone like one of the other stars.

‘How much of you will be left if you fall from here?’ asked the bird.

‘If I die, I die,’ said the boy, ‘but I will not leave you.’

And the bird saw it was no use talking, and went down to the earth again.

‘Here you are at home, so let me go my way,’ it begged once more; ‘or at least make a covenant with me.’

‘What covenant?’ said the boy.

‘Save me from the sun,’ replied the bird, ‘and I will save you from rain.’

‘How can you do that, and how can I tell if I can trust you?’

‘Pull a feather from my tail, and put it in the fire, and if you want me I will come to you, wherever I am.’

And the boy answered, ‘Well, I agree; go your way.’

‘Farewell, my friend. When you call me, if it is from the depths of the sea, I will come.’

The lad watched the bird out of sight; then he went straight to the date tree. And when he saw the dates his heart was glad, and his body felt stronger and his eyes brighter than before. And he laughed out loud with joy, and said to himself, ‘This is MY luck, mine, Sit-in-the-kitchen! Farewell, date tree, I am going to lie down. What ate you will eat you no more.’

The sun was high in the sky before the head-man, whose business it was, came to look at the date tree, expecting to find it stripped of all its fruit, but when he saw the dates so thick that they almost hid the leaves he ran back to his house, and beat a big drum till everybody came running, and even the little children wanted to know what had happened.

‘What is it? What is it, head-man?’ cried they.

‘Ah, it is not a son that the master has, but a lion! This day Sit-in-the-kitchen has uncovered his face before his father!’

‘But how, head-man?’

‘To day the people may eat the dates.’

‘Is it true, head-man?’

‘Oh yes, it is true, but let him sleep till each man has brought forth a present. He who has fowls, let him take fowls; he who has a goat, let him take a goat; he who has rice, let him take rice.’ And the people did as he had said.

Then they took the drum, and went to the tree where the boy lay sleeping.

And they picked him up, and carried him away, with horns and clarionets and drums, with clappings of hands and shrieks of joy, straight to his father’s house.

When his father heard the noise and saw the baskets made of green leaves, brimming over with dates, and his son borne high on the necks of slaves, his heart leaped, and he said to himself ‘To-day at last I shall eat dates.’ And he called his wife to see what her son had done, and ordered his soldiers to take the boy and bring him to his father.

‘What news, my son?’ said he. ‘News? I have no news, except that if you will open your mouth you shall see what dates taste like.’ And he plucked a date, and put it into his father’s mouth.

‘Ah! You are indeed my son,’ cried the sultan. ‘You do not take after those fools, those good-for-nothings. But, tell me, what did you do with the bird, for it was you, and you only who watched for it?’

‘Yes, it was I who watched for it and who saw it. And it will not come again, neither for its life, nor for your life, nor for the lives of your children.’

‘Oh, once I had six sons, and now I have only one. It is you, whom I called a fool, who have given me the dates: as for the others, I want none of them.’

But his wife rose up and went to him, and said, ‘Master, do not, I pray you, reject them,’ and she entreated long, till the sultan granted her prayer, for she loved the six elder ones more than her last one.

So they all lived quietly at home, till the sultan’s cat went and caught a calf. And the owner of the calf went and told the sultan, but he answered, ‘The cat is mine, and the calf mine,’ and the man dared not complain further.

Two days after, the cat caught a cow, and the sultan was told, ‘Master, the cat has caught a cow,’ but he only said, ‘It was my cow and my cat.’

And the cat waited a few days, and then it caught a donkey, and they told the sultan, ‘Master, the cat has caught a donkey,’ and he said, ‘My cat and my donkey.’ Next it was a horse, and after that a camel, and when the sultan was told he said, ‘You don’t like this cat, and want me to kill it. And I shall not kill it. Let it eat the camel: let it even eat a man.’

And it waited till the next day, and caught some one’s child. And the sultan was told, ‘The cat has caught a child.’ And he said, ‘The cat is mine and the child mine.’ Then it caught a grown-up man.

After that the cat left the town and took up its abode in a thicket near the road. So if any one passed, going for water, it devoured him. If it saw a cow going to feed, it devoured him. If it saw a goat, it devoured him. Whatever went along that road the cat caught and ate.

Then the people went to the sultan in a body, and told him of all the misdeeds of that cat. But he answered as before, ‘The cat is mine and the people are mine.’ And no man dared kill the cat, which grew bolder and bolder, and at last came into the town to look for its prey.

One day, the sultan said to his six sons, ‘I am going into the country, to see how the wheat is growing, and you shall come with me.’ They went on merrily along the road, till they came to a thicket, when out sprang the cat, and killed three of the sons.

‘The cat! The cat!’ shrieked the soldiers who were with him. And this time the sultan said:

‘Seek for it and kill it. It is no longer a cat, but a demon!’

And the soldiers answered him, ‘Did we not tell you, master, what the cat was doing, and did you not say, “My cat and my people”?’

And he answered: ‘True, I said it.’

Now the youngest son had not gone with the rest, but had stayed at home with his mother; and when he heard that his brothers had been killed by the cat he said, ‘Let me go, that it may slay me also.’ His mother entreated him not to leave her, but he would not listen, and he took his sword and a spear and some rice cakes, and went after the cat, which by this time had run of to a great distance.

The lad spent many days hunting the cat, which now bore the name of ‘The Nunda, eater of people,’ but though he killed many wild animals he saw no trace of the enemy he was hunting for. There was no beast, however fierce, that he was afraid of, till at last his father and mother begged him to give up the chase after the Nunda.

But he answered: ‘What I have said, I cannot take back. If I am to die, then I die, but every day I must go and seek for the Nunda.’

And again his father offered him what he would, even the crown itself, but the boy would hear nothing, and went on his way.

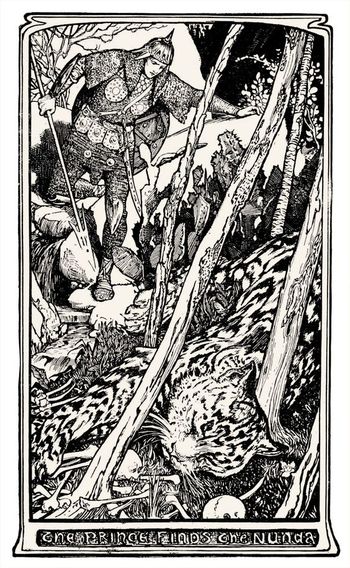

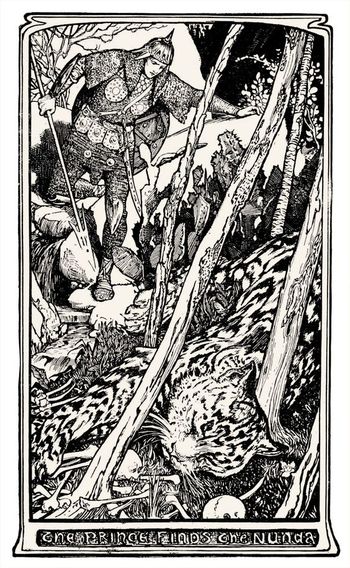

Many times his slaves came and told him, ‘We have seen footprints, and to-day we shall behold the Nunda.’ But the footprints never turned out to be those of the Nunda. They wandered far through deserts and through forests, and at length came to the foot of a great hill. And something in the boy’s soul whispered that here was the end of all their seeking, and to-day they would find the Nunda.

But before they began to climb the mountain the boy ordered his slaves to cook some rice, and they rubbed the stick to make a fire, and when the fire was kindled they cooked the rice and ate it. Then they began their climb.

Suddenly, when they had almost reached the top, a slave who was on in front cried:

‘Master! Master!’ And the boy pushed on to where the slave stood, and the slave said:

‘Cast your eyes down to the foot of the mountain.’ And the boy looked, and his soul told him it was the Nunda.

And he crept down with his spear in his hand, and then he stopped and gazed below him.

‘This MUST be the real Nunda,’ thought he. ‘My mother told me its ears were small, and this one’s are small. She told me it was broad and not long, and this is broad and not long. She told me it had spots like a civet-cat, and this has spots like a civet-cat.’

Then he left the Nunda lying asleep at the foot of the mountain, and went back to his slaves.

‘We will feast to-day,’ he said; ‘make cakes of batter, and bring water,’ and they ate and drank. And when they had finished he bade them hide the rest of the food in the thicket, that if they slew the Nunda they might return and eat and sleep before going back to the town. And the slaves did as he bade them.

It was now afternoon, and the lad said: ‘It is time we went after the Nunda.’ And they went till they reached the bottom and came to a great forest which lay between them and the Nunda.

Here the lad stopped, and ordered every slave that wore two cloths to cast one away and tuck up the other between his legs. ‘For,’ said he, ‘the wood is not a little one. Perhaps we may be caught by the thorns, or perhaps we may have to run before the Nunda, and the cloth might bind our legs, and cause us to fall before it.’

And they answered, ‘Good, master,’ and did as he bade them. Then they crawled on their hands and knees to where the Nunda lay asleep.

Noiselessly they crept along till they were quite close to it; then, at a sign from the boy, they threw their spears. The Nunda did not stir: the spears had done their work, but a great fear seized them all, and they ran away and climbed the mountain.

The sun was setting when they reached the top, and glad they were to take out the fruit and the cakes and the water which they had hidden away, and sit down and rest themselves. And after they had eaten and were filled, they lay down and slept till morning.

When the dawn broke they rose up and cooked more rice, and drank more water. After that they walked all round the back of the mountain to the place where they had left the Nunda, and they saw it stretched out where they had found it, stiff and dead. And they took it up and carried it back to the town, singing as they went, ‘He has killed the Nunda, the eater of people.’

And when his father heard the news, and that his son was come, and was bringing the Nunda with him, he felt that the man did not dwell on the earth whose joy was greater than his. And the people bowed down to the boy and gave him presents, and loved him, because he had delivered them from the bondage of fear, and had slain the Nunda.

Adapted from Swahili Tales.

Il Nunda, mangiatore di uomini

C’era una volta un sultano che amava teneramente il proprio giardino e vi piantava alberi e fiori e frutti di ogni parte del mondo. Andava a visitarlo tre volte il giorno: la prima alle sette in punto, quando si alzava, poi alle quindici e infine alle diciassette e trenta. Non c’era pianta o vegetale che sfuggisse ai suoi occhi, ma lui si tratteneva più a lungo davanti all’albero di datteri.

Dovete sapere che il sultano aveva sette figli. Era orgoglioso di sei di loro perché erano robusti e virili, ma disprezzava il più giovane perché trascorreva il tempo tra le donne della casa. Il sultano gli aveva parlato, ma lui non se ne curava; lo aveva picchiato, ma lui non se ne curava; lo aveva legato, ma lui non se ne curava finché infine il padre si stancò di cercare di cambiarlo e lo lasciò perdere.

Il tempo passava e un giorno il sultano, con grande gioia, vide i primi frutti sull’albero di datteri. Disse al visir: “Il mio albero di datteri sta dando i frutti.” e disse agli ufficiali: “Il mio albero di datteri sta dando i frutti.” e disse ai giudici: “Il mio albero di datteri sta dando i frutti.” e lo disse a tutti i benestanti della città.

Attese pazientemente per alcuni giorni che i datteri fossero quasi maturi e poi chiamò i sei figli e disse: “Uno di voi deve fare la guardia all’albero di datteri finché i frutti saranno maturi perché se non sarà sorvegliato, gli schiavi li ruberanno e io non avrò niente per un altro anno.”

Il figlio maggiore rispose: “Padre, andrò io.” e così fece.

La prima cosa che il giovane fece fu convocare i propri schiavi e dire loro di battere i tamburi per tutta la notte sotto l’albero perché temeva di addormentarsi. Così gli schiavi batterono i tamburi e il giovane danzò fino alle quattro del mattino, poi ebbe così freddo e non poté danzare più oltre tanto che uno degli schiavi gli disse: “Si sta facendo giorno, l’albero è salvo; sdraiatevi, padrone, e mettevi a dormire.”

Così si sdraiò e dormi, e i suoi schiavi fecero altrettanto.

Erano trascorsi pochi minuti che un uccello planò da un boschetto vicino e mangiò tutti i datteri senza lasciarne nemmeno uno. Quando l’albero fu spogliato, l’uccello se ne andò come era venuto. Più tardi uno degli schiavi si svegliò e guardò i datteri, ma non ne vide nessuno. Allora corse dal giovane e lo scosse, dicendo:

“Vostro padre vi ha mandato a sorvegliare l’albero e voi non l’avete fatto; i datteri sono stati mangiati tutti da un uccello.”

Il giovane balzò in piedi e corse all’albero per vedere con i propri occhi, ma non c’era un solo dattero da nessuna parte. E allora gridò: “Che cosa dirò a mio padre? Gli dirò che i datteri sono stati rubati o che è caduta un’intensa pioggia e ha soffiato una forte tempesta? Mi manderà a raccoglierli per portaglieli, e non ce ne sarà nessuno! Gli dirò che i beduini mi hanno portato via e che quando sono tornato non c’era un solo dattero? E lui domanderà ‘Avevi degli schiavi, non hanno lottato con i beduini?’ Sarà meglio dire la verità e quella gli dirò.”

Allora andò difilato dal padre e lo trovò seduto nella veranda con i cinque figli attorno; il ragazzo chinò la testa.

“Dammi notizie del giardino.” disse il sultano.

Il giovane rispose: “I datteri sono stati mangiati tutti da un uccello, non ne è rimasto nemmeno uno.”

Il sultano rimase in silenzio per un istante poi chiese: “Dov’eri quando è venuto l’uccello?”

Il ragazzo rispose: “Ho sorvegliato l’albero finché il gallo ha cantato e si è fatto giorno, poi mi sono sdraiato un po’ e ho dormito. Quando mi sono svegliato uno schiavo era chino su di me e diceva: ‘Non c’è un solo dattero sull’albero!’ io sono andato all’albero di datteri e ho visto che era vero e questo è quanto ti devo dire.”

Il sultano replicò: “Un figlio come te è buono solo per mangiare e dormire. Non mi servi. Vattene, e quando il mio albero di datteri farà di nuovo i frutti, manderò un altro figlio e forse lui sorveglierà meglio.”

Così attese per molti mesi finché l’albero fu di nuovo coperto di tanti datteri come nessun albero aveva mai prodotto prima. Quando stavano per maturare, mandò in giardino uno dei figli, dicendo: “Figlio mio, desidero gustare quei datteri: va’ e sorvegliali perché oggi il sole li renderà perfetti.”

Il ragazzo rispose:” Padre, adesso vado e domani dopo le sette ordina a uno schiavo di andare a raccogliere i datteri.”

“Bene.” disse il sultano.

Il giovane andò presso l’albero, si sdraiò e dormì. Verso mezzanotte si alzò a controllare l’albero e tutti i datteri erano là, splendidi, che oscillavano sui rami.

‘Mio padre farà senz’altro una festa.’ pensò ‘Che sciocco è stato mio fratello a non fare più attenzione! Adesso è in disgrazia e non sappiamo nulla di lui. Farò la guardia finché verrà l’uccello. Mi piacerebbe vedere che razzo di uccello sia.’

E sedette a leggere finché il gallo cantò e si fece giorno, e i datteri erano ancora sull’albero.

‘Mio padre avrà i suoi datteri. Adesso sono salvi ’pensò ‘Mi sistemerò più comodamente contro l’albero.’ Si appoggiò al tronco, si addormentò e l’uccello scese a mangiare tutti i datteri.

Quando il sole si levò, il sorvegliante venne a vedere i datteri e non ce n’erano. Svegliò il giovane e gli disse: “Guarda l’albero.”

Il giovane guardò e non c’erano datteri. Le orecchie gli si otturarono, le gambe gli tremarono e la lingua gli diventò pesante al pensiero del sultano. Lo schiavo si spaventò nel vederlo e chiese: “Padrone, che succede?”

Il ragazzo rispose: “Non ho nessun dolore da nessuna parte, ma sto male. Tutto il mio corpo sta bene e male al tempo stesso per paura di mio padre; non gli ho forse detto ‘Domani alle sette gusterai i datteri’? mi caccerà come ha fatto con mio fratello! Me ne vado da solo, prima che mi mandi via.”

Allora si alzò e prese una strada che oltrepassava il palazzo, ma aveva fatto solo pochi passi prima di incontrare un uomo che trasportava un grande piatto d’argento, coperto con un panno bianco per riparare i datteri.

Il giovane disse: “I datteri non sono ancora maturi, devi tornare domani.”

E lo schiavo andò con lui a palazzo, dove il sultano era seduto con i quattro figli.

“Salute a voi, signore!” disse il giovane.

E il sultano chiese: “Hai visto l’uomo che ho mandato?”

“L’ho visto, signore, ma i datteri non sono ancora maturi.”

Il sultano non credette a queste parole e disse: “Questo è il secondo anno in cui non mangio datteri a causa dei miei figli. Vattene, non sei più mio figlio.”

Il sultano guardò i quattro figli che gli erano rimasti e promise ricchi doni a chiunque di loro gli avesse portato i datteri di quell’albero. Ma passò un anno dopo l’altro e non li ebbe mai. Un figlio aveva tentato di restare sveglio giocando a carte; un altro montando a cavallo e galoppando intorno all’albero mentre gli altri due, che il padre aveva mandato insieme come ultima possibilità, avevano acceso un falò. Ma qualsiasi cosa avessero fatto, il risultato era stato sempre il medesimo. All’alba si erano addormentati e l’uccello aveva mangiato i datteri dell’albero.

Era trascorso il sesto anno e i datteri sull’albero erano più abbondanti che mai. Allora il sorvegliante andò a palazzo e disse al sultano ciò che aveva visto. Il sultano si limitò a scuotere la testa e disse tristemente: “Che me ne importa? Avevo mandato sei figli, ma per cinque anni l’uccello ha divorato i miei datteri e quest’anno sarà come tutti gli altri.”

Il figlio più giovane era seduto in cucina, come suo solito, quando sentì il padre pronunciare queste parole. Allora si alzò e andò da lui e gli si inginocchiò davanti. “Padre, quest’anno mangerete i datteri!” esclamò “Sull’albero ci sono cinque grossi rami e darò ogni ramo a una diversa tribù perché in città ce ne sono cinque. Stavolta sorveglierò io stesso l’albero di datteri.” Ma il padre e la madre risero di cuore e pensarono che le sue parole fossero solo chiacchiere.

Un giorno fu data notizia al sultano che i datteri erano maturi e lui ordinò a uno dei suoi uomini di andare a sorvegliare l’albero. Il figlio, che si trovava nei paraggi, sentì l’ordine e disse:

“Come mai avete detto a quell’uomo di sorvegliare l’albero quando io, vostro figlio, ci sto andando?”

Il padre rispose: “Sei non ne sono stati capaci e perché dovresti riuscire tu dove loro hanno fallito?”

Il ragazzo rispose: “Abbiate pazienza oggi e lasciatemi andare, domani vedrete se vi porterò i datteri o no.”

“Lascia che il ragazzo vada, mio signore,” disse la moglie “forse mangeremo i datteri o forse no, ma lascialo andare.”

Il sultano rispose: “Non glielo nego, ma il mio cuore dubita di lui. Tutti i suoi fratelli promettevano bene e che cosa hanno fatto?”

Il ragazzo supplicò, dicendo: “Padre, se voi, io e madre saremo vivi domani, voi mangerete i datteri.”

“Allora vai.” disse il padre.

Quando il ragazzo fu giunto in giardino, disse agli schiavi di lasciarlo e di tornare a casa a dormire. Quando fu solo, si sdraiò e dormì fino all’una in punto quando si alzò e sedette di fronte all’albero. Allora tirò fuori da una tasca dell’abito un po’ di grano indiano e dall’altra granelli di sabbia.

Masticò il grano finché sentì di avere sonno e poi si mise in bocca un po’ di sabbia e ciò lo tenne sveglio fino all’arrivo dell’uccello.

Dapprima si guardò attorno senza vedere il ragazzo e, sussurrando tra sé: ‘Qui non c’è nessuno.’, planò delicatamente sull’albero e allungò il becco per prendere i datteri. Allora il ragazzo si avvicinò furtivamente e lo afferrò per un’ala.

L’uccello si volse e volò via in fretta, ma il ragazzo non lo lasciò andare, neppure quando salirono vertiginosamente in aria.

“Figlio di Adamo,” disse l’uccello quando le cime delle montagne sembrarono piccole sotto di loro “se cadrai, morirai prima di raggiungere il suolo; vai per la tua strada e lasciami andare per la mia.”

Il ragazzo rispose: “Dovunque tu vada, io verrò con te. Non puoi liberarti di me.”

“Non ho mangiato i tuoi datteri,” insistette l’uccello “e si sta facendo giorno. Lasciami andare per la mia strada.”

Di nuovo il ragazzo gli rispose: “I miei sei fratelli sono odiosi a mio padre perché tu sei venuto e hai rubato i datteri e oggi mio padre ti vedrà, e i miei fratelli ti vedranno, e tutta gli abitanti della città, grandi e piccoli, ti vedranno. Il cuore di mio padre si rallegrerà.”

“E va bene, se non mi lascerai andare, ti getterò giù.” disse l’uccello.

Così volò ancora più in alto, così in alto che la terra brillò come una delle altre stelle.

“Che cosa rimarrà di te se cadrai da qui?” chiese l’uccello.

“Se devo morire, morirò,” disse il ragazzo “ma non ti lascerò andare.”

L’uccello vide che era inutile parlare e tornò giù sulla terra.

“Eccoti a casa, adesso lasciami andare per la mia strada” lo pregò ancora una volta l’uccello “oppure fai un patto con me.”

“Che patto?” chiese il ragazzo.

“Salvami dal sole e io ti salverò dalla pioggia.” rispose l’uccello.

“Come sarà possibile? E come farò a sapere se potrò fidarmi di te?”

“Strappa una piuma dalla mia coda e gettala nel fuoco e se mi vorrai, io verrò da te, ovunque sia.”

“D’accordo, accetto; vai per la tua strada.”

“Arrivederci, amico mio. Quando mi chiamerai, fosse pure dalle profondità del mare, verrò.”

Il ragazzo guardò sparire l’uccello poi andò all’albero di datteri. Quando vide i datteri, il suo cuore fu contento, il suo corpo si sentì più forte e i suoi occhi divennero più brillanti di prima. Rise forte di gioia e si disse: ‘Questa è la MIA fortuna, la mia, Seduto-in-cucina! Addio, albero di datteri, sto andando a sdraiarmi. Chi ti mangiava, non ti mangerà più.’

Il sole fu alto in cielo prima che il sorvegliante, il cui compito era quello, andasse a vedere l’albero di datteri, aspettandosi che fosse stato privato di tutti i suoi frutti, ma quando vide i datteri così fitti che quasi piegavano i rami, corse a casa e batté forte il tamburo finché tutti vennero di corsa, persino i bambini che volevano sapere che cosa fosse accaduto.

“Che c’è? Che c’è, sorvegliante?” gridarono tutti.

“Il padrone non ha un figlio, ma un leone! Oggi Seduto-in-cucina ha mostrato il suo vero volto davanti al padre!”

“E come, sorvegliante?”

“Oggi la gente potrò mangiare i datteri.”

“È vero, sorvegliante?”

“Certo che è vero! Ma lasciatelo dormire finché ogni uomo gli abbia portato un dono. Chi ha pollame, gli porti pollame; chi ha una capra, gli porti una capra; chi ha riso, gli porti il riso.” E la gente fece come lui diceva.

Poi presero il tamburo e andarono all’albero presso cui il ragazzo giaceva addormentato.

Lo presero e lo portarono via con corni e clarinetti e tamburi, con applausi e grida di gioia, fino alla casa di suo padre.

Quando il padre sentì il rumore e vide i canestri fatti di foglie verdi che traboccavano di datteri e suo figlio portato in trionfo sulle spalle degli schiavi, il cuore gli sobbalzò e si disse: ‘Oggi infine mangerò i datteri.’ E chiamò la moglie a vedere ciò che il figlio aveva fatto e ordinò ai soldati di prendere il ragazzo e di condurlo da lui.

“Che notizie, figlio mio?” disse il sultano.

“Notizie? Non ho notizie eccetto che se aprirete la bocca, potrete sapere che gusto hanno questi datteri.” E prese un dattero e lo mise in bocca al padre.

“Sei davvero mio figlio!” esclamò il sultano. “Non assomigli a quegli insensati, a quei buoni a nulla. Dimmi, che cosa hai fatto con l’uccello, perché sei stato tu, e solo tu, che hai fatto la guardia?”

“Sì, sono io che ho fatto la guardia e l’ho visto. E non tornerà di nuovo, né per la sua vita, né per la vostra, né per quella dei vostri figli.”

“Una volta avevo sei figli e adesso ne ho uno solo. Sei tu, che chiamavo sciocco, che mi hai portato i datteri: se fosse stato per gli altri, non ne avrei nessuno.”

Ma sua moglie si alzò e andò da lui, dicendo: “Mio signore, ti prego, non ripudiarli.” E lo supplicò tanto che alla fine il sultano accolse la sua preghiera perché lei amava i sei figli maggiori più di quell’ultimo.

Così vissero tutti tranquillamente a casa finché il gatto del sultano prese un vitello. Il proprietario del vitello andò dal sultano e glielo disse, ma lui rispose: “Il gatto è mio e il vitello è mio.” E l’uomo non osò lamentarsi ulteriormente.

Due giorni dopo il gatto prese una mucca e fu riferito al sultano: “Padrone, il gatto ha preso una mucca.” Ma lui disse solo: “La mucca e il gatto sono miei.”

Il gatto aspettò qualche giorno e poi prese una scimmia e dissero al sultano: “Padrone, il gatto ha preso una scimmia.” E lui rispose: “Mio è il gatto e mia la scimmia.” La volta dopo toccò a un cavallo, poi a un cammello e quando fu detto al sultano, rispose: “Non vi piace questo gatto e volete che lo uccida. Non lo ucciderò. Lasciategli mangiare il cammello, lasciategli mangiare persino un uomo.”

Il gatto attese fino al giorno successive e poi prese il figlio di qualcuno. Fu detto al sultano: “Il gatto ha preso un bambino.” E lui rispose: “Il gatto è mio e il bambino è mio.” Poi il gatto prese un adulto.

Dopodiché il gatto lasciò la città e si stabilì in un boschetto vicino alla strada. Così se qualcuno passava per andare a prendere l’acqua, lo divorava. Se vedeva una mucca che pascolava, la divorava. Se vedeva una capra, la divorava. Qualsiasi cosa passasse sulla strada, il gatto la prendeva e la mangiava.

Allora i sudditi andarono in massa dal sultano e gli raccontarono tutti i misfatti del gatto, ma lui rispose come già aveva fatto prima: “Il gatto è mio e le persone sono mie.” E nessuno osava uccidere il gatto, che diventava sempre più audace e veniva in città a cercare le prede.

Un giorno il sultano disse ai sei figli; “Sto andando per il paese a controllare quanto è cresciuto il grano e voi verrete con me.” Camminarono allegramente lungo la strada finché giunsero presso un boschetto dal quale balzò il gatto che gli uccise tre figli.

“Il gatto! Il gatto!” gridarono i soldati che erano con il sultano. E stavolta egli disse:

“Cercatelo e uccidetelo, non è più un gatto, ma un demonio!”

Allora i soldati gli chiesero: “Padrone, non vi avevamo detto ciò che stava facendo il gatto e voi non avete risposto: ‘Il gatto è mio e la gente è mia?’”

Il sultano rispose: “È vero, l’ho detto.”

Il figlio più giovane non era andato via col gruppo, ma era rimasto a casa con la madre e quando sentì che i fratelli erano stati uccisi dal gatto, disse: “Lasciatemi andare, che uccida anche me.” La madre lo supplicò di non lasciarla, ma lui non volle ascoltare; prese la spada, una lancia, un po’ di torta di riso e inseguì il gatto, che nel frattempo era corso via a gran distanza.

Il ragazzo impiegò giorni nella caccia del gatto, che adesso era chiamato con il nome di ‘Il Nunda, mangiatore di uomini’, ma sebbene avesse ucciso molti animali selvatici, non vedeva traccia del nemico che stava cacciando. Non c’erano belve, per quanto feroci, che lo spaventassero e alla fine il padre e la madre lo pregarono di abbandonare l’inseguimento del Nunda.

Ma lui rispose: “Non posso rimangiarmi ciò che ho promesso. Se dovrò morire, allora morirò, ma devo andare ogni giorno in cerca del Nunda.”

Il padre gli offrì tutto ciò che potesse volere, persino la corona, ma il ragazzo non volle sentir ragioni e proseguì per la propria strada.

Molte volte lo schiavo era venuto a dirgli: “Abbiamo visto impronte e oggi vedremo il Nunda.” Ma le impronte non portavano mai al Nunda. Vagarono per il deserto e per le foreste e infine giunsero ai piedi di una grande collina. Qualcosa nell’animo del ragazzo gli diceva che fossero giunti alla fine della ricerca e che quel giorno avrebbero trovato il Nunda.

Prima che cominciassero ad arrampicarsi sulla montagna, il ragazzo ordinò agli schiavi di cuocere un po’ di riso; radunarono ramoscelli per accendere il fuoco e quando il fuoco fu gagliardo, cucinarono il riso e lo mangiarono. Poi cominciarono l’arrampicata.

Improvvisamente, quando avevano quasi raggiunto la cima, uno schiavo che era davanti gridò:

“Padrone! Padrone!” e il ragazzo balzò avanti dove si trovava lo schiavo, che gli disse:

“Getta lo sguardo ai piedi della montagna.” Il ragazzo guardò e un presentimento gli disse che c’era il Nunda.

Sgattaiolò in basso con la lancia in mano e poi si fermò e guardò fisso sotto di sé.

‘Questo DEVE essere davvero il Nunda’ pensò. ‘Mia madre mi ha detto che ha le orecchie piccole e questo animale le ha piccole. Mi ha detto che è largo e non troppo lungo, e questo animale è largo e non troppo lungo. Mi ha detto che ha le macchie come uno zibetto e questo animale ha le macchie come uno zibetto.’

Allora lasciò il Nunda che giaceva addormentato ai piedi della montagna e tornò dagli schiavi.

“Oggi festeggeremo,” disse “fate frittelle e portate l’acqua.” e mangiarono e bevvero. Quando ebbero finito, disse loro di nascondere la rimanenza del cibo nel boschetto che, se avessero ucciso il Nunda sarebbero tornati a mangiare, a bere e a dormire prima di rientrare in città. E gli schiavi fecero ciò che aveva detto.

Si era fatto mezzogiorno e il ragazzo disse: “È tempo di andare a cercare il Nunda.” E camminarono finché raggiunsero i piedi della montagna ed entrarono nella grande foresta che si stendeva tra di loro e il Nunda.

Qui il ragazzo si fermò e ordinò a ogni schiavo che indossava due indumenti di gettarne via uno e di rimboccarsi l’altro sulle gambe. “Perché il bosco non è piccolo” disse “e forse potremmo essere punti dalle spine o dovremmo poter correre davanti al Nunda e gli indumenti a penzoloni sulle gambe potrebbero farci cadere davanti a lui.”

E loro risposero “Bene, padrone.” E fece come aveva detto loro poi avanzarono sulle mani e sulle ginocchia fino al luogo in cui in Nunda giaceva addormentato.

Scivolarono silenziosamente fino ad andargli vicino; poi, a un segnale del ragazzo, scagliarono le lance. Il Nunda non si mosse: le lance avevano svolto il loro lavoro, ma furono tutti travolti da grande paura e corsero ad arrampicarsi sulla montagna.

Il sole stava tramontando quando raggiunsero la cima e furono contenti di trovare la frutta, le frittelle e l’acqua che avevano nascosto; sedettero e si riposarono. Dopo che ebbero mangiato e si furono saziati, si sdraiarono e dormirono fino al mattino.

All’alba si alzarono e cucinarono altro riso e bevvero altra acqua. Dopo camminarono tutt’attorno al dorso della montagna fino al posto in cui avevano lasciato il Nunda e lo videro allungato dove l’avevano trovato, morto e stecchito. Lo sollevarono e lo portarono in città, cantando mentre procedevano “Egli ha ucciso il Nunda, il mangiatore di uomini.”

Quando il padre sentì la notizia, cioè che suo figlio stava tornando e stava portando con sé il Nunda, sentì che nessun uomo sulla terra avrebbe potuto provare una gioia più grande della propria. La gente si inchinò al ragazzo e gli offrì doni, lo amavano perché li aveva liberati dalla schiavitù della paura e aveva ucciso il Nunda.

Adattamento dalle fiabe Swahili.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)